Submitted in Requirement for the Degree of Master of Arts by G.E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federation Teacher Notes

Government of Western Australia Department of the Premier and Cabinet Constitutional Centre of WA Federation Teacher Notes Overview The “Federation” program is designed specifically for Year 6 students. Its aim is to enhance students’ understanding of how Australia moved from having six separate colonies to become a nation. In an interactive format students complete a series of activities that include: Discussing what Australia was like before 1901 Constructing a timeline of the path to Federation Identifying some of the founding fathers of Federation Examining some of the federation concerns of the colonies Analysing the referendum results Objectives Students will: Discover what life was like in Australia before 1901 Explain what Federation means Find out who were our founding fathers Compare and contrast some of the colony’s concerns about Federation Interpret the results of the 1899 and 1900 referendums Western Australian Curriculum links Curriculum Code Knowledge & Understandings Year 6 Humanities and Social Sciences (HASS) ACHASSK134 Australia as a Nation Key figures (e.g. Henry Parkes, Edmund Barton, George Reid, John Quick), ideas and events (e.g. the Tenterfield Oration, the Corowa Conference, the referendums) that led to Australia's Federation and Constitution, including British and American influences on Australia's system of law and government (e.g. Magna Carta, federalism, constitutional monarchy, the Westminster system, the Houses of Parliament) Curriculum links are taken from: https://k10outline.scsa.wa.edu.au/home/p-10-curriculum/curriculum-browser/humanities-and-social- sciences Background information for teachers What is Federation? (in brief) Federation is the bringing together of colonies to form a nation with a federal (national) government. -

Inaugural Speeches in the NSW Parliament Briefing Paper No 4/2013 by Gareth Griffith

Inaugural speeches in the NSW Parliament Briefing Paper No 4/2013 by Gareth Griffith ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The author would like to thank officers from both Houses for their comments on a draft of this paper, in particular Stephanie Hesford and Jonathan Elliott from the Legislative Assembly and Stephen Frappell and Samuel Griffith from the Legislative Council. Thanks, too, to Lenny Roth and Greig Tillotson for their comments and advice. Any errors are the author’s responsibility. ISSN 1325-5142 ISBN 978 0 7313 1900 8 May 2013 © 2013 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior consent from the Manager, NSW Parliamentary Research Service, other than by Members of the New South Wales Parliament in the course of their official duties. Inaugural speeches in the NSW Parliament by Gareth Griffith NSW PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY RESEARCH SERVICE Gareth Griffith (BSc (Econ) (Hons), LLB (Hons), PhD), Manager, Politics & Government/Law .......................................... (02) 9230 2356 Lenny Roth (BCom, LLB), Acting Senior Research Officer, Law ............................................ (02) 9230 3085 Lynsey Blayden (BA, LLB (Hons)), Research Officer, Law ................................................................. (02) 9230 3085 Talina Drabsch (BA, LLB (Hons)), Research Officer, Social Issues/Law ........................................... (02) 9230 2484 Jack Finegan (BA (Hons), MSc), Research Officer, Environment/Planning..................................... (02) 9230 2906 Daniel Montoya (BEnvSc (Hons), PhD), Research Officer, Environment/Planning ..................................... (02) 9230 2003 John Wilkinson (MA, PhD), Research Officer, Economics ...................................................... (02) 9230 2006 Should Members or their staff require further information about this publication please contact the author. -

From Track to Tarmac

Federation Faces and Introduction A guided walk around the streets and laneways Places of North Sydney focusing on our Federation connections, including the former residences of A walking tour of Federation Sir Joseph Palmer Abbott, Sir Edmund Barton faces and places in North and Dugald Thomson. Along the walk, view the Sydney changes in the North Sydney landscape since th Federation and the turn of the 20 century. Distance: 6 Km Approximate time: 4 hours At the turn of the year 1900 to 1901 the city of Grading: medium to high Sydney went mad with joy. For a few days hope ran so high that poets and prophets declared Australia to be on the threshold of a golden age… from early morning on the first of January 1901 trams, trains and ferry boats carried thousands of people into the city for the greatest day of their history: the inauguration of the Commonwealth of Australia. It was to be a people‟s festival. Manning Clark, Historian It was also a people‟s movement and 1901 was the culmination of many years of discussions, community activism, heated public debates, vibrant speeches and consolidated actions. In 1890 the Australasian Federal Conference was held in Melbourne and the following year in Sydney. In 1893 a meeting of the various federation groups, including the Australian Native Association was held at Corowa. A plan was developed for the election of delegates to a convention. In the mid to late 1890s it was very much a peoples‟ movement gathering groundswell support. In 1896 a People‟s Convention with 220 delegates and invited guests from all of the colonies took place at Bathurst - an important link in the Federation chain. -

Papers on Parliament

‘But Once in a History’: Canberra’s David Headon Foundation Stones and Naming Ceremonies, 12 March 1913∗ When King O’Malley, the ‘legendary’ King O’Malley, penned the introduction to a book he had commissioned, in late 1913, he searched for just the right sequence of characteristically lofty, even visionary phrases. After all, as the Minister of Home Affairs in the progressive Labor government of Prime Minister Andrew Fisher, he had responsibility for establishing the new Australian nation’s capital city. Vigorous promotion of the idea, he knew, was essential. So, at the beginning of a book entitled Canberra: Capital City of the Commonwealth of Australia, telling the story of the milestone ‘foundation stones’ and ‘naming’ ceremonies that took place in Canberra, on 12 March 1913, O’Malley declared for posterity that ‘Such an opportunity as this, the Commonwealth selecting a site for its national city in almost virgin country, comes to few nations, and comes but once in a history’.1 This grand foundation narrative of Canberra—with its abundance of aspiration, ambition, high-mindedness, courage and curiosities—is still not well-enough known today. The city did not begin as a compromise between a feuding Sydney and Melbourne. Its roots comprise a far, far, better yarn than that. Unlike many major cities of the world, it was not created because of war, because of a revolution, disease, natural disaster or even to establish a convict settlement. Rather, a nation lucky enough to be looking for a capital city at the beginning of a new century knuckled down to the task with creativity and diligence. -

Miss Barbara West: a Lifelong Friend and Mentor Peter J. Hack Copyright

Miss Barbara West: A Lifelong Friend and Mentor Peter J. Hack Copyright © 2018 1 It is the 1930s. There is one city in China where women wear high heels and the latest Western hairstyles, and men dress in Western business suits. A city that celebrates all things modish and Western. Artists and architects, designers and decorators, dare to be modern. A city with nightclubs, where you might glimpse the actress Hu Die, the Butterfly. A city where art and culture burn bright. A city of glamour, but also a city of squalor and vice. A city with Western department stores established by Chinese-Australian merchants. This is Shanghai. For some, the Great Depression barely touches Shanghai. This is a place of riotous abundance. The rich and the famous continue to party in the Paris of the Orient. The buildings continue to rise. And the department stores continue to flourish on Nanking Road. And there is one store built in the latest art deco style that has the only escalators in China, has a rooftop garden, has air-conditioning on every floor and the largest porcelain department in Shanghai - the Sun Company department store. And one person who made this achievement possible is the Company Secretary, William Liu. Determined Reformers William Liu was born in Sydney in 1893, to a Chinese father and an English mother. At the age of seven in 1900, William was sent to China for a traditional Chinese education, returning to Australia in 1908. After eight years he needed to work on his English. At the age of seven, I and my younger brother Charlie went to Hong Kong, then inland China, to our father’s village, about a hundred miles1 south west of Hong Kong and Canton. -

Book Notes: the Sesquicentenary Committee

BOOK NOTES By David Clune * In a recent Book Note, two works sponsored by the Sesquicentenary of Responsible Government in NSW Committee were mentioned. As the Sesquicentenary year advances, readers of Australasian Parliamentary Review may be interested in a summary of what else has been published so far under the Committee’s auspices. The Sesquicentenary Committee is funding works on the major political parties and minor parties and independents in NSW. Michael Hogan’s Local Labor: A history of the Labor Party in Glebe, 1891–2003 (Federation Press, 2005) is a pioneering account of the ALP at grass roots level that also tells the story of Labor in NSW in microcosm. Recently published is Paul Davey’s The Nationals: The Progressive, Country and National Party in New South Wales 1919 to 2006 (Federation Press, 2006). A former journalist and Federal Director and NSW Secretary of the National Party, Paul Davey provides a sympathetic but balanced assessment of the Nationals and their predecessors. The Sesquicentenary Committee has combined with the State Records Authority of NSW to produce an administrative history of NSW. Hilary Golder’s Politics, Patronage and Public Works: The administration of New South Wales, Vol. 1, 1842–1900 (UNSW Press) was published in 2005. The next volume, Humble and Obedient Servants: The Administration of New South Wales 1901–1960 Vol. 2 by Peter J Tyler (UNSW Press) is now available. A Guide to New South Wales State Archives Relating to Responsible Government has also been published (State Records Authority of NSW, 2006). A number of biographical works have been sponsored. -

Re-Visioning Arts and Cultural Policy

Appendix B. Key moments in Australian arts and cultural policy development This appendix contains a detailed historical periodisation of Australian arts and cultural policy (Chart B.1) and a chronology of major events in the sector arranged according to government regimes and major reports to government (Chart B.2). David Throsby (2001) has identified three periods in Australian arts and cultural policy: · 1900-1967, when an explicit policy was `virtually non-existent'; · 1968-1990, when there was a `rapid expansion' of arts and cultural organisations and policies; and · 1990-2000, when there was a moderate expansion of the sector combined with the articulation of a broad cultural policy framework. This period also saw the development of an interest in the production of cultural statistics and monitoring of cultural trends in the light of policy shifts. This seems to borrow from Jennifer Radbourne's model that also identifies three broad periods: · 1940s-1967, establishment of Australian cultural organisations; · 1968-1975, establishment of semi-government finding organisations; and · 1975-present, arts as industry (Radbourne 1993). By contrast, I would offer this more elaborate model of cultural policy development: 75 Re-Visioning Arts and Cultural Policy Chart B.1 Period Characteristics Pre-1900 -Federation Colonial/state based models of cultural survival, moral regulation and assertion of Establishment of settler independence. Settler Cultures 1900-1939 Early state cultural entrepreneurialism particularly through the establishment of the State Cultural Australian Broadcasting Commission (e.g. orchestras, concert broadcasts, tours by Entrpreneurialism overseas artists) and development of commercial cultural entrepreneurs (such as J. C. Williamson). 1940-1954 Wartime state regulation of culture and communication; concern about external Setting Parameters of negative cultural influences (fascism, American black music, Hollywood films/popular Australian Culture culture) but apart from measures of regulation, ‘all talk no action’ in terms of cultural facilitation. -

Rural Ararat Heritage Study Volume 4

Rural Ararat Heritage Study Volume 4. Ararat Rural City Thematic Environmental History Prepared for Ararat Rural City Council by Dr Robyn Ballinger and Samantha Westbrooke March 2016 History in the Making This report was developed with the support PO Box 75 Maldon VIC 3463 of the Victorian State Government RURAL ARARAT HERITAGE STUDY – VOLUME 4 THEMATIC ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY Table of contents 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 The study area 1 1.2 The heritage significance of Ararat Rural City's landscape 3 2.0 The natural environment 4 2.1 Geomorphology and geology 4 2.1.1 West Victorian Uplands 4 2.1.2 Western Victorian Volcanic Plains 4 2.2 Vegetation 5 2.2.1 Vegetation types of the Western Victorian Uplands 5 2.2.2 Vegetation types of the Western Victoria Volcanic Plains 6 2.3 Climate 6 2.4 Waterways 6 2.5 Appreciating and protecting Victoria’s natural wonders 7 3.0 Peopling Victoria's places and landscapes 8 3.1 Living as Victoria’s original inhabitants 8 3.2 Exploring, surveying and mapping 10 3.3 Adapting to diverse environments 11 3.4 Migrating and making a home 13 3.5 Promoting settlement 14 3.5.1 Squatting 14 3.5.2 Land Sales 19 3.5.3 Settlement under the Land Acts 19 3.5.4 Closer settlement 22 3.5.5 Settlement since the 1960s 24 3.6 Fighting for survival 25 4.0 Connecting Victorians by transport 28 4.1 Establishing pathways 28 4.1.1 The first pathways and tracks 28 4.1.2 Coach routes 29 4.1.3 The gold escort route 29 4.1.4 Chinese tracks 30 4.1.5 Road making 30 4.2 Linking Victorians by rail 32 4.3 Linking Victorians by road in the 20th -

Proposed Redistribution of Victoria Into Electoral Divisions: April 2017

Proposed redistribution of Victoria into electoral divisions APRIL 2018 Report of the Redistribution Committee for Victoria Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 Feedback and enquiries Feedback on this report is welcome and should be directed to the contact officer. Contact officer National Redistributions Manager Roll Management and Community Engagement Branch Australian Electoral Commission 50 Marcus Clarke Street Canberra ACT 2600 Locked Bag 4007 Canberra ACT 2601 Telephone: 02 6271 4411 Fax: 02 6215 9999 Email: [email protected] AEC website www.aec.gov.au Accessible services Visit the AEC website for telephone interpreter services in other languages. Readers who are deaf or have a hearing or speech impairment can contact the AEC through the National Relay Service (NRS): – TTY users phone 133 677 and ask for 13 23 26 – Speak and Listen users phone 1300 555 727 and ask for 13 23 26 – Internet relay users connect to the NRS and ask for 13 23 26 ISBN: 978-1-921427-58-9 © Commonwealth of Australia 2018 © Victoria 2018 The report should be cited as Redistribution Committee for Victoria, Proposed redistribution of Victoria into electoral divisions. 18_0990 The Redistribution Committee for Victoria (the Redistribution Committee) has undertaken a proposed redistribution of Victoria. In developing the redistribution proposal, the Redistribution Committee has satisfied itself that the proposed electoral divisions meet the requirements of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (the Electoral Act). The Redistribution Committee commends its redistribution -

House of Representatives

SESSION 1906. THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH. ALPHABETICAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. SECOND PARLIAMENT. THIRD SESSION-7TH JUNE, 1906, TO 12TH OCTOBER, 1906. Votes Polled Division. for Sitting No. of Electors Name. Member. who Voted. Bamford, Hon. Frederick William ... Herbert, Queensland ... 8,965 16,241 Batchelor, Hon. Egerton Lee Boothby, South Australia ... 5,775 10,853 Blackwood, Robert Officer, Esq. * Riverina, New South Wales 4,341 8,887 Bonython, Hon. Sir John Langdon ... Barker, South Australia ... Unopposed Braddon, Right Hon. Sir Edward Nichcolas Wilmot, Tasmania S,13 6,144 Coventry, P.C., K.C.M.G. t Brown, Hon. Thomas ... ... Canobolas, New South Wales Unopposed Cameron, Hon. Donald Normant ... Wilmot, Tasmania 2,368 4,704 Carpenter, William Henry, Esquire .. Fremantle, Western Australia 3,439 6,021 Chanter, Hon. John Moore § ... ... Riverina, New South Wales 5,547 10,995 Chapman, Hon. Austin ... ... Eden-Monaro, New South Unopposed Wales Conroy, Hon. Alfred Hugh Beresford ... Werriwa, New South Wales 6,545 9,843 Cook, Hon. James Hume ... Bourke, Victoria ... 8,657 20,745 Cook, Hon. Joseph ... ... Parramatta, New South 10,097 13,215 Wales Crouch, Hon. Richard Armstrong ... Corio, Victoria ... 6,951 15,508 Culpin, Millice, Esquire ... Brisbane, Queensland ... 8,019 17,466 Deakin, Hon. Alfred ... ... Ballaarat, Victoria Unopposed Edwards, Hon. George Bertrand .. South Sydney, New South 9,662 17,769 Wales Edwards, Hon. Richard ... Oxley, Queensland ... 8,846 17,290 Ewing, Hon. Thomas Thomson ... Richmond, New South Wales 6,096 8,606 Fisher, Hon. Andrew ... Wide Bay, Queensland ... 10,622 17,698 Forrest, Right Hon. Sir John, P.C., Swan, Western Australia .. -

House of Representatives

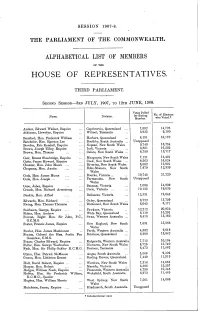

SESSION 1907-8. THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH. ALPHABETICAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. THIRD PARLIAMENT. SECOND SESSION-3RD JULY, 1907, TO 12TH JUNE, 1908. Votes Polled No. of Electors Name. Division. for Sitting Member. who Voted.* Archer, Edward Walker, Esquire Capricornia, Queensland ... 7,892 14,725 Atkinson, Llewelyn, Esquire Wilmot, Tasmania 3,935 9,100 Bamford, Hon. Frederick William Herbert, Queensland ... 8,151 16,170 Batchelor, Hon. Egerton Lee Boothby, South Australia ... Unopposed Bowden, Eric Kendall, Esquire Nepean, New South Wales 9,749 16,754 Brown, Joseph Tilley, Esquire Indi, Victoria 6,801 16,205 Brown, Hon. Thomas ... Calare, New South Wales ... 6,759 13,717 Carr, Ernest Shoobridge, Esquire Macquarie, New South Wales 7,121 14,401 Catts, James Howard, Esquire Cook, New South Wales .. 8,563 16,624 Chanter, Hon. John Moore ... Riverina, New South Wales 6,662 12,921 Chapman, Hon. Austin ... Eden-Monaro, New South 7,979 12,339 Wales Cook, Hon. James Hume ... Bourke, Victoria ... 10,745 21,220 Cook, Hon. Joseph ... Parramatta, New South Unopposed Wales Coon, Jabez, Esquire Batman, Victoria 7,098 14,939 Crouch, Hon. Richard Armstrong Corio, Victoria ... 10,135 19,035 Deakin, Hon. Alfred Ballaarat, Victoria 12,331 19,048 Edwards, Hon. Richard Oxley, Queensland 8,722 13,729 8,171 Ewing, Hon. Thomas Thomson Richmond, New South Wales 6,042 Fairbairn, George, Esquire ... Fawkner, Victoria 12,212 20,952 Fisher, Hon. Andrew ... Wide Bay, Queensland 8,118 15,291 Forrest, Right Hon. Sir John, P.C., Swan, Western Australia ... 8,418 13,163 G.C.M.G. -

Labor's Tortured Path to Protectionism

Labor's Tortured Path to Protectionism Phil Griffiths Department of Political Science, Australian National University Globalisation and economic rationalism have come to be associated organisations refused to support either free trade or protection, leaving with a wholesale attack on vital government services, jobs and it to the individual MP to vote as they saw fit, protectionist Victoria working conditions, and there is a debate inside the Australian labour being the exception. movement over what to do. Most of those opposed to the effects of Today we tend to think of tariff policy as having just one role, globalisation see the nation state as the only defence working people the protection of an industry from overseas competition, or, have against the power of market forces, and appeal to the Labor conversely, the opening of the Australian market to imports in order Party to shift back towards its traditional orientation to protectionism to ensure the international competitiveness of local industries. and state-directed economic development. However there has long However, in 190 I, there were three dimensions to the debates over been another, albeit minority, current on the left which rejects both tariffs: taxation, industry protection and class. For most colonies protectionism and free trade as bourgeois economic strategies before federation, especially Victoria, tariffs were the source ofmuch benefiting, not the working class, but rival groups of Australian government revenue, and a high level of revenue was vital for the capitalists: