Mr William Benjamin Chaffey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emerging Varieties of the Mediterranean

The Australian Wine Research Institute INTERNATIONAL SHIRAZ PRODUCTION AND PERFORMANCE Peter Dry AWRI ([email protected]) and Kym Anderson Univ Adelaide ([email protected]) The Australian Wine Research Institute International Shiraz production and The Australian Wine performance Research Institute Origin International plantings Recent history and development in other countries Importance in Australia Reasons for success in Australia Idiosyncrasies Climatic comparison The Australian Wine Where does Shiraz come from? Research Institute First documented in 1781 in northern Rhone . Small amounts of white grapes incl. Viognier used for blending Natural cross of Dureza♂ x Mondeuse Blanche♀ The Australian Wine Possible family tree Research Institute Source: Robinson et al. (2012) Winegrapes Pinot ? Mondeuse ? ? Noire ? Mondeuse ? Blanche Dureza Teroldego Viognier Syrah Lagrein The Australian Wine Hermitage Research Institute 0.0 1.0 2.0 3.0 4.0 5.0 6.0 7.0 wine area, area, wine (%) ofglobal shares varieties: 30 red Top Cabernet Sauvignon Merlot Tempranillo Syrah Garnacha Tinta Pinot Noir Mazuelo Bobal 2000 Sangiovese Monastrell Cabernet Franc Cot Alicante Henri … and Cinsaut Montepulciano Tribidrag 2010 Gamay Noir at downloadable freely Picture Empirical Global A are Grown Where? Varieties (2013) K. Anderson, Source: Isabella www.adelaide.edu.au/press/titles/winegrapes Barbera Douce Noire Criolla Grande Nero D'Avola Doukkali Blaufrankisch Prokupac Concord Touriga Franca Press. Adelaide of : University Negroamaro Carmenere Pinot Meunier Which Winegrape Research Institute Research WineAustralian The Bearing areas (ha) in major The Australian Wine countries: 2000 and 2010 Research Institute Source: Anderson 2014 National shares (%) of global winegrape The Australian Wine area of Shiraz, 2000 and 2010 Research Institute Source: Anderson 2014 60 50 2000 40 2010 30 20 10 0 The Australian Wine Recent history and distribution Research Institute France . -

Rural Ararat Heritage Study Volume 4

Rural Ararat Heritage Study Volume 4. Ararat Rural City Thematic Environmental History Prepared for Ararat Rural City Council by Dr Robyn Ballinger and Samantha Westbrooke March 2016 History in the Making This report was developed with the support PO Box 75 Maldon VIC 3463 of the Victorian State Government RURAL ARARAT HERITAGE STUDY – VOLUME 4 THEMATIC ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY Table of contents 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 The study area 1 1.2 The heritage significance of Ararat Rural City's landscape 3 2.0 The natural environment 4 2.1 Geomorphology and geology 4 2.1.1 West Victorian Uplands 4 2.1.2 Western Victorian Volcanic Plains 4 2.2 Vegetation 5 2.2.1 Vegetation types of the Western Victorian Uplands 5 2.2.2 Vegetation types of the Western Victoria Volcanic Plains 6 2.3 Climate 6 2.4 Waterways 6 2.5 Appreciating and protecting Victoria’s natural wonders 7 3.0 Peopling Victoria's places and landscapes 8 3.1 Living as Victoria’s original inhabitants 8 3.2 Exploring, surveying and mapping 10 3.3 Adapting to diverse environments 11 3.4 Migrating and making a home 13 3.5 Promoting settlement 14 3.5.1 Squatting 14 3.5.2 Land Sales 19 3.5.3 Settlement under the Land Acts 19 3.5.4 Closer settlement 22 3.5.5 Settlement since the 1960s 24 3.6 Fighting for survival 25 4.0 Connecting Victorians by transport 28 4.1 Establishing pathways 28 4.1.1 The first pathways and tracks 28 4.1.2 Coach routes 29 4.1.3 The gold escort route 29 4.1.4 Chinese tracks 30 4.1.5 Road making 30 4.2 Linking Victorians by rail 32 4.3 Linking Victorians by road in the 20th -

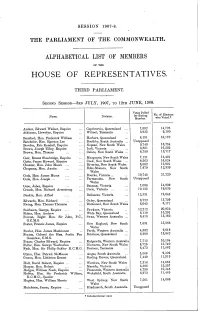

House of Representatives

SESSION 1907-8. THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH. ALPHABETICAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. THIRD PARLIAMENT. SECOND SESSION-3RD JULY, 1907, TO 12TH JUNE, 1908. Votes Polled No. of Electors Name. Division. for Sitting Member. who Voted.* Archer, Edward Walker, Esquire Capricornia, Queensland ... 7,892 14,725 Atkinson, Llewelyn, Esquire Wilmot, Tasmania 3,935 9,100 Bamford, Hon. Frederick William Herbert, Queensland ... 8,151 16,170 Batchelor, Hon. Egerton Lee Boothby, South Australia ... Unopposed Bowden, Eric Kendall, Esquire Nepean, New South Wales 9,749 16,754 Brown, Joseph Tilley, Esquire Indi, Victoria 6,801 16,205 Brown, Hon. Thomas ... Calare, New South Wales ... 6,759 13,717 Carr, Ernest Shoobridge, Esquire Macquarie, New South Wales 7,121 14,401 Catts, James Howard, Esquire Cook, New South Wales .. 8,563 16,624 Chanter, Hon. John Moore ... Riverina, New South Wales 6,662 12,921 Chapman, Hon. Austin ... Eden-Monaro, New South 7,979 12,339 Wales Cook, Hon. James Hume ... Bourke, Victoria ... 10,745 21,220 Cook, Hon. Joseph ... Parramatta, New South Unopposed Wales Coon, Jabez, Esquire Batman, Victoria 7,098 14,939 Crouch, Hon. Richard Armstrong Corio, Victoria ... 10,135 19,035 Deakin, Hon. Alfred Ballaarat, Victoria 12,331 19,048 Edwards, Hon. Richard Oxley, Queensland 8,722 13,729 8,171 Ewing, Hon. Thomas Thomson Richmond, New South Wales 6,042 Fairbairn, George, Esquire ... Fawkner, Victoria 12,212 20,952 Fisher, Hon. Andrew ... Wide Bay, Queensland 8,118 15,291 Forrest, Right Hon. Sir John, P.C., Swan, Western Australia ... 8,418 13,163 G.C.M.G. -

Research Commons at The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Commons@Waikato http://waikato.researchgateway.ac.nz/ Research Commons at the University of Waikato Copyright Statement: The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). The thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author’s right to be identified as the author of the thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. You will obtain the author’s permission before publishing any material from the thesis. Internationalization of the Yarra Valley Wine Industry Cluster A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Management Studies at The University of Waikato by Milan Sedoglavich ______________________________________ The University of Waikato 2009 Abstract This research investigates the ways in which firms in the cluster approach the process of internationalization through exploring the influence of business clustering and how it benefits firms in entering foreign markets. The purpose was to understand this process to enable firms to develop successful international strategies to expand in foreign markets. The focus of the study is on the Yarra Valley Wine Industry Cluster, the oldest wine growing region in Victoria, Australia. -

Growth Characteristics of Vitis Vinifera L. Cv. Cape Riesling A

Growth Characteristics of Vitis vinifera L. cv. Cape Riesling A. C. DE LA HARPEa, AND J. H. VISSERb (a) Viticultural and Oenological Research Institute, Private Bag X5026, 7600 Stellenbosch, Republic of South Africa. (b) Department of Botany, Univ. Stellenbosch, 7600 Stellenbosch, Republic of South Africa. Date submitted: September 1984 Date accepted: ~nuary 1985 . Keywords: Topping, growt( Vitis The effect of topping on the growth behaviour of Vitis vinifera L. cv. Cape Riesling vineyard was investigated. Shoot and leaf growth of both topped and untopped vines, can be described as sigmoidal. Shoot (cm) and leaf growth (cm') of the topped vines were significantly more than that of the untopped vines and are attributed to lateral shoot growth. Topping had no effect on bunch development. The development of skin, pulp and seed of both topped and untopped vines expressed as a percentage dry mass per berry can be described by a hyperbolic function for the skin, linear for the pulp and parabolic for the seed. Growth has been defined as "the advancement towards of topping on the growth characteristics of Vitis vinifera or attainment of full size or maturity; development: a L. cv. Cape Riesling. gradual increase in size and the process whereby plants and animals increase in size by taking in food" (Bidwell, 1974; Salisbury and Ross, 1978). Growth may be evaluated MATERIAL AND METHODS by measurements of mass, length, height, surface area or volume (Noggle and Fritz, 1976). Growth curves of plants Material: V. vinifera cv. Cape Riesling vines were selected are generally sigmoi"dal (Bidwell, 1974; Noggle and Fritz, as described by de la Harpe & Visser (1983). -

LORD HOPETOUN Papers, 1853-1904 Reels M936-37, M1154

AUSTRALIAN JOINT COPYING PROJECT LORD HOPETOUN Papers, 1853-1904 Reels M936-37, M1154-56, M1584 Rt. Hon. Marquess of Linlithgow Hopetoun House South Queensferry Lothian Scotland EH30 9SL National Library of Australia State Library of New South Wales Filmed: 1973, 1980, 1983 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE John Adrian Louis Hope (1860-1908), 7th Earl of Hopetoun (succeeded 1873), 1st Marquess of Linlithgow (created 1902), was born at Hopetoun House, near Edinburgh. He was educated at Eton and the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, but did not enter the Army. In 1883 he was appointed Conservative whip in the House of Lords and in 1885 was made a lord-in-waiting to Queen Victoria. In 1886 he married Hersey Moleyns, the daughter of Lord Ventry. In 1889 Lord Knutsford, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, appointed Hopetoun as Governor of Victoria and he held the post until March 1895. Although it was a time of economic depression, he entertained extravagantly, but his youthful enthusiasm and fondness for horseback tours of country districts won him considerable popularity. His term coincided with the first federation conferences and he supported the federation movement strongly. In 1895-98 Hopetoun was paymaster-general in the government of Lord Salisbury. In 1898 Joseph Chamberlain, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, offered him the post of Governor-General of Canada, but he declined. He was appointed Lord Chamberlain in 1898 and had a close association with members of the Royal Family. In July 1900 Hopetoun was appointed the first Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia. He arrived in Sydney on 15 December 1900 and his first task was to appoint the head of the new Commonwealth ministry. -

2007 Wfa Vintage Report

2007 WFA VINTAGE REPORT June 2007 Winegrape Intake falls to 1.42 million tonnes RED WINEGRAPE INTAKE (‘000 tonnes) The Australian wine industry’s grape intake fell in 2007, 500 with an estimated crush of 1.42 million tonnes – just over 2006 400 2007 25%, or 483,000 tonnes less than last year’s vintage of 1.90 million tonnes (ABS). 300 Red winegrape intake fell in 2007, from 1.04 million 200 tonnes to 678,000 tonnes, a decrease of 363,000 tonnes, and accounted for 48% of the total vintage. 100 White winegrape intake decreased by just under 120,000 0 Shiraz Cabernet Merlot Pinot Noir Ruby tonnes in 2007, or by 14.0%, to 741,000 tonnes, Sauvignon Cabernet representing 52% of the total intake. The reduction in the winegrape intake for 2007 can be White Intake Down 14% to 741,000 tonnes attributed to the combined effects of the drought, frosts and bushfire smoke taint. Chardonnay intake decreased by 8%, or by 33,300 tonnes to 395,000 tonnes. The share of the total winegrape crush accounted for by Chardonnay was 28% Red Intake Down 35% to 678,000 tonnes in 2007. Chardonnay is now the largest grape variety ahead of Shiraz, and well ahead of Cabernet Sauvignon. Shiraz intake decreased by 36%, or by 161,000 tonnes to Semillon intake dropped by 25%, to 77,300 tonnes, and about 293,000 tonnes, and lost its dominance as represents 5% of the total grape crush. Australia’s largest winegrape variety, accounting for 21% of the total intake. -

Cocktails Wines by the Glass Beer Non-Alcoholic Wines of the World

Wines of the World white/rosé/red sparkling Aligoté/chardonnay dom. deliance, bourgogne, nv 64 Chardonnay le brun servenay, grand cru champagne, nv 100 Cocktails Chard/pinot noir geoffroy, “voluptÉ”, 1er cru champagne, 2009 145 Frappato rosÉ cos, “extra brut”, sicily, 2013 99 Lemonnana Dolcetto rosÉ pét-nat konpira maru, victoria, 2019 56 glass/pitcher 11/39 Marzemino pét-nat alice, “m fondo”, veneto, nv 58 jim beam, muddled mint, fresh lemon, verbena white/rosé/skin contact Pinot gouges chad stock, “origin”, eola-amity hills, 2017 88 Marble rye 13 pumpernickel & caraway-infused Pinela guerila, vipava valley, 2018 65 jim beam rye, celery Riesling abbazia di novacella, alto adige, 2018 65 Riesling domaine paul blanc, “classique”, alsace, 2018 73 The z&t 13 Riesling schloss gobelsburg, “zöbing”, kamptal, 2016 82 gin, za’atar, byrrh ListÁn blanco borja perez, canary islands, 2017 67 Gruner veltliner hirsch, “kammern”, kamptal, 2017 76 The zeppelin 13 Arinto poÇo do lobo, beiras, 1994 112 combier rose, lillet, dolin blanc, Viura/garnacha blanca sierra de la demanda, rioja, 2015 82 cava Chardonnay rÉmi jobard, “les narvaux”, meursault, 2017 185 Chardonnay louis moreau, “les clos”, chablis grand cru, 2016 195 Change with the times 14 Riesling ross & bee maloof, chehalem mountains, 2018 (1.5l) 110 barrel finished gin, Müller-thurgau (skin contact) enderle & moll, baden, 2018 59 pomegranate, citrus, bitters Riesling/mÜller (skin contact) brianne day, oregon, 2019 62 Ribolla gialla (skin contact) ross & bee maloof, oregon, 2018 82 Whiskey harif -

Wine Production and Terroir in Mclaren Vale, South Australia

Fermenting Place Wine production and terroir in McLaren Vale, South Australia William Skinner Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the Discipline of Anthropology, School of Social Sciences University of Adelaide September 2015 Table of Contents List of Figures ...................................................................................................................... iv Abstract .............................................................................................................................. vi Declaration ....................................................................................................................... viii Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ ix Introduction ........................................................................................................................1 Framing the thesis .............................................................................................................. 4 Dwelling, place and landscape ............................................................................................ 6 Relationality ...................................................................................................................... 15 A terroir perspective ......................................................................................................... 18 Learning from people and vines ...................................................................................... -

Choosing Alternative Grapevine Varieties for the Padthaway, Mt Benson and Robe Regions of the Limestone Coast

Choosing alternative grapevine varieties for the Padthaway, Mt Benson and Robe regions of the Limestone Coast Prepared by Libby Tassie Viticulturist Tassie Viticultural Consulting Date August 2016 Contents AIM ................................................................................................................................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................. 1 INVESTIGATION OF VARIETAL OPTIONS .......................................................................................................... 2 FACTORS TO CONSIDER WHEN CHOOSING ALTERNATIVE VARIETIES .............................................................. 4 1. CLIMATE AND CLIMATIC COMPARISONS .............................................................................................. 4 1.1. TEMPERATURE AND TEMPERATURE INDICES ..................................................................................................... 6 1.1.1. Mean January/July temperature (MJT) ........................................................................................... 6 1.1.2. Heat degree days (HDD) .................................................................................................................. 7 1.1.3. Other temperature indices ............................................................................................................. 7 1.2. OTHER CLIMATIC FACTORS .......................................................................................................................... -

Vintage Report

Appendix B July 2015 Vintage Report WFA winegrape crush and 2016 outlook Overview Total Winegrape Crush in Australia This year’s Vintage Report includes some positive signs for the industry. 1900 Along with shifts in the macro-economic climate – including favorable 8 year average: 1.699 million tonnes shifts in exchange rates, the signing of key Free Trade Agreements 1850 1800 and strengthening consumer demand in some key market segments 2015 crush: 1.67 million – the outlook for the industry has improved from last year. However, 1750 tonnes the Report also indicates an industry under sustained profit pressure 1700 and the persistence of a structural mismatch between the supply and 1650 demand for our wine at profitable price points. ‘000 tonnes 1600 The 2015 Vintage of 1.67 million tonnes which is marginally lower than 1550 “average” and while average grape prices have strengthened, 1500 this is off a low base. 1450 1400 Favorable changes in seasonal market conditions and the macro- economic environment will not be enough to restore the Australian wine sector’s lost share and margin. We need to take pro-active steps 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 with the support of government to boost demand and our resourcing Average Crush Grape Crush of promotional activities. On the supply side, better informed decision Sources: Historical crush figures – Levies Revenue Service (LRS), ABS and WFA making is required with the aid of improved data, analysis and price signaling. This Report is part of that data set. 2015 winegrape crush This year the WFA Vintage Survey was combined with the Wine The 2015 Australian grape crush is 1.67 million tonnes – just a 0.4% Australia Price Dispersion Survey, the South Australian Grape Crush increase from last year’s Levies Finance 2014 recorded crush of 1.66 Survey and the Murray-Darling / Swan Hill Wine Grape Crush Report million tonnes1. -

Laying Down Detailed Rules for the Description and Presentation of Wines and Grape Musts

8 . 11 . 90 Official Journal of the European Communities No L 309 / 1 I (Acts whose publication is obligatory) COMMISSION REGULATION (EEC) No 3201 /90 of 16 October 1990 laying down detailed rules for the description and presentation of wines and grape musts THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, frequently been amended; whereas, in the interests of clarity, and on the occasion of further amendments, the rules in question should be consolidated; Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community, Whereas, in applying rules concerning the description and presentation of wines, the traditional and customary practices of the Community wine-growing regions should Having regard to Council Regulation (EEC) No 822/ 87 of be taken into account to the extent that the traditional and 16 March 1987 on the common organization of the market customary practices are compatible with the principles of a in wine ( 3 ), as last amended by Regulation ( EEC) single market; whereas it is also necessary to avoid any No 1325 / 90 ( 2 ), and in particular Articles 72 ( 5 ) and 81 confusion in the use of expressions employed in labelling thereof, and to ensure that the information on the label is as clear and complete as possible for the consumer; Whereas Council Regulation ( EEC ) No 2392/ 89 (3 ), as amended by Regulation ( EEC ) No 3886 / 89 (4), lays down Whereas, in order to allow the bottler some freedom as general rules for the description and presentation of wines regards the manner in which he presents the mandatory and grape