Papers on Parliament

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

House of Representatives

SESSION 1906. THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH. ALPHABETICAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. SECOND PARLIAMENT. THIRD SESSION-7TH JUNE, 1906, TO 12TH OCTOBER, 1906. Votes Polled Division. for Sitting No. of Electors Name. Member. who Voted. Bamford, Hon. Frederick William ... Herbert, Queensland ... 8,965 16,241 Batchelor, Hon. Egerton Lee Boothby, South Australia ... 5,775 10,853 Blackwood, Robert Officer, Esq. * Riverina, New South Wales 4,341 8,887 Bonython, Hon. Sir John Langdon ... Barker, South Australia ... Unopposed Braddon, Right Hon. Sir Edward Nichcolas Wilmot, Tasmania S,13 6,144 Coventry, P.C., K.C.M.G. t Brown, Hon. Thomas ... ... Canobolas, New South Wales Unopposed Cameron, Hon. Donald Normant ... Wilmot, Tasmania 2,368 4,704 Carpenter, William Henry, Esquire .. Fremantle, Western Australia 3,439 6,021 Chanter, Hon. John Moore § ... ... Riverina, New South Wales 5,547 10,995 Chapman, Hon. Austin ... ... Eden-Monaro, New South Unopposed Wales Conroy, Hon. Alfred Hugh Beresford ... Werriwa, New South Wales 6,545 9,843 Cook, Hon. James Hume ... Bourke, Victoria ... 8,657 20,745 Cook, Hon. Joseph ... ... Parramatta, New South 10,097 13,215 Wales Crouch, Hon. Richard Armstrong ... Corio, Victoria ... 6,951 15,508 Culpin, Millice, Esquire ... Brisbane, Queensland ... 8,019 17,466 Deakin, Hon. Alfred ... ... Ballaarat, Victoria Unopposed Edwards, Hon. George Bertrand .. South Sydney, New South 9,662 17,769 Wales Edwards, Hon. Richard ... Oxley, Queensland ... 8,846 17,290 Ewing, Hon. Thomas Thomson ... Richmond, New South Wales 6,096 8,606 Fisher, Hon. Andrew ... Wide Bay, Queensland ... 10,622 17,698 Forrest, Right Hon. Sir John, P.C., Swan, Western Australia .. -

John Gale and Huntly

NATIONALTRUST OF AUSTRALIA (ACT) John Gale and Huntly John Gale in the Bamboo Room, Huntly This article originally appeared in Heritage in Trust as John Gale and Life at Huntly in two parts in November 2011 and February 2012 issues. ADPBC32.tmp 1 26/01/2016 11:01:07 AM John Gale and Huntly National Trust of Australia (ACT) February 2016 The article republished here was based on an interview by Di Johnstone with John Gale, owner of the historic property, Huntly, and originally published in Heritage in Trust in two parts in November 2011 and February 2012 issues. It is republished here in commemoration of John Gale and his contribution to the heritage of the ACT and to the National Trust (ACT) on the occasion of the auction of the contents of the house in February 2016 due to John no longer being able to live at Huntly. Auction catalogue (Photos this page: Leonard Joel Auction House) Mark Grey-Smith statue Part of the “donkey collection” Members will know John Gale OBE, a long-standing and Life Member of the National Trust ACT, who has most generously opened his home at Huntly and its lovely garden for National Trust functions and for many other charities and community organizations. In this interview, which led up to Canberra’s Centenary, over tea and home-baked scones in the sun-filled Bamboo Room of Huntly, overlooking the garden, John Gale reflects on his life at Huntly and in the Canberra District in earlier times and tells some special stories. This account builds on excellent articles by Judith Baskin in 1999 about the garden at Huntly and in 2008 about Huntly itself. -

Earle Page and the Imagining of Australia

‘NOW IS THE PSYCHOLOGICAL MOMENT’ EARLE PAGE AND THE IMAGINING OF AUSTRALIA ‘NOW IS THE PSYCHOLOGICAL MOMENT’ EARLE PAGE AND THE IMAGINING OF AUSTRALIA STEPHEN WILKS Ah, but a man’s reach should exceed his grasp, Or what’s a heaven for? Robert Browning, ‘Andrea del Sarto’ The man who makes no mistakes does not usually make anything. Edward John Phelps Earle Page as seen by L.F. Reynolds in Table Talk, 21 October 1926. Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760463670 ISBN (online): 9781760463687 WorldCat (print): 1198529303 WorldCat (online): 1198529152 DOI: 10.22459/NPM.2020 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This publication was awarded a College of Arts and Social Sciences PhD Publication Prize in 2018. The prize contributes to the cost of professional copyediting. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: Earle Page strikes a pose in early Canberra. Mildenhall Collection, NAA, A3560, 6053, undated. This edition © 2020 ANU Press CONTENTS Illustrations . ix Acknowledgements . xi Abbreviations . xiii Prologue: ‘How Many Germans Did You Kill, Doc?’ . xv Introduction: ‘A Dreamer of Dreams’ . 1 1 . Family, Community and Methodism: The Forging of Page’s World View . .. 17 2 . ‘We Were Determined to Use Our Opportunities to the Full’: Page’s Rise to National Prominence . -

Founding Families of Ipswich Pre 1900: M-Z

Founding Families of Ipswich Pre 1900: M-Z Name Arrival date Biographical details Macartney (nee McGowan), Fanny B. 13.02.1841 in Ireland. D. 23.02.1873 in Ipswich. Arrived in QLD 02.09.1864 on board the ‘Young England’ and in Ipswich the same year on board the Steamer ‘Settler’. Occupation: Home Duties. Macartney, John B. 11.07.1840 in Ireland. D. 19.03.1927 in Ipswich. Arrived in QLD 02.09.1864 on board the ‘Young England’ and in Ipswich the same year on board the Steamer ‘Settler’. Lived at Flint St, Nth Ipswich. Occupation: Engine Driver for QLD Government Railways. MacDonald, Robina 1865 (Drayton) B. 03.03.1865. D. 27.12.1947. Occupation: Seamstress. Married Alexander 1867 (Ipswich) approx. Fairweather. MacDonald (nee Barclay), Robina 1865 (Moreton Bay) B. 1834. D. 27.12.1908. Married to William MacDonald. Lived in Canning Street, 1865 – approx 26 Aug (Ipswich) North Ipswich. Occupation: Housewife. MacDonald, William 1865 (Moreton Bay) B. 13.04.1837. D. 26.11.1913. William lived in Canning Street, North Ipswich. 1865 – approx 26 Aug (Ipswich) Occupation: Blacksmith. MacFarlane, John 1862 (Australia) B. 1829. John established a drapery business in Ipswich. He was an Alderman of Ipswich City Council in 1873-1875, 1877-1878; Mayor of Ipswich in 1876; a member of Parliament from 1877-1894; a member of a group who established the Woollen Mill in 1875 of which he became a Director; and a member of the Ipswich Hospital Board. John MacFarlane lived at 1 Deebing Street, Denmark Hill and built a house on the corner of Waghorn and Chelmsford Avenue, Denmark Hill. -

The Life of Quong Tart Or, How a Foreigner Succeeded in a British Community

The Life of Quong Tart or, How A Foreigner Succeeded in A British Community Tart, Margaret A digital text sponsored by New South Wales Centenary of Federation Committee University of Sydney Library Sydney 2001 http://setis.library.usyd.edu.au/fed/ © University of Sydney Library. The texts and Images are not to be used for commercial purposes without permission Source Text: Prepared from the print edition published by W. M. Maclardy, “Ben Franklin” Printing Works Sydney 1911 All quotation marks retained as data All unambiguous end-of-line hyphens have been removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to the preceding line. First Published: 1911 Languages: French Australian Etexts 1910-1939 chinese in australia biographies women writers prose nonfiction federation 2001 Creagh Cole Coordinator Final Checking and Parsing The Life of Quong Tart: or, How A Foreigner Succeeded in A British Community Compiled and Edited by Mrs Quong Tart Sydney W. M. Maclardy, “Ben Franklin” Printing Works 1911 Contents AUTHOR'S INTRODUCTION 4 SUMMARY OF LIFE 5 MARRIAGE 11 BUSINESS MAN 18 PUBLIC BENEFACTOR 25 WORK ON BEHALF OF THE CHINESE (GENERAL OUTLINE) 31 VIEWS AND WORK ON THE SUPPRESSION OF OPIUM 46 SPORTSMAN 58 HUMOROUS REMARKS BY HIM AND ABOUT HIM 60 COMPLIMENTARY LETTERS AND ADDRESSES RECEIVED BY HIM 67 MURDEROUS ASSAULT ON HIM AND CITIZENS SYMPATHY WITH HIM 84 NAMES OF CONTRIBUTORS TO THE PUBLIC TESTIMONIAL 90 DEATH AND FUNERAL 96 Introduction. Author's Notes. This book contains the biography of the late Quong Tart, and was begun on the seventh anniversary of his death. -

The Life and Times of Sir John Waters Kirwan (1866-1949)

‘Mightier than the Sword’: The Life and Times of Sir John Waters Kirwan (1866-1949) By Anne Partlon MA (Eng) and Grad. Dip. Ed This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Murdoch University 2011 I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not been previously submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. ............................................................... Anne Partlon ii Table of Contents Abstract iv Acknowledgements v Introduction: A Most Unsuitable Candidate 1 Chapter 1:The Kirwans of Woodfield 14 Chapter 2:‘Bound for South Australia’ 29 Chapter 3: ‘Westward Ho’ 56 Chapter 4: ‘How the West was Won’ 72 Chapter 5: The Honorable Member for Kalgoorlie 100 Chapter 6: The Great Train Robbery 120 Chapter 7: Changes 149 Chapter 8: War and Peace 178 Chapter 9: Epilogue: Last Post 214 Conclusion 231 Bibliography 238 iii Abstract John Waters Kirwan (1866-1949) played a pivotal role in the Australian Federal movement. At a time when the Premier of Western Australia Sir John Forrest had begun to doubt the wisdom of his resource rich but under-developed colony joining the emerging Commonwealth, Kirwan conspired with Perth Federalists, Walter James and George Leake, to force Forrest’s hand. Editor and part- owner of the influential Kalgoorlie Miner, the ‘pocket-handkerchief’ newspaper he had transformed into one of the most powerful journals in the colony, he waged a virulent press campaign against the besieged Premier, mocking and belittling him at every turn and encouraging his east coast colleagues to follow suit. -

Conservation Management Plan

PHILIP LEESON ARCHITECTS Main Truss Spans Charles Dearling 2006 CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN THARWA BRIDGE for ROADS ACT by PHILIP LEESON ARCHITECTS PTY LTD ENDORSED BY THE ACT HERITAGE COUNCIL ON 5TH MARCH 2009 THARWA BRIDGE CMP MARCH 2009 PHILIP LEESON ARCHITECTS pg.1 CONTENTS PAGE 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 2.0 INTRODUCTION 3 3.0 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 6 4.0 PHYSICAL ASSESSMENT 21 5.0 ASSESSMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE 40 6.0 OPPORTUNITIES & CONSTRAINTS 44 7.0 CONSERVATION POLICIES 45 8.0 IMPLEMENTATION STRATEGIES 49 9.0 REFERENCES 55 10.0 APPENDICES 59 1 Timeline of the Murrumbidgee River Crossing 60 and Tharwa Bridge 2 Discussion of Reconstruction Proposals 78 3 Typical Cyclical Maintenance Schedule 84 4 Problems Encountered with Timber Truss Bridges 88 5 Tharwa Bridge Heritage Significance Study 95 THARWA BRIDGE CMP MARCH 2009 PHILIP LEESON ARCHITECTS pg.2 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1 This Conservation Management Plan has been prepared for Roads ACT in accordance with the conservation principles outlined in the Australia ICOMOS Burra Charter 1999. 1.2 The Plan consists of a comprehensive conservation analysis based on historical and physical overview, an assessment of cultural significance, conservation policies for the bridge and surrounds and strategies for implementation of those policies. Appendices provide a detailed chronology of historical events, a brief discussion of the heritage impact of likely proposals and a typical maintenance program. 1.3 Tharwa Bridge was listed on the ACT Heritage Register in 1998 at which time a brief assessment of significance was undertaken and a citation written. It was listed on the Register of the National Estate in 1983. -

Alfred Deakin's Letters to the London Morning Post

From Our Special Correspondent: From Our Special Correspondent: Alfred Deakin’s letters to the London Morning Post Alfred Deakin’s letters to the London Deakin’s Alfred Morning Post Morning Volume 3: 1903 Australian Parliamentary Library Department of Parliamentary Services From Our Special Correspondent: Alfred Deakin’s letters to the London Morning Post Volume 3 1903 © Commonwealth of Australia 2020 Published by: Australian Parliamentary Library Department of Parliamentary Services Parliament House Canberra First published in 2020 Series: From Our Special Correspondent: Alfred Deakin’s letters to the London Morning Post Series editor: Dianne Heriot Layout and design: Matthew Harris Printed and bound by: Bytes N Colours Braddon Australian Capital Territory From Our Special Correspondent: Alfred Deakin’s letters to the London Morning Post; Volume 3: 1903 ISBN: 978-0-9875764-3-9 Front cover: Advance Australia: postcard of Alfred Deakin with selected flora and fauna of Australia and a composite coat of arms, printed between 1903 and 1910. (National Library of Australia, nla.obj-153093943) ii Portrait of Alfred Deakin, Elliott & Fry, 190-? (National Library of Australia, nla.obj-136656912) iii Acknowledgements This collection of Deakin’s letters to the Morning Post has been in progress for a number of years, and continues so to be. The Parliamentary Library would like to acknowledge the assistance of the following organisations and individuals who have contributed expertise, permission to use images or archival records, or access to their collections, as follows: National Library of Australia; National Archives of Australia; Julia Adam; Rowena Billing; Barbara Coe; Carlene Dunshea; Jonathon Guppy; Matthew Harris; Joanne James; Maryanne Lawless; Matthew Smith and Ellen Weaver. -

Story of Herbert Joseph Dixie 1861-1904 Compiled by Dale

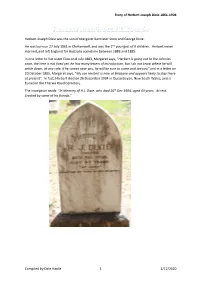

Story of Herbert Joseph Dixie 1861-1904 Herbert Joseph Dixie was the son of Margaret Bannister Stow and George Dixie. He was born on 27 July 1861 in Clerkenwell, and was the 2nd youngest of 9 children. Herbert never married, and left England for Australia sometime between 1883 and 1885. In one letter to her sister Eliza on 8 July 1883, Margaret says, “Herbert is going out to the colonies soon, the time is not fixed yet, he has many letters of introduction, but I do not know where he will settle down, at any rate, if he comes near you, he will be sure to come and see you” and in a letter on 20 October 1885, Margaret says, “My son Herbert is now at Brisbane and appears likely to stay there at present”. In fact, Herbert died on 26 December 1904 in Queanbeyan, New South Wales, and is buried in the Tharwa Road Cemetery. The inscription reads: “In Memory of H.J. Dixie, who died 26th Dec 1904, aged 43 years. At rest. Erected by some of his friends.” Compiled by Dale Hartle 1 2/12/2020 Story of Herbert Joseph Dixie 1861-1904 Herbert’s lengthy and impressive Obituary was published in The Age (Queanbeyan NSW) on Friday 30 Dec 19041 and it outlines his life in Australia and the details of his death and funeral: Obituary MR HERBERT JOSEPH DIXIE Great sympathy was felt by the whole of the Queanbeyan community when, on Monday evening, flags were hoisted half-mast announcing that Alderman H. J. Dixie had passed over to the great majority. -

Undiscovered Canberra Allan J.Mortlock Bernice Anderson This Book Was Published by ANU Press Between 1965–1991

Undiscovered Canberra Allan J.Mortlock Bernice Anderson This book was published by ANU Press between 1965–1991. This republication is part of the digitisation project being carried out by Scholarly Information Services/Library and ANU Press. This project aims to make past scholarly works published by The Australian National University available to a global audience under its open-access policy. Undiscovered Canberra A collection of different places to visit, things to do and walks to take in and near Canberra. Allan J. Mortlock and Bernice Anderson 1 EDIT • A l DEPARTMENT- ■mill wi Sfiiiiiiiil U i'niiiin P-b' BLiCATlON DATE m i-H Australian National University Press, Canberra, Australia and Norwalk Conn. 1978 First published in Australia 1978 Printed in Hong Kong for the Australian National University Press, Canberra ® Allan J. Mortlockand Bernice Anderson 1978 This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism, or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Mortlock, Allan John. Undiscovered Canberra. (Canberra companions). ISBN 0 7081 1579 9. 1. Australian Capital Territory — Description and travel — Guide-books. I. Anderson, Bernice Irene, joint author. II. Title. (Series). 919.47 Library of Congress No. 78-51763 North America: Books Australia, Norwalk, Conn., USA Southeast Asia: Angus & Robertson (S.E.Asia) Pty Ltd, Singapore Japan: United Publishers Services Ltd, Tokyo Cover photograph Robert Cooper Designed by ANU Graphic Design/Adrian Young Typesetting by TypoGraphics Communications, Sydney Printed by Colorcraft, Hong Kong Introduction Visitors to Canberra, and indeed locals also, are often heard to remark that there is little to do in our national capital. -

The Foundation and Early History of Catholic Church Insurances (Cci) 1900-1936

THE FOUNDATION AND EARLY HISTORY OF CATHOLIC CHURCH INSURANCES (CCI) 1900-1936 Submitted by JANE MAYO CAROLAN BA (University of Melbourne); Grad Dip Lib (RMIT University); MA History (University of Melbourne) A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Theology Faculty of Theology and Philosophy Australian Catholic University Research Services Locked Bag 2002 Strathfield, New South Wales 2135 Australia November 2015 i STATEMENT OF SOURCES This thesis contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or part from a thesis by which I have qualified for or been awarded another degree or diploma. No other person’s work has been used without due acknowledgement in the main text of the thesis. This thesis has not been submitted for the award of any degree or diploma in any other tertiary institution. Signed __________________________ Date: 28 November 2015 ii DEDICATION To my husband Kevin James Carolan, our children Thomas, Miriam, Ralph and Andrew and our grandchildren, Sophie, Lara, Samuel and Katherine, for their loving patience and support. Many colleagues and friends provided assistance including Dr. Sophie McGrath rsm, Professor James McLaren and Professor Shurlee Swain of ACU. Wonderful insights and advice were offered by outside academics, Dr Jeff Kildea, Dr Simon Smith and Associate Professor Bronwyn Naylor. iii ABSTRACT In the early twentieth century Cardinal Patrick Moran and others, both clerical and lay, understood that the adolescent Australian Catholic Church needed physical as well as spiritual support. The Church, as trustee, had an economic imperative to care for and maintain its properties. -

Votes and Proceedings House Of

'149 1903. THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH. No. 66. VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. THURSDAY, 24TH SEPTEMBER, 1903. 1. The House met pursuant to adjournment.-Mr. Speaker took the Chair, and read Prayers. 2. RESIGNATION OF PRIME MINISTER, AND CONSEQUENT FORMATION OF NEW MINISTRY.-Mr. Deakin informed the House that the Prime Minister had that morning tendered his resignation to the Governor-General, and that His Excellency had been pleased to accept the same, and had cast upon him (Mr. Deakin) the duty of continuing the Government. The new Government had been formed as follows:- Prime Minister and Minister of State for External Affairs-The Honorable Alfred Deakin, Minister of State for Trade and Customs-The Honorable Sir William Lyne, Treasurer-The Right Honorable Sir George Turner, Minister of State for Home Affairs-The Right Honorable Sir John Forrest, Attorney-General-The Honorable J. G. Drake, Postmaster-General-The Honorable Sir Philip Fysh, Minister of State for Defence-The Honorable Austin Chapman, and Vice-President of the Federal Executive Council-The Honorable Thomas Playford. The late Prime Minister had communicated by telegram with the present Chief Justice of Queensland, and had that morning received from him a reply accepting the offer of the Chief Justiceship of the High Court of the Commonwealth. Since the resignation of Sir Edmund Barton, the new Ministry had offered to Sir Edmund Barton and to Senator O'Connor the positions of Justices of the High Court, and they had accepted them. New Ministers would be sworn in that afternoon. 3. SPECIAL ADJOURNMENT.-Mr.