The Life of Quong Tart Or, How a Foreigner Succeeded in a British Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Papers on Parliament

‘But Once in a History’: Canberra’s David Headon Foundation Stones and Naming Ceremonies, 12 March 1913∗ When King O’Malley, the ‘legendary’ King O’Malley, penned the introduction to a book he had commissioned, in late 1913, he searched for just the right sequence of characteristically lofty, even visionary phrases. After all, as the Minister of Home Affairs in the progressive Labor government of Prime Minister Andrew Fisher, he had responsibility for establishing the new Australian nation’s capital city. Vigorous promotion of the idea, he knew, was essential. So, at the beginning of a book entitled Canberra: Capital City of the Commonwealth of Australia, telling the story of the milestone ‘foundation stones’ and ‘naming’ ceremonies that took place in Canberra, on 12 March 1913, O’Malley declared for posterity that ‘Such an opportunity as this, the Commonwealth selecting a site for its national city in almost virgin country, comes to few nations, and comes but once in a history’.1 This grand foundation narrative of Canberra—with its abundance of aspiration, ambition, high-mindedness, courage and curiosities—is still not well-enough known today. The city did not begin as a compromise between a feuding Sydney and Melbourne. Its roots comprise a far, far, better yarn than that. Unlike many major cities of the world, it was not created because of war, because of a revolution, disease, natural disaster or even to establish a convict settlement. Rather, a nation lucky enough to be looking for a capital city at the beginning of a new century knuckled down to the task with creativity and diligence. -

John Gale and Huntly

NATIONALTRUST OF AUSTRALIA (ACT) John Gale and Huntly John Gale in the Bamboo Room, Huntly This article originally appeared in Heritage in Trust as John Gale and Life at Huntly in two parts in November 2011 and February 2012 issues. ADPBC32.tmp 1 26/01/2016 11:01:07 AM John Gale and Huntly National Trust of Australia (ACT) February 2016 The article republished here was based on an interview by Di Johnstone with John Gale, owner of the historic property, Huntly, and originally published in Heritage in Trust in two parts in November 2011 and February 2012 issues. It is republished here in commemoration of John Gale and his contribution to the heritage of the ACT and to the National Trust (ACT) on the occasion of the auction of the contents of the house in February 2016 due to John no longer being able to live at Huntly. Auction catalogue (Photos this page: Leonard Joel Auction House) Mark Grey-Smith statue Part of the “donkey collection” Members will know John Gale OBE, a long-standing and Life Member of the National Trust ACT, who has most generously opened his home at Huntly and its lovely garden for National Trust functions and for many other charities and community organizations. In this interview, which led up to Canberra’s Centenary, over tea and home-baked scones in the sun-filled Bamboo Room of Huntly, overlooking the garden, John Gale reflects on his life at Huntly and in the Canberra District in earlier times and tells some special stories. This account builds on excellent articles by Judith Baskin in 1999 about the garden at Huntly and in 2008 about Huntly itself. -

2-20 Praeclarum.Indd

For Rolls-Royce and Bentley Enthusiasts PRÆCLARVM The National Journal of the Rolls-Royce Owners’ Club of Australia No. 2-20 April 2020 AX201 finds a New Owner Quidvis recte factvm quamvis hvmile præclarvm Whatever is rightly done, however humble, is noble. Royce, 1924 PRÆCLARVM The National Journal of the Rolls-Royce Owners’ Club of Australia No. 2-20 April 2020 Issue 307 Regular Items Features Events Calendar 7779 From the Editor 7780 From the Federal President 7781 News from the Registers 7802 Book Reviews 7807 Market Place 7809 Articles and Features From the Sir Henry Royce Foundation: Russell Rolls, Chairman of Trustees, 7782 SHRF, gives the details of the recent loan and refurbishment of a Rolls-Royce diesel 'Eagle' truck engine for display at to the SHRF's Coolum, Qld, Museum. Photo: Gil Fuqua (USA) Photo: Rolls-Royce’s most iconic car, AX201, fi nds an enthusiastic new owner: 7783 Præclarvm is pleased to advise that Sir Michael After a period of mistaken rumours, David Berthon (NSW) is able to let Kadoorie of Hong Kong is the mystery buyer of Præclarvm lead with the news that Sir Michael Kadoorie, of Hong Kong, is the Rolls-Royce AX201 "Silver Ghost". Read David excited to have purchased the iconic AX201, "Silver Ghost". Berthon's story of the sale on page 7783. Oscar Asche, the 1910 Silver Ghost, 1237, and Two Versions of Chu Chin 7786 Chow. Ian Irwin (ACT) has been searching the Country's various Archives to present a story that centres around early Rolls-Royce motoring history. 1975 Silver Shadow Saloon (SRH22160) Successfully Completes the 2019 7788 Peking to Paris Rally (Part 4): Brothers, Steve and Alan Maden (Vic) fulfi lled a long-term desire and completed the 2019 Rally. -

Founding Families of Ipswich Pre 1900: M-Z

Founding Families of Ipswich Pre 1900: M-Z Name Arrival date Biographical details Macartney (nee McGowan), Fanny B. 13.02.1841 in Ireland. D. 23.02.1873 in Ipswich. Arrived in QLD 02.09.1864 on board the ‘Young England’ and in Ipswich the same year on board the Steamer ‘Settler’. Occupation: Home Duties. Macartney, John B. 11.07.1840 in Ireland. D. 19.03.1927 in Ipswich. Arrived in QLD 02.09.1864 on board the ‘Young England’ and in Ipswich the same year on board the Steamer ‘Settler’. Lived at Flint St, Nth Ipswich. Occupation: Engine Driver for QLD Government Railways. MacDonald, Robina 1865 (Drayton) B. 03.03.1865. D. 27.12.1947. Occupation: Seamstress. Married Alexander 1867 (Ipswich) approx. Fairweather. MacDonald (nee Barclay), Robina 1865 (Moreton Bay) B. 1834. D. 27.12.1908. Married to William MacDonald. Lived in Canning Street, 1865 – approx 26 Aug (Ipswich) North Ipswich. Occupation: Housewife. MacDonald, William 1865 (Moreton Bay) B. 13.04.1837. D. 26.11.1913. William lived in Canning Street, North Ipswich. 1865 – approx 26 Aug (Ipswich) Occupation: Blacksmith. MacFarlane, John 1862 (Australia) B. 1829. John established a drapery business in Ipswich. He was an Alderman of Ipswich City Council in 1873-1875, 1877-1878; Mayor of Ipswich in 1876; a member of Parliament from 1877-1894; a member of a group who established the Woollen Mill in 1875 of which he became a Director; and a member of the Ipswich Hospital Board. John MacFarlane lived at 1 Deebing Street, Denmark Hill and built a house on the corner of Waghorn and Chelmsford Avenue, Denmark Hill. -

AUSTRALIA's ORIGINAL BOYS' TOWN a Place for Change

AUSTRALIA'S ORIGINAL BOYS' TOWN A place for change... 1 2 Annual Report 2018 Page Contents 2 The Chair’s Report 3 The Executive Director’s Report 4 Summary Of Our Program 5 A Typical Day At Dunlea Centre 6 Family Engagement Manager 8 Chapel Conversion And Museum 10 Hamilton Summary 12 Savio Summary 14 Ciantar Summary 16 Fleming Summary 18 Maria Summary 20 Power Summary 22 Key Achievements In 2018 24 Staff Professional Learning And Development 26 Program Evaluation 30 Dunlea Centre Board Of Directors 32 Financials 34 Thank You 3 Chair’s Report Congratulations to Geraldine Gray who was recently appointed Chair of Dunlea Centre Board. Gerry succeeds Peter Carroll, who retired as Chair after 8 years of outstanding service. Gerry’s connections to Dunlea Centre, Australia’s Original Boys’ Town are strong and she is looking forward to leading Dunlea Centre into the future. In April 2017 Pope Francis delivered the first Papal TED The Board is very pleased that the department of Family talk (translated by TED into English) and Community Services has extended its funding of existing and new programs following their inspection in In his talk he said: August and subsequent visit in November. “To Christians, the future does have a name, and its name is In early November, I had the great pleasure of meeting Hope. Feeling hopeful does not mean to be optimistically Lori Scharff from Boys Town Omaha and am looking naive and ignore the tragedy humanity is facing. Hope is forward to hearing the staff reports following the training the virtue of a heart that doesn’t lock itself into darkness, of all agency personnel in February 2019. -

Worshipful Masters

Worshipful Masters Piddington, Albert Bathurst (1862-1945) A digital text sponsored by New South Wales Centenary of Federation Committee University of Sydney Library Sydney 2000 http://setis.library.usyd.edu.au/fed © University of Sydney Library. The texts and images are not to be used for commercial purposes without permission Source Text: Prepared from the print edition published by Angus & Robertson Limited, Sydney 1929 All quotation marks retained as data All unambiguous end-of-line hyphens have been removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to the preceding line. First Published: 1929 Languages: French Hindi German Italian Latin Greek, Classical A828.91/P/2/1 Australian Etexts biographies 1910-1939 prose nonfiction federation 2001 Creagh Cole Coordinator Final Checking and Parsing Worshipful Masters by (Mr Justice Piddington) “Gentlemen, Pray Silence! The Worshipful Master Craves the Honour of Taking Wine With You.”— Toastmaster's formula at an ancient Guild's Dinner in London. 39 Castlereagh Street, Sydney Australia: Angus & Robertson Limited 1929 To the Reader The title suggests that here you are invited to meet in surroundings of hospitality certain notable exemplars, some of life, some of mirth, some of learning, but all of human friendliness and service in their day. These worshipful masters crave the honour of taking wine with you. A.B.P. Contents CHARLES BADHAM .. .. .. .. 1 “COONAMBLE” TAYLOR .. .. .. .. 15 A TRIO IN DENMAN .. .. .. .. 36 GEORGE REID .. .. .. .. .. 53 “STORMS” PIDDINGTON .. .. .. .. 67 DADDY HALLEWELL .. .. .. .. 83 BADHAM II .. .. .. .. .. 101 SOME MASTERS IN REID'S PARLIAMENT .. .. 121 J. F. CASTLE .. .. .. .. .. /CELL> 142 BAPU GANDHI .. .. .. .. .. .. 160 SIR JULIAN SALOMONS . -

Conservation Management Plan

PHILIP LEESON ARCHITECTS Main Truss Spans Charles Dearling 2006 CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN THARWA BRIDGE for ROADS ACT by PHILIP LEESON ARCHITECTS PTY LTD ENDORSED BY THE ACT HERITAGE COUNCIL ON 5TH MARCH 2009 THARWA BRIDGE CMP MARCH 2009 PHILIP LEESON ARCHITECTS pg.1 CONTENTS PAGE 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 2.0 INTRODUCTION 3 3.0 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 6 4.0 PHYSICAL ASSESSMENT 21 5.0 ASSESSMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE 40 6.0 OPPORTUNITIES & CONSTRAINTS 44 7.0 CONSERVATION POLICIES 45 8.0 IMPLEMENTATION STRATEGIES 49 9.0 REFERENCES 55 10.0 APPENDICES 59 1 Timeline of the Murrumbidgee River Crossing 60 and Tharwa Bridge 2 Discussion of Reconstruction Proposals 78 3 Typical Cyclical Maintenance Schedule 84 4 Problems Encountered with Timber Truss Bridges 88 5 Tharwa Bridge Heritage Significance Study 95 THARWA BRIDGE CMP MARCH 2009 PHILIP LEESON ARCHITECTS pg.2 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1 This Conservation Management Plan has been prepared for Roads ACT in accordance with the conservation principles outlined in the Australia ICOMOS Burra Charter 1999. 1.2 The Plan consists of a comprehensive conservation analysis based on historical and physical overview, an assessment of cultural significance, conservation policies for the bridge and surrounds and strategies for implementation of those policies. Appendices provide a detailed chronology of historical events, a brief discussion of the heritage impact of likely proposals and a typical maintenance program. 1.3 Tharwa Bridge was listed on the ACT Heritage Register in 1998 at which time a brief assessment of significance was undertaken and a citation written. It was listed on the Register of the National Estate in 1983. -

Legislative Council

New South Wales Legislative Council PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Fifty-Seventh Parliament First Session Thursday, 24 October 2019 Authorised by the Parliament of New South Wales TABLE OF CONTENTS Visitors ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 Visitors ................................................................................................................................................... 1 Motions ...................................................................................................................................................... 1 The Hon. Shaun Leane ........................................................................................................................... 1 Bills ............................................................................................................................................................ 1 Water Supply (Critical Needs) Bill 2019 ............................................................................................... 1 First Reading ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Visitors ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 Visitors .................................................................................................................................................. -

Erley Cemetery Who's Who Law and Disorder

ERLEY CEMETERY WHO'S WHO LAW AND DISORDER COMPILED BY WAVERLEY LIBRARY 1994 :• © WAVERLEY LIBRARY ISBN 0 9588081 8 X Published by and printed at Waverley Library 14-26 Ebley Street, Bondi Junction, 2022 Telephone: (02) 389 1111 Fax: (02) 369 3306 CONTENTS Introduction 2 Index 3 Illustrated Biographies 6 Waverley Cemetery Plan 51 WAVKRI.tV CKMKTERV WHO'S wild : I AW ANI> DISORDER INTRODUCTION Waverley Cemetery opened in 1877 and now covers an area of some 41 acres, with approximately 48,000 graves and a quarter of a million burials. Waverley Council is the Trustee. Waverley Cemetery is a place for the living as well as the departed. Joggers, genealogists and visitors find interest among its headstones, paths, wildflowers and million dollar sea views. Waverley Cemetery is an open-air history lesson, a gallery of the monumental masons' art, a photographers delight, a gem for the family historian, and an open space with its own eco-system and environment. There is something for everyone. Research by Waverley library is an ongoing process to discover persons of interest buried at Waverley Cemetery. The illustrated biographies included in this booklet are only a selection of "LAW & DISORDER" personalities: Chief Justice, Supreme Court Judge, Attorney-General, Crown Solicitor, barrister, solicitor, police, murder-victim, villain, and ...the hangman. The booklet has been compiled as an accompaniment to the Waverley Library's "Waverley Cemetery: A Walk Through History, No. 6 Law and Disorder". WAVKRI.KY t'KMETERV WHO'S WHO : I .AW AND DISORDER WAVERLEY CEMETERY WHO'S WHO LAW & DISORDER NAME OCCUPATION DATE OK DEATH GRAVE SIR JOSEPH PALMER ABBOTT SOUCITOR. -

Fr Charles Jerger CP

Fr Charles Jerger CP A Passionist Priest, Interned and Deported World War 1 by Fr Gerard Mahony CP March 2008 Charles Jerger 1 Charles Jerger 2 Rt. Hon. William Morris Hughes Prime Minister of Australia – 1915 -1923 Rt Hon. Sir George Foster Pearce, Minister for Defence, 1914-1921; Acting Prime Minister 1916 Sir Ronald Munro-Ferguson Governor General of Australia Charles Jerger 3 The Germany of Charles Jerger The man who was later to join the Australian Passionists and who was expelled from this country was born in Germany. His name was Charles (or more correctly in that country Karl) Adolf Morlock. His parents were Phillip Jacob Morlock and Wilhelmina Ellenwohn, a Catholic. The date of birth on the birth certificate was 5 January 1869. He was baptised in the Evangelical faith of his father. Charles’ father was a land surveyor but Charles was to know little about him because he died the same year Charles was born. Within a year or two, another man took over the reins of the family. He was John Jerger, born at Niedereschach in Germany but since 1862-1863 he had been a British subject. The place of birth is listed as St Blasien, Baden. (Aust. Dict. Of Biography). This is in the Black Forest of Germany in the south west of the country next to France and just above Switzerland. It is a beautiful area in the diocese of Freiburg and the main activity here as in Switzerland was watch making. Pre-war Germany had a great relationship with Australia. Germany supplied migrants and also trade. -

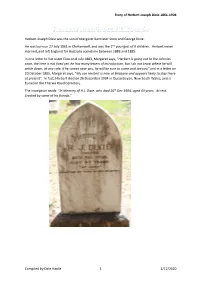

Story of Herbert Joseph Dixie 1861-1904 Compiled by Dale

Story of Herbert Joseph Dixie 1861-1904 Herbert Joseph Dixie was the son of Margaret Bannister Stow and George Dixie. He was born on 27 July 1861 in Clerkenwell, and was the 2nd youngest of 9 children. Herbert never married, and left England for Australia sometime between 1883 and 1885. In one letter to her sister Eliza on 8 July 1883, Margaret says, “Herbert is going out to the colonies soon, the time is not fixed yet, he has many letters of introduction, but I do not know where he will settle down, at any rate, if he comes near you, he will be sure to come and see you” and in a letter on 20 October 1885, Margaret says, “My son Herbert is now at Brisbane and appears likely to stay there at present”. In fact, Herbert died on 26 December 1904 in Queanbeyan, New South Wales, and is buried in the Tharwa Road Cemetery. The inscription reads: “In Memory of H.J. Dixie, who died 26th Dec 1904, aged 43 years. At rest. Erected by some of his friends.” Compiled by Dale Hartle 1 2/12/2020 Story of Herbert Joseph Dixie 1861-1904 Herbert’s lengthy and impressive Obituary was published in The Age (Queanbeyan NSW) on Friday 30 Dec 19041 and it outlines his life in Australia and the details of his death and funeral: Obituary MR HERBERT JOSEPH DIXIE Great sympathy was felt by the whole of the Queanbeyan community when, on Monday evening, flags were hoisted half-mast announcing that Alderman H. J. Dixie had passed over to the great majority. -

Undiscovered Canberra Allan J.Mortlock Bernice Anderson This Book Was Published by ANU Press Between 1965–1991

Undiscovered Canberra Allan J.Mortlock Bernice Anderson This book was published by ANU Press between 1965–1991. This republication is part of the digitisation project being carried out by Scholarly Information Services/Library and ANU Press. This project aims to make past scholarly works published by The Australian National University available to a global audience under its open-access policy. Undiscovered Canberra A collection of different places to visit, things to do and walks to take in and near Canberra. Allan J. Mortlock and Bernice Anderson 1 EDIT • A l DEPARTMENT- ■mill wi Sfiiiiiiiil U i'niiiin P-b' BLiCATlON DATE m i-H Australian National University Press, Canberra, Australia and Norwalk Conn. 1978 First published in Australia 1978 Printed in Hong Kong for the Australian National University Press, Canberra ® Allan J. Mortlockand Bernice Anderson 1978 This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism, or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Mortlock, Allan John. Undiscovered Canberra. (Canberra companions). ISBN 0 7081 1579 9. 1. Australian Capital Territory — Description and travel — Guide-books. I. Anderson, Bernice Irene, joint author. II. Title. (Series). 919.47 Library of Congress No. 78-51763 North America: Books Australia, Norwalk, Conn., USA Southeast Asia: Angus & Robertson (S.E.Asia) Pty Ltd, Singapore Japan: United Publishers Services Ltd, Tokyo Cover photograph Robert Cooper Designed by ANU Graphic Design/Adrian Young Typesetting by TypoGraphics Communications, Sydney Printed by Colorcraft, Hong Kong Introduction Visitors to Canberra, and indeed locals also, are often heard to remark that there is little to do in our national capital.