Display Inventory of the Torrent Duck

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Salvadori's Duck of New Guinea

Salvadori’s Duck of New Guinea J . K E A R When Phillips published the fourth volume of to the diving ducks and mergansers. Then his Natural History of the Ducks in 1926, he Mayr (1931a) was able to examine a dead noted that Salvadori’s Duck Salvadorina specimen and found that the sternum and (Anas) waigiuensis was ‘the last to be brought trachea of the male were, although smaller, to light and perhaps the most interesting of the similar to those of the Mallard Anas platy peculiar anatine birds of the world’. It was still rhynchos. As a result, Salvadori’s Duck was practically unknown in 1926; the first moved to the genus A nas. However, as recorded wild nest was not seen until 1959 (H. Niethammer (1952) and Kear (1972) later M. van Deusen, in litt.), and even today the pointed out, the trachea of the Torrent and species has been little studied. Blue Duck are also Anas-like, so that, on this The first specimen was called Salvadorina character, the genera M e rg a n e tta and waigiuensis in 1894 by the Hon. Walter Hymenolaimus could also be eliminated, and Rothschild and by Dr Ernst Hartert, his all three species put with the typical dabbling curator at the Zoological Museum at Tring. ducks. The name was to honour Count Tomasso The present author had already studied the Salvadori, the Italian taxonomist who Blue Duck in New Zealand (Kear, 1972), and specialized both in waterfowl and in the birds was lucky enough to be able to watch of Papua New Guinea. -

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 2010 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 20. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The World’s Waterfowl in the 21st Century: A 200 Supplement to Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World Paul A. Johnsgard Pages xvii–xxiii: recent taxonomic changes, I have revised sev- Introduction to the Family Anatidae eral of the range maps to conform with more current information. For these updates I have Since the 978 publication of my Ducks, Geese relied largely on Kear (2005). and Swans of the World hundreds if not thou- Other important waterfowl books published sands of publications on the Anatidae have since 978 and covering the entire waterfowl appeared, making a comprehensive literature family include an identification guide to the supplement and text updating impossible. -

References.Qxd 12/14/2004 10:35 AM Page 771

Ducks_References.qxd 12/14/2004 10:35 AM Page 771 References Aarvak, T. and Øien, I.J. 1994. Dverggås Anser Adams, J.S. 1971. Black Swan at Lake Ellesmere. erythropus—en truet art i Norge. Vår Fuglefauna 17: 70–80. Wildl. Rev. 3: 23–25. Aarvak, T. and Øien, I.J. 2003. Moult and autumn Adams, P.A., Robertson, G.J. and Jones, I.L. 2000. migration of non-breeding Fennoscandian Lesser White- Time-activity budgets of Harlequin Ducks molting in fronted Geese Anser erythropus mapped by satellite the Gannet Islands, Labrador. Condor 102: 703–08. telemetry. Bird Conservation International 13: 213–226. Adrian, W.L., Spraker, T.R. and Davies, R.B. 1978. Aarvak, T., Øien, I.J. and Nagy, S. 1996. The Lesser Epornitics of aspergillosis in Mallards Anas platyrhynchos White-fronted Goose monitoring programme,Ann. Rept. in north central Colorado. J. Wildl. Dis. 14: 212–17. 1996, NOF Rappportserie, No. 7. Norwegian Ornitho- AEWA 2000. Report on the conservation status of logical Society, Klaebu. migratory waterbirds in the agreement area. Technical Series Aarvak, T., Øien, I.J., Syroechkovski Jr., E.E. and No. 1.Wetlands International,Wageningen, Netherlands. Kostadinova, I. 1997. The Lesser White-fronted Goose Afton, A.D. 1983. Male and female strategies for Monitoring Programme.Annual Report 1997. Klæbu, reproduction in Lesser Scaup. Unpubl. Ph.D. thesis. Norwegian Ornithological Society. NOF Raportserie, Univ. North Dakota, Grand Forks, US. Report no. 5-1997. Afton, A.D. 1984. Influence of age and time on Abbott, C.C. 1861. Notes on the birds of the Falkland reproductive performance of female Lesser Scaup. -

Engelsk Register

Danske navne på alverdens FUGLE ENGELSK REGISTER 1 Bearbejdning af paginering og sortering af registret er foretaget ved hjælp af Microsoft Excel, hvor det har været nødvendigt at indlede sidehenvisningerne med et bogstav og eventuelt 0 for siderne 1 til 99. Tallet efter bindestregen giver artens rækkefølge på siden. -

Tribe Merganettini (Torrent Duck)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard Papers in the Biological Sciences 2010 Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Tribe Merganettini (Torrent Duck) Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World: Tribe Merganettini (Torrent Duck)" (2010). Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard. 11. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciducksgeeseswans/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ducks, Geese, and Swans of the World by Paul A. Johnsgard by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Tribe Merganettini (Torrent Duck) h4~~61. Breeding or residential distributions of the Colom- bian ("C") Peruvian ("I"'), and Argentine ("A") torrent ducks. Drawing on preceding page: Peruvian Torrent Duck body, and a contrasting rusty brown on the flanks Torrent Duck and underside of the head, neck, and body. The tail Merganetta armata Gould 1841 and wing patterns are like those of the male, as are the soft-part colors. Juveniles are generally grayish Other vernacular names. None in general English above and white below, with distinctive gray bar use. Sturzbachente (German); canard de torrents ring on the flanks. (French), pato corta-corrientes (Spanish). In the field, torrent ducks are the only waterfowl that inhabit the turbulent Andean streams, and are Subspecies and ranges. -

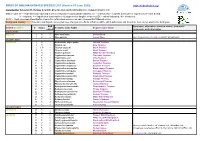

BIRDS of BOLIVIA UPDATED SPECIES LIST (Version 03 June 2020) Compiled By: Sebastian K

BIRDS OF BOLIVIA UPDATED SPECIES LIST (Version 03 June 2020) https://birdsofbolivia.org/ Compiled by: Sebastian K. Herzog, Scientific Director, Asociación Armonía ([email protected]) Status codes: R = residents known/expected to breed in Bolivia (includes partial migrants); (e) = endemic; NB = migrants not known or expected to breed in Bolivia; V = vagrants; H = hypothetical (observations not supported by tangible evidence); EX = extinct/extirpated; IN = introduced SACC = South American Classification Committee (http://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCBaseline.htm) Background shading = Scientific and English names that have changed since Birds of Bolivia (2016, 2019) publication and thus differ from names used in the field guide BoB Synonyms, alternative common names, taxonomic ORDER / FAMILY # Status Scientific name SACC English name SACC plate # comments, and other notes RHEIFORMES RHEIDAE 1 R 5 Rhea americana Greater Rhea 2 R 5 Rhea pennata Lesser Rhea Rhea tarapacensis , Puna Rhea (BirdLife International) TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE 3 R 1 Nothocercus nigrocapillus Hooded Tinamou 4 R 1 Tinamus tao Gray Tinamou 5 H, R 1 Tinamus osgoodi Black Tinamou 6 R 1 Tinamus major Great Tinamou 7 R 1 Tinamus guttatus White-throated Tinamou 8 R 1 Crypturellus cinereus Cinereous Tinamou 9 R 2 Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou 10 R 2 Crypturellus obsoletus Brown Tinamou 11 R 1 Crypturellus undulatus Undulated Tinamou 12 R 2 Crypturellus strigulosus Brazilian Tinamou 13 R 1 Crypturellus atrocapillus Black-capped Tinamou 14 R 2 Crypturellus variegatus -

The Mountain Tapir, Endangered 'Flagship' Species of the High Andes

ORYX VOL 30 NO 1 JANUARY 1996 The mountain tapir, endangered 'flagship' species of the high Andes Craig C. Downer The mountain tapir has already disappeared from parts of its range in the high Andes of South America and remaining populations are severely threatened by hunting and habitat destruction. With an estimated population of fewer than 2500 individuals, urgent measures are necessary to secure a future for the species. This paper presents an overview of the species throughout its range as well as some of the main results of the author's studies on tapir ecology. Finally, a plea is made for conservation action in Sangay National Park, which is one of the species's main strongholds. The mountain tapir: an overview throughout its range. There is limited evi- dence to indicate that it may have occurred in The mountain tapir Tapirus pinchaque, was dis- western Venezuela about 20 years ago. covered by the French naturalist Roulin near However, Venezuelan authorities indicate a Sumapaz in the eastern Andes of Colombia total absence of mountain tapir remains from (Cuvier, 1829). The species is poorly known Venezuelan territory, either from the recent or and most information has come from oc- distant past (J. Paucar, F. Bisbal, O. Linares, casional observations or captures in the wild, pers. comms). Northern Peru contains only a reports from indigenous people in the small population (Grimwood, 1969). species's range, and observations and studies In common with many montane forests in zoological parks (Cuvier, 1829; Cabrera and world-wide, those of the Andes are being Yepes, 1940; Hershkovitz, 1954; Schauenberg, rapidly destroyed, causing the decline of the 1969; Bonney and Crotty, 1979). -

Plumages and Wing Spurs of Torrent Ducks Merganetta Armata

Torrent Ducks 33 Plumages and wing spurs of Torrent Ducks Merganetta arm ata M ILTO N W. W ELLER i Introduction Because of the difficulties of studying The Torrent Duck Merganetta armata of this species in the wild or in keeping the Andean highlands is one of the most captive birds, an attempt has been made colourful and intriguing of all species of here to utilize the specimens collected by waterfowl. It has adapted to the demand scientists and professional collectors ing environment of cascading mountain throughout the Andes. Pooling data from torrents, and only rarely is seen in high these museum specimens permits the land lakes. Taxonomically, the species has biologist to visualize and even quantify been a puzzle, and Johnsgard (1966) has many of the major patterns before recently reviewed its biology and tax attempting to solve problems in the field. onomy. Both he and Delacour (1956) Such museum study is still impossible recognize only one species but differ with rarer species and at one time would in the number of races accepted. Sub have been difficult for Torrent Ducks. specific names here refer to Delacour’s However, there is now an excellent col terms which were based on Conover’s lection in the American Museum of (1943) classification and which are re Natural History and an especially fine corded on most museum specimens. series of young birds in the Conover My own experience with the species in Collection at the Field Museum of life is restricted to observations of several Natural History in Chicago. The sequence pairs in Chile (Curico Province) and ob of plumages was studied mostly from the servation of its habitat in northern Pata latter collection but nearly 200 skins were gonia (Provinces of Rio Negro and Neu- examined in museums in the eastern quen) and sub-tropical Argentina (Pro United States. -

The Taxonomy of the Anatidae—A Behavioural Analysis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UNL | Libraries University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Paul Johnsgard Collection Papers in the Biological Sciences 1-1961 The Taxonomy of the Anatidae—A Behavioural Analysis Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska–Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "The Taxonomy of the Anatidae—A Behavioural Analysis" (1961). Paul Johnsgard Collection. 29. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard/29 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Paul Johnsgard Collection by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in THE IBIS 103a:1 (January 1961), pp. 71-85. Published by British Ornithologists' Union. 1961 P. A. JOHNSGARD : BEHAVIOURAL ANALYSIS OF ANATIDAl! 71 THE TAXONOMY OF THE ANATIDAE-A BEHAVIOURAL ANALYSIS P. A. JOHNSGARD Received on 14 May 1960 Delacour & Mayr's (1945) classic revision of the Anatidae took waterfowl behaviour into account to a much larger degree than had any previous classifications of the group. However, their utilization of behavi~>ur was primarily at the tribal and generic levels, and no real attempt was made to :use behaviour for det!!rmining intrageneric relationships. Thus far only Lorenz (1941, 1951-1953) has seriously attempteq this with waterfowl, and his analysis of the relatiOnShips within the genus Anas (sensu De1acour & Mayr) has provided a remarkable insight into the evolution of this group. -

Paul Johnsgard: Comprehensive Vita and Bibliography

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers in Ornithology Papers in the Biological Sciences 1-31-2020 Paul Johnsgard: Comprehensive Vita and Bibliography Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciornithology Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Paul Johnsgard: Comprehensive Vita and Bibliography" (2020). Papers in Ornithology. 25. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciornithology/25 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in Ornithology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Paul A. Johnsgard Foundation Regents Professor Emeritus School of Biological Sciences Office: (402) 472-2728 University of Nebraska-Lincoln Fax: (402) 472-2083 Lincoln, Ne 68588-0118 email: [email protected] websites: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard/ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Johnsgard https://nebraskaauthors.org/authors/paul-a-johnsgard Professional Experience B. S. (Zoology) 1953 North Dakota State University M.S. (Wildlife Management) 1955 Washington State University Ph.D. (Vertebrate Zoology) 1959 Cornell University Postdoctoral Fellow (N.S.F. & N.I.H) 1959-61 Bristol University (England) Instructor 1961-62 Dept. of Zoology, UN-L Assistant Professor (with tenure) 1962-65 Dept. of Zoology, UN-L Associate Professor 1965-68 Dept. of Zool. & Physiol., UN-L Professor 1968-1980 School of Biological Sciences, UN-L Foundation Regents Professor 1980-2001 School of Biological Sciences, UN-L Foundation Regents Prof. Emeritus 2001-present School of Biological Sciences, UN-L Professional Recognition & Awards Listed in American Men & Women of Science, Who’s Who in the Midwest, Contemporary Authors, The Writer’s Directory, Who’s Who in Frontier Science and Technology, etc. -

ANSERIFORMES Taxon Advisory Group Regional Collection Plan 3Rd Edition • 2020 - 2025

ANSERIFORMES Taxon Advisory Group Regional Collection Plan 3rd Edition • 2020 - 2025 Edited by Photo by Pinola Conservancy Keith Lovett, Anseriformes TAG Chair Buttonwood Park Zoo Table of Contents Acknowledgements 03 TAG Operational Structure 04 TAG Steering Committee and Advisors: Table 1 05 TAG Definition 06 TAG Mission 06 TAG Vision 06 TAG Strategic Planning Overview 07 TAG Goals Sustainability 08 Conservation 09 Husbandry and Welfare 09 Educational Waterfowl Awareness and Program Support 10 TAG Taxonomy 11 TAG Taxonomy: Table 2 12 Conservation Status of Anseriformes Overview 13 Conservation Status of Anseriformes: Table 3 14 RCP History and Program Designation Program Management Designation 20 Additional Management Designation 21 Selection Criteria Selection Criteria Overview 22 Decision Tree Selection Criteria Categories 23 Proposed EAZA Waterfowl TAG European Endangered 24 Species Program (EEP) Species Anseriformes Decision Tree: Table 4 25 Anseriformes TAG Selection Criteria / Decision Tree: Table 5 26 Anseriformes TAG Selection Criteria / Decision Tree Summary 33 Space Assessment Space Assessment Overview 34 Space Survey Accountability:Responding Insititutions: Table 6 35 Space Survey Accountability: Non-responding Insititutions: Table 7 37 Space Survey Results and Target Size: Table 8 38 Regional Anseriformes Populations: Table 9 39 Summary Table 46 Non-Recommended Species Replacement Overview 47 Non-Recommended Species Replacement Chart: Table 11 48 Management Update: Table 12 51 SSP Five Year Goals and Essential Actions 53