Chronology of Selected Estonian Events, 1989

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Soviet Parliament: Process, Procedures and Legislative Priority Igor N

Cornell International Law Journal Volume 23 Article 4 Issue 2 Symposium 1990 New Soviet Parliament: Process, Procedures and Legislative Priority Igor N. Belousovitch Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cilj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Belousovitch, Igor N. (1990) "New Soviet Parliament: Process, Procedures and Legislative Priority," Cornell International Law Journal: Vol. 23: Iss. 2, Article 4. Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cilj/vol23/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell International Law Journal by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Igor N. Belousovitch* New Soviet Parliament: Process, Procedures and Legislative Priority When Gorbachev restructured the Soviet legislature in December 1988, the way in which Soviet laws are made began to change fundamen- tally. Since 1977, the right to initiate legislation has rested in the two chambers of the USSR Supreme Soviet and in its organs, in individual deputies of the Supreme Soviet, in the USSR Council of Ministers, and in various state agencies and public organizations.' In practice, how- ever, ministerial-level agencies have played the principal role in the leg- islative process. Working groups, consisting of invited academics (e.g., economists, jurists, and scientists) and practical specialists (ministerial officials and others with a direct interest in the proposed legislation), would form within- the bureaucracy for the purpose of preparing initial drafts. 2 The working draft would then move through bureaucratic chan- nels for coordination and clearance by interested agencies, and eventu- ally reach the USSR Council of Ministers for final approval and presentation to the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet (the "Presidium"). -

Download Download

Ajalooline Ajakiri, 2016, 3/4 (157/158), 477–511 Historical consciousness, personal life experiences and the orientation of Estonian foreign policy toward the West, 1988–1991 Kaarel Piirimäe and Pertti Grönholm ABSTRACT The years 1988 to 1991 were a critical juncture in the history of Estonia. Crucial steps were taken during this time to assure that Estonian foreign policy would not be directed toward the East but primarily toward the integration with the West. In times of uncertainty and institutional flux, strong individuals with ideational power matter the most. This article examines the influence of For- eign Minister Lennart Meri’s and Prime Minister Edgar Savisaar’s experienc- es and historical consciousness on their visions of Estonia’s future position in international affairs. Life stories help understand differences in their horizons of expectation, and their choices in conducting Estonian diplomacy. Keywords: historical imagination, critical junctures, foreign policy analysis, So- viet Union, Baltic states, Lennart Meri Much has been written about the Baltic states’ success in breaking away from Eastern Europe after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, and their decisive “return to the West”1 via radical economic, social and politi- Research for this article was supported by the “Reimagining Futures in the European North at the End of the Cold War” project which was financed by the Academy of Finland. Funding was also obtained from the “Estonia, the Baltic states and the Collapse of the Soviet Union: New Perspectives on the End of the Cold War” project, financed by the Estonian Research Council, and the “Myths, Cultural Tools and Functions – Historical Narratives in Constructing and Consolidating National Identity in 20th and 21st Century Estonia” project, which was financed by the Turku Institute for Advanced Studies (TIAS, University of Turku). -

Municipal Clerks and Phone Numbers

MUNICIPAL CLERKS/ADMINISTRATORS MUNICIPALITY NAME PHONE ADDRESS: HOME and/or HALL * NMD (No Mail Delivery) Town of Bangor Louisa Peterson 608-461-0554 W1250 County Rd U, Bangor WI 54614 (home) Town of Barre Ann Schlimgen 608-786-4382 N3290 Russlan Coulee Rd, La Crosse WI (home) 54601 (home) W3541 County Rd M, La Crosse WI 54601 (hall) Town of Burns Melissa Hart- 608-385-5436 W2295 E. Olson Rd, Bangor WI 54614 Pollock (home) 608-486-4272 W1313 Jewett Rd, Bangor WI 54614 (hall) (hall) Town of Cassie Hanan 608-783-0050 2219 Bainbridge St, La Crosse WI 54603 Campbell (hall) Town Hall Hours (M-F: 8-5) Town of Crystal Sbraggia 608-780-4778 PO Box 115 Mindoro, WI 54644 Farmington (cell) 608-857-3913 N8309 State Rd 108, Mindoro WI * NMD (hall) Town of Jill Murphy 608-787-0400 N1800 Town Hall Rd, La Crosse WI 54601 Greenfield (hall) (hall) 608-769-4138 (cell) Town of Sara Schultz 608-786-1516 W3501 Pleasant Valley Rd, West Salem WI Hamilton (home) 54669 608-786-0989 (hall) N5105 N Leonard St, West Salem WI 54669 (hall) Town of Marilyn Pedretti 608-526-3354 W7937 County Rd MH, Holmen WI 54636 Holland (hall) 608-317-9698 Town Hall Hours (M & Th: 8-1, W: 3-6) (cell) Town of Diane Elsen 608-781-2275 N3393 Smith Valley Rd, La Crosse WI 54601 Medary (hall) Town Hall Hours (T 8-11; Th 3-6; Fri 8-11) Town of Mary Rinehart 608-783-4958 N5589 Commerce Rd, Onalaska WI 54650 Onalaska (hall) Town Hall Hours (M-Th 8-12; 1-5; F 8-12) Town of Shelby Fortune Weaver 608-788-1032 2800 Ward Ave, La Crosse WI 54601 (hall) Town Hall Hours(M-F: 8-4) Town of Barb 608-486-2297 -

Estonian Research Agreement a Social Agreement to Ensure the Further Development of Estonian Research and Innovation

Estonian Research Agreement A social agreement to ensure the further development of Estonian research and innovation Sharing the common belief that research, development and innovation are strategically important for the well-being of the Estonian people and sustainability of society, the parties to this agreement confirm the need to guarantee the performance of the objectives agreed upon in the Estonian Research and Development and Innovation Strategy 2014–2020 “Knowledge-Based Estonia” and undertake to commit to the achievement of these objectives. For this purpose, they agree upon the following: 1. the undersigned political parties, represented by their Chairpersons, are in favour of increasing the public funding of research, development and innovation to 1% of the gross domestic product and maintaining it at least on the same level in the future. To this end, the parties agree that it will be specified in the 2019 state budget strategy that the target level is to be reached within three years with the addition of equal funding amounts; 2. Estonian research institutions, represented by the President of the Board of Universities Estonia, an association uniting Estonian public universities, affirm that research institutions will establish the institutional arrangements required for conducting and providing further incentive for performing high quality research and cooperation between researchers and entrepreneurs; 3. Estonian researchers, represented by the President of the Estonian Academy of Sciences and the President of the Estonian Young Academy of Sciences, affirm that Estonian researchers will do their best to ensure that the resources at their disposal are used for research and development in a way that guarantees a balance between basic and applied research, with the primary focus on developing fields aimed at the advancement of the Estonian economy and society; 4. -

Green Parties and Elections to the European Parliament, 1979–2019 Green Par Elections

Chapter 1 Green Parties and Elections, 1979–2019 Green parties and elections to the European Parliament, 1979–2019 Wolfgang Rüdig Introduction The history of green parties in Europe is closely intertwined with the history of elections to the European Parliament. When the first direct elections to the European Parliament took place in June 1979, the development of green parties in Europe was still in its infancy. Only in Belgium and the UK had green parties been formed that took part in these elections; but ecological lists, which were the pre- decessors of green parties, competed in other countries. Despite not winning representation, the German Greens were particularly influ- enced by the 1979 European elections. Five years later, most partic- ipating countries had seen the formation of national green parties, and the first Green MEPs from Belgium and Germany were elected. Green parties have been represented continuously in the European Parliament since 1984. Subsequent years saw Greens from many other countries joining their Belgian and German colleagues in the Euro- pean Parliament. European elections continued to be important for party formation in new EU member countries. In the 1980s it was the South European countries (Greece, Portugal and Spain), following 4 GREENS FOR A BETTER EUROPE their successful transition to democracies, that became members. Green parties did not have a strong role in their national party systems, and European elections became an important focus for party develop- ment. In the 1990s it was the turn of Austria, Finland and Sweden to join; green parties were already well established in all three nations and provided ongoing support for Greens in the European Parliament. -

Stalin's Constitution of the USSR- December 1936

Stalin’s Constitution of the USSR Moscow, USSR December 1936 ARTICLE 1. The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics is a socialist state of workers and peasants. ARTICLE 2. The Soviets of Working People's Deputies, which grew and attained strength as a result of the overthrow of the landlords and capitalists and the achievement of the dictatorship of the proletariat, constitute the political foundation of the U.S.S.R. ARTICLE 3. In the U.S.S.R. all power belongs to the working people of town and country as represented by the Soviets of Working People's Deputies. ARTICLE 4. The socialist system of economy and the socialist ownership of the means and instruments of production firmly established as a result of the abolition of the capitalist system of economy, the abrogation of private ownership of the means and instruments of production and the abolition of the exploitation of man by man, constitute' the economic foundation of the U.S.S.R. ARTICLE 5. Socialist property in the U.S.S.R. exists either in the form of state property (the possession of the whole people), or in the form of cooperative and collective-farm property (property of a collective farm or property of a cooperative association). ARTICLE 6. The land, its natural deposits, waters, forests, mills, factories, mines, rail, water and air transport, banks, post, telegraph and telephones, large state-organized agricultural enterprises (state farms, machine and tractor stations and the like) as well as municipal enterprises and the bulk of the dwelling houses in the cities and industrial localities, are state property, that is, belong to the whole people. -

Codebook Indiveu – Party Preferences

Codebook InDivEU – party preferences European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies December 2020 Introduction The “InDivEU – party preferences” dataset provides data on the positions of more than 400 parties from 28 countries1 on questions of (differentiated) European integration. The dataset comprises a selection of party positions taken from two existing datasets: (1) The EU Profiler/euandi Trend File The EU Profiler/euandi Trend File contains party positions for three rounds of European Parliament elections (2009, 2014, and 2019). Party positions were determined in an iterative process of party self-placement and expert judgement. For more information: https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/65944 (2) The Chapel Hill Expert Survey The Chapel Hill Expert Survey contains party positions for the national elections most closely corresponding the European Parliament elections of 2009, 2014, 2019. Party positions were determined by expert judgement. For more information: https://www.chesdata.eu/ Three additional party positions, related to DI-specific questions, are included in the dataset. These positions were determined by experts involved in the 2019 edition of euandi after the elections took place. The inclusion of party positions in the “InDivEU – party preferences” is limited to the following issues: - General questions about the EU - Questions about EU policy - Questions about differentiated integration - Questions about party ideology 1 This includes all 27 member states of the European Union in 2020, plus the United Kingdom. How to Cite When using the ‘InDivEU – Party Preferences’ dataset, please cite all of the following three articles: 1. Reiljan, Andres, Frederico Ferreira da Silva, Lorenzo Cicchi, Diego Garzia, Alexander H. -

Preoccupied by the Past

© Scandia 2010 http://www.tidskriftenscandia.se/ Preoccupied by the Past The Case of Estonian’s Museum of Occupations Stuart Burch & Ulf Zander The nation is born out of the resistance, ideally without external aid, of its nascent citizens against oppression […] An effective founding struggle should contain memorable massacres, atrocities, assassina- tions and the like, which serve to unite and strengthen resistance and render the resulting victory the more justified and the more fulfilling. They also can provide a focus for a ”remember the x atrocity” histori- cal narrative.1 That a ”foundation struggle mythology” can form a compelling element of national identity is eminently illustrated by the case of Estonia. Its path to independence in 98 followed by German and Soviet occupation in the Second World War and subsequent incorporation into the Soviet Union is officially presented as a period of continuous struggle, culminating in the resumption of autonomy in 99. A key institution for narrating Estonia’s particular ”foundation struggle mythology” is the Museum of Occupations – the subject of our article – which opened in Tallinn in 2003. It conforms to an observation made by Rhiannon Mason concerning the nature of national museums. These entities, she argues, play an important role in articulating, challenging and responding to public perceptions of a nation’s histories, identities, cultures and politics. At the same time, national museums are themselves shaped by the nations within which they are located.2 The privileged role of the museum plus the potency of a ”foundation struggle mythology” accounts for the rise of museums of occupation in Estonia and other Eastern European states since 989. -

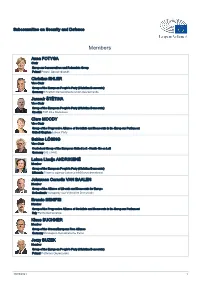

List of Members

Subcommittee on Security and Defence Members Anna FOTYGA Chair European Conservatives and Reformists Group Poland Prawo i Sprawiedliwość Christian EHLER Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Germany Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands Jaromír ŠTĚTINA Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Czechia TOP 09 a Starostové Clare MOODY Vice-Chair Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament United Kingdom Labour Party Sabine LÖSING Vice-Chair Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Germany DIE LINKE. Laima Liucija ANDRIKIENĖ Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Lithuania Tėvynės sąjunga-Lietuvos krikščionys demokratai Johannes Cornelis VAN BAALEN Member Group of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Netherlands Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie Brando BENIFEI Member Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Italy Partito Democratico Klaus BUCHNER Member Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance Germany Ökologisch-Demokratische Partei Jerzy BUZEK Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Poland Platforma Obywatelska 30/09/2021 1 Aymeric CHAUPRADE Member Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy Group France Les Français Libres Javier COUSO PERMUY Member Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Spain Independiente Arnaud DANJEAN Member Group of the European People's Party -

FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS in the SOVIET UNION: a COMPARATIVE APPROACH * T~Omas E

1967] FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS IN THE SOVIET UNION: A COMPARATIVE APPROACH * T~omAs E. TowE t INTRODUCTION The Soviet Constitution guarantees many of the same funda- mental rights as are guaranteed in the Constitution of the United States, plus several others as well. Indeed, these rights are described in greater detail and appear on their face to be safeguarded more emphatically in the Soviet Constitution. However, the mere existence of constitutional provisions for fundamental rights does not necessarily guarantee that those rights will be protected. Western scholars often point to discrepancies between rhetorical phrases in the Soviet Con- stitution and actual practices in the area of fundamental rights.' Soviet legal scholars insist, however, that such criticism should be aimed instead at Western constitutions. Andrei Vyshinsky has stated that it is precisely in the area of fundamental rights that "the contra- dictions between reality and the rights proclaimed by the bourgeois constitutions [are] particularly sharp." 2 Soviet legal scholars claim that bourgeois laws are replete with reservations and loopholes which largely negate their effectiveness in protecting fundamental rights generally, and those of the working man in particular.3 There is undoubtedly some truth in both claims, for, as Professor Berman has stated, "The striking fact is that in the protection of human rights, the Soviet system is strong where ours is weak, just as it is weak where ours is strong." 4 The full impact of this statement can only be understood by comparing the different approaches which * The author wishes to acknowledge the helpful comments and suggestions of Dr. Branko M. -

London School of Economics and Political Science Department of Government

London School of Economics and Political Science Department of Government Historical Culture, Conflicting Memories and Identities in post-Soviet Estonia Meike Wulf Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD at the University of London London 2005 UMI Number: U213073 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U213073 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Ih c s e s . r. 3 5 o ^ . Library British Library of Political and Economic Science Abstract This study investigates the interplay of collective memories and national identity in Estonia, and uses life story interviews with members of the intellectual elite as the primary source. I view collective memory not as a monolithic homogenous unit, but as subdivided into various group memories that can be conflicting. The conflict line between ‘Estonian victims’ and ‘Russian perpetrators* figures prominently in the historical culture of post-Soviet Estonia. However, by setting an ethnic Estonian memory against a ‘Soviet Russian’ memory, the official historical narrative fails to account for the complexity of the various counter-histories and newly emerging identities activated in times of socio-political ‘transition’. -

Separatist Versus Centrist Forces in the Ussr, 1988-1991: Explaining the Collapse of the Soviet Internal Empire by a Strategic Alliance Approach

********************************************************* SEPARATIST VERSUS CENTRIST FORCES IN THE USSR, 1988-1991: EXPLAINING THE COLLAPSE OF THE SOVIET INTERNAL EMPIRE BY A STRATEGIC ALLIANCE APPROACH COMPARING THE BALTIC AND THE TRANSCAUCASIAN CASES: A PROGRESS REPORT By Caspar ten Dam ********************************************************* Seminar “Soviet Internal Empire: Establishment, Daily Working and Dissolution”, by Prof. Mette Skak ERASMUS, st.nr.923488 September 1993 Reproduced & proofread for publication: March 2015 CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION: Determinism within Sovietology and Why a Strategic Alliance Approach is Chosen 4 CHAPTER 1: Aspects of Strategic Alliance 8 1.1. Alignments and Realignments among Centrist and Separatist Forces, and Types of Organization 8 1.2. Typologies of Political Groups, based on the Centrist-Separatist Divide 9 CHAPTER 2. The Baltics: Successful Separatism by Moderate Senior-Junior Partnership Alliances between the Popular Fronts and the Republican Communist Parties 14 2.1. 1988: the establishments of the Popular Fronts - and Different Degrees of Cooperation with the Communist Parties 14 2.2. 1989: the Establishments of Moderate Alliances between the Popular Fronts and the Communist Parties, and the Rising Challenges of the Radical Congress Movements 17 2.3. 1990: the Moderate/Radical CP-PF Alliances fared Differently in each Republic, and the Radical Congress Alliances had Different Rates of Success 21 2.4. 1991: the Year of Allying Dangerously 25 2.5. Conclusion 30 CHAPTER 3. The Transcaucasus: Successful Ethnonationalism and Weak Separatism by Extremist Antagonistic Blocs 32 3.1. 1988: the Establishment of Nationalist Movements against the Wishes of Conservative-Reactionary Elites 32 3.2. 1989: the Rise of Extremist Nationalism, Superseding Statist Separatism, and the Failure to Establish Strategic Alliances among the Communist Parties and Opposition Movements 36 3.3.