Volume 12 Issue 1 Sustainable Development Law & Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ch. 17.4 the Cold War Divides the World I. Fighting for the Third World A

Ch. 17.4 The Cold War Divides the World I. Fighting for the Third World A. Cold War Strategies 1. Third World countries are economically poor and unstable 2. These countries are in need of a political and economic system in which to build upon; Soviet style Communism and U.S. style free market democracy A. Cold War Strategies 3. U.S. (CIA) and Soviet (KGB) intelligence agencies engaged in covert activities 4. Both countries would provide aid to countries for loyalty to their ideology B. Association of Nonaligned Nations 1. Nonaligned nations were 3rd World nations that wanted to maintain their independence from the U.S. and Soviet influence 2. India and Indonesia were able to maintain neutrality but most took sides II. Confrontations in Latin America A. Latin America 1. The economic gap between rich and poor began to push Latin America to seek aid from both the Soviets and U.S. 2. American businesses backed leaders that protected their interests but these leaders usually oppressed their citizens A. Latin America 3. Revolutionary movements begin in Latin America and the Soviets and U.S. begin to lend support to their respective sides B. Fidel Castro and the Cuban Revolution 1. Fidel Castro led a popular revolution vs. the U.S. supported dictator Fulgencio Batista in January 1959 2. He was praised at first for bringing social reforms and improving the economy 3. But then he suspended elections, jailed and executed opponents & controlled the press B. Fidel Castro and the Cuban Revolution 4. Castro nationalized the economy taking over U.S. -

Nicaragua: in Brief

Nicaragua: In Brief Maureen Taft-Morales Specialist in Latin American Affairs September 14, 2016 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R44560 Nicaragua: In Brief Summary This report discusses Nicaragua’s current politics, economic development and relations with the United States and provides context for Nicaragua’s controversial November 6, 2016, elections. After its civil war ended, Nicaragua began to establish a democratic government in the early 1990s. Its institutions remained weak, however, and they have become increasingly politicized since the late 1990s. Current President Daniel Ortega was a Sandinista (Frente Sandinista de Liberacion Nacional, FSLN) leader when the Sandinistas overthrew the dictatorship of Anastasio Somoza in 1979. Ortega was elected president in 1984. An electorate weary of war between the government and U.S.-backed contras denied him reelection in 1990. After three failed attempts, he won reelection in 2006, and again in 2011. He is expected to win a third term in November 2016 presidential elections. As in local, municipal, and national elections in recent years, the legitimacy of this election process is in question, especially after Ortega declared that no domestic or international observers would be allowed to monitor the elections and an opposition coalition was effectively barred from running in the 2016 elections. As a leader of the opposition in the legislature from 1990 to 2006, and as president since then, Ortega slowly consolidated Sandinista—and personal—control over Nicaraguan institutions. As Ortega has gained power, he reputedly has become one of the country’s wealthiest men. His family’s wealth and influence have grown as well, inviting comparisons to the Somoza family dictatorship. -

Fondation Pierre Du Bois | Ch

N°2 | February 2021 Structures of Genocide: Making Sense of the New War for Nagorno-Karabakh Joel Veldkamp * “Terrorists we’re fighting and we’re never gonna stop The prostitutes who prosecute have failed us from the start Can you see us?” - System of a Down, “Genocidal Humanoidz” On December 10, 2020, Turkey and Azerbaijan held a joint victory parade in Azerbaijan’s capital of Baku. Turkey’s president Tayyib Recep Erdogan and Azerbaijan’s president Ilham Aliyev stood together on a dais in front of twenty Turkish and Azerbaijani flags, as 3,000 members of the Azerbaijani Armed Forces marched by, displaying military hardware captured from their Armenian foes. Military bands played the anthems of the old Ottoman Empire, the Turkish dynasty that ruled much of the Middle East in the name of Islam until World War I. Azerbaijani jets roared over the capital, dropping smoke in the green, blue and red colors of the Azerbaijani flag. Certainly, there was much to celebrate. In forty-four days of brutal combat, Azerbaijani forces reversed the humiliating defeat they experienced at Armenia’s hands in 1994 and recaptured much of the disputed territory of Nagorno-Karabakh. Turkey worked with Azerbaijan hand-in-glove during the war, supplying it with weapons, providing intelligence and air support, and bringing in thousands of battle-hardened fighters from Syria to fight on the ground.1 The victory opened up the possibility that the hundreds of thousands of Azerbaijanis driven from Armenian-occupied territory in the first Karabakh war, many of whom had lived for decades in squalid camps in Baku and its environs, would be able to go home.2 It was an impressive vindication of the alliance of these two Turkish states, exemplifying their alliance’s motto, “two states, one nation.” But a darker spirit was on display during the parade. -

Fidel Castro Calls Lor Solidarity Wnh Nicaragua

AUGUST 24, 1979 25 CENTS VOLUME 43/NUMBER 32 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE Carter stalls aid, seeks to strangle freedom fi9ht -- Mit;t.. ntll=rArl MANA~UA, August 3-Thousands of Nicaraguans from working-class and poor neighborhoods rally in support of revolution. on-the-scene reports Fidel castro -Workers & peasants calls lor rebuild country -PAGE 2 ·Sandinista leader appeals SOlidaritY for support -PAGE 16 wnh Nicaragua ~Statement by Full text-Pages 10-14 Fourth International-PAGE 6 In face of U.S. imP-erialist threat orkers and peasants By Pedro Camejo, Sergio Rodriguez and Fred Murphy MANAGUA, Nicaragua-The social ist revolution has begun in Nicaragua. Under the leadership of the Sandi nista National Liberation Front, the workers and peasants have over thrown the imperialist-backed Somoza dictatorship and destroyed its army and police force. Basing itself on the power of the armed and mobilized masses, the San dinista leadership has begun taking a series of radical measures-a deepgo ing land reform, nationalization of all the country's banks, seizure of all the property held by the Somoza family and its collaborators, the formation of popular militias and a revolutionary Pedro Camejo, a leader of the Socialist Workers Party, and Sergio Rodriguez, a leader of the Revolu tionary Workers Party of Mexico, went to Nicaragua to gather first hand information for the United Secretariat of the Fourth Interna tional, the world Trotskyist organi Victorious Nicaraguans drag statue of Somoza's father through streets of Managua zation, and for Trotskyists around the world. -

Failed Or Fragile States in International Power Politics

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2013 Failed or Fragile States in International Power Politics Nussrathullah W. Said CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/171 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Failed or Fragile States in International Power Politics Nussrathullah W. Said May 2013 Master’s Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of International Affairs at the City College of New York Advisor: Dr. Jean Krasno This thesis is dedicated to Karl Markl, an important member of my life who supported me throughout my college endeavor. Thank you Karl Markl 1 Contents Part I Chapter 1 – Introduction: Theoretical Framework………………………………1 The importance of the Issue………………………………………….6 Research Design………………………………………………………8 Methodology/Direction……………………………………………….9 Chapter 2 – Definition and Literature…………………………………………….10 Part II Chapter 3 – What is a Failed State? ......................................................................22 Chapter 4 – What Causes State Failure? ..............................................................31 Part III Chapter 5 – The Case of Somalia…………………………………………………..41 Chapter 6 – The Case of Yemen……………………………………………………50 Chapter 7 – The Case of Afghanistan……………………………………………...59 Who are the Taliban? …………………………………………….....66 Part IV Chapter 8 – Analysis………………………………………………………………79 Chapter 9 – Conclusion……………………………………………………………89 Policy Recommendations…………………………………………….93 Bibliography…………………………………………………….........95 2 Abstract The problem of failed states, countries that face chaos and anarchy within their border, is a growing challenge to the international community especially since September 11, 2001. -

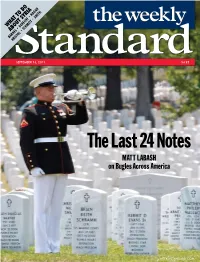

The Last 24 Notes MATT LABASH on Bugles Across America

WHAT TO DO ABOUT SYRIA BARNES • GERECHT • KAGAN KRISTOL • SCHMITT • SMITH SEPTEMBER 16, 2013 $4.95 The Last 24 Notes MATT LABASH on Bugles Across America WWEEKLYSTANDARD.COMEEKLYSTANDARD.COM Contents September 16, 2013 • Volume 19, Number 2 2 The Scrapbook We’ll take the disposable Post, the march of science, & more 5 Casual Joseph Bottum gets stuck in the land of honey 7 Editorial The Right Vote BY WILLIAM KRISTOL Articles 9 I Came, I Saw, I Skedaddled BY P. J. O’ROURKE Decisive moments in Barack Obama history 7 10 Do It for the Presidency BY GARY SCHMITT Congress, this time at least, shouldn’t say no to Obama 12 What to Do About Syria BY FREDERICK W. K AGAN Vital U.S. interests are at stake 14 Sorting Out the Opposition to Assad BY LEE SMITH They’re not all jihadist dead-enders 16 Hesitation, Delay, and Unreliability BY FRED BARNES Not the qualities one looks for in a war president 17 The Louisiana GOP Gains a Convert BY MICHAEL WARREN Elbert Lee Guillory, Cajun noir Features 20 The Last 24 Notes BY MATT LABASH Tom Day and the volunteer buglers who play ‘Taps’ at veterans’ funerals across America 26 The Muddle East BY REUEL MARC GERECHT Every idea Obama had about pacifying the Muslim world turned out to be wrong Books & Arts 9 30 Winston in Focus BY ANDREW ROBERTS A great man gets a second look 32 Indivisible Man BY EDWIN M. YODER JR. Albert Murray, 1916-2013 33 Classical Revival BY MARK FALCOFF Germany breaks from its past to embrace the past 36 Living in Vein BY JOSHUA GELERNTER Remember the man who invented modern medicine 37 With a Grain of Salt BY ELI LEHRER Who and what, exactly, is the chef du jour? 39 Still Small Voice BY JOHN PODHORETZ Sundance gives birth to yet another meh-sterpiece 20 40 Parody And in Russia, the sun revolves around us COVER: An honor guard bugler plays at the burial of U.S. -

U.S. Has More Jobs Than Jobless Chinese Companies Buying Stake in the Chinese Opera- More U.S

****** WEDNESDAY, JUNE 6, 2018 ~ VOL. CCLXXI NO. 131 WSJ.com HHHH $4.00 DJIA 24799.98 g 13.71 0.1% NASDAQ 7637.86 À 0.4% STOXX 600 386.89 g 0.3% 10-YR. TREAS. À 6/32 , yield 2.917% OIL $65.52 À $0.77 GOLD $1,297.50 À $4.40 EURO $1.1720 YEN 109.79 What’s It’s a Jungle Out There for California’s Gubernatorial Candidates Beijing News Proposes Business&Finance ADeal On Trade Job openings in the U.S. exceeded the number of China says it will buy job seekers this spring for the first time since such record- $70 billion in U.S. keeping began in 2000. A1 goods if Trump drops Facebook struck data threat of tariffs partnerships with Chinese companies, including Huawei, China offered to purchase a firm U.S. officials view as a nearly $70 billion of U.S. farm, potential tool for spying. A10 manufacturing and energy U.K. regulators approved products if the Trump admin- Comcast’s bid for Sky and istration abandons threatened gave a tentative green light tariffs, according to people to a rival offer from Fox. B1 briefed on the latest negotia- tions with American trade of- OPEC and its allies will ficials. consider China’s store of oil in deciding whether to continue By Lingling Wei in supply cuts, officials say. B1 Beijing and Bob Davis The Nasdaq rose 0.4% to in Washington 7637.86, a second consecu- CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT: K.C. ALFRED/THE SAN DIEGO UNION-TRIBUNE/AP; JUSTIN SULLIVAN/GETTY; RICHARD VOGEL/AP tive record. -

Sam Haraway Women's Movements in Revolutionary Cuba & Nicaragua

Sam Haraway Women’s Movements in Revolutionary Cuba & Nicaragua Abstract: Despite their Marxist orientation, the revolutionary struggles of the 26th of July Movement in Cuba and the Sandinista National Liberation Front in Nicaragua were quite distinct. This is particularly true in regards to the experiences of women in both revolutionary movements. This paper explores this varied experience, focusing specifically on women within the guerrilla movements, women within their political arm of the vanguard, and the effect of the socio-cultural struggle on the realization of women's advancement after the movements had assumed power. It concludes three trends: more Nicaraguan women participated directly in the revolutionary struggle (albeit for different reasons), once the movements had been institutionalized the governments pursued women's advancement only in terms of greater class concerns, and the machista norm has proven a significant barrier in the progress of both revolutions. There is little dispute over the role Marxism has played in movements for social change in Latin America. As an ideology reacting to the perceived injustices of capitalism, it seems relevant that a discussion surrounding the realization of Marx’s alternative exists in the context of two successful revolutions. Moreover, while Marxism espouses a commitment to an egalitarian society, it is interesting to examine the extent to which this has been realized for women. This paper will argue that the advancement of women under the revolutionary movements of Cuba and Nicaragua, while beginning with similar ideological commitments, were experienced and realized in distinct manners. That is, although both revolutionary governments were committed to a similar vanguard Marxism, the experience of women varied in each country, as the result of the unique environments of both states. -

Migration Crisis in Europe

Migration Crisis in Europe: Political, Socio-Economic Reasons and Challenges, Ways of Solution Journal of Social Sciences; ISSN: 2233-3878; e-ISSN: 2346-8262; Volume 5, Issue 2, 2016 Migration Crisis in Europe: Political, Socio-Economic Reasons and Challenges, Ways of Solution Aytan Merdan HAJIYEVA* Fakhri HAJIYEV** Abstract In 2015, a dramatic increase in migrant flows to Europe from the Middle East and Africa has led to a migration crisis. The main goal of the paper is to analyze the socio-econom- ic impact of the migration flows to Europe and its political consequences. The paper has found that the migration has a negative influence over the European socio-economic environment. Keywords: European migration crisis, European Union, migration, refugees, Syria war. Introduction Population mobility and migration of human masses across values and the actions of the world institutions that promote continents due to certain factors is a natural process that such ideas and values influence the growth and current has been lasting for thousands of years. Throughout the transformation of migration (Attina, 2015). history the European continent has been a vastly attractive In recent years, Arab revolts led to a rapid expansion of destination point for international immigrants. Main reasons the flow of migrants across the Mediterranean to Europe. for migration over the years were world wars, natural disas- Conflicts in the Middle East and North Africa that occurred ters, attractiveness of development of western countries, as a result of the socio-political processes have contributed etc. heavily to the refugee crisis in Europe. The United Nations As new life tendencies take place in step with the time, reported that war in Syria and Iraq, as well as continuing the migration has also grown into a different form in the violence and instability in Afghanistan, Eritrea, etc., have contemporary world. -

Intimate Bodies, Violent Struggles the Poetics And

Durham E-Theses Intimate Bodies, Violent Struggles: The poetics and politics of nuptiality in Syria KASTRINOU, A. MARIA A. How to cite: KASTRINOU, A. MARIA A. (2012) Intimate Bodies, Violent Struggles: The poetics and politics of nuptiality in Syria , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4923/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Intimate Bodies, Violent Struggles The poetics and politics of nuptiality in Syria A. Maria A. Kastrinou Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology Durham University 2012 Abstract Intimate bodies, violent struggles: The poetics and politics of nuptiality in Syria Caught between conflicting historical fantasies of an exotic Orient and images of the oppressive and threatening Other, Syria embodies both the colonial attraction of Arabesque par excellance simultaneously along with fears of civilization clashes. -

Amer Skeiker Thesis NOHA

Challenging Gender Roles within Humanitarian Crisis: Predominant Patriarchal Structures before the Humanitarian Crisis and its Relation to the Identity and Experiences of Women refugees during and after the Humanitarian Crisis. A Case Study of Syria. Written by: Amer Skeiker Supervised by: Lisbeth Larsson Lidén NOHA International Masters in Humanitarian Action Uppsala University, Sweden December: 2015 1 This thesis is submitted for obtaining the Master’s Degree in International Humanitarian Action. By submitting the thesis, the author certifies that the text is from his/her hand, does not include the work of someone else unless clearly indicated, and that the thesis has been produced in accordance with proper academic practices. 2 Abstract One purpose of this study is to examine how predominant patriarchal practices can affect the experiences of women refugees. This study also examines how the gender roles and patriarchal practices may change during a conflict. A theoretical framework was constructed to examine the patriarchal practices through radical feminism approach. Also, possible ways of social change within a conflict is examined. Empirically, the Syrian conflict is selected for the case study. In order to answer the research questions, 26 semi-structured interviews were conducted to track any possible social change in the patriarchal practices in Syria during the conflict in comparison to before the conflict. The main two findings of this study are that a change did occur in the patriarchal practices in which women did achieve more freedom and more independence during the conflict in Syria. However, there were increased patriarchal practices when women became refugees outside Syria, in which there was less freedom and less independence for Syrian women, especially the less educated women. -

The Real North Korea This Page Intentionally Left Blank the Real North Korea

The Real North Korea This page intentionally left blank The Real North Korea Life and Politics in the Failed Stalinist Utopia ANDREI LANKOV 1 1 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Th ailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries. Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 © 2013 Andrei Lankov All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lankov, A. N. (Andrei Nikolaevich) Th e real North Korea : life and politics in the failed Stalinist utopia / Andrei Lankov.