The Real North Korea This Page Intentionally Left Blank the Real North Korea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

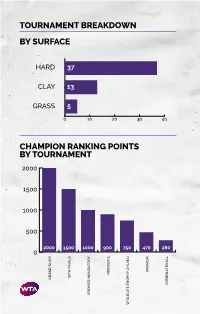

Tournament Breakdown by Surface Champion Ranking Points By

TOURNAMENT BREAKDOWN BY SURFACE HAR 37 CLAY 13 GRASS 5 0 10 20 30 40 CHAMPION RANKING POINTS BY TOURNAMENT 2000 1500 1000 500 2000 1500 1000 900 750 470 280 0 PREMIER PREMIER TA FINALS TA GRAN SLAM INTERNATIONAL PREMIER MANATORY TA ELITE TROPHY HUHAI TROPHY ELITE TA 55 WTA TOURNAMENTS BY REGION BY COUNTRY 8 CHINA 2 SPAIN 1 MOROCCO UNITED STATES 2 SWITZERLAND 7 OF AMERICA 1 NETHERLANDS 3 AUSTRALIA 1 AUSTRIA 1 NEW ZEALAND 3 GREAT BRITAIN 1 COLOMBIA 1 QATAR 3 RUSSIA 1 CZECH REPUBLIC 1 ROMANIA 2 CANADA 1 FRANCE 1 THAILAND 2 GERMANY 1 HONG KONG 1 TURKEY UNITED ARAB 2 ITALY 1 HUNGARY 1 EMIRATES 2 JAPAN 1 SOUTH KOREA 1 UZBEKISTAN 2 MEXICO 1 LUXEMBOURG TOURNAMENTS TOURNAMENTS International Tennis Federation As the world governing body of tennis, the Davis Cup by BNP Paribas and women’s Fed Cup by International Tennis Federation (ITF) is responsible for BNP Paribas are the largest annual international team every level of the sport including the regulation of competitions in sport and most prized in the ITF’s rules and the future development of the game. Based event portfolio. Both have a rich history and have in London, the ITF currently has 210 member nations consistently attracted the best players from each and six regional associations, which administer the passing generation. Further information is available at game in their respective areas, in close consultation www.daviscup.com and www.fedcup.com. with the ITF. The Olympic and Paralympic Tennis Events are also an The ITF is committed to promoting tennis around the important part of the ITF’s responsibilities, with the world and encouraging as many people as possible to 2020 events being held in Tokyo. -

CREC-2016-01-13.Pdf

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 114 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 162 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 13, 2016 No. 8 Senate The Senate was not in session today. Its next meeting will be held on Friday, January 15, 2016, at 11 a.m. House of Representatives WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 13, 2016 The House met at 9 a.m. and was Pursuant to clause 1, rule I, the Jour- tions that will get our Nation back on called to order by the Speaker. nal stands approved. track with the American people, not f f Washington bureaucrats. President Obama promised hope and PRAYER PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE change, but his failed agenda has The Chaplain, the Reverend Patrick The SPEAKER. Will the gentle- brought the wrong kind of change, and J. Conroy, offered the following prayer: woman from North Carolina (Ms. FOXX) many North Carolinians are losing We give You thanks, merciful God, come forward and lead the House in the hope. for giving us another day. Pledge of Allegiance. Fortunately, Republicans are com- As You make available to Your peo- Ms. FOXX led the Pledge of Alle- mitted to restoring confidence in ple the grace and knowledge to meet giance as follows: America and empowering her people to the needs of the day, we pray that Your I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the make their own decisions and pursue spirit will be upon the Members of this United States of America, and to the Repub- their own dreams. -

Record of North Korea's Major Conventional Provocations Since

May 25, 2010 Record of North Korea’s Major Conventional Provocations since 1960s Complied by the Office of the Korea Chair, CSIS Please note that the conventional provocations we listed herein only include major armed conflicts, military/espionage incursions, border infractions, acts of terrorism including sabotage bombings and political assassinations since the 1960s that resulted in casualties in order to analyze the significance of the attack on the Cheonan and loss of military personnel. This list excludes any North Korean verbal threats and instigation, kidnapping as well as the country’s missile launches and nuclear tests. January 21, 1968 Blue House Raid A North Korean armed guerrilla unit crossed the Demilitarized Zone into South Korea and, in disguise of South Korean military and civilians, attempted to infiltrate the Blue House to assassinate South Korean President Park Chung-hee. The assassination attempt was foiled, and in the process of pursuing commandos escaping back to North Korea, a significant number of South Korean police and soldiers were killed and wounded, allegedly as many as 68 and 66, respectively. Six American casualties were also reported. ROK Response: All 31 North Korean infiltrators were hunted down and killed except Kim Shin-Jo. After the raid, South Korea swiftly moved to strengthen the national defense by establishing the ROK Reserve Forces and defense industry and installing iron fencing along the military demarcation line. January 23, 1968 USS Pueblo Seizure The U.S. navy intelligence ship Pueblo on its mission near the coast of North Korea was captured in international waters by North Korea. Out of 83 crewmen, one died and 82 men were held prisoners for 11 months. -

North Korea-South Korea Relations: Never Mind the Nukes?

North Korea-South Korea Relations: Never Mind The Nukes? Aidan Foster-Carter Leeds University, UK Almost a year after charges that North Korea has a second, covert nuclear program plunged the Peninsula into intermittent crisis, inter-Korean ties appear surprisingly unaffected. The past quarter saw sustained and brisk exchanges on many fronts, seemingly regardless of this looming shadow. Although Pyongyang steadfastly refuses to discuss the nuclear issue with Seoul bilaterally, the fact that six-party talks on this topic were held in Beijing in late August – albeit with no tangible progress, nor even any assurance that such dialogue will continue – is perhaps taken (rightly or wrongly) as meaning the issue is now under control. At all events, between North and South Korea it is back to business as usual – or even full steam ahead. While (at least in this writer’s view) closer inter-Korean relations are in themselves a good thing, one can easily imagine scenarios in which this process may come into conflict with U.S. policy. Should the six-party process fail or break down, or if Pyongyang were to test a bomb or declare itself a nuclear power, then there would be strong pressure from Washington for sanctions in some form. Indeed, alongside the six- way process, the U.S. is already pursuing an interdiction policy with its Proliferation Security Initiative (PSI), which Japan has joined but South Korea, pointedly, has not. Relinking of cross-border roads and railways, or the planned industrial park at Kaesong (with power and water from the South), are examples of initiatives which might founder, were the political weather around the Peninsula to turn seriously chilly. -

South Korea Section 3

DEFENSE WHITE PAPER Message from the Minister of National Defense The year 2010 marked the 60th anniversary of the outbreak of the Korean War. Since the end of the war, the Republic of Korea has made such great strides and its economy now ranks among the 10-plus largest economies in the world. Out of the ashes of the war, it has risen from an aid recipient to a donor nation. Korea’s economic miracle rests on the strength and commitment of the ROK military. However, the threat of war and persistent security concerns remain undiminished on the Korean Peninsula. North Korea is threatening peace with its recent surprise attack against the ROK Ship CheonanDQGLWV¿ULQJRIDUWLOOHU\DW<HRQS\HRQJ Island. The series of illegitimate armed provocations by the North have left a fragile peace on the Korean Peninsula. Transnational and non-military threats coupled with potential conflicts among Northeast Asian countries add another element that further jeopardizes the Korean Peninsula’s security. To handle security threats, the ROK military has instituted its Defense Vision to foster an ‘Advanced Elite Military,’ which will realize the said Vision. As part of the efforts, the ROK military complemented the Defense Reform Basic Plan and has UHYDPSHGLWVZHDSRQSURFXUHPHQWDQGDFTXLVLWLRQV\VWHP,QDGGLWLRQLWKDVUHYDPSHGWKHHGXFDWLRQDOV\VWHPIRURI¿FHUVZKLOH strengthening the current training system by extending the basic training period and by taking other measures. The military has also endeavored to invigorate the defense industry as an exporter so the defense economy may develop as a new growth engine for the entire Korean economy. To reduce any possible inconveniences that Koreans may experience, the military has reformed its defense rules and regulations to ease the standards necessary to designate a Military Installation Protection Zone. -

Electoral Politics in South Korea

South Korea: Aurel Croissant Electoral Politics in South Korea Aurel Croissant Introduction In December 1997, South Korean democracy faced the fifteenth presidential elections since the Republic of Korea became independent in August 1948. For the first time in almost 50 years, elections led to a take-over of power by the opposition. Simultaneously, the election marked the tenth anniversary of Korean democracy, which successfully passed its first ‘turnover test’ (Huntington, 1991) when elected President Kim Dae-jung was inaugurated on 25 February 1998. For South Korea, which had had six constitutions in only five decades and in which no president had left office peacefully before democratization took place in 1987, the last 15 years have marked a period of unprecedented democratic continuity and political stability. Because of this, some observers already call South Korea ‘the most powerful democracy in East Asia after Japan’ (Diamond and Shin, 2000: 1). The victory of the opposition over the party in power and, above all, the turnover of the presidency in 1998 seem to indicate that Korean democracy is on the road to full consolidation (Diamond and Shin, 2000: 3). This chapter will focus on the role elections and the electoral system have played in the political development of South Korea since independence, and especially after democratization in 1987-88. Five questions structure the analysis: 1. How has the electoral system developed in South Korea since independence in 1948? 2. What functions have elections and electoral systems had in South Korea during the last five decades? 3. What have been the patterns of electoral politics and electoral reform in South Korea? 4. -

Joseonhakgyo, Learning Under North Korean Leadership: Transitioning from 1970 to Present*

https://doi.org/10.33728/ijkus.2020.29.1.007 International Journal of Korean Unification Studies Vol. 29, No. 1, 2020, 161-188. Joseonhakgyo, Learning under North Korean Leadership: Transitioning from 1970 to Present* Min Hye Cho** This paper analyzes English as a Foreign Language (EFL) textbooks used during North Korea’s three leaderships: 1970s, 1990s and present. The textbooks have been used at Korean ethnic schools, Joseonhakgyo (朝鮮学校), which are managed by the Chongryon (總聯) organization in Japan. The organization is affiliated with North Korea despite its South Korean origins. Given North Korea’s changing influence over Chongryon’s education system, this study investigates how Chongryon Koreans’ view on themselves has undergone a transition. The textbooks’ content that have been used in junior high school classrooms (students aged between thirteen and fifteen years) are analyzed. Selected texts from these textbooks are analyzed critically to delineate the changing views of Chongryon Koreans. The findings demonstrate that Chongryon Koreans have changed their perspective from focusing on their ties to North Korea (1970s) to focusing on surviving as a minority group (1990s) to finally recognising that they reside permanently in Japan (present). Keywords: EFL textbooks, Korean ethnic school, minority education, North Koreans in Japan, North Korean leadership ** Acknowledgments: The author would like to acknowledge the generous and thoughtful support of the staff at Hagusobang (Chongryon publishing company), including Mr Nam In Ryang, Ms Kyong Suk Kim and Ms Mi Ja Moon; Ms Malryo Jang, an English teacher at Joseonhakgyo; and Mr Seong Bok Kang at Joseon University in Tokyo. They have consistently provided primary resource materials, such as Chongryon EFL textbooks, which made this research project possible. -

Ch. 17.4 the Cold War Divides the World I. Fighting for the Third World A

Ch. 17.4 The Cold War Divides the World I. Fighting for the Third World A. Cold War Strategies 1. Third World countries are economically poor and unstable 2. These countries are in need of a political and economic system in which to build upon; Soviet style Communism and U.S. style free market democracy A. Cold War Strategies 3. U.S. (CIA) and Soviet (KGB) intelligence agencies engaged in covert activities 4. Both countries would provide aid to countries for loyalty to their ideology B. Association of Nonaligned Nations 1. Nonaligned nations were 3rd World nations that wanted to maintain their independence from the U.S. and Soviet influence 2. India and Indonesia were able to maintain neutrality but most took sides II. Confrontations in Latin America A. Latin America 1. The economic gap between rich and poor began to push Latin America to seek aid from both the Soviets and U.S. 2. American businesses backed leaders that protected their interests but these leaders usually oppressed their citizens A. Latin America 3. Revolutionary movements begin in Latin America and the Soviets and U.S. begin to lend support to their respective sides B. Fidel Castro and the Cuban Revolution 1. Fidel Castro led a popular revolution vs. the U.S. supported dictator Fulgencio Batista in January 1959 2. He was praised at first for bringing social reforms and improving the economy 3. But then he suspended elections, jailed and executed opponents & controlled the press B. Fidel Castro and the Cuban Revolution 4. Castro nationalized the economy taking over U.S. -

In Pueblo's Wake

IN PUEBLO’S WAKE: FLAWED LEADERSHIP AND THE ROLE OF JUCHE IN THE CAPTURE OF THE USS PUEBLO by JAMES A. DUERMEYER Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN U.S. HISTORY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON December 2016 Copyright © by James Duermeyer 2016 All Rights Reserved Acknowledgements My sincere thanks to my professor and friend, Dr. Joyce Goldberg, who has guided me in my search for the detailed and obscure facts that make a thesis more interesting to read and scholarly in content. Her advice has helped me to dig just a bit deeper than my original ideas and produce a more professional paper. Thank you, Dr. Goldberg. I also wish to thank my wife, Janet, for her patience, her editing, and sage advice. She has always been extremely supportive in my quest for the masters degree and was my source of encouragement through three years of study. Thank you, Janet. October 21, 2016 ii Abstract IN PUEBLO’S WAKE: FLAWED LEADERSHIP AND THE ROLE OF JUCHE IN THE CAPTURE OF THE USS PUEBLO James Duermeyer, MA, U.S. History The University of Texas at Arlington, 2016 Supervising Professor: Joyce Goldberg On January 23, 1968, North Korea attacked and seized an American Navy spy ship, the USS Pueblo. In the process, one American sailor was mortally wounded and another ten crew members were injured, including the ship’s commanding officer. The crew was held for eleven months in a North Korea prison. -

1972 FAMILY TAPE CODE Variable Tape Number Location Content ------1 1-3 Study Number 768 (Wave 5) (2401) (4501-4503)

1972 FAMILY TAPE CODE Variable Tape Number Location Content -------- -------- ------- 1 1-3 Study Number 768 (Wave 5) (2401) (4501-4503) ------------------------- 2 4-7 1972 Interview Number (2402) (4504-4507) --------------------- 3 8-9 *State of Residence at time of 1972 Interview (2403) (4508-4509) --------------------------------------------- 4 10-12 *County of Residence at time of 1972 Interview (2404) (4510-4512) ---------------------------------------------- 5 13-17 *State and County of Residence at time of (2405) (4513-4517) 1972 Interview ----------------------------------------- V3 and V4 combined into one variable 6 18 Size of Largest City in PSU (2406) (4518) --------------------------- 34.2 1. SMSA: largest city 500,000 or more 22.0 2. SMSA: largest city 100,000 - 499,999 11.7 3. SMSA: largest city 50,000 - 99,999 7.2 4. Non-SMSA: largest citv 25,000 - 49,999 9.5 5. Non-SMSA: largest city 10,000 - 24,999 15.1 6. Non-SMSA: largest city under 10,000 0.2 9. N.A.; DU is not in continental U.S.A. ----- 99.9 7 19 Color of Coversheet (2407) (4519) ------------------- 75.0 0. Brown (Main Family) 3.0 1. Yellow (Split-off) 20.0 2. Blue (Main Family) 2.0 3. Pink (Split-off) ----- 100.0 * Detailed State and County Codes will be furnished on request 8 20 Whether Originally Refused in 1972 A variable (2408) (4520) to determine whether or not the respondent at first refused to be interviewed this year --------------------------------------------- 99.8 0. Never refused 0.2 1. Refused at least once 0.0 9. N.A. ----- 100.0 9 21 Whether Telephone Interview in 1972 (2409) (4521) ----------------------------------- 97.2 0. -

Military Transformation on the Korean Peninsula: Technology Versus Geography

THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL Military Transformation on the Korean Peninsula: Technology Versus Geography Being a Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy At the University of Hull By Soon Ho Lee BA, Sungkyunkwan University, Republic of Korea, 2004 MA, The University of Birmingham, United Kingdom, 2005 MRes, King’s College London, United Kingdom, 2006 1 Acknowledgement I am the most grateful to my Supervisor Dr. David Lonsdale for his valuable academic advice and support during the long PhD journey. To reach this stage, I have had invaluable support from my family back in Korea and my dear wife Jin Heon. I would also like to thank my family for being so patient while I was researching. During this journey, I have obtained a precious jewel in my daughter, Da Hyeon. I will pray for you all my life. I would like to give special thanks to my late grandfather who gave me the greatest love, and taught me the importance of family. 2 Thesis Summary This thesis provides an explanation of one RMA issue: the effectiveness of contemporary military technology against tough geography, based upon case studies in the Korean peninsula. The originality of the thesis is that it will provide a sound insight for potential foes’ approach to the dominant US military power (superior technology and sustenance of war). The North Korean defence strategy – using their edge in geography and skill – tried to protect themselves from the dominant US power, but it may be impossible to deter or defeat them with technological superiority alone. -

Nicaragua: in Brief

Nicaragua: In Brief Maureen Taft-Morales Specialist in Latin American Affairs September 14, 2016 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R44560 Nicaragua: In Brief Summary This report discusses Nicaragua’s current politics, economic development and relations with the United States and provides context for Nicaragua’s controversial November 6, 2016, elections. After its civil war ended, Nicaragua began to establish a democratic government in the early 1990s. Its institutions remained weak, however, and they have become increasingly politicized since the late 1990s. Current President Daniel Ortega was a Sandinista (Frente Sandinista de Liberacion Nacional, FSLN) leader when the Sandinistas overthrew the dictatorship of Anastasio Somoza in 1979. Ortega was elected president in 1984. An electorate weary of war between the government and U.S.-backed contras denied him reelection in 1990. After three failed attempts, he won reelection in 2006, and again in 2011. He is expected to win a third term in November 2016 presidential elections. As in local, municipal, and national elections in recent years, the legitimacy of this election process is in question, especially after Ortega declared that no domestic or international observers would be allowed to monitor the elections and an opposition coalition was effectively barred from running in the 2016 elections. As a leader of the opposition in the legislature from 1990 to 2006, and as president since then, Ortega slowly consolidated Sandinista—and personal—control over Nicaraguan institutions. As Ortega has gained power, he reputedly has become one of the country’s wealthiest men. His family’s wealth and influence have grown as well, inviting comparisons to the Somoza family dictatorship.