Fondation Pierre Du Bois | Ch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020)

Record Store Day 2020 (GSA) - 18.04.2020 | (Stand: 05.03.2020) Vertrieb Interpret Titel Info Format Inhalt Label Genre Artikelnummer UPC/EAN AT+CH (ja/nein/über wen?) Exclusive Record Store Day version pressed on 7" picture disc! Top song on Billboard's 375Media Ace Of Base The Sign 7" 1 !K7 Pop SI 174427 730003726071 D 1994 Year End Chart. [ENG]Pink heavyweight 180 gram audiophile double vinyl LP. Not previously released on vinyl. 'Nam Myo Ho Ren Ge Kyo' was first released on CD only in 2007 by Ace Fu SPACE AGE 375MEDIA ACID MOTHERS TEMPLE NAM MYO HO REN GE KYO (RSD PINK VINYL) LP 2 PSYDEL 139791 5023693106519 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Records and now re-mastered by John Rivers at Woodbine Street Studio especially for RECORDINGS vinyl Out of print on vinyl since 1984, FIRST official vinyl reissue since 1984 -Chet Baker (1929 - 1988) was an American jazz trumpeter, actor and vocalist that needs little introduction. This reissue was remastered by Peter Brussee (Herman Brood) and is featuring the original album cover shot by Hans Harzheim (Pharoah Sanders, Coltrane & TIDAL WAVES 375MEDIA BAKER, CHET MR. B LP 1 JAZZ 139267 0752505992549 AT: 375 / CH: Irascible Sun Ra). Also included are the original liner notes from jazz writer Wim Van Eyle and MUSIC two bonus tracks that were not on the original vinyl release. This reissue comes as a deluxe 180g vinyl edition with obi strip_released exclusively for Record Store Day (UK & Europe) 2020. * Record Store Day 2020 Exclusive Release.* Features new artwork* LP pressed on pink vinyl & housed in a gatefold jacket Limited to 500 copies//Last Tango in Paris" is a 1972 film directed by Bernardo Bertolucci, saxplayer Gato Barbieri' did realize the soundtrack. -

Download System of a Down Steal This Album Rar

Download system of a down steal this album rar CLICK TO DOWNLOAD Listen free to System of a Down – Steal This Album! (Chic 'N' Stu, Innervision and more). 16 tracks (). is the third album by System of a Down. Produced by Rick Rubin and Daron Malakian, Steal This Album! was recorded in mid and released on November 26, by American Recordings. The album reached No. 15 in the Billboard Top System Of A Down-System Of A renuzap.podarokideal.ru 0; Size 38 MB; Fast download for credit 37 sekund - 0,01 € Slow download for free System Of A Down-Steal This renuzap.podarokideal.ru 41 MB; 0. Korpiklanni-Voice Of Wilderness rar. 59 MB; 0. Harlej - Čtyři z punku a renuzap.podarokideal.ru 58 MB; 0. Fast download for credit 38 sekund - 0,01 System of a Down - Steal this renuzap.podarokideal.ru 52 MB +1. System Of A Down - renuzap.podarokideal.ru 41 MB; 0. Iron Maiden - Seventh Son Of A Seventh Son ().rar. 42 MB +1. Wanastowi Vjecy - Lži,sex a renuzap.podarokideal.ru Steal This Album! System Of A Down. 16 tracks. Released in Tracklist. Listen free to System of a Down – Steal This Album. Incorrect tagging this album is called Steal This Album! Please correct your tags Discover more music, concerts, videos, and pictures with the largest catalogue online at renuzap.podarokideal.ru Studio Album (7) - Single (1) About six months after Mezmerize, System Of A Down released its direct follow-up, Hypnotize. Steal This Album! is the third studio album by System of a Down, released on November 26, , on American renuzap.podarokideal.rued by Rick Rubin and Daron Malakian, and reached #15 in the Billboard Top Both Serj Tankian and John Dolmayan have called Steal This Album! their favorite System of a Down Genre: Alternative metal. -

Ch. 17.4 the Cold War Divides the World I. Fighting for the Third World A

Ch. 17.4 The Cold War Divides the World I. Fighting for the Third World A. Cold War Strategies 1. Third World countries are economically poor and unstable 2. These countries are in need of a political and economic system in which to build upon; Soviet style Communism and U.S. style free market democracy A. Cold War Strategies 3. U.S. (CIA) and Soviet (KGB) intelligence agencies engaged in covert activities 4. Both countries would provide aid to countries for loyalty to their ideology B. Association of Nonaligned Nations 1. Nonaligned nations were 3rd World nations that wanted to maintain their independence from the U.S. and Soviet influence 2. India and Indonesia were able to maintain neutrality but most took sides II. Confrontations in Latin America A. Latin America 1. The economic gap between rich and poor began to push Latin America to seek aid from both the Soviets and U.S. 2. American businesses backed leaders that protected their interests but these leaders usually oppressed their citizens A. Latin America 3. Revolutionary movements begin in Latin America and the Soviets and U.S. begin to lend support to their respective sides B. Fidel Castro and the Cuban Revolution 1. Fidel Castro led a popular revolution vs. the U.S. supported dictator Fulgencio Batista in January 1959 2. He was praised at first for bringing social reforms and improving the economy 3. But then he suspended elections, jailed and executed opponents & controlled the press B. Fidel Castro and the Cuban Revolution 4. Castro nationalized the economy taking over U.S. -

Nicaragua: in Brief

Nicaragua: In Brief Maureen Taft-Morales Specialist in Latin American Affairs September 14, 2016 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R44560 Nicaragua: In Brief Summary This report discusses Nicaragua’s current politics, economic development and relations with the United States and provides context for Nicaragua’s controversial November 6, 2016, elections. After its civil war ended, Nicaragua began to establish a democratic government in the early 1990s. Its institutions remained weak, however, and they have become increasingly politicized since the late 1990s. Current President Daniel Ortega was a Sandinista (Frente Sandinista de Liberacion Nacional, FSLN) leader when the Sandinistas overthrew the dictatorship of Anastasio Somoza in 1979. Ortega was elected president in 1984. An electorate weary of war between the government and U.S.-backed contras denied him reelection in 1990. After three failed attempts, he won reelection in 2006, and again in 2011. He is expected to win a third term in November 2016 presidential elections. As in local, municipal, and national elections in recent years, the legitimacy of this election process is in question, especially after Ortega declared that no domestic or international observers would be allowed to monitor the elections and an opposition coalition was effectively barred from running in the 2016 elections. As a leader of the opposition in the legislature from 1990 to 2006, and as president since then, Ortega slowly consolidated Sandinista—and personal—control over Nicaraguan institutions. As Ortega has gained power, he reputedly has become one of the country’s wealthiest men. His family’s wealth and influence have grown as well, inviting comparisons to the Somoza family dictatorship. -

THE ARMENIAN Mirrorc SPECTATOR Since 1932

THE ARMENIAN MIRRORc SPECTATOR Since 1932 Volume LXXXXI, NO. 42, Issue 4684 MAY 8, 2021 $2.00 Rep. Kazarian Is Artsakh Toun Proposes Housing Solution Passionate about For 2020 Artsakh War Refugees Public Service By Harry Kezelian By Aram Arkun Mirror-Spectator Staff Mirror-Spectator Staff EAST PROVIDENCE, R.I. — BRUSSELS — One of the major results Katherine Kazarian was elected of the Artsakh War of 2020, along with the Majority Whip of the Rhode Island loss of territory in Artsakh, is the dislocation State House in January, but she’s no of tens of thousands of Armenians who have stranger to politics. The 30-year-old lost their homes. Their ability to remain in Rhode Island native was first elected Artsakh is in question and the time remain- to the legislative body 8 years ago ing to solve this problem is limited. Artsakh straight out of college at age 22. Toun is a project which offers a solution. Kazarian is a fighter for her home- The approach was developed by four peo- town of East Providence and her Ar- ple, architects and menian community in Rhode Island urban planners and around the world. And despite Movses Der Kev- the partisan rancor of the last several orkian and Sevag years, she still loves politics. Asryan, project “It’s awesome, it’s a lot of work, manager and co- but I do love the job. And we have ordinator Grego- a great new leadership team at the ry Guerguerian, in urban planning, architecture, renovation Khanumyan estimated that there are State House.” and businessman and construction site management in Arme- around 40,000 displaced people willing to Kazarian was unanimously elect- and philanthropist nia, Belgium and Lebanon. -

Russian Museums Visit More Than 80 Million Visitors, 1/3 of Who Are Visitors Under 18

Moscow 4 There are more than 3000 museums (and about 72 000 museum workers) in Russian Moscow region 92 Federation, not including school and company museums. Every year Russian museums visit more than 80 million visitors, 1/3 of who are visitors under 18 There are about 650 individual and institutional members in ICOM Russia. During two last St. Petersburg 117 years ICOM Russia membership was rapidly increasing more than 20% (or about 100 new members) a year Northwestern region 160 You will find the information aboutICOM Russia members in this book. All members (individual and institutional) are divided in two big groups – Museums which are institutional members of ICOM or are represented by individual members and Organizations. All the museums in this book are distributed by regional principle. Organizations are structured in profile groups Central region 192 Volga river region 224 Many thanks to all the museums who offered their help and assistance in the making of this collection South of Russia 258 Special thanks to Urals 270 Museum creation and consulting Culture heritage security in Russia with 3M(tm)Novec(tm)1230 Siberia and Far East 284 © ICOM Russia, 2012 Organizations 322 © K. Novokhatko, A. Gnedovsky, N. Kazantseva, O. Guzewska – compiling, translation, editing, 2012 [email protected] www.icom.org.ru © Leo Tolstoy museum-estate “Yasnaya Polyana”, design, 2012 Moscow MOSCOW A. N. SCRiAbiN MEMORiAl Capital of Russia. Major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation center of Russia and the continent MUSEUM Highlights: First reference to Moscow dates from 1147 when Moscow was already a pretty big town. -

Ukraine in World War II

Ukraine in World War II. — Kyiv, Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance, 2015. — 28 p., ill. Ukrainians in the World War II. Facts, figures, persons. A complex pattern of world confrontation in our land and Ukrainians on the all fronts of the global conflict. Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance Address: 16, Lypska str., Kyiv, 01021, Ukraine. Phone: +38 (044) 253-15-63 Fax: +38 (044) 254-05-85 Е-mail: [email protected] www.memory.gov.ua Printed by ПП «Друк щоденно» 251 Zelena str. Lviv Order N30-04-2015/2в 30.04.2015 © UINR, texts and design, 2015. UKRAINIAN INSTITUTE OF NATIONAL REMEMBRANCE www.memory.gov.ua UKRAINE IN WORLD WAR II Reference book The 70th anniversary of victory over Nazism in World War II Kyiv, 2015 Victims and heroes VICTIMS AND HEROES Ukrainians – the Heroes of Second World War During the Second World War, Ukraine lost more people than the combined losses Ivan Kozhedub Peter Dmytruk Nicholas Oresko of Great Britain, Canada, Poland, the USA and France. The total Ukrainian losses during the war is an estimated 8-10 million lives. The number of Ukrainian victims Soviet fighter pilot. The most Canadian military pilot. Master Sergeant U.S. Army. effective Allied ace. Had 64 air He was shot down and For a daring attack on the can be compared to the modern population of Austria. victories. Awarded the Hero joined the French enemy’s fortified position of the Soviet Union three Resistance. Saved civilians in Germany, he was awarded times. from German repression. the highest American The Ukrainians in the Transcarpathia were the first during the interwar period, who Awarded the Cross of War. -

System Sugar

FENDER PLAYERS CLUB SYSTEM OF A DOWN From the book: Best of Aggro-Metal Signature Licks by Troy Stetina #HL 695592. Book/CD $19.95 (US). AUDIO CLIP AUDIO CLIP - Slow Read more... SUGAR - Chorus (Guitar) Words and music by Daron Malakian, Serj Tankian, Shavo Odadjian, and John Dolmayan Copyright©1998 Sony/ATV Tunes LLC and Ddevil Music All Rights Administered by Sony/ATV Music Publishing, 8 Music Square West, Nashville, TN 327203 International Copyright Secured All Rights Reserved System of a Down is the collaboration of four musicians from L.A. that share one relatively unusual characteristic—they are all of Armenian heritage. Serj Tankian (vocals) and Daron Malakian (guitar) met in 1993 as their two bands shared the same rehearsal studio. Shortly thereafter, they united under the name Soil. After several lineup changes, including the addition of Shavo Odadjian (bass) and John Dolmayan (drums), System of a Down was finally born in 1995. Amid lyrical assaults ranging from the personal to aggressive political and social indictments, SOAD draws upon an unusually wide range of stylistic influences including rap, jazz, hardcore, goth, Middle-Eastern, and even Armenian music. Dynamics can change on a dime. Vocalist/lyricist Serj explains, “We don’t just concentrate on an aggressive sound, though we have that. Anger becomes more angry when you’re quiet at first.” Nowhere is that better exemplified than in “Sugar,” the third cut from their self- titled 1998 debut. First, a word about the tone: More than any other band in this book, the guitars in “Sugar” have a pronounced lower midrange peak in the 600-800 Hz range. -

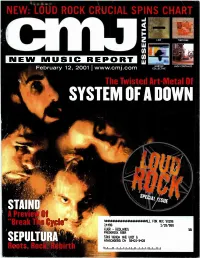

System of a Down Molds Metal Like Silly Putty, Bending and Shaping Its Parame- 12 Slayer's First Amendment Ters to Fit the Band's Twisted Vision

NEW: LOUD ROCK CRUCIAL SPINS CHART LOW TORTOISE 1111 NEW MUSIC REPORT Uà NORTEC JACK COSTANZO February 12, 20011 www.cmj.com COLLECTIVE The Twisted Art-Metal Of SYSTEM OF ADOWN 444****************444WALL FOR ADC 90138 24438 2/28/388 KUOR - REDLAHDS FREDERICK SUER S2V3HOD AUE unr G ATASCADER0 CA 88422-3428 IIii II i ti iii it iii titi, III IlitlIlli lilt ti It III ti ER THEIR SELF TITLED DEBUT AT RADIO NOW • FOR COLLEGE CONTACT PHIL KASO: [email protected] 212-274-7544 FOR METAL CONTACT JEN MEULA: [email protected] 212-274-7545 Management: Bryan Coleman for Union Entertainment Produced & Mixed by Bob Marlette Production & Engineering of bass and drum tracks by Bill Kennedy a OADRUNNEll ACME MCCOWN« ROADRUNNER www.downermusic.com www.roadrunnerrecords.com 0 2001 Roadrunner Records. Inc. " " " • Issue 701 • Vol 66 • No 7 FEATURES 8 Bucking The System member, the band is out to prove it still has Citing Jane's Addiction as a primary influ- the juice with its new release, Nation. ence, System Of A Down molds metal like Silly Putty, bending and shaping its parame- 12 Slayer's First Amendment ters to fit the band's twisted vision. Loud Follies Rock Editor Amy Sciarretto taps SOAD for Free speech is fodder for the courts once the scoop on its upcoming summer release. again. This time the principals involved are a headbanger institution and the parents of 10 It Takes A Nation daughter who was brutally murdered by three Some question whether Sepultura will ever of its supposed fans. be same without larger-than-life frontman 15 CM/A: Staincl Max Cavalera. -

Fidel Castro Calls Lor Solidarity Wnh Nicaragua

AUGUST 24, 1979 25 CENTS VOLUME 43/NUMBER 32 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE Carter stalls aid, seeks to strangle freedom fi9ht -- Mit;t.. ntll=rArl MANA~UA, August 3-Thousands of Nicaraguans from working-class and poor neighborhoods rally in support of revolution. on-the-scene reports Fidel castro -Workers & peasants calls lor rebuild country -PAGE 2 ·Sandinista leader appeals SOlidaritY for support -PAGE 16 wnh Nicaragua ~Statement by Full text-Pages 10-14 Fourth International-PAGE 6 In face of U.S. imP-erialist threat orkers and peasants By Pedro Camejo, Sergio Rodriguez and Fred Murphy MANAGUA, Nicaragua-The social ist revolution has begun in Nicaragua. Under the leadership of the Sandi nista National Liberation Front, the workers and peasants have over thrown the imperialist-backed Somoza dictatorship and destroyed its army and police force. Basing itself on the power of the armed and mobilized masses, the San dinista leadership has begun taking a series of radical measures-a deepgo ing land reform, nationalization of all the country's banks, seizure of all the property held by the Somoza family and its collaborators, the formation of popular militias and a revolutionary Pedro Camejo, a leader of the Socialist Workers Party, and Sergio Rodriguez, a leader of the Revolu tionary Workers Party of Mexico, went to Nicaragua to gather first hand information for the United Secretariat of the Fourth Interna tional, the world Trotskyist organi Victorious Nicaraguans drag statue of Somoza's father through streets of Managua zation, and for Trotskyists around the world. -

Failed Or Fragile States in International Power Politics

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2013 Failed or Fragile States in International Power Politics Nussrathullah W. Said CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/171 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Failed or Fragile States in International Power Politics Nussrathullah W. Said May 2013 Master’s Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of International Affairs at the City College of New York Advisor: Dr. Jean Krasno This thesis is dedicated to Karl Markl, an important member of my life who supported me throughout my college endeavor. Thank you Karl Markl 1 Contents Part I Chapter 1 – Introduction: Theoretical Framework………………………………1 The importance of the Issue………………………………………….6 Research Design………………………………………………………8 Methodology/Direction……………………………………………….9 Chapter 2 – Definition and Literature…………………………………………….10 Part II Chapter 3 – What is a Failed State? ......................................................................22 Chapter 4 – What Causes State Failure? ..............................................................31 Part III Chapter 5 – The Case of Somalia…………………………………………………..41 Chapter 6 – The Case of Yemen……………………………………………………50 Chapter 7 – The Case of Afghanistan……………………………………………...59 Who are the Taliban? …………………………………………….....66 Part IV Chapter 8 – Analysis………………………………………………………………79 Chapter 9 – Conclusion……………………………………………………………89 Policy Recommendations…………………………………………….93 Bibliography…………………………………………………….........95 2 Abstract The problem of failed states, countries that face chaos and anarchy within their border, is a growing challenge to the international community especially since September 11, 2001. -

Moscow Victory Parade to See Dozens of Russian World-Class Bestsellers

Moscow Victory Parade to see dozens of Russian world-class bestsellers Rosoboronexport, a member of Rostec, works ceaselessly to promote Russia's modern weapons in the world arms market. Some of them will end up in the parade to take place in Moscow on May 9 in commemoration of the Victory in the Great Patriotic War in 1941-1945. “While reminding us of the Great Victory, the parade serves as a demonstration of state-of- the-art equipment, developed by Russia's defense industry. Keeping up with the tradition, dozens of Russian weapons and military equipment will roll out to Red Square, including Uralvagonzavod’s armored vehicles, High Precision Systems’ SAMs, Tecmash’s MLRSs, Russian Helicopters’ aviation systems, etc. Among the most prominent newcomers is the upgraded A-50 flying radar, an airborne command post of the Air Force. Quite a few of Rostec’s products have proved their characteristics in real combat. Considerable interest in our equipment of foreign countries is evident in the ever-growing export,” notes Rostec's head Sergey Chemezov. Export derivatives of the Russian equipment expected in Red Square on May 9 are also listed in Rosoboronexport's catalog. These include Buk-M2E and Tor-M2E SAM systems, Pantsir-S1 gun and missile AD system, Iskander-E tactical missile system, Msta-S SP howitzer, Smerch multiple-launched rocket systems, numerous wheeled armored vehicles, namely Tigr-M, Typhoon-K and BTR-82A, as well as T-72-class tanks, BMPT tank support vehicle, IL-76MD-90A(E) military transport aircraft, MiG-29M multirole frontline fighter, Su-30SME multirole super-maneuverable fighter, Su-32 fighter-bomber and Su-35 multirole supermaneuverable fighter, Mi-28NE and Ka-52 gunships, and Mi-26T2 heavy transport helicopter.