The Australian Victory Contingent, 1946: Australia, Britain, And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Russian Museums Visit More Than 80 Million Visitors, 1/3 of Who Are Visitors Under 18

Moscow 4 There are more than 3000 museums (and about 72 000 museum workers) in Russian Moscow region 92 Federation, not including school and company museums. Every year Russian museums visit more than 80 million visitors, 1/3 of who are visitors under 18 There are about 650 individual and institutional members in ICOM Russia. During two last St. Petersburg 117 years ICOM Russia membership was rapidly increasing more than 20% (or about 100 new members) a year Northwestern region 160 You will find the information aboutICOM Russia members in this book. All members (individual and institutional) are divided in two big groups – Museums which are institutional members of ICOM or are represented by individual members and Organizations. All the museums in this book are distributed by regional principle. Organizations are structured in profile groups Central region 192 Volga river region 224 Many thanks to all the museums who offered their help and assistance in the making of this collection South of Russia 258 Special thanks to Urals 270 Museum creation and consulting Culture heritage security in Russia with 3M(tm)Novec(tm)1230 Siberia and Far East 284 © ICOM Russia, 2012 Organizations 322 © K. Novokhatko, A. Gnedovsky, N. Kazantseva, O. Guzewska – compiling, translation, editing, 2012 [email protected] www.icom.org.ru © Leo Tolstoy museum-estate “Yasnaya Polyana”, design, 2012 Moscow MOSCOW A. N. SCRiAbiN MEMORiAl Capital of Russia. Major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation center of Russia and the continent MUSEUM Highlights: First reference to Moscow dates from 1147 when Moscow was already a pretty big town. -

Fondation Pierre Du Bois | Ch

N°2 | February 2021 Structures of Genocide: Making Sense of the New War for Nagorno-Karabakh Joel Veldkamp * “Terrorists we’re fighting and we’re never gonna stop The prostitutes who prosecute have failed us from the start Can you see us?” - System of a Down, “Genocidal Humanoidz” On December 10, 2020, Turkey and Azerbaijan held a joint victory parade in Azerbaijan’s capital of Baku. Turkey’s president Tayyib Recep Erdogan and Azerbaijan’s president Ilham Aliyev stood together on a dais in front of twenty Turkish and Azerbaijani flags, as 3,000 members of the Azerbaijani Armed Forces marched by, displaying military hardware captured from their Armenian foes. Military bands played the anthems of the old Ottoman Empire, the Turkish dynasty that ruled much of the Middle East in the name of Islam until World War I. Azerbaijani jets roared over the capital, dropping smoke in the green, blue and red colors of the Azerbaijani flag. Certainly, there was much to celebrate. In forty-four days of brutal combat, Azerbaijani forces reversed the humiliating defeat they experienced at Armenia’s hands in 1994 and recaptured much of the disputed territory of Nagorno-Karabakh. Turkey worked with Azerbaijan hand-in-glove during the war, supplying it with weapons, providing intelligence and air support, and bringing in thousands of battle-hardened fighters from Syria to fight on the ground.1 The victory opened up the possibility that the hundreds of thousands of Azerbaijanis driven from Armenian-occupied territory in the first Karabakh war, many of whom had lived for decades in squalid camps in Baku and its environs, would be able to go home.2 It was an impressive vindication of the alliance of these two Turkish states, exemplifying their alliance’s motto, “two states, one nation.” But a darker spirit was on display during the parade. -

Ukraine in World War II

Ukraine in World War II. — Kyiv, Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance, 2015. — 28 p., ill. Ukrainians in the World War II. Facts, figures, persons. A complex pattern of world confrontation in our land and Ukrainians on the all fronts of the global conflict. Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance Address: 16, Lypska str., Kyiv, 01021, Ukraine. Phone: +38 (044) 253-15-63 Fax: +38 (044) 254-05-85 Е-mail: [email protected] www.memory.gov.ua Printed by ПП «Друк щоденно» 251 Zelena str. Lviv Order N30-04-2015/2в 30.04.2015 © UINR, texts and design, 2015. UKRAINIAN INSTITUTE OF NATIONAL REMEMBRANCE www.memory.gov.ua UKRAINE IN WORLD WAR II Reference book The 70th anniversary of victory over Nazism in World War II Kyiv, 2015 Victims and heroes VICTIMS AND HEROES Ukrainians – the Heroes of Second World War During the Second World War, Ukraine lost more people than the combined losses Ivan Kozhedub Peter Dmytruk Nicholas Oresko of Great Britain, Canada, Poland, the USA and France. The total Ukrainian losses during the war is an estimated 8-10 million lives. The number of Ukrainian victims Soviet fighter pilot. The most Canadian military pilot. Master Sergeant U.S. Army. effective Allied ace. Had 64 air He was shot down and For a daring attack on the can be compared to the modern population of Austria. victories. Awarded the Hero joined the French enemy’s fortified position of the Soviet Union three Resistance. Saved civilians in Germany, he was awarded times. from German repression. the highest American The Ukrainians in the Transcarpathia were the first during the interwar period, who Awarded the Cross of War. -

Moscow Victory Parade to See Dozens of Russian World-Class Bestsellers

Moscow Victory Parade to see dozens of Russian world-class bestsellers Rosoboronexport, a member of Rostec, works ceaselessly to promote Russia's modern weapons in the world arms market. Some of them will end up in the parade to take place in Moscow on May 9 in commemoration of the Victory in the Great Patriotic War in 1941-1945. “While reminding us of the Great Victory, the parade serves as a demonstration of state-of- the-art equipment, developed by Russia's defense industry. Keeping up with the tradition, dozens of Russian weapons and military equipment will roll out to Red Square, including Uralvagonzavod’s armored vehicles, High Precision Systems’ SAMs, Tecmash’s MLRSs, Russian Helicopters’ aviation systems, etc. Among the most prominent newcomers is the upgraded A-50 flying radar, an airborne command post of the Air Force. Quite a few of Rostec’s products have proved their characteristics in real combat. Considerable interest in our equipment of foreign countries is evident in the ever-growing export,” notes Rostec's head Sergey Chemezov. Export derivatives of the Russian equipment expected in Red Square on May 9 are also listed in Rosoboronexport's catalog. These include Buk-M2E and Tor-M2E SAM systems, Pantsir-S1 gun and missile AD system, Iskander-E tactical missile system, Msta-S SP howitzer, Smerch multiple-launched rocket systems, numerous wheeled armored vehicles, namely Tigr-M, Typhoon-K and BTR-82A, as well as T-72-class tanks, BMPT tank support vehicle, IL-76MD-90A(E) military transport aircraft, MiG-29M multirole frontline fighter, Su-30SME multirole super-maneuverable fighter, Su-32 fighter-bomber and Su-35 multirole supermaneuverable fighter, Mi-28NE and Ka-52 gunships, and Mi-26T2 heavy transport helicopter. -

Role of Turkey

Security Review GiorgiZurab B Batiashviliilanishvili Turkey-Greece Confrontation and Georgia: Threats and Challenges Turkey's Place and Role in the Second Karabakh War 2020 1 All rights reserved and belong to Georgian Foundation for Strategic and International Studies. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form, including electronic and mechanical, without the prior written permission of the publisher. The opinions and conclusions expressed are those of the author/s and do not necessarily reflect the views of Georgian Foundation for Strategic and International Studies. Copyright © 2020 Georgian Foundation for Strategic and International Studies 2 The second, 44-day war in Karabakh lasted from September 27 to November 10, 2020 ending with the signing of a ceasefire agreement by the presidents of Azerbaijan, Armenia and Russia. This document is plainly a capitulation of the Armenian side. This war has three clear winners - Azerbaijan, Russia and Turkey: - Azerbaijan, which after a 27-year pause, has regained control of most of the occupied territories, also enabling the return of refugees thereto. - Russia, which has deployed its peacekeeping forces in Nagorno-Karabakh for at least five years and gained control of the Lachin corridor connecting Armenia to Nagorno- Karabakh, will also control the pass connecting Nakhichevan to the rest of Azerbaijan.1 - Turkey, which became a game changer in the conflict by providing assistance to its brotherly Azerbaijani side. In fact, Ankara has for the first time and successfully participated in the ongoing military conflict in the post-Soviet space and strengthened its influence in the Caucasus. This issue, therefore, requires a more detailed discussion and analysis. -

Vladimir Putin and the Celebration of World War II in Russia*

! e Soviet and Post-Soviet Review 38 (2011) 172–200 brill.nl/spsr Performing Memory: Vladimir Putin and the Celebration of World War II in Russia* Elizabeth A. Wood Professor, History Faculty, M.I.T. Abstract By making World War II a personal event and also a sacred one, Vladimir Putin has created a myth and a ritual that elevates him personally, uniting Russia (at least theoretically) and showing him as the natural hero-leader, the warrior who is personally associated with defending the Motherland. Several settings illustrate this personal performance of memory: Putin’s meetings with veterans, his narration of his own family’s suff erings in the Leningrad blockade, his visits to churches associated with the war, his participation in parades and the creation of new uniforms, and his creation of a girls’ school that continues the military tradition. In each of these settings Putin demonstrates a connection to the war and to Russia’s greatness as dutiful son meeting with his elders, as legitimate son of Leningrad, and as father to a new generation of girls associated with the military. Each setting helps to reinforce a masculine image of Putin as a ruler who is both autocrat and a man of the people. Keywords Vladimir Putin ; World War II; memory ; patriotism; gender ; masculinity; Stalin ; Stalinism ; Dmitry Medvedev From his fi rst inauguration on May 7, 2000 and his fi rst Victory Day speech on May 9, 2000, over the course of the next eleven years, Vladimir Putin has repeatedly personifi ed himself as the defender, even the savior of the Motherland. -

Celebrating Diversity in the Guard and Reserve

DEOMI 2001 Calendar Cover Images The images on the cover of the 2001 DEOMI calendar attempts to capture the theme of the calendar, “A Celebration of Diversity and Multiculturalism in the Armed Forces Reserve and National Guard.” These images, from left to right and top to bottom are: Lt. Gen. Edward Baca, chief of the National Guard Bureau, 1992-96, is of Mexican-American heritage, from New Mexico. Appointed by President William Clinton in October 1994 as the Guard Bureau’s 24th chief, General Baca retired on July 31, 1998, after 42 years of military service. In his 46 months as chief of the National Guard Bureau, he was one of the most widely traveled chiefs in National Guard history, and influential in expanding the Guard’s horizons beyond this nation’s borders. Photo courtesy of National Guard Bureau A wounded WWI veteran of the 369th Infantry Regiment, 93d Infantry Division, watches the 1919 Victory Parade, New York City, with his family. Nicknamed “Harlem Hellfighters,” the much-decorated 369th was the redesignated National Guard 15th New York Infantry Regiment. Photo courtesy of New York State Division of Military and Naval Affairs: Military History The 200th Coast Artillery, a redesignated New Mexico National Guard unit, was photographed in preparations for defense of the Philippines in WWII. The predominantly Mexican-American unit, chosen partly for Spanish language skills, played a crucial role in covering the retreat of the Philippines’ defenders into Bataan. Photo courtesy of Bataan-Corregidor Memorial Foundation of New Mexico, IncSociety Cover of the Air National Guard magazine Citizen Airman. -

Karabakh Is Azerbaijan!

Karabakh is Azerbaijan! Karabakh is ancestral Azerbaijani land, one of its historical regions. Musa MARJANLI The name of this region translates into Russian as a “black garden”. Editor-in-Chief According to another version, it is a “large garden” or a “dense garden”. Up until the region was seized by the Russian Empire at the beginning of the 19th century, Karabakh was part of various Azerbaijani states. I will not bore you with arguments about who lived in Karabakh, who ruled it in certain historical periods – materials about that are available in most of the previous issues of IRS-Heritage. I only want to note that until the beginning of the 20th century, there was not a single Armenian ruler in Karabakh and indeed on the territory of present-day Armenia. This fact is graphic evidence that the Armenians always constituted an insignificant part of the population of these regions. On 14 May 1805, the ruler of the Karabakh Khanate, Ibrahim Khan, and the commander of the Russian troops, Prince P. Tsitsianov, signed the Treaty of Kurekchay, according to which the khanate was included in the Russian Empire. Subsequently, the Gulustan Peace Treaty of 18 October 1813 and the Turkmenchay Peace Treaty of 10 February 1828, signed as a result of two Russian-Iranian wars, formalized the final transfer of northern Azerbaijani khanates to the Russian Empire. Having taken possession of this land, Russia, striving to reinforce the Christian presence in the region, immediately began a systematic resettlement of Armenians here from Iran and the Ottoman Empire, placing them primarily on the lands of the former Azerbaijani khanates. -

September 2015 Rs

1 VOL. XXVII No. 9 September 2015 Rs. 20.00 Face Story: Commemoration of 70th Anniversary of Anti-fascist War Victory 2 Chinese Ambassador to India Le Yucheng gave a speech in Gujarat-Guangdong Economic and Trade Cooperation and Exchange Forum Chinese Ambassador to India Le Yucheng gave a speech Chinese Ambassador to India Le Yucheng visited in Jawaharlal Nehru University industrial park in Gujarat Chinese Ambassador to India Le Yucheng met with China Embassy and Huawei holds a table tennis members of India's senior diplomats delegation to China competition Commemoration of 70th anniversary of war victory 1. Chinese President’s Speech at Commemoration of 70th Anniversary of 6 Anti-fascist War Victory 2. Backgrounder: Military Parades to Mark Victory of World Anti-fascist War 12 3. Int’l Community Echoes Xi’s Speech at V-Day Commemoration 16 4. Overseas Experts, Scholars Applaud China’s Plan to Cut Troops 18 5. China Voice: Troop Cuts Signal Path of Peaceful Development 19 6. Commentary: Western Media Make Biased Reports on China’s Troop Cuts 20 7. The Message of China’s V-Day Parade 20 8. U.N. Chief, Experts Laud China’s Role in WWII 22 China-India Relations 1. Remarks by H.E. Ambassador Le Yucheng At Vivekananda 24 International Foundation: The Call of History 2. Ambassador Le Yucheng’s Letter to an Mumbai Little Girl 26 External Affairs 1. Li Keqiang’s speech at Summer Davos Opening Ceremony 28 2. China’s Economy Has Ups and Downs, But the Trend Remains Positive 34 3. RMB Exchange Rate Can Keep Basic Stability at Reasonable and 35 Balanced Level 4. -

China-Russia Relations: Tales of Two Parades, Two Drills, and Two Summits

Comparative Connections A Triannual E-Journal on East Asian Bilateral Relations China-Russia Relations: Tales of Two Parades, Two Drills, and Two Summits Yu Bin Wittenberg University In contrast to the inactivity in Sino-Russian relations in the first four months of the year, strategic interactions went into high gear in mid-year. It started on May 8 with the largest military parade in post-Soviet Russia for the 70th anniversary of the Great Patriotic War and ended on Sept. 3 when China staged its first-ever Victory Day parade for the 70th anniversary of its war of resistance against Japan’s invasion of China. In between, the Russian and Chinese navies held two exercises: Joint-Sea 2015 (I) in May in the Mediterranean and Joint Sea-2015 (II) in the Sea of Japan in August. In between the two exercises, the Russian city of Ufa hosted the annual summits of the SCO and BRICS, two multilateral forums sponsored and managed by Beijing and Moscow outside Western institutions. For all of these activities, Chinese media described Sino- Russian relations as “For Amity, Not Alliance.” Moscow’s Victory Day parade President Xi Jinping’s Moscow visit from May 8-10 was part of his three-country tour of Kazakhstan, Russia, and Belarus. The focal point of the Moscow stop was to join in the victory commemoration of the 70th anniversary of the Great Patriotic War, Russia’s name for World War II, and to meet Russian President Vladimir Putin. In the absence of Western leaders and military units (in 2010, US, UK, France, Ukraine, and Poland all sent military representatives to join the parade), who were boycotting the event to protest Russia’s takeover of Crimea, Xi was the most prominent among foreign dignitaries. -

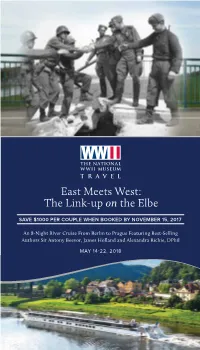

The Link-Up on the Elbe

East Meets West: The Link-up on the Elbe SAVE $1000 PER COUPLE WHEN BOOKED BY NOVEMBER 15, 2017 An 8-Night River Cruise From Berlin to Prague Featuring Best-Selling Authors Sir Antony Beevor, James Holland and Alexandra Richie, DPhil MAY 14-22, 2018 BRINGING HISTORY Dear Friend, TO LIFE The cornerstone of the Museum’s tremendously successful educational travel program is bringing enriching and unique experiences to our valued members, helping them to understand the many complexities of the war that changed One of the remarkable features of this program is the addition of our special the world. guest and Museum friend, Captain T. Moffatt Burriss. As a paratrooper with the One of the Museum’s exciting travel offerings is our new East Meets West: 82nd Airborne Division, Burriss saw combat at Sicily, Salerno, Anzio, Holland, the The Link-up on the Elbe. This program will delve into fascinating aspects of the Ardennes, and in Germany — where he raised a toast to Allied victory with Soviet war that seldom come to the attention of Americans, and it combines the comfort soldiers. His exhilarating personal stories will make this a memorable journey. and convenience of the newly launched MS Elbe Princess with visiting these As I’m sure you’ll agree, this is an important Museum trip for many reasons, historical sites. including the insights it will offer into the beginnings of the Cold War. And this is a rare opportunity to sail along a stunning river not often visited by Americans. The participation of the renowned authors and historians in the program reflects our commitment to providing an unparalleled experience. -

Public Celebrations in Soviet Ukraine Under Stalin (Kiev, 1943-1953) Author(S): Serhy Yekelchyk Source: Jahrbücher Für Geschichte Osteuropas, Neue Folge, Bd

The Leader, the Victory, and the Nation: Public Celebrations in Soviet Ukraine under Stalin (Kiev, 1943-1953) Author(s): Serhy Yekelchyk Source: Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas, Neue Folge, Bd. 54, H. 1, Themenschwerpunkt: Gespaltene Geschichtskulturen? Zweiter Weltkrieg und kollektive Erinnerungskulturen in der Ukraine (2006), pp. 3-19 Published by: Franz Steiner Verlag Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41051580 . Accessed: 25/05/2014 06:02 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Franz Steiner Verlag is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 208.67.143.49 on Sun, 25 May 2014 06:02:30 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions ABHANDLUNGEN Serhy Yekelchyk,Victoria/Canada The Leader, theVictory, and theNation: Public Celebrationsin SovietUkraine under Stalin (Kiev, 1943-1953)* Soviet troopsentered Kiev in the earlymorning hours of 6 November 1943. The residents were waiting forthe firstSoviet soldiers whom they welcomed, in the words of one early report,with tears in theireyes, but also with "cigarettes,home-made tobacco blend, wine, home-madeliqueur, and patties."1This descriptionreads more naturallythan a more formal contemporaryreport about the Kievans "expressingtheir profound gratitude to the Leader, Comrade Stalin,for his wise guidance of the Red Armyin the liberationof Kiev,"2 but I am not suggestingthat the latterinformation was false.