Peter Merchant Principal Lecturer, Canterbury Christ Church University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Europe College Yearbook 2015-2016

New Europe College ûWHIDQ2GREOHMD Program Yearbook 2015-2016 Program Yearbook 2015-2016 Program Yearbook ûWHIDQ2GREOHMD 1>4B55151>E 75?B791>18E91> F1C9<5=9819?<1BE NEW EUROPE COLLEGE NEW EUROPE CRISTIANA PAPAHAGI VANEZIA PÂRLEA 9E<9EB1 9E 1>4B51CCD1=1D5D561> ISSN 1584-0298 D85?4?B5E<95B9EB?CD£C CRIS New Europe College Ştefan Odobleja Program Yearbook 2015-2016 This volume was published within the Human Resources Program – PN II, implemented with the support of the Ministry of National Education – The Executive Agency for Higher Education and Research Funding (MEN – UEFISCDI), project code PN–II– RU–BSO-2015 EDITORIAL BOARD Dr. Dr. h.c. mult. Andrei PLEŞU, President of the New Europe Foundation, Professor of Philosophy of Religion, Bucharest; former Minister of Culture and former Minister of Foreign Affairs of Romania Dr. Valentina SANDU-DEDIU, Rector, Professor of Musicology, National University of Music, Bucharest Dr. Anca OROVEANU, Academic Coordinator, Professor of Art History, National University of Arts, Bucharest Dr. Irina VAINOVSKI-MIHAI, Publications Coordinator, Professor of Arab Studies, “Dimitrie Cantemir” Christian University, Bucharest Copyright – New Europe College 2017 ISSN 1584-0298 New Europe College Str. Plantelor 21 023971 Bucharest Romania www.nec.ro; e-mail: [email protected] Tel. (+4) 021.307.99.10, Fax (+4) 021. 327.07.74 New Europe College Ştefan Odobleja Program Yearbook 2015-2016 ANDREEA EŞANU GEORGIANA HUIAN VASILE MIHAI OLARU CRISTIANA PAPAHAGI VANEZIA PÂRLEA IULIU RAŢIU ANDREAS STAMATE-ŞTEFAN THEODOR E. ULIERIU-ROSTÁS -

The Sexual Politics of Meat by Carol J. Adams

THE SEXUAL POLITICS OF MEAT A FEMINISTVEGETARIAN CRITICAL THEORY Praise for The Sexual Politics of Meat and Carol J. Adams “A clearheaded scholar joins the ideas of two movements—vegetari- anism and feminism—and turns them into a single coherent and moral theory. Her argument is rational and persuasive. New ground—whole acres of it—is broken by Adams.” —Colman McCarthy, Washington Post Book World “Th e Sexual Politics of Meat examines the historical, gender, race, and class implications of meat culture, and makes the links between the prac tice of butchering/eating animals and the maintenance of male domi nance. Read this powerful new book and you may well become a vegetarian.” —Ms. “Adams’s work will almost surely become a ‘bible’ for feminist and pro gressive animal rights activists. Depiction of animal exploita- tion as one manifestation of a brutal patriarchal culture has been explored in two [of her] books, Th e Sexual Politics of Meat and Neither Man nor Beast: Feminism and the Defense of Animals. Adams argues that factory farming is part of a whole culture of oppression and insti- tutionalized violence. Th e treatment of animals as objects is parallel to and associated with patriarchal society’s objectifi cation of women, blacks, and other minorities in order to routinely exploit them. Adams excels in constructing unexpected juxtapositions by using the language of one kind of relationship to illuminate another. Employing poetic rather than rhetorical techniques, Adams makes powerful connec- tions that encourage readers to draw their own conclusions.” —Choice “A dynamic contribution toward creating a feminist/animal rights theory.” —Animals’ Agenda “A cohesive, passionate case linking meat-eating to the oppression of animals and women . -

Higher Laws" "Higher

tcny n<,rt IIInl J J A BENEFACTOR OF HIS RACE: THOREAU'S "HIGHER LAWS" AND THE HEROICS OF VEGETARIANISM ROBERT EPSTEIN grasped and lived by is the law which says: "Follow your own gen Berkeley, California ius"--be what you are, whether you are by your own nature hunter, or Was Thoreau a vegetarian or not? There wood chopper, or scholar. When you are several answers to this question. have become perfect you will be perfect; but only if you have If dietary practice is to be the sole learned to be, all along, what at criterion for judging, then Thoreau cannot be each manent you were. (pp 84-5) considered a vegetarian, since, by his own account, he ate fish and meat (though the Echoing Thoreau, the eminent psycholo latter rarely). gist, Carl G. Jung once wrote: Yet, despite this fact, Thoreau espoused I had to obey an inner law which a vegetarian ethic. So, his practice does was :irr\posed on me and left me no not suffice as a criterion for judging the freedanfreedom of choice. Of course I did extent of his vegetarianism. Consequently, not always obey it. How can anyone he has been criticized numerous times, e.g. live without inconsistency? (1965, by Wagenknecht, 1981, Garber, 1977, Jones, p. 356) 1954, for being inconsistent. How consistent was he in adhering to the vegetarian ideal? What we need to do in Thoreau scholarship- The question is not easy to answer. We must particularly regarding his dietary views--is ask: consistent from whose point of view? put aside our judgments of inconsistency The notion of consistency cannot always and (which frequently represent a defense against easily be objectively detennined,determined, because the areas of conflict in us) and attempt to un critic's own biases distort that which is derstand Thoreau franfrom within his own frame of ref~ence.[l] being viewed, in this case Thoreau's vegetar The question with which we ianism. -

Animal Rites and Justice

BEI'WEEN THE SPFX::IES 190 Although the service had supporters both Morning, a magazine for Presbyterian minis within and without the religious canmunity, a ters, a Presbyterian pastor accused the ser few ministers of the Christian faith, in vice of "humanism," stating that, "We are of particular two publicly and one through my the refonned. faith, the church refonned. al acquaintance, said they would not attend such ways reforming. I hardly believe that funer a service as ani.rna/ls do not have souls, and als like the one for Wind-of-Fire are steps therefore, it was inappropriate to hold a in this refonnation process." Another pas service which implied that anima/ls would tor, responding in the September, 1985, is participate in a resurrection, afterlife, or sued of the same magazine, countered this by in particular heaven. saying, "the pastor reports, and seemingly has problems with, the minister saying that Anna Kingsford, a nineteenth century God I S Love extends to all of creation and feminist/mystic and anima/l rights activist, offering prayers for animals that are victims pointed out that all forms of life are re of human injustice. I am disturbed by what garded as having souls within the Judea/ this seems to say both about the role of a Christian tradition. In Genesis, the word in pastor towards a grieving person and about Hebrew which applies to all living things is the relationship of humans to animals."[3] "Nephesh," meaning soul. As Kingsford points out, in '!he Perfect~, a series of her Q1e humorous response to the service lectures published in London in 1882, "had appeared in a column called "Insect Rights," the Bible been accurately translated, the by John C. -

Walks in Jefferies-Land 1912

Walks in Jefferies-Land 1912 Kate Tryon The RICHARD JEFFERIES SOCIETY (Registered Charity No. 1042838) was founded in 1950 to promote appreciation and study of the writings of Richard Jefferies (1848-1887). Website http://richardjefferiessociety.co.uk email [email protected] 01793 783040 The Kate Tryon manuscript In 2010, the Richard Jefferies Society published Kate Tryon’s memoir of her first visit to Jefferies’ Land in 1910. [Adventures in the Vale of the White Horse: Jefferies Land, Petton Books.] It was discovered that the author and artist had started work on another manuscript in 1912 entitled “Walks in Jefferies-Land”. However, this type-script was incomplete and designed to illustrate the places that Mrs Tryon had visited and portrayed in her oil-paintings using Jefferies’ own words. There are many pencilled-in additions to this type-script in Kate Tryon’s own hand- writing and selected words are underlined in red crayon. Page 13 is left blank, albeit that the writer does not come across as a superstitious person. The Jefferies’ quotes used are not word-perfect; neither is her spelling nor are her facts always correct. There is a handwritten note on the last page that reads: “This is supposed to be about half the book. – K.T.” The Richard Jefferies Society has edited the “Walks”, correcting obvious errors but not the use of American spelling in the main text. References for quotes have been added along with appropriate foot-notes. The Richard Jefferies Society is grateful to Kate Schneider (Kate Tryon’s grand- daughter) for allowing the manuscripts to be published and thanks Stan Hickerton and Jean Saunders for editing the booklet. -

THE ETERNAL HERMES from Greek God to Alchemical Magus

THE ETERNAL HERMES From Greek God to Alchemical Magus With thirty-nine plates Antoine Faivre Translated by Joscelyn Godwin PHANES PRESS 1995 © 1995 by Antoine Faivre. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, with the exception of short excerpts used in reviews, without permission in writing from the publisher. Book and cover design by David Fideler. Phanes Press publishes many fine books on the philosophical, spiritual, and cosmological traditions of the Western world. To receive a complete catalogue, please write: Phanes Press, PO Box 6114, Grand Rapids, MI 49516, USA. Library 01 Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Faivre, Antoine, 1934- The eternal Hermes: from Greek god to alchemical magus / Antoine Faivre; translated by Joscelyn Godwin p. cm. Articles originally in French, published separately. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-933999-53-4 (alk. paper)- ISBN 0-933999-52-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) I. Hennes (Greek deity) 2. Hermes, Trismegistus. 3. Hermetism History. 4. Alchemy-History. I. Title BL920.M5F35 1995 135'.4-<lc20 95-3854 elP Printed on permanent, acid-free paper. Printed in the United States of America. 9998979695 5432 1 Contents Preface ................................................................................. 11 Chapter One Hermes in the Western Imagination ................................. 13 Introduction: The Greek Hermes ....................................................... 13 The Thrice-Greatest ....................................................... -

Fornuft Og Følelser?

Morten Haugdahl Fornuft og følelser? Forståelser og forvaltning av hval og hvalfangst Avhandling for graden philosophiae doctor Trondheim, mai 2013 Norges teknisk-naturvitenskapelige universitet Det humanistiske fakultet Institutt for tverrfaglige kulturstudier NTNU Norges teknisk-naturvitenskapelige universitet Doktoravhandling for graden philosophiae doctor Det humanistiske fakultet Institutt for tverrfaglige kulturstudier © Morten Haugdahl ISBN 978-82-471-4348-3 (trykt utg.) ISBN 978-82-471-4349-0 (elektr. utg.) ISSN 1503-8181 Doktoravhandlinger ved NTNU, 2013:123 Trykket av NTNU-trykk In the whale, there is a man without his raincoat.1 Brian Eno 1 Brian Eno: Mother Whale Eyeless, Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy), Island Records 1974. 3 4 Forord At this moment, we are engaged in a showdown between life and death, good and evil, greed and compassion. It is a battle we must and will win!2 Dette arbeidet har vært en lang reise, som har utviklet seg i en særs annerledes retning enn jeg først hadde planlagt. Da jeg startet arbeidet i 2008, var ideen en ganske annen enn det jeg har endt opp med. Som en del av prosjektet ”Voices of Nature”, finansiert av MILJØ 2015 og Norges forskningsråd, begynte jeg å undersøke de mer radikale delene av miljøbevegelsen og deres forhold og bruk av vitenskap. 3 Arbeidstittelen for avhandlingen var ”Science and Monkeywrenching”. I en gjennomgang av publikasjoner fra miljøaktivistene i Earth First!, dukket hvalen og motstanden mot fangsten av den opp. Intensiteten i beskrivelsene av det jeg da først og fremst oppfattet som en symbolsk miljøkamp fascinerte meg, og jeg begynte å vurdere hvalfangsten som en case å ta med meg i det videre arbeidet. -

Shahed Ahmed Power

GANDHI DEEP ECOLOGY: -4 Experiencing thg Nonhuman Environment Shahed Ahmed Power Ph. D. Thesis Environmental Resources Unit, University of Salford 1990 r Dedicated to all my friends and to the memory of Sugata Dasgupta (1926 - 1984) iii Contents Page List of Maps iii Acknowledgements iv Abbreviations vi Abstract viii Introduction 1 The psychological background 4 Chapter I: GANDHI: The Early Years 12 Chapter II: GANDHI: South Africa 27 Chapter III: GANDHI: India 1915 - 1931 59 Chapter IV: GANDHI: India 1931 - 1948 93 Chapter V: THOREAU: 1817 - 1862 120 Chapter VI: Background to Deep Ecology 153 John Muir (1838 - 1914) 154 Richard Jefferies (1848 - 1887) 168 Mary Austin (1868 - 1934) 172 Aldo Leopold (1886 - 1948) 174 Richard St. Barbe Baker (1889 - 1982) 177 Indigenous People: 178 (i) Amerindian 179 (ii) North-East India 184 Chapter VII: ARNE NAESS 191 Chapter VIII: Summary & Synthesis 201 Bibliography 211 Appendix 233 List of Maps: Map of Indian Subcontinent - between pages 58 and 59 Map of North-East India - between pages 184 and 185 iv Acknowledgements: Though he is not mentioned in the main body of the text, I have-been greatly influenced by the writings and life of the American religious writer Thomas Merton (1915 - 1968). Born in Prades, France, Thomas Merton grew up in France, England and the United States. In 1941 he entered the Trappist monastery, the Abbey of Our Lady of Gethsemani, Kentucky, where he is now buried, though he died in Bangkok. The later Merton especially was a guide to much of my reading in the 1970s. For many years now I have treasured a copy of Merton's own selection from the writings of Gandhi on Non-Violence (Gandhi, 1965), as well as a collection of his essays on peace (Merton, 1976). -

Blavatsky on Anna Kingsford

Blavatsky on Anna Kingsford Blavatsky on Anna Kingsford v. 14.11, www.philaletheians.co.uk, 21 June 2018 Page 1 of 3 THEOSOPHY AND THEOSOPHISTS SERIES BLAVATSKY ON ANNA KINGSFORD Obituary First published in Lucifer, Vol. II, No. 7, March 1888, pp. 78-79. Republished in Blavatsky Collected Writings, (THE LATE MRS. ANNA KINGSFORD, M.D.) IX pp. 89-91. We have this month to record with the deepest regret the passing away from this physical world of one who, more than any other, has been instrumental in demon- strating to her fellow-creatures the great fact of the conscious existence — hence of the immortality — of the inner Ego. We speak of the death of Mrs. Anna Kingsford, M.D., which occurred on Tuesday, the 28th of February, after a somewhat painful and prolonged illness. Few women have worked harder than she has, or in more noble causes; none with more success in the cause of humanitarianism. Hers was a short but a most useful life. Her intellectual fight with the vivisectionists of Europe, at a time when the educated and scientific world was more strongly fixed in the grasp of materialism than at any other period in the history of civilisation, alone proclaims her as one of those who, regardless of con- ventional thought, have placed themselves at the very focus of the controversy, pre- pared to dare and brave all the consequences of their temerity. Pity and Justice to animals were among Mrs. Kingsford’s favourite texts when dealing with this part of her life’s work; and by reason of her general culture, her special training in the sci- ence of medicine, and her magnificent intellectual power, she was enabled to influ- ence and work in the way she desired upon a very large proportion of those people who listened to her words or who read her writings. -

Stallwood Collection Inventory Books.Numbers !1 of 33! Stallwood Collection Books 19/10/2013 Angell Geo

Stallwood Collection Books 19/10/2013 Aberconway Christabel A Dictionary of Cat Lovers London Michael Joseph 1949 0718100131 Abram David The Spell of the Sensuous New York Vintage Books 1997 0679776397 Acampora Ralph Corporal Compassion: Animal ethics and philosophy of body Pittsburgh, PA University of Pittsburgh Press 2006 822942852 Acciarini Maria Chiara Animali: I loro diritti i nostri 'doveri Roma Nuova Iniziativa Editoriale SpA LibraryThing Achor Amy Blount Animal Rights: A Beginner's Guide Yellow Springs, WriteWare, Inc. 1992 0963186507 OH Achor Amy Blount Animal Rights: A Beginner's Guide Yellow Springs, WriteWare, Inc. 1996 0963186507 OH Ackerman Diane The Zookeeper’s Wife London Old Street Publishing 2008 9781905847464 Adams Carol J. The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical New York Continuum 1990 0826404553 Theory Adams Carol J. The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical New York Continuum 1991 0826404553 Theory Adams Carol J., ed. Ecofeminism and the Sacred New York Continuum 1993 0883448408 Adams Carol J. Neither Man Nor Beast: Feminism and the Defense of Animals New York Continuum 1994 0826408036 Adams Carol J. Neither Man Nor Beast: Feminism and the Defense of Animals New York Continuum 1995 0826408036 Adams Carol J. and Josephine Animals & Women: Feminist Theoretical Explorations Durham, NC Duke University Press 1995 0822316676 Donovan, eds. Adams Carol J. and Josephine Beyond Animal Rights: A Feminist Caring Ethic for the New York Continuum 1996 0826412599 Donovan, eds. Treatment of Animals Adams Bluford E Pluribus Barnum: The great showman & the making of the Minneapolis, MN University of Minnesota Press 1997 0816626316 U.S. popular culture Adams Carol J. -

The Greek Vegetarian Encyclopedia Ebook, Epub

THE GREEK VEGETARIAN ENCYCLOPEDIA PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Diane Kochilas,Vassilis Stenos,Constantine Pittas | 208 pages | 15 Jul 1999 | St Martin's Press | 9780312200763 | English | New York, United States Vegetarianism - Wikipedia Auteur: Diane Kochilas. Uitgever: St Martin's Press. Samenvatting Greek cooking offers a dazzling array of greens, beans, and other vegetables-a vibrant, flavorful table that celebrates the seasons and regional specialties like none other. In this authoritative, exuberant cookbook, renowned culinary expert Diane Kochilas shares recipes for cold and warm mezes, salads, pasta and grains, stews and one-pot dishes, baked vegetable and bean specialties, stuffed vegetables, soup, savory pies and basic breads, and dishes that feature eggs and greek yogurt. Heart-Healthy classic dishes, regional favorites, and inspired innovations, The Greek Vegetarian pays tribute to one of the world's most venerable and healthful cuisines that play a major component in the popular Mediterranean Diet. Overige kenmerken Extra groot lettertype Nee Gewicht g Verpakking breedte mm Verpakking hoogte 19 mm Verpakking lengte mm. Toon meer Toon minder. Reviews Schrijf een review. Bindwijze: Paperback. Uiterlijk 30 oktober in huis Levertijd We doen er alles aan om dit artikel op tijd te bezorgen. Verkoop door bol. In winkelwagen Op verlanglijstje. Gratis verzending door bol. Andere verkopers 1. Bekijk en vergelijk alle verkopers. Soon their idea of nonviolence ahimsa spread to Hindu thought and practice. In Buddhism and Hinduism, vegetarianism is still an important religious practice. The religious reasons for vegetarianism vary from sparing animals from suffering to maintaining one's spiritual purity. In Christianity and Islam, vegetarianism has not been a mainstream practice although some, especially mystical, sects have practiced it. -

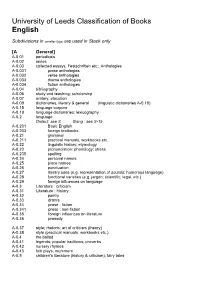

University of Leeds Classification of Books English

University of Leeds Classification of Books English Subdivisions in smaller type are used in Stack only [A General] A-0.01 periodicals A-0.02 series A-0.03 collected essays, Festschriften etc.; Anthologies A-0.031 prose anthologies A-0.032 verse anthologies A-0.033 drama anthologies A-0.034 fiction anthologies A-0.04 bibliography A-0.06 study and teaching; scholarship A-0.07 oratory; elocution A-0.09 dictionaries, literary & general (linguistic dictionaries A-0.19) A-0.15 language corpora A-0.19 language dictionaries; lexicography A-0.2 language Dialect: see S Slang : see S-15 A-0.201 Basic English A-0.203 foreign textbooks A-0.21 grammar A-0.211 practical manuals, workbooks etc. A-0.22 linguistic history; etymology A-0.23 pronunciation; phonology; stress A-0.235 spelling A-0.24 personal names A-0.25 place names A-0.26 punctuation A-0.27 literary uses (e.g. representation of sounds; humorous language) A-0.28 functional varieties (e.g. jargon; scientific, legal, etc.) A-0.29 foreign influences on language A-0.3 Literature : criticism A-0.31 Literature : history A-0.32 poetry A-0.33 drama A-0.34 prose : fiction A-0.341 prose : non-fiction A-0.35 foreign influences on literature A-0.36 prosody A-0.37 style; rhetoric; art of criticism (theory) A-0.38 style (practical manuals, workbooks etc.) A-0.4 the ballad A-0.41 legends; popular traditions; proverbs A-0.42 nursery rhymes A-0.43 folk plays; mummers A-0.5 children’s literature (history & criticism); fairy tales [B Old English] B-0.02 series B-0.03 anthologies of prose and verse Prose anthologies