Inner-City and Outer-City Neighbourhoods in Kolkata: Their Changing Dynamics Post Liberalization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

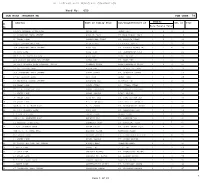

Jorasanko Assembly Constituency Total Polling Stations K.M.C

List of Polling Premises under 165 – Jorasanko Assembly Constituency Total Polling Stations K.M.C. Borough Police Sl. Name & Address of the Polling Premises Polling Attached Ward No No. Station Stations Shree Maheswari Vidyalaya, 4, Sovaram 1 8, 9, 11, 14, 16, 19 6 22 IV Posta Basak Street, Kolkata - 700 007 Nawal Kishore Daga Bikaner Walas 2 Dharmshala, 41, Kali Krishna Tagore Street, 1, 2, 3, 17 4 22 IV Posta Kolkata – 700 007 Maheshwari Balika Vidyalaya, 4, Sovaram 3 5, 6, 7, 12, 13, 18 6 22 IV Posta Basak Street, Kolkata - 700 007 Phulchand Mukimchand Jain Dharmasala, P- 4 4, 10, 22, 25 4 22 IV Posta 37 Kalakar Street, Kolkata - 700 007 Mukram Kanodia C. P. Model School, 9 Bartala 5 15, 20, 21 3 22 IV Posta Street, Kolkata - 700 007 Marwari Balika Vidyalaya, 29 Banstala Gulee, 23, 24, 36, 37, 40, 6 9 23 IV Posta Kolkata - 700 007 41, 43, 44, 45 Shree Didoo Maheswari Panchayat Vidyalaya 26, 31, 32, 33, 34, 7 8 23 IV Posta 259, Rabindra Sarani, Kolkata - 700 007 38, 39, 42 K.M.C.P. School, 15 Shibtala Street, Kolkata - 8 27, 28, 29, 30, 35 5 23 IV Posta 700 007 Nopany High, 2C, Nando Mullick Lane, Kolkata - 9 46, 47, 48, 49 4 25 IV Girish Park 700 006 Singhee Bagan High School for Girls, 7 10 50, 51, 52, 53 4 25 IV Girish Park Rajendra Mullick Street, Kolkata - 700 007 Rabindra Bharati University (Jorasanko 54, 55, 56, 63, 64, 11 Campus), 6/4 Dwarkanath Tagore Lane, 6 25 IV Girish Park 65 Kolkata - 700 007 Friend's United Club (Girish Park), 213B 12 58, 59 2 25 IV Girish Park Chittaranjan Avenue, Kolkata - 700 006 Peary Charan Girls High School, 146B Tarak 13 61, 62, 66, 67, 71 5 25 IV Girish Park Pramanick Road, Kolkata - 700 006 Goenka Hospital Building, 145 Muktaram Babu 14 57, 79, 80 3 25 IV Girish Park Street, Kolkata - 700 007 Sri Ram Narayan Singh Memorial High School, 15 68, 69 2 25 IV Girish Park 10 Dr. -

Lions Clubs International

Lions Clubs International Clubs Missing a Current Year Club Officer (Only President, Secretary or Treasurer) as of July 08, 2010 District 322 B2 Club Club Name Title (Missing) 34589 SHYAMNAGAR President 34589 SHYAMNAGAR Secretary 34589 SHYAMNAGAR Treasurer 42234 KANCHRAPARA President 42234 KANCHRAPARA Secretary 42234 KANCHRAPARA Treasurer 46256 CALCUTTA WOODLANDS President 46256 CALCUTTA WOODLANDS Secretary 46256 CALCUTTA WOODLANDS Treasurer 61410 CALCUTTA EAST WEST President 61410 CALCUTTA EAST WEST Secretary 61410 CALCUTTA EAST WEST Treasurer 63042 BASIRHAT President 63042 BASIRHAT Secretary 63042 BASIRHAT Treasurer 66648 AURANGABAD GREATER Secretary 66648 AURANGABAD GREATER Treasurer 66754 BERHAMPORE BHAGIRATHI President 66754 BERHAMPORE BHAGIRATHI Secretary 66754 BERHAMPORE BHAGIRATHI Treasurer 84993 CALCUTTA SHAKESPEARE SARANI President 84993 CALCUTTA SHAKESPEARE SARANI Secretary 84993 CALCUTTA SHAKESPEARE SARANI Treasurer 100797 KOLKATA INDIA EXCHANGE GREATER President 100797 KOLKATA INDIA EXCHANGE GREATER Secretary 100797 KOLKATA INDIA EXCHANGE GREATER Treasurer 101372 DUM DUM GREATER President 101372 DUM DUM GREATER Secretary 101372 DUM DUM GREATER Treasurer 102087 BARASAT CITY President 102087 BARASAT CITY Secretary 102087 BARASAT CITY Treasurer 102089 KOLKATA VIP PURWANCHAL President OFF0021 Run Date: 7/8/2010 11:44:11AM Page 1 of 2 Lions Clubs International Clubs Missing a Current Year Club Officer (Only President, Secretary or Treasurer) as of July 08, 2010 District 322 B2 Club Club Name Title (Missing) 102089 KOLKATA VIP -

Kolkata the Gazette

Registered No. WB/SC-247 No. WB(Part-III)/2021/SAR-9 The Kolkata Gazette Extraordinary Published by Authority SRAVANA 4] MONDAY, JUly 26, 2021 [SAKA 1943 PART III—Acts of the West Bengal Legislature. GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL LAW DEPARTMENT Legislative NOTIFICATION No. 573-L.—26th July, 2021.—The following Act of the West Bengal Legislature, having been assented to by the Governor, is hereby published for general information:— West Bengal Act IX of 2021 THE WEST BENGAL FINANCE ACT, 2021. [Passed by the West Bengal Legislature.] [Assent of the Governor was first published in the Kolkata Gazette, Extraordinary, of the 26th July, 2021.] An Act to amend the Indian Stamp Act, 1899, in its application to West Bengal and the West Bengal Goods and Services Tax Act, 2017. WHEREAS it is expedient to amend the Indian Stamp Act, 1899, in its application to 2 of 1899. West Bengal and the West Bengal Goods and Services Tax Act, 2017, for the purposes West Ben. Act and in the manner hereinafter appearing; XXVIII of 2017. It is hereby enacted in the Seventy-second Year of the Republic of India, by the Legislature of West Bengal, as follows:— Short title and 1. (1) This Act may be called the West Bengal Finance Act, 2021. commencement. (2) Save as otherwise provided, this section shall come into force with immediate effect, and the other provisions of this Act shall come into force on such date, with prospective or retrospective effect as required, as the State Government may, by 2 THE KOLKATA GAZETTE, EXTRAORDINARY, JUly 26, 2021 PART III] The West Bengal Finance Act, 2021. -

Cachar District

[TO BE PUBLISHED IN THE GAZETTE OF INDIA, EXTRAORDINARY, PART II SECTION 3, SUB SECTION (II)] GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF FINANCE (DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE) Notification No. 45/2010 - CUSTOMS (N.T.) 4th JUNE, 2010. 14 JYESTHA, 1932 (SAKA) S.O. 1322 (E). - In exercise of the powers conferred by clauses (b) and (c) of section 7 of the Customs Act, 1962 (52 of 1962), the Central Government hereby makes the following further amendment(s) in the notification of the Government of India in the Ministry of Finance (Department of Revenue), No. 63/94-Customs (NT) ,dated the 21st November, 1994, namely:- In the said notification, for the Table, the following Table shall be substituted, namely;- TABLE S. Land Land Customs Routes No. Frontiers Stations (1) (2) (3) (4) 1. Afghanistan (1) Amritsar Ferozepur-Amritsar Railway Line (via Railway Station Pakistan) (2) Delhi Railway Ferozepur-Delhi Railway Line. Station 2. Bangladesh CALCUTTA AND HOWRAH AREA (1) Chitpur (a) The Sealdah-Poradah Railway Line Railway Station passing through Gede Railway Station and Dhaniaghat and the Calcutta-Khulna Railway line River Station. passing through Bongaon (b) The Sealdah-Lalgola Railway line (c) River routes from Calcutta to Bangladesh via Beharikhal. (2) Jagannathghat The river routes from Calcutta to Steamer Station Bangladesh via Beharikhal. and Rajaghat (3) T.T. Shed The river routes from Calcutta to (Kidderpore) Bangladesh via Beharikhal. CACHAR DISTRICT (4) Karimganj (a) Kusiyara river Ferry Station (b) Longai river (c) Surma river (5) Karimganj (a) Kusiyara river Steamerghat (b) Surma river (c) Longai river (6) Mahisasan Railway line from Karimganj to Latu Railway Station Railway Station (7) Silchar R.M.S. -

Slum Diversity in Kolkata

SLUM DIVERSITY IN KOLKATA SLUM DIVERSITY IN KOLKATA W. COLLIN SCHENK UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA ABSTRACT: Kolkata's slums contain a wealth of diversity that is obscured by the poverty and disorganization surrounding the communities. This paper delineates the categories of slums according to their historical generative forces, details the ethnic composition of slums, and examines the historical patterns of slum policies. Case studies from other researchers are used to paint a picture of slum diversity. The data from the studies is also foundational in the analysis of how historical influences and ethnicity have shaped current conditions in the slums. 91 COLUMBIA UNDERGRADUATE JOURNAL OF SOUTH ASIAN STUDIES Introduction lum-dwellers account for one-third of Kolkata’s total population. This amounts to 1,490,811 people living without adequate basic amenities in over-crowded and S 1 unsanitary settlements. Considering the challenge of counting undocumented squatters and residents of sprawling bastis, this number may be a generous underestimate by the Indian census. The slums’ oftentimes indistinguishable physical boundaries further complicate researchers’ investigations of slums’ diverse physical, social, and economic compositions. In this paper, I will elucidate the qualities of Kolkata’s slums by utilizing past researchers’ admirable efforts to overcome these barriers in studying the slums. The general term slum can refer to both bastis and squatter settlements. Bastis are legally recognized settlements that the Kolkata Municipal Corporation supplies with services such as water, latrines, trash removal, and occasionally electricity. Basti huts typically are permanent structures that the government will not demolish, which allows basti communities to develop a sense of permanency and to focus on issues of poverty beyond shelter availability. -

Eastern Railway

2.1.1 पूव रेलवे EASTERN RAILWAY 20192019----2020 के िलए पƗरसंपिēयĪ कƙ खरीद , िनमाϕण और बदलाव Assets-Acquisition, Construction and Replacement for 2019-20 (Figures in thousand of Rupees)(आंकड़े हजार Đ . मĞ) पूंजी पूंजी िनिध मूआिन िविन संिन रारेसंको जोड़ िववरण Particulars Capital CF DRF. DF SF RRSK TOTAL 11 (a ) New Lines (Construction) 70,70,00 .. .. .. .. .. 70,70,00 14 G Gauge Conversion 2,00,00 .. .. .. .. .. 2,00,00 15 ह Doubling 9,80,95 .. .. .. .. .. 9,80,95 16 - G Traffic Facilities-Yard 21,22,84 .. 90,25 13,22,19 .. 29,97,50 65,32,78 G ^ G Remodelling & Others 17 Computerisation 3,51,00 .. 12,41,30 62,00 .. .. 16,54,30 21 Rolling Stock 30,24,90 .. .. 7,66 .. 37,56,01 67,88,57 22 * 4 - Leased Assets - Payment of 518,12,69 205,67,31 .. .. .. .. 723,80,00 Capital Component 29 E G - Road Safety Works-Level .. .. .. .. .. 38,60,00 38,60,00 Crossings. 30 E G -/ Road Safety Works-Road .. .. .. .. .. 113,06,79 113,06,79 Over/Under Bridges. 31 Track Renewals .. .. .. .. .. 587,20,77 587,20,77 32 G Bridge Works .. .. .. .. .. 69,69,90 69,69,90 33 G Signalling and .. .. .. .. .. 83,25,97 83,25,97 Telecommunication 36 ^ G - G Other Electrical Works excl 1,34,17 .. 4,38,47 2,62,72 .. 5,08,29 13,43,65 K TRD 37 G G Traction Distribution Works 16,00,00 .. .. .. .. 110,59,55 126,59,55 41 U Machinery & Plant 5,16,94 . -

Mukhopadhyay, Aparajita (2013) Wheels of Change?: Impact of Railways on Colonial North Indian Society, 1855-1920. Phd Thesis. SO

Mukhopadhyay, Aparajita (2013) Wheels of change?: impact of railways on colonial north Indian society, 1855‐1920. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/17363 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Wheels of Change? Impact of railways on colonial north Indian society, 1855-1920. Aparajita Mukhopadhyay Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD in History 2013 Department of History School of Oriental and African Studies University of London 1 | P a g e Declaration for Ph.D. Thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work that I present for examination. -

Kolkata Police Notification to House Owners

Kolkata Police notification to House Owners The Commissioner of Police, Kolkata and Executive Magistrate has ordered u/s 144 of CrPC, 1973, that no landlord/owner/person whose house property falls under the jurisdiction of the area of Police Station specified in the Schedule–I appended below shall let/sublet/rent out any accommodation to any persons unless and untill he/she has furnished the particulars of the said tenants as per proforma in Schedule–II appended below to the Officer–in-Charge of the Police Station concerned. All persons who intend to take accommodation on rent shall inform in writing in this regard to the Officer-in–Charge of the Police Station concerned in whose jurisdiction the premises fall. The persons dealing in property business shall also inform in writing to the Officer-in-Charge of the Police Station concerned in whose jurisdiction the premises fall about the particulars of the tenants. This order has come into force from 9.7.2012 and shall be effective for a period of 60 days i.e. upto 6.9.2012 unless withdrawn earlier. Schedule-I Divisionwise PS List Sl. Sl. No. North Division E.S.D Sl. No. Central Division No. 1. Shyampukur PS 1. Manicktala PS 1. Burrabazar PS 2. Jorabagan PS 2. Ultadanga PS 2. Posta PS 3. Burtala PS 3. Entally PS 3. Jorasanko PS 4. Amherst St. PS 4. Phoolbagan PS 4. Hare Street PS 5. Cossipore PS 5. Narkeldanga PS 5. Bowbazar PS 6. Chitpur PS 6. Beniapukur PS 6. Muchipara PS 7. Sinthee PS 7. -

Urban Ethnic Space: a Discourse on Chinese Community in Kolkata, West Bengal

Indian Journal of Spatial Science Spring Issue, 10 (1) 2019 pp. 25 - 31 Indian Journal of Spatial Science Peer Reviewed and UGC Approved (Sl No. 7617) EISSN: 2249 - 4316 homepage: www.indiansss.org ISSN: 2249 - 3921 Urban Ethnic Space: A Discourse on Chinese Community in Kolkata, West Bengal Sudipto Kumar Goswami Research Scholar, Department of Geography, Visva-Bharati, India Dr.Uma Sankar Malik Professor of Geography, Department of Geography, Visva-Bharati, India Article Info Abstract _____________ ___________________________________________________________ Article History The modern urban societies are pluralistic in nature, as cities are the destination of immigration of the ethnic diaspora from national and international sources. All ethnic groups set a cultural distinction Received on: from another group which can make them unlike from the other groups. Every culture is filled with 20 August 2018 traditions, values, and norms that can be traced back over generations. The main focus of this study is to Accepted inRevised Form on : identify the Chinese community with their history, social status factor, changing pattern of Social group 31 December, 2018 interaction, value orientation, language and communications, family life process, beliefs and practices, AvailableOnline on and from : religion, art and expressive forms, diet or food, recreation and clothing with the spatial and ecological 21 March, 2019 frame in mind. So, there is nothing innate about ethnicity, ethnic differences are wholly learned through __________________ the process of socialization where people assimilate with the lifestyles, norms, beliefs of their Key Words communities. The Chinese community of Kolkata which group possesses a clearly defined spatial segmentation in the city. They have established unique modes of identity in landscape, culture, Ethnicity economic and inter-societal relations. -

Ward No: 050 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79

BPL LIST-KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION Ward No: 050 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79 Member Sl Address Name of Family Head Son/Daughter/Wife of BPL ID Year No Male Female Total 1 11,N/9 NATABAR DUTTA ROAD ADURI DAS SANAT DAS 2 2 4 2 2 32 SHANKHARI TALA STREET AJAY KR PAUL LT HARA PRASAD PAUL 3 4 7 6 3 25 CREEK LANE ALEKZANDER GOMES LT. FRILISH GOMES 3 2 5 10 4 100/F SERPENTINE LANE ALOK KUNDU LT PARESH KUNDU 2 2 4 12 5 30A SHANKHARI TALA STREET ANIL DAS LT. KISHORI MOHAN DAS 3 1 4 19 6 36 SURI LANE ANIL OJHA LT. DEBNARAYAN OJHA 2 3 5 21 7 97/2 S. N. BANERJEE ROAD ANIL ROY INER DEO ROY 3 0 3 22 8 4/A SHASHI BHUSHAN DEY STREET ANIMA DEY LT. AMAL DEY 1 2 3 24 9 3A JADU SRIMANI LANE KOLKATA 700014 ANIMESH GHOSH LATE HEMANTA K GHOSH 2 2 4 25 10 22/1E DICKSON LANE ANITA KAR LT. SUBODH CH. KAR 2 1 3 26 11 30A SHANKHARI TALA STREET ANNTA GAYEN LT. GURUPADA GAYEN 1 1 2 28 12 16/1C DICKSON LANE APU JANA MANTU JANA 3 0 3 29 13 18 MAHENDRA SARKAR STREET ASHALATA DAS ASHUTOSH DAS 2 2 4 34 14 19 CREEK LANE ASHOK GOMES LT. JOSHEF GOMES 2 3 5 35 15 77 S. N. BANERJEE ROAD ASHOK JOYSHAWAL LT. KAMALA JOYSHAWAL 2 1 3 37 16 25 CREEK LANE ASHOK NASKAR BINOD NASKAR 1 2 3 38 17 30 CREEK LANE ASIT KR. -

The Great Calcutta Killings Noakhali Genocide

1946 : THE GREAT CALCUTTA KILLINGS AND NOAKHALI GENOCIDE 1946 : THE GREAT CALCUTTA KILLINGS AND NOAKHALI GENOCIDE A HISTORICAL STUDY DINESH CHANDRA SINHA : ASHOK DASGUPTA No part of this publication can be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the author and the publisher. Published by Sri Himansu Maity 3B, Dinabandhu Lane Kolkata-700006 Edition First, 2011 Price ` 500.00 (Rupees Five Hundred Only) US $25 (US Dollars Twenty Five Only) © Reserved Printed at Mahamaya Press & Binding, Kolkata Available at Tuhina Prakashani 12/C, Bankim Chatterjee Street Kolkata-700073 Dedication In memory of those insatiate souls who had fallen victims to the swords and bullets of the protagonist of partition and Pakistan; and also those who had to undergo unparalleled brutality and humility and then forcibly uprooted from ancestral hearth and home. PREFACE What prompted us in writing this Book. As the saying goes, truth is the first casualty of war; so is true history, the first casualty of India’s struggle for independence. We, the Hindus of Bengal happen to be one of the worst victims of Islamic intolerance in the world. Bengal, which had been under Islamic attack for centuries, beginning with the invasion of the Turkish marauder Bakhtiyar Khilji eight hundred years back. We had a respite from Islamic rule for about two hundred years after the English East India Company defeated the Muslim ruler of Bengal. Siraj-ud-daulah in 1757. But gradually, Bengal had been turned into a Muslim majority province. -

Kolkata Municipal Corporation Ward No. 52

KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION WARD NO. 52 DOCUMENTED & PREPARED BY MAULANA AZAD COLLEGE KOLKATA-700013 MARCH, 2020 CONTRIBUTORS Dr. Subhasis Panda (Botany) Dr. Dipak Kumar Som (Zoology) Dr. Santanu Ghosh (Economics) Dr. Avishek Ghosh (Microbiology) Dr. Mahua Patra (Sociology) Dr. Partha Pal (Statistics) BOTANY, ZOOLOGY, MICROBIOLOGY, ECONOMICS, SOCIOLOGY & STATISTICS (Total = 41) 1. Introduction Ward-Number: 52 [ Borough: VI District: KOLKATA State: WEST BENGAL Location: It is an administrative division of Kolkata Municipal Corporation in Borough No. 5, covering parts of Taltala (Collin Street-Marquis Street) and Janbazar neighbourhoods in central Kolkata, in the Indian state of West Bengal. Habitat and topography Ward No. 52 is bordered on the north by Lenin Sarani, on the east by Rafi Ahmed Kidwai Street, on the south by Marquis Street and on the west by Rani Rashmoni Street and Mirza Ghalib Street. The ward is served by Taltala and New Market police stations of Kolkata Police. Taltala Women police station covers all police districts under the jurisdiction of the Central division of Kolkata Police, i.e. Bowbazar, Burrabazar, Girish Park, Hare Street, Jorasanko, Muchipara, New Market, Taltala and Posta. Agriculture: Nil Forests: Nil Climate: Kolkata has a Tropical wet-and-dry climate. The annual mean temperature is 24.8 °C (80 °F); monthly mean temperatures range from 15 °C to 30 °C (59 °F to 86 °F). Summers are hot and humid with temperatures in the low 30's and during dry spells the maximum temperatures often exceed 40 °C (104 °F) during May and June.[1] Winter tends to last for only about two and a half months, with seasonal lows dipping to 9 °C 11 °C (48.2 °F 51.8 °F) between December and January.