Neighbourhood, City, Diaspora

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kolkata Police Notification to House Owners

Kolkata Police notification to House Owners The Commissioner of Police, Kolkata and Executive Magistrate has ordered u/s 144 of CrPC, 1973, that no landlord/owner/person whose house property falls under the jurisdiction of the area of Police Station specified in the Schedule–I appended below shall let/sublet/rent out any accommodation to any persons unless and untill he/she has furnished the particulars of the said tenants as per proforma in Schedule–II appended below to the Officer–in-Charge of the Police Station concerned. All persons who intend to take accommodation on rent shall inform in writing in this regard to the Officer-in–Charge of the Police Station concerned in whose jurisdiction the premises fall. The persons dealing in property business shall also inform in writing to the Officer-in-Charge of the Police Station concerned in whose jurisdiction the premises fall about the particulars of the tenants. This order has come into force from 9.7.2012 and shall be effective for a period of 60 days i.e. upto 6.9.2012 unless withdrawn earlier. Schedule-I Divisionwise PS List Sl. Sl. No. North Division E.S.D Sl. No. Central Division No. 1. Shyampukur PS 1. Manicktala PS 1. Burrabazar PS 2. Jorabagan PS 2. Ultadanga PS 2. Posta PS 3. Burtala PS 3. Entally PS 3. Jorasanko PS 4. Amherst St. PS 4. Phoolbagan PS 4. Hare Street PS 5. Cossipore PS 5. Narkeldanga PS 5. Bowbazar PS 6. Chitpur PS 6. Beniapukur PS 6. Muchipara PS 7. Sinthee PS 7. -

Urban Ethnic Space: a Discourse on Chinese Community in Kolkata, West Bengal

Indian Journal of Spatial Science Spring Issue, 10 (1) 2019 pp. 25 - 31 Indian Journal of Spatial Science Peer Reviewed and UGC Approved (Sl No. 7617) EISSN: 2249 - 4316 homepage: www.indiansss.org ISSN: 2249 - 3921 Urban Ethnic Space: A Discourse on Chinese Community in Kolkata, West Bengal Sudipto Kumar Goswami Research Scholar, Department of Geography, Visva-Bharati, India Dr.Uma Sankar Malik Professor of Geography, Department of Geography, Visva-Bharati, India Article Info Abstract _____________ ___________________________________________________________ Article History The modern urban societies are pluralistic in nature, as cities are the destination of immigration of the ethnic diaspora from national and international sources. All ethnic groups set a cultural distinction Received on: from another group which can make them unlike from the other groups. Every culture is filled with 20 August 2018 traditions, values, and norms that can be traced back over generations. The main focus of this study is to Accepted inRevised Form on : identify the Chinese community with their history, social status factor, changing pattern of Social group 31 December, 2018 interaction, value orientation, language and communications, family life process, beliefs and practices, AvailableOnline on and from : religion, art and expressive forms, diet or food, recreation and clothing with the spatial and ecological 21 March, 2019 frame in mind. So, there is nothing innate about ethnicity, ethnic differences are wholly learned through __________________ the process of socialization where people assimilate with the lifestyles, norms, beliefs of their Key Words communities. The Chinese community of Kolkata which group possesses a clearly defined spatial segmentation in the city. They have established unique modes of identity in landscape, culture, Ethnicity economic and inter-societal relations. -

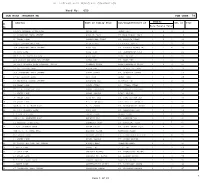

Ward No: 050 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79

BPL LIST-KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION Ward No: 050 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79 Member Sl Address Name of Family Head Son/Daughter/Wife of BPL ID Year No Male Female Total 1 11,N/9 NATABAR DUTTA ROAD ADURI DAS SANAT DAS 2 2 4 2 2 32 SHANKHARI TALA STREET AJAY KR PAUL LT HARA PRASAD PAUL 3 4 7 6 3 25 CREEK LANE ALEKZANDER GOMES LT. FRILISH GOMES 3 2 5 10 4 100/F SERPENTINE LANE ALOK KUNDU LT PARESH KUNDU 2 2 4 12 5 30A SHANKHARI TALA STREET ANIL DAS LT. KISHORI MOHAN DAS 3 1 4 19 6 36 SURI LANE ANIL OJHA LT. DEBNARAYAN OJHA 2 3 5 21 7 97/2 S. N. BANERJEE ROAD ANIL ROY INER DEO ROY 3 0 3 22 8 4/A SHASHI BHUSHAN DEY STREET ANIMA DEY LT. AMAL DEY 1 2 3 24 9 3A JADU SRIMANI LANE KOLKATA 700014 ANIMESH GHOSH LATE HEMANTA K GHOSH 2 2 4 25 10 22/1E DICKSON LANE ANITA KAR LT. SUBODH CH. KAR 2 1 3 26 11 30A SHANKHARI TALA STREET ANNTA GAYEN LT. GURUPADA GAYEN 1 1 2 28 12 16/1C DICKSON LANE APU JANA MANTU JANA 3 0 3 29 13 18 MAHENDRA SARKAR STREET ASHALATA DAS ASHUTOSH DAS 2 2 4 34 14 19 CREEK LANE ASHOK GOMES LT. JOSHEF GOMES 2 3 5 35 15 77 S. N. BANERJEE ROAD ASHOK JOYSHAWAL LT. KAMALA JOYSHAWAL 2 1 3 37 16 25 CREEK LANE ASHOK NASKAR BINOD NASKAR 1 2 3 38 17 30 CREEK LANE ASIT KR. -

Inner-City and Outer-City Neighbourhoods in Kolkata: Their Changing Dynamics Post Liberalization

Article Environment and Urbanization ASIA Inner-city and Outer-city 6(2) 139–153 © 2015 National Institute Neighbourhoods in Kolkata: of Urban Affairs (NIUA) SAGE Publications Their Changing Dynamics sagepub.in/home.nav DOI: 10.1177/0975425315589157 Post Liberalization http://eua.sagepub.com Annapurna Shaw1 Abstract The central areas of the largest metropolitan cities in India are slowing down. Outer suburbs continue to grow but the inner city consisting of the oldest wards is stagnating and even losing population. This trend needs to be studied carefully as its implications are deep and far-reaching. The objective of this article is to focus on what is happening to the internal structure of the city post liberalization by highlighting the changing dynamics of inner-city and outer-city neighbourhoods in Kolkata. The second section provides a brief background to the metropolitan region of Kolkata and the city’s role within this region. Based on ward-level census data for the last 20 years, broad demographic changes under- gone by the city of Kolkata are examined in the third section. The drivers of growth and decline and their implications for livability are discussed in the fourth section. In the fifth section, field observations based on a few representative wards are presented. The sixth section concludes the article with policy recommendations. 加尔各答内城和外城社区:后自由主义化背景下的动态变化 印度最大都市区中心地区的发展正在放缓。远郊持续增长,但拥有最老城区的内城停滞不 前,甚至出现人口外流。这种趋势需要仔细研究,因为它的影响是深刻而长远的。本文的目 的是,通过强调加尔各答内城和外城社区的动态变化,关注正在发生的后自由化背景下的城 市内部结构。第二部分提供了概括性的背景,介绍了加尔各答的大都市区,以及城市在这个 区域内的角色。在第三部分中,基于过去二十年城区层面的人口普查数据,研究考察了加尔 各答城市经历的广泛的人口变化。第四部分探讨了人口增长和衰退的推动力,以及它们对于 城市活力的影响。第五部分展示了基于几个有代表性城区的实地观察。第六部分提出了结论 与政策建议。 Keywords Inner city, outer city, growth, decline, neighbourhoods 1 Professor, Public Policy and Management Group, Indian Institute of Management Calcutta, Kolkata, India. -

Kolkata Municipal Corporation Ward No. 52

KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION WARD NO. 52 DOCUMENTED & PREPARED BY MAULANA AZAD COLLEGE KOLKATA-700013 MARCH, 2020 CONTRIBUTORS Dr. Subhasis Panda (Botany) Dr. Dipak Kumar Som (Zoology) Dr. Santanu Ghosh (Economics) Dr. Avishek Ghosh (Microbiology) Dr. Mahua Patra (Sociology) Dr. Partha Pal (Statistics) BOTANY, ZOOLOGY, MICROBIOLOGY, ECONOMICS, SOCIOLOGY & STATISTICS (Total = 41) 1. Introduction Ward-Number: 52 [ Borough: VI District: KOLKATA State: WEST BENGAL Location: It is an administrative division of Kolkata Municipal Corporation in Borough No. 5, covering parts of Taltala (Collin Street-Marquis Street) and Janbazar neighbourhoods in central Kolkata, in the Indian state of West Bengal. Habitat and topography Ward No. 52 is bordered on the north by Lenin Sarani, on the east by Rafi Ahmed Kidwai Street, on the south by Marquis Street and on the west by Rani Rashmoni Street and Mirza Ghalib Street. The ward is served by Taltala and New Market police stations of Kolkata Police. Taltala Women police station covers all police districts under the jurisdiction of the Central division of Kolkata Police, i.e. Bowbazar, Burrabazar, Girish Park, Hare Street, Jorasanko, Muchipara, New Market, Taltala and Posta. Agriculture: Nil Forests: Nil Climate: Kolkata has a Tropical wet-and-dry climate. The annual mean temperature is 24.8 °C (80 °F); monthly mean temperatures range from 15 °C to 30 °C (59 °F to 86 °F). Summers are hot and humid with temperatures in the low 30's and during dry spells the maximum temperatures often exceed 40 °C (104 °F) during May and June.[1] Winter tends to last for only about two and a half months, with seasonal lows dipping to 9 °C 11 °C (48.2 °F 51.8 °F) between December and January. -

BUS ROUTE-18-19 Updated Time.Xls LIST of DROP ROUTES & STOPPAGES TIMINGS LIST of DROP ROUTES & STOPPAGES TIMINGS

LIST OF DROP ROUTES & STOPPAGES TIMINGS LIST OF DROP ROUTES & STOPPAGES TIMINGS FOR THE SESSION 2018-19 FOR THE SESSION 2018-19 ESTIMATED TIMING MAY CHANGE SUBJECT ESTIMATED TIMING MAY CHANGE SUBJECT TO TO CONDITION OF THE ROAD CONDITION OF THE ROAD ROUTE NO - 1 ROUTE NO - 2 SL NO. LIST OF DROP STOPPAGES TIMINGS SL NO. LIST OF DROP STOPPAGES TIMINGS 1 DUMDUM CENTRAL JAIL 13.00 1 IDEAL RESIDENCY 13.05 2 CLIVE HOUSE, MALL ROAD 13.03 2 KANKURGACHI MORE 13.07 3 KAJI PARA 13.05 3 MANICKTALA RAIL BRIDGE 13.08 4 MOTI JEEL 13.07 4 BAGMARI BAZAR 13.10 5 PRIVATE ROAD 13.09 5 MANICKTALA P.S. 13.12 6 CHATAKAL DUMDUM ROAD 13.11 6 MANICKTALA DINENDRA STREET XING 13.14 7 HANUMAN MANDIR 13.13 7 MANICKTALA BLOOD BANK 13.15 8 DUMDUM PHARI 01:15 8 GIRISH PARK METRO STATION 13.20 9 DUMDUM STATION 01:17 9 SOVABAZAR METRO STATION 13.23 10 7 TANK, DUMDUM RD 01:20 10 B.K.PAUL AVENUE 13.25 11 AHIRITALA SITALA MANDIR 13.27 12 JORABAGAN PARK 13.28 13 MALAPARA 13.30 14 GANESH TALKIES 13.32 15 RAM MANDIR 13.34 16 MAHAJATI SADAN 13.37 17 CENTRAL AVENUE RABINDRA BHARATI 13.38 18 M.G.ROAD - C.R.AVENUE XING 13.40 19 MOHD.ALI PARK 13.42 20 MEDICAL COLLEGE 13.44 21 BOWBAZAR XING 13.46 22 INDIAN AIRLINES 13.48 23 HIND CINEMA XING 13.50 24 LEE MEMORIAL SCHOOL - LENIN SR. 13.51 ROUTE NO - 3 ROUTE NO - 04 SL NO. -

Market Photos 1 - 15 a B - a C MARKET

GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL AGRICULTURAL MARKET DIRECTORY MARKET SURVEY REPORT YEAR : 2011-2012 DISTRICT : KOLKATA THE DIRECTORATE OF AGRICULTURAL MARKETING P-16, INDIA EXCHANGE PLACE EXTN. CIT BUILDING, 4 T H F L O O R KOLKATA-700073 THE DIRECTORATE OF AGRICULTURAL MARKETING Government of West Bengal LIST OF MARKETS Kolkata District Sl. No. Name of Markets Block/Municipality Page No. 1 A B - A C Market K M C 1 2 A E Market - do - 2 3 Ahiritola Bazar - do - 3 4 Akhra Fatak Bazar - do - 4 5 Allah Bharosha Bazar - do - 5 6 Amiya Babur Bazar - do - 6 7 Anath Nath Deb Bazar - do - 7 8 Ashu Babur Bazar - do - 8 9 Azadgarh Bastuhara Samity Bazar - do - 9 10 B. K. Pal ( Hat Khola Bazar) - do - 10 11 B. N. R. Daily Market - do - 11 12 Babu Bazar Market - do - 12 13 Babur Bazar - do - 13 14 Badartala Bazar - do - 14 15 Bagbazar Market - do - 15 16 Bagha Jatin Bazar - do - 16 17 Bagmari Bazar - do - 17 18 Baithak Khana Bazar - do - 18 19 Bakultala Bazar - do - 19 20 Ballygunge Station Bazar - do - 20 21 Bantala Natun Bazar - do - 21 22 Bantala Natun Bazar Hat - do - 22 23 Barisha Super Market - do - 23 24 Bartala Bazar - do - 24 25 Basdroni Bazar - do - 25 26 Bastu Hara Bazar - do - 26 27 Behala Laxmi Puratan Bazar - do - 27 28 Behala Natun Bazar - do - 28 29 Belgachia Bazar - do - 29 30 Bengali Bazar - do - 30 31 Bibi Bazar - do - 31 32 Bijoygarh Bazar - do - 32 33 Bowbazar Chhana Patty - do - 33 34 Bowbazar Market - do - 34 35 Burman Market - do - 35 36 Buro Shibtala Bazar - do - 36 37 Charu Market Bazar - do - 37 38 Chetla Bazar - do - 38 39 Chetla K. -

Disaster Management

ACTION PLAN TO MITIGATE FLOOD, CYCLONE & WATER LOGGING 2017 THE KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION 1 2 ESSENTIAL INFORMATION INCLUDING ACTION PLANS ARE MENTIONED UNDER FOLLOWING HEADS Sl No Item Page A Disaster Management – Introduction 5 B Important Activities of KMC in 11 connection with the Disaster Management C Major Water Logging Pockets 15 D Deployment of KMC Mazdoor at Major 29 Water Logging Pockets E Arrangement all Parks & Square 39 Development required removal of uprooting trees trimining at trees F List of the Sewerage and Drainage 45 Pumping Stations and deployment of temporary portable pumps during monsoon G Emergency arrangement during the 77 ensuing Nor’wester/Rainy season in the next few months of 2017 (Mpl. Commr. Circular No 11 of 2017-18 Dated 06/05/2017) H List of the roads where cleaning of G. 97 Ps. mouths /sweeping of roads will be made twice in a day by S.W.M. Department I Essential Telephone Numbers 107 3 4 A. DISASTER MANAGEMENT – INTRODUCTION The total area under Kolkata Municipal Corporation (KMC) is about 204.75 Sq. Km. which is divided into 16 Boroughs from Ward No-1 to Ward No- 144. The total population of the KMC area as per 2001 Census is about 4.6 million. Moreover, the floating population of the city is about 6 million. They are coming to this city for their livelihood from the outskirt and suburbs of the city of Kolkata i.e. City of Joy. From the experience regarding the water logging/flood condition during rainy season for the last few years, the KMC authority felt to publicize the disaster management plan as well as disaster management system for the benefit of the citizens, local representatives, State Govt. -

Religious Practices and the Preservation of Chinese-Indian Identity Among the Chinese Community of Kolkata

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences Vol. 7 Issue 12, December 2017, ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Journal Homepage: http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories Indexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A., Open J-Gage as well as in Cabell’s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A Religious Practices and the Preservation of Chinese-Indian Identity among the Chinese Community of Kolkata * Debarchana Biswas _____________________________________________________________________________________ Abstract _______________________________ _____________________________________________________ The Chinese community of a Kolkata has been settled in India more than two centuries. The relationship to the host society and to the authorities, particularly the dominant host culture, has gone through different stages with different forms. In the nineteenth century the Chinese community of Kolkata had established several Chinese temples. This study argues that the impact established by the Chinese community of Kolkata particularly on their religious practices is just unique to observe. It examines the adoration ofAtchew, Tianhou and goddess Kali added a new dimension or extent to their cultural life that creates a bond to both their Chinese heritage they carried and the place they live. Thus this study perhaps will be able to focus on how the Chinesecommunity safeguarding their age old heritage and identity which they carry forward. The study reveals how these unique practices show the process of acculturation and the creation of a new mixed Chinese–Indian identity.Thus this study will perhaps contribute to the field of social geography not only by helping to understand the multicultural dynamics of Kolkata, but also, will definitely find a concrete way to shape this ethnic enclave community. -

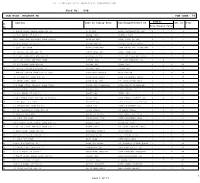

Ward No: 048 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79

BPL LIST-KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION Ward No: 048 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79 Member Sl Address Name of Family Head Son/Daughter/Wife of BPL ID Year No Male Female Total 1 2 NABIN CHAND BARAL LANE KOL-12 AJOY DEY LATE CHITTARANJAN DEY 2 4 6 1 2 12 P C BARAL ST KOL-12 ALAKA PAUL PRAKASH PAUL 1 1 2 2 3 22/D RAM KANI ADHIKARY LANE KOL-12 ALOK KR DEY LATE DULAL CH DEY 2 1 3 3 4 12 P C BARAL ST KOL-12 ALPANA MAITY KARTIC CHANDRA MAITY 0 1 1 4 5 8 GOUR DEY LANE AMIT SRIVASTAV LATE MADAN LAL SRIVASTAV 1 2 3 6 6 30 SHASHI BHUSAN DEY ST ANGUR BALA DAS LATE JITEN DAS 0 1 1 8 7 3/1 RAM BANARJEE LANE KOL 12 ANIRBAN DUTTA LT BIJOY BHUSHAN DUTTA 2 1 3 10 8 14/1 SRI GOPAL MULLICK LANE ANJALI DAS LT. SHIV CHANDRA DAS 1 4 5 11 9 26 N.C.BORAL LANE,KOL-12 ANJALI DAS GOPAL DAS 1 1 2 12 10 21 HARISH SIKDAR PATH,KOL-12 ANJANA PAUL UTTAM PAUL 2 2 4 13 11 5 HARISH SIKDAR PATH KOL-12 2NDL ANNAPURNA HALDAR BULU HALDAR 2 2 4 14 12 4C CHUNAPUKUR LANE KOL-12 ANNAPURNA NANDI LATE BISWANATH NANDI 1 3 4 15 13 16 NETAI BABU LANE ANNAPURNA PAUL LT. HARISADHAN PAUL 0 1 1 16 14 4/1 SREE GOPAL MALLICK LANE KOL12 APARAJITA MUKHERJEE LATE RANJIT MUKHERJEE 0 1 1 19 15 13 P C BORAL STREET APARNA DAS LATE RANJAN DAS 0 2 2 20 16 23 P C BARAL ST KOL-12 ARATI DAS JATAI DAS 0 1 1 22 17 8/1B CHAMPA TALA 1ST BYE LN KOL-12 ARATI DEY LATE NEMAI CHANDRA DEY 2 2 4 23 18 11/3A GOUR DEY LANE ARCHANA ROY LATE BIBHUTI BHUSAN ROY 0 1 1 26 19 13 CHUNAPUKUR LANE KOL-12 ASHOK DAS LATE RADHANATH DAS 1 2 3 29 20 26 DR JAGABANDHU LANE KOL 12 ASHOK GORAI LT MANIK GORAI 1 0 1 30 21 5 RAM BHUJAN LANE ASHOK KR DUTTA LATE GOKUL KR DUTTA 1 2 3 31 22 12 GOUR DEY LANE AUSTO BALA JANA LATE KASHINATH JANA 2 3 5 32 23 28/1 NABIN CHAND BORAL LANE KOL-12 BABITA SHAW RAJENDRA SHAW 5 3 8 34 24 3/3B SRI GOPAL MALLICK LANE KOL 12 ANIMA GUIN LT GOPAL CHANDRA GAIN 2 1 3 35 25 1 NETAI BABU LANE KOL-12 BABYDEBI MAHATO ARUN MAHATO 3 1 4 36 26 30 SASHI BHUSAN DEY,KOL-12 BALARAM SUTAR LT. -

Supplementary List of BPL Households 2013-14 049 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79 Ward

Supplementary List of BPL Households Ward No: 049 2013-14 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79 Member Sl Address Name of Family Head Son/Daughter/Wife of BPL ID No Male Female Total 1 11 ,BAITHAKKHANA 1ST LANE ,. ,700009 ABHISHEK SETH SAMBHU NATH SETH 2 1 3 710 2 162/1 ,B.B. GANGULY ST. ,. ,700012 AJAY SONKAR LT. HARILAL SONKAR 1 0 1 711 3 162/1 ,BIPIN BEHARI GANGULY STREET ,NAPIT BAGAN ,700001 ANITA BERA LATE PROFULLA CH BERA 4 5 9 712 4 162/1 ,B.B. GANGULY ST. ,. ,700012 APURBA BISWAS LT. NIRANJAN BISWAS 1 1 2 713 5 4/4A ,RAJA RAM MOHAN ROY SARANI ,AMHERST ST ,700009 ARUN MANNA LT. NANDA LAL MANNA 2 1 3 714 6 20 ,RAJ CHANDRA SEN LANE ,SEALDAH ,700009 ASHIMA KUNDU LT. MAKHAL CH. KUNDU 0 2 2 715 7 36/1 ,M G ROAD ,SEALDAH ,700009 ASHOK DAS LT. GANDHI DAS 3 1 4 716 8 162/1 ,B.B. GANGULY ST. ,. ,700012 ASHOKE SONKAR SUKHLAL SONKAR 1 4 5 717 9 156 ,B. B. GANGULY ST. ,BAITHAK KHANA ,700012 ASNI KUMAR SINGH LT. RAM DAYAL SINGH 3 1 4 718 10 10 ,BAITTAK KHANA ROAD ,SEALDAH ,700009 ASTAMI NASKAR LT. DAMADAR NASKAR 1 3 4 719 11 21 ,RAJANI GUPTA ROW ,SEALDAH ,700009 BABLU NAG LT. SUSHIL CH. NAG 1 1 2 720 12 88 ,AKHIL MISTRI LANE KOLKATA 9 ,SEALDAH ,700009 BAIDYA NATH DUTTA LATE CHINTA MONI DUTTA 1 1 2 721 13 107 B ,AKHIL MISTRI LANE KOLKATA 9 ,SEALDAH ,700009 BIBEKANANDA DUTTA LT MADAN GOPAL DUTTA 3 1 4 722 14 162/1/H/3 ,B.B.GANGULY STREET ,. -

SL NO Name Address Contact No VILL- RAMNARAYANPUR, P.O- RAGHUNATHPUR, 1 A

SL NO Name Address Contact No VILL- RAMNARAYANPUR, P.O- RAGHUNATHPUR, 1 A. BANDYOPADHYAY & CO BASIRHAT, DIST- NORTH 24 PARGANAS, PIN- 9433074874 743428 DEORA BHAWAN, 3, PRATAP GHOSH LANE, GR FL, 2 S.B. JHA & CO 9831242659, 8617219868 KOLKATA-700007 3 KEDIA KUSUM & ASSOCIATES 30, MADAN CHATTERJEE LANE, KOLKATA-700007 9831841686, 9830141686 1, NETAJI SUBAS ROAD, 2ND , FL, KOLKATA- 4 MUKHERJEE DEBDAS & CO 9830980492 700001 10,OLD POST OFFICE STREET, 3RD RL, R NO-76, 5 B.N.RAY & CO 9830201663 KOLKATA-700001 3A, SURENDRA MOHAN GHOSH SARANI ( 6 MAROTI & CO FORMERLY MANGOE LANE,) 1ST FL, SOUTH-WEST- 9831039461, 03322107378 SIDE, KOLKATA-700001 33/1, N S ROAD, MARSHAL HOUSE, 7TH FL, R NO- 7 E CHHAPARIA & ASSOCIATES 9883534321 748, KOL-700001 33/1, N S ROAD, MARSHAL HOUSE, 7TH FL, R NO- 8 A. CHHAPARIA & ASSOCIATES 988353421 748, KOL-700001 BLOCK-A. 3RD FL. MERCANTILE BUILDING, 9/12. 9 N L BEDIAL & ASSOCIATES 9331012644 03322000000 LAL BAZAR STREET KOLP700001 10 AMITAVA BANIK & ASSOCIATES 409 BANTICK STREET, KOL-700069 9831070358 94330151978 11 A.K.KUNDU & CO 24 N.S. ROAD 1ST FL, BANKURA -722101 9474561740 03242255443 12 U K GUPTA & CO 65/1, SUKANTA SARANI KOL-700063 9830311703 13 K.SARBADHIKARI &CO. 157C,LENIN SARANI, KOLKATA 700 013 2215 3205/2215 5341 59,BIPLABI ANILUKCHANDRA STREET.1ST,FLOOR, 14 A.TORAB & CO. 033 2235-2345, KOLKATA 700 072 SATYAPIRTALA LANE, P.O- CHINSURAH, DIST- 15 S.B. ROY & ASSOCIATES 9433429204 9432954600 HOOGHLY,712101 MODEL HOUSE, 2ND FLLOR, R NO- 28B, 40 16 B L & ASSOCIATES 8981466189 STRAND ROAD KOL-700001 swapnasree' Behind Tamluk Ghatal Bank) 17 P.P.