Slum Diversity in Kolkata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lions Clubs International

Lions Clubs International Clubs Missing a Current Year Club Officer (Only President, Secretary or Treasurer) as of July 08, 2010 District 322 B2 Club Club Name Title (Missing) 34589 SHYAMNAGAR President 34589 SHYAMNAGAR Secretary 34589 SHYAMNAGAR Treasurer 42234 KANCHRAPARA President 42234 KANCHRAPARA Secretary 42234 KANCHRAPARA Treasurer 46256 CALCUTTA WOODLANDS President 46256 CALCUTTA WOODLANDS Secretary 46256 CALCUTTA WOODLANDS Treasurer 61410 CALCUTTA EAST WEST President 61410 CALCUTTA EAST WEST Secretary 61410 CALCUTTA EAST WEST Treasurer 63042 BASIRHAT President 63042 BASIRHAT Secretary 63042 BASIRHAT Treasurer 66648 AURANGABAD GREATER Secretary 66648 AURANGABAD GREATER Treasurer 66754 BERHAMPORE BHAGIRATHI President 66754 BERHAMPORE BHAGIRATHI Secretary 66754 BERHAMPORE BHAGIRATHI Treasurer 84993 CALCUTTA SHAKESPEARE SARANI President 84993 CALCUTTA SHAKESPEARE SARANI Secretary 84993 CALCUTTA SHAKESPEARE SARANI Treasurer 100797 KOLKATA INDIA EXCHANGE GREATER President 100797 KOLKATA INDIA EXCHANGE GREATER Secretary 100797 KOLKATA INDIA EXCHANGE GREATER Treasurer 101372 DUM DUM GREATER President 101372 DUM DUM GREATER Secretary 101372 DUM DUM GREATER Treasurer 102087 BARASAT CITY President 102087 BARASAT CITY Secretary 102087 BARASAT CITY Treasurer 102089 KOLKATA VIP PURWANCHAL President OFF0021 Run Date: 7/8/2010 11:44:11AM Page 1 of 2 Lions Clubs International Clubs Missing a Current Year Club Officer (Only President, Secretary or Treasurer) as of July 08, 2010 District 322 B2 Club Club Name Title (Missing) 102089 KOLKATA VIP -

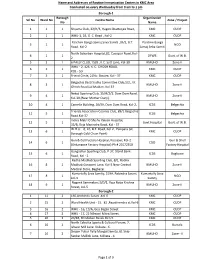

Name and Addresses of Routine Immunization Centers in KMC Area

Name and Addresses of Routine Immunization Centers in KMC Area Conducted on every Wednesday from 9 am to 1 pm Borough-1 Borough Organization Srl No Ward No Centre Name Zone / Project No Name 1 1 1 Shyama Club, 22/H/3, Hagen Chatterjee Road, KMC CUDP 2 1 1 WHU-1, 1B, G. C. Road , Kol-2 KMC CUDP Paschim Banga Samaj Seva Samiti ,35/2, B.T. Paschim Banga 3 1 1 NGO Road, Kol-2 Samaj Seba Samiti North Subarban Hospital,82, Cossipur Road, Kol- 4 1 1 DFWB Govt. of W.B. 2 5 2 1 6 PALLY CLUB, 15/B , K.C. Sett Lane, Kol-30 KMUHO Zone-II WHU - 2, 126, K. C. GHOSH ROAD, 6 2 1 KMC CUDP KOL - 50 7 3 1 Friend Circle, 21No. Bustee, Kol - 37 KMC CUDP Belgachia Basti Sudha Committee Club,1/2, J.K. 8 3 1 KMUHO Zone-II Ghosh Road,Lal Maidan, Kol-37 Netaji Sporting Club, 15/H/2/1, Dum Dum Road, 9 4 1 KMUHO Zone-II Kol-30,(Near Mother Diary). 10 4 1 Camelia Building, 26/59, Dum Dum Road, Kol-2, ICDS Belgachia Friends Association Cosmos Club, 89/1 Belgachia 11 5 1 ICDS Belgachia Road.Kol-37 Indira Matri O Shishu Kalyan Hospital, 12 5 1 Govt.Hospital Govt. of W.B. 35/B, Raja Manindra Road, Kol - 37 W.H.U. - 6, 10, B.T. Road, Kol-2 , Paikpara (at 13 6 1 KMC CUDP Borough Cold Chain Point) Gun & Cell Factory Hospital, Kossipur, Kol-2 Gun & Shell 14 6 1 CGO (Ordanance Factory Hospital) Ph # 25572350 Factory Hospital Gangadhar Sporting Club, P-37, Stand Bank 15 6 1 ICDS Bagbazar Road, Kol - 2 Radha Madhab Sporting Club, 8/1, Radha 16 8 1 Madhab Goswami Lane, Kol-3.Near Central KMUHO Zone-II Medical Store, Bagbazar Kumartully Seva Samity, 519A, Rabindra Sarani, Kumartully Seva 17 8 1 NGO kol-3 Samity Nagarik Sammelani,3/D/1, Raja Naba Krishna 18 9 1 KMUHO Zone-II Street, kol-5 Borough-2 1 11 2 160,Arobindu Sarani ,Kol-6 KMC CUDP 2 15 2 Ward Health Unit - 15. -

Kolkata the Gazette

Registered No. WB/SC-247 No. WB(Part-III)/2021/SAR-9 The Kolkata Gazette Extraordinary Published by Authority SRAVANA 4] MONDAY, JUly 26, 2021 [SAKA 1943 PART III—Acts of the West Bengal Legislature. GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL LAW DEPARTMENT Legislative NOTIFICATION No. 573-L.—26th July, 2021.—The following Act of the West Bengal Legislature, having been assented to by the Governor, is hereby published for general information:— West Bengal Act IX of 2021 THE WEST BENGAL FINANCE ACT, 2021. [Passed by the West Bengal Legislature.] [Assent of the Governor was first published in the Kolkata Gazette, Extraordinary, of the 26th July, 2021.] An Act to amend the Indian Stamp Act, 1899, in its application to West Bengal and the West Bengal Goods and Services Tax Act, 2017. WHEREAS it is expedient to amend the Indian Stamp Act, 1899, in its application to 2 of 1899. West Bengal and the West Bengal Goods and Services Tax Act, 2017, for the purposes West Ben. Act and in the manner hereinafter appearing; XXVIII of 2017. It is hereby enacted in the Seventy-second Year of the Republic of India, by the Legislature of West Bengal, as follows:— Short title and 1. (1) This Act may be called the West Bengal Finance Act, 2021. commencement. (2) Save as otherwise provided, this section shall come into force with immediate effect, and the other provisions of this Act shall come into force on such date, with prospective or retrospective effect as required, as the State Government may, by 2 THE KOLKATA GAZETTE, EXTRAORDINARY, JUly 26, 2021 PART III] The West Bengal Finance Act, 2021. -

Purchaser DEED OF

Siddhant Vincom LLP & Ors Owners And M/S Surreal Realty LLP Developer And _________________________ Purchaser DEED OF CONVEYENCE RE: Flat No. ______ , _ ___Floor, at“ WINDSOR THE RESIDENCE ” at 170D Picnic Garden Road, Kolkata 700039. Meharia Reid & Associates 9, Old Post Office Street, Ground Floor Kolkata 700001 THIS DEED OF CONVEYENCE made this _____ day of __________ 2018 BETWEEN M/S Sidhant Fincom Private Limited (PAN: AAECS4870R) and M/S Palak Mercantile Private Limited (PAN: AABCP6852H), both companies formed under the Companies Act of 1956 and having their registered offices at 40, Strand Road, P. O. & P. S. Burrabazar Kolkata 700001, represented by its Constituted attorney Mr. Manoj Poddar, son of Late Mr. C. K. Poddar, residing at 5A, Old Ballygunge, 2nd Lane, P. S. Karaya, P. O. Ballygunge, Kolkata 700019 (PAN: AERPP5136P), hereinafter referred to as the ‘OWNERS’ of the FIRST PART; AND M/s Surreal Realty LLP (PAN: ACWFS7460C), a Limited Liability Partnership formed and governed under the LLP Act of 2008 and having its registered office at Janki Mansion, 2nd Floor, 77/1A, P.O & P.S-Park Street, Kolkata 7000016, represented by Designated partner Mr. Manoj Poddar, son of Late Mr. C. K. Poddar, residing at 5A, Old Ballygunge, 2nd Lane, P. S. Karaya, P. O. Ballygunge, Kolkata 700019 (PAN: AERPP5136P)hereinafter referred to as the ‘DEVELOPER’ (which expression shall unless excluded by or repugnant to the subject or context shall mean and include its successor and/or successors in office) of the SECOND PART; AND ________________________ (PAN: ____________________) son of _______________________ residing at __________________ By Religion: Hindu, Nationality: Indian, Occupation: Business P. -

List of Polling Premises Under 163 – Entally Assembly Constituency

List of Polling Premises under 163 – Entally Assembly Constituency K.M. Borou Name & Address of the Name of the Polling Address of the Polling Polling Stations C. Police Sl. No of PS gh Polling Premises Premises Premises Attached Ward Station No. No Entally Academy , 23, 23, Girish Chandra Bose 1 Girish Chandra Bose Road, Entally Academy 1,2,3,4,5 5 54 VI Entally Road, Kolkata – 14 Kolkata – 14 Taltala Dispensary & Ward 54 Health Unit,3, Girish Taltala Dispensary & 3, Girish Chandra Bose 2 6,7 2 54 VI Entally Chandra Bose Road, Ward 54 Health Unit Road, Kolkata-14 Kolkata-14 KMC Health Unit & Community Hall ,3, Girish KMC Health Unit & 3, Girish Chandra Bose 3 8,9,10,11,13 5 54 VI Entally Chandra Bose Road, Community Hall Road, Kolkata-14 Kolkata-14 Taltala Dispensary & Ward 54 Health Unit, 3, Girish Taltala Dispensary & 3, Girish Chandra Bose 4 12 ,14, 15 3 54 VI Entally Chandra Bose Road, Ward 54 Health Unit Road, Kolkata-14 Kolkata-14 K.M.C.P School ,35, Satish 35, Satish Chandra Beniapuk 5 Chandra Mukhopadhyay K.M.C.P School Mukhopadhyay Sarani, 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 4 54 VI ur Sarani, Kolkata- 14 Kolkata- 14 Anjuman Girls Higher Secondary Anjuman Girls Higher 31,Mufidul Islam Lane, Beniapuk 6 20, 21 , 22 , 23 4 54 VI School,31,Mufidul Islam Secondary School Kolkata- 14 ur Lane, Kolkata- 14 Anjuman Mufidul Islam 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , Anjuman Mufidul Islam 20, Noor Ali Lane, Beniapuk 7 Girls High School,20,Noor 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 9 54 VI Girls High School Kolkata-14 ur Ali Lane , Kolkata-14 32 K.M. -

Abstract Ward No 58 Is an Underprivileged Area of Kolkata

6 Historical Background And Socio-Economic Condition Of Ward No 58 Under Kolkata Municipality Kuhumita Bachhar Assistant Teacher Sanat Roy Chowdhury Institution Kolkata Abstract Ward no 58 is an underprivileged area of kolkata. Where the other part of kolkata is developing from every aspect like culture, literature, behavior, economic condition but this area remains the same. Considering this mysterious situation, small step has taken to search its reason from past and tried to present their recent socio-economic condition, and hope for their betterment. Key word: socio condition, economic condition Introduction-To explore the history of modern Kolkata, we trace back to1698- when The British leased three villages – Gobindapur, Sutanuti, Kolkata from Subarna Roychowdhury for Rs 1300 a year, and incepted our beloved Kolkata. In late 17th century,an Englishman called Job Charnock established Kolkata from three sleepy hamlet – Sutanuti, Gobindapur and Kolkata. Kolkata Municipal Corporation was established to improve and run the city properly. Its main work was to build and maintain roads, drains, in proper way. Taxes were levied on housing, lighting, and vehicle. Now the mega city is divided into 144 administrative wards that are grouped into 16 boroughs. Here I am going to discuss about 58 no wards under Kolkata Municipal Corporation. History of original residents – Before discussing about the socio-economic condition of residents of this ward we have to know why their previous generation had come here and started living permanently. The leather industry took roots in the eastern part of Calcutta in Dhapa,Tangra,Topsia and Tiljala. These are marshy areas in which are found a good number of big tanneries as well as small ones. -

Fffiffi @ North 24 Parganas, Barasat

Government of West Bengal eE+ District Health & Family Welfare Samiti &-i, of Health office of the Chief Medical Officer fffiffi @ North 24 Parganas, Barasat Dated: ba,s,IL Memo No. DH & FWS/NHM/2016/ ltS l ORDER HMl2ot6lL030' dated 11'08'16 to the recruitment notification no' DH&FWS/N ln reference (Full rime) under NUHM for serected for the post of Medicar officer the foilowing candidates are hereby of L7 on a consolidated monthly remuneration purely contract basis for a period upto 31'03' uPHCs on Bidhannagar Municipal onry and posted at concerned Municipa,ty / Rs.40,000/_ (Rupees Forty Thousand) Corporation enlisted hereunder- the Place of Posting sl. Application Name of Address candidate No' ID Ashoknagar S.r"A. Sarani, Nibedita Park, PO- Das MuniciPalitY 1 FTMO-042 Dr. Sukanta urirlerrnrrr PS- Barasat, KolL27 lSl' Baranagar 42" S.ti; Sen Nagar,Baranagar, Dr. Partha Sarathl MuniciPalitY 2 FTMO-004 Kol-108 Sardar Baranagar Majumdar 2713ll P.W.D Road, Kol-35 MuniciPalitY 3 FTMO-006 Dr. JaydeeP CHARAK DANGA LAT Baranagar ROAD,' DARSAN,APARTM ENT,F DAS N- MuniciPalitY 4 FTMO-034 DR.KOUSHIK NO-GO2,UTTARPARA,HOOGH LY,PI 712258 Barasat Milan PallY, Hrldaypur,6ar ir5dL, MuniciPalitY 5 il;;l;;haLatasarker 1A Dcc Kal-1)7 Barasat Saradamani Road, NaoaPattY, RoY MuniciPalitY Dr. Parijat Bikash Darac2t Nl?4 Pss. Kol-700126_ 6 FTMO-009 uql qJqr, r!- ! ' o-, -- Barasat Saroj Park, Taki Road, Barasat- MuniciPalitY 7 FTMO-055 Dr. Gita RoY -7n,n.1)L Basirhat DlD32l4 Bina RPPI' t:roulru rruur' MuniciPalitY s I FTMo-026 Dr. -

Inner-City and Outer-City Neighbourhoods in Kolkata: Their Changing Dynamics Post Liberalization

Article Environment and Urbanization ASIA Inner-city and Outer-city 6(2) 139–153 © 2015 National Institute Neighbourhoods in Kolkata: of Urban Affairs (NIUA) SAGE Publications Their Changing Dynamics sagepub.in/home.nav DOI: 10.1177/0975425315589157 Post Liberalization http://eua.sagepub.com Annapurna Shaw1 Abstract The central areas of the largest metropolitan cities in India are slowing down. Outer suburbs continue to grow but the inner city consisting of the oldest wards is stagnating and even losing population. This trend needs to be studied carefully as its implications are deep and far-reaching. The objective of this article is to focus on what is happening to the internal structure of the city post liberalization by highlighting the changing dynamics of inner-city and outer-city neighbourhoods in Kolkata. The second section provides a brief background to the metropolitan region of Kolkata and the city’s role within this region. Based on ward-level census data for the last 20 years, broad demographic changes under- gone by the city of Kolkata are examined in the third section. The drivers of growth and decline and their implications for livability are discussed in the fourth section. In the fifth section, field observations based on a few representative wards are presented. The sixth section concludes the article with policy recommendations. 加尔各答内城和外城社区:后自由主义化背景下的动态变化 印度最大都市区中心地区的发展正在放缓。远郊持续增长,但拥有最老城区的内城停滞不 前,甚至出现人口外流。这种趋势需要仔细研究,因为它的影响是深刻而长远的。本文的目 的是,通过强调加尔各答内城和外城社区的动态变化,关注正在发生的后自由化背景下的城 市内部结构。第二部分提供了概括性的背景,介绍了加尔各答的大都市区,以及城市在这个 区域内的角色。在第三部分中,基于过去二十年城区层面的人口普查数据,研究考察了加尔 各答城市经历的广泛的人口变化。第四部分探讨了人口增长和衰退的推动力,以及它们对于 城市活力的影响。第五部分展示了基于几个有代表性城区的实地观察。第六部分提出了结论 与政策建议。 Keywords Inner city, outer city, growth, decline, neighbourhoods 1 Professor, Public Policy and Management Group, Indian Institute of Management Calcutta, Kolkata, India. -

The Great Calcutta Killings Noakhali Genocide

1946 : THE GREAT CALCUTTA KILLINGS AND NOAKHALI GENOCIDE 1946 : THE GREAT CALCUTTA KILLINGS AND NOAKHALI GENOCIDE A HISTORICAL STUDY DINESH CHANDRA SINHA : ASHOK DASGUPTA No part of this publication can be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the author and the publisher. Published by Sri Himansu Maity 3B, Dinabandhu Lane Kolkata-700006 Edition First, 2011 Price ` 500.00 (Rupees Five Hundred Only) US $25 (US Dollars Twenty Five Only) © Reserved Printed at Mahamaya Press & Binding, Kolkata Available at Tuhina Prakashani 12/C, Bankim Chatterjee Street Kolkata-700073 Dedication In memory of those insatiate souls who had fallen victims to the swords and bullets of the protagonist of partition and Pakistan; and also those who had to undergo unparalleled brutality and humility and then forcibly uprooted from ancestral hearth and home. PREFACE What prompted us in writing this Book. As the saying goes, truth is the first casualty of war; so is true history, the first casualty of India’s struggle for independence. We, the Hindus of Bengal happen to be one of the worst victims of Islamic intolerance in the world. Bengal, which had been under Islamic attack for centuries, beginning with the invasion of the Turkish marauder Bakhtiyar Khilji eight hundred years back. We had a respite from Islamic rule for about two hundred years after the English East India Company defeated the Muslim ruler of Bengal. Siraj-ud-daulah in 1757. But gradually, Bengal had been turned into a Muslim majority province. -

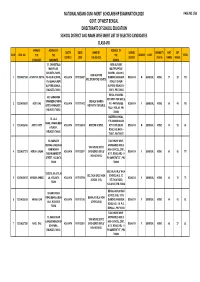

Kolkata Merit List

NATIONAL MEANS‐CUM ‐MERIT SCHOLARSHIP EXAMINATION,2020 PAGE NO.1/63 GOVT. OF WEST BENGAL DIRECTORATE OF SCHOOL EDUCATION SCHOOL DISTRICT AND NAME WISE MERIT LIST OF SELECTED CANDIDATES CLASS‐VIII NAME OF ADDRESS OF ADDRESS OF QUOTA UDISE NAME OF SCHOOL DISABILITY MAT SAT SLNO ROLL NO. THE THE THE GENDER CASTE TOTAL DISTRICT CODE THE SCHOOL DISTRICT STATUS MARKS MARKS CANDIDATE CANDIDATE SCHOOL 7/1, CHANDITALA NEW ALIPORE MAIN ROAD, MULTIPURPOSE KOLKATA-700053, SCHOOL, 23A/439/1, NEW ALIPORE 1 123204307048 ACHINTYA DUTTA PO- NEW ALIPORE, KOLKATA 19170108427 DIAMOND HARBOUR KOLKATA M GENERAL NONE 57 53 110 MULTIPURPOSE SCHOOL PS- BEHALA,NEW ROAD, P.O-NEW ALIPORE,BEHALA , ALIPORE, KOLKATA - KOLKATA 700053 700073, PIN-700053 BEHALA SHARDA 6/D, SARADAMA VIDYAPITH FOR GIRLS, UPANIBESH,PARNA BEHALA SHARDA 2 123204306005 ADITI DAS KOLKATA 19170113412 PO - PARNASREE KOLKATA F GENERAL NONE 60 49 109 SREE,PARNASREE , VIDYAPITH FOR GIRLS PALLY, KOL-60, PIN- KOLKATA 700060 700060 MODERN SCHOOL, TILJALA 17B, MANORANJAN ROAD,TANGRA,BENI 3 123204306180 ADITYA ROY KOLKATA 19170106510 MODERN SCHOOL ROY CHOUDHURI KOLKATA M GENERAL NONE 54 35 89 A PUKUR , ROAD, KOLKATA - KOLKATA 700046 700017, PIN-700017 3A RAMNATH TAKI HOUSE GOVT. BISWAS LANE,RAJA SPONSORED GIRLS' TAKI HOUSE GOVT. RAM MOHAN HIGH SCHOOL, 299C, 4 123204307075 ADRIJA BASAK KOLKATA 19170103911 SPONSORED GIRLS' KOLKATA F GENERAL NONE 61 56 117 SARANI,AMHERST A.P.C. ROAD, KOL - 9 HIGH SCHOOL STREET , KOLKATA PO AMHERST ST., PIN- 700009 700009 BELTALA GIRLS' HIGH 30/25,TILJALA,TILJA BELTALA GIRLS' HIGH SCHOOL (H.S), 17, 5 123204306135 AFREEN AHMED LA , KOLKATA KOLKATA 19170107506 KOLKATA F GENERAL NONE 44 31 75 SCHOOL (H.S) BELTALA ROAD, 700039 KALIGHAT, PIN-700026 BEHALA GIRLS HIGH 30 BARIK PARA SCHOOL(H.S), 337/4, ROAD,BEHALA,BEH BEHALA GIRLS HIGH 6 123204306129 AHANA DAS KOLKATA 19170112202 DIAMOND HARBOUR KOLKATA F GENERAL NONE 49 43 92 ALA , KOLKATA SCHOOL(H.S) ROAD, KOL - 34 P.O. -

People Without History

People Without History Seabrook T02250 00 pre 1 24/12/2010 10:45 Seabrook T02250 00 pre 2 24/12/2010 10:45 People Without History India’s Muslim Ghettos Jeremy Seabrook and Imran Ahmed Siddiqui Seabrook T02250 00 pre 3 24/12/2010 10:45 First published 2011 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010 www.plutobooks.com Distributed in the United States of America exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of St. Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010 Copyright © Jeremy Seabrook and Imran Ahmed Siddiqui 2011 The right of Jeremy Seabrook and Imran Ahmed Siddiqui to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7453 3114 0 Hardback ISBN 978 0 7453 3113 3 Paperback Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data applied for This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Designed and produced for Pluto Press by Chase Publishing Services Ltd, 33 Livonia Road, Sidmouth, EX10 9JB, England Typeset from disk by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England Simultaneously printed digitally by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham, UK and Edwards Bros in the USA Seabrook T02250 00 pre 4 24/12/2010 10:45 Contents Acknowledgements vi Introduction 1 1. -

Appendix a the City of Kolkata

Appendix A The City of Kolkata This appendix provides a brief description about the city of Kolkata—the study area of the research documented in this book. A.1 Introduction The city of Kolkata (formerly Calcutta) is more than 300 years old and it served as the capital of India during the British governance until 1911. Kolkata is the capital of the Indian state of West Bengal; and is the main business, commercial, and financial hub of eastern India and the north-eastern states. It is located in the eastern India at 22° 330N88° 200E on the east bank of River Hooghly (Ganges Delta) (Fig. A.1) at an elevation ranging from 1.5 to 9 m (SRTM image, NASA, Feb 2000). A.2 Administrative Structure The civic administration of Kolkata is executed by several government agencies, and consists of overlapping structural divisions. At least five administrative definitions of the city are available: 1. Kolkata Central Business District: hosts the core central part of Kolkata and contains 24 wards of the municipal corporation. 2. Kolkata District: contains the center part of the city of Kolkata. It is the jurisdiction of the Kolkata Collector. 3. Kolkata Police Area: the jurisdiction of the Kolkata Police covers the KMS and some adjacent areas as well.1 1 The service area of Kolkata Police was 105 km2 as of 31st Aug 2011. The area has been extended from 1st Sep 2011 to cover the entire KMC and some adjacent areas. B. Bhatta, Urban Growth Analysis and Remote Sensing, SpringerBriefs in Geography, 89 DOI: 10.1007/978-94-007-4698-5, Ó The Author(s) 2012 90 Appendix A: The City of Kolkata Fig.