Transforming Kolkata: a Partnership for a More Sustainable, Inclusive, and Resilient City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

House Owners Checkoints to Let / Sublet / Rent Accommodation

Memo.No.86/ICA/NB/PN Dated: 28/02/2014 Kolkata Police Notification to House Owners In view of the situation prevailing in the areas of Police Stations specified in the Schedule appended to this order, it is apprehended that terrorist /anti-social elements may seek hideouts in the residential areas of the said Police Stations and there is every likelihood of breach of the peace and disturbance of public tranquility and also there is grave danger to human life and safety and injury to public property on that account. And whereas it is necessary that some checks should be put on land lords/ tenants so that terrorist/anti-social elements in the guise of tenants may not cause riots and damage public property etc. and that immediate action is necessary for the prevention of the same. Kolkata Police do hereby order that no land-lord/owner/person whose house property falls under the jurisdiction of area of Police Stations specified in the Schedule appended to this order, shall let/sublet/rent out any accommodation to any person unless and until he/she has furnished the particulars of the said tenant(s) as per Proforma in Schedule-11 to the Officer-in-charge of the Police Station conc erned. All persons who intend to take accommodation on rent shall inform in writing in this regard to the Officer-in-Charge of the Police Station concerned in whose jurisdiction the premises fall. The persons dealing in property business shall also inform in writing to the Officer-in-Charge of the Police Station concerned in whose jurisdiction the premises fall about the particulars of the tenants. -

Lions Clubs International

Lions Clubs International Clubs Missing a Current Year Club Officer (Only President, Secretary or Treasurer) as of July 08, 2010 District 322 B2 Club Club Name Title (Missing) 34589 SHYAMNAGAR President 34589 SHYAMNAGAR Secretary 34589 SHYAMNAGAR Treasurer 42234 KANCHRAPARA President 42234 KANCHRAPARA Secretary 42234 KANCHRAPARA Treasurer 46256 CALCUTTA WOODLANDS President 46256 CALCUTTA WOODLANDS Secretary 46256 CALCUTTA WOODLANDS Treasurer 61410 CALCUTTA EAST WEST President 61410 CALCUTTA EAST WEST Secretary 61410 CALCUTTA EAST WEST Treasurer 63042 BASIRHAT President 63042 BASIRHAT Secretary 63042 BASIRHAT Treasurer 66648 AURANGABAD GREATER Secretary 66648 AURANGABAD GREATER Treasurer 66754 BERHAMPORE BHAGIRATHI President 66754 BERHAMPORE BHAGIRATHI Secretary 66754 BERHAMPORE BHAGIRATHI Treasurer 84993 CALCUTTA SHAKESPEARE SARANI President 84993 CALCUTTA SHAKESPEARE SARANI Secretary 84993 CALCUTTA SHAKESPEARE SARANI Treasurer 100797 KOLKATA INDIA EXCHANGE GREATER President 100797 KOLKATA INDIA EXCHANGE GREATER Secretary 100797 KOLKATA INDIA EXCHANGE GREATER Treasurer 101372 DUM DUM GREATER President 101372 DUM DUM GREATER Secretary 101372 DUM DUM GREATER Treasurer 102087 BARASAT CITY President 102087 BARASAT CITY Secretary 102087 BARASAT CITY Treasurer 102089 KOLKATA VIP PURWANCHAL President OFF0021 Run Date: 7/8/2010 11:44:11AM Page 1 of 2 Lions Clubs International Clubs Missing a Current Year Club Officer (Only President, Secretary or Treasurer) as of July 08, 2010 District 322 B2 Club Club Name Title (Missing) 102089 KOLKATA VIP -

Capacity Building Programme

Capacity Building Programme Volume - XI Graded List of Heritage Buildings Grade-I, Grade-IIA & Grade-IIB Premises as on 25. 2. 2009 Kolkata Municipal Corporation 5, S. N. Banerjee Road Kolkata -700 013 EPABX - 2286-1000 (22 Lines) www.kolkatamycity.com FOREWORD 1. The Government of West Bengal, by a resolution No. 5584-UD/O/M/SB/S-22/96 dated 6th October 1997, constituted a Committee known as “Expert Committee on Heritage Buildings” to identify the heritage buildings and sites in Kolkata Municipal Corporation (KMC) area. The said Expert Committee submitted its final report to the State Government on 02.11.1998. The report was discussed in a meeting on 01.12.1998, which was presided over by the Hon’ble M.I.C., Home (Police) and I & CA Departments, and attended by, inter alia, the Hon’ble M.I.C., Urban Development Department and the Hon’ble Mayor of Kolkata; the Principal Secretary, Urban Development Department; the Secretary, Municipal Affairs Department; the Chief Executive Officer, KMDA etc. It was decided in the meeting that the list recommended by the Committee would be sent to KMC for the acceptance and for taking suitable actions towards the preservation and conservation of those heritage buildings/sites in terms of the KMC Act, 1980 (Amendment). The KMC accepted and adopted the report in principle. 2. Meanwhile, in 1997 the Chapter XXIIIA was inserted in the KMC Act 1980 for introducing a Chapter for preservation and conservation of the heritage buildings. The Chapter and the provisions therein are self-explanatory. 3. Thus, by 1998, KMC had two instrumentalities. -

Star Campaigners of Lndian National Congress for West Benqal

, ph .230184s2 $ t./r. --g-tv ' "''23019080 INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 24, AKBAR ROAD, NEW DELHI'110011 K.C VENUGOPAL, MP General Secretary PG-gC/ }:B U 12th March,2021 The Secretary Election Commission of lndia Nirvachan Sadan New Delhi *e Sub: Star Campaigners of lndian National Congress for West Benqal. 2 Sir, The following leaders of lndian National Congress, who would be campaigning as per Section 77(1) of Representation of People Act 1951, for the ensuing First Phase '7* of elections to the Legislative Assembly of West Bengat to be held on 2ffif M-arch br,*r% 2021. \,/ Sl.No. Campaiqners Sl.No. Campaiqners \ 1 Smt. Sonia Gandhi 16 Shri R"P.N. Sinqh 2 Dr. Manmohan Sinqh 17 Shri Naviot Sinqh Sidhu 3 Shri Rahul Gandhi 18 ShriAbdul Mannan 4 Smt. Priyanka Gandhi Vadra 19 Shri Pradip Bhattacharva w 5 Shri Mallikarjun Kharqe 20 Smt. Deepa Dasmunsi 6 ShriAshok Gehlot 21 Shri A.H. Khan Choudhary ,n.T 7 Capt. Amarinder Sinqh 22 ShriAbhiiit Mukheriee 8 Shri Bhupesh Bhaohel 23 Shri Deependra Hooda * I Shri Kamal Nath 24 Shri Akhilesh Prasad Sinqh 10 Shri Adhir Ranian Chowdhury 25 Shri Rameshwar Oraon 11 Shri B.K. Hari Prasad 26 Shri Alamqir Alam 12 Shri Salman Khurshid 27 Mohd Azharuddin '13 Shri Sachin Pilot 28 Shri Jaiveer Sherqill 14 Shri Randeep Singh Suriewala 29 Shri Pawan Khera 15 Shri Jitin Prasada 30 Shri B.P. Sinqh This is for your kind perusal and necessary action. Thanking you, Yours faithfully, IIt' I \..- l- ;i.( ..-1 )7 ,. " : si fqdq I-,. elS€ (K.C4fENUGOPAL) I t", j =\ - ,i 3o Os 'Ji:.:l{i:,iii-iliii..d'a !:.i1.ii'ji':,1 s}T ji}'iE;i:"]" tiiaA;i:i:ii-q;T') ilem€s"m} il*Eaacr:lltt,*e Ge rt r; l-;a. -

Metro Railway Kolkata Presentation for Advisory Board of Metro Railways on 29.6.2012

METRO RAILWAY KOLKATA PRESENTATION FOR ADVISORY BOARD OF METRO RAILWAYS ON 29.6.2012 J.K. Verma Chief Engineer 8/1/2012 1 Initial Survey for MTP by French Metro in 1949. Dum Dum – Tollygunge RTS project sanctioned in June, 1972. Foundation stone laid by Smt. Indira Gandhi, the then Prime Minister of India on December 29, 1972. First train rolled out from Esplanade to Bhawanipur (4 km) on 24th October, 1984. Total corridor under operation: 25.1 km Total extension projects under execution: 89 km. June 29, 2012 2 June 29, 2012 3 SEORAPFULI BARRACKPUR 12.5KM SHRIRAMPUR Metro Projects In Kolkata BARRACKPUR TITAGARH TITAGARH 10.0KM BARASAT KHARDAH (UP 17.88Km) KHARDAH 8.0KM (DN 18.13Km) RISHRA NOAPARA- BARASAT VIA HRIDAYPUR PANIHATI AIRPORT (UP 15.80Km) (DN 16.05Km)BARASAT 6.0KM SODEPUR PROP. NOAPARA- BARASAT KONNAGAR METROMADHYAMGRAM EXTN. AGARPARA (UP 13.35Km) GOBRA 4.5KM (DN 13.60Km) NEW BARRACKPUR HIND MOTOR AGARPARA KAMARHATI BISARPARA NEW BARRACKPUR (UP 10.75Km) 2.5KM (DN 11.00Km) DANKUNI UTTARPARA BARANAGAR BIRATI (UP 7.75Km) PROP.BARANAGAR-BARRACKPORE (DN 8.00Km) BELGHARIA BARRACKPORE/ BELA NAGAR BIRATI DAKSHINESWAR (2.0Km EX.BARANAGAR) BALLY BARANAGAR (0.0Km)(5.2Km EX.DUM DUM) SHANTI NAGAR BIMAN BANDAR 4.55KM (UP 6.15Km) BALLY GHAT RAMKRISHNA PALLI (DN 6.4Km) RAJCHANDRAPUR DAKSHINESWAR 2.5KM DAKSHINESWAR BARANAGAR RD. NOAPARA DAKSHINESWAR - DURGA NAGAR AIRPORT BALLY HALT NOAPARA (0.0Km) (2.09Km EX.DMI) HALDIRAM BARANAGAR BELUR JESSOR RD DUM DUM 5.0KM DUM DUM CANT. CANT 2.60KM NEW TOWN DUM DUM LILUAH KAVI SUBHAS- DUMDUM DUM DUM ROAD CONVENTION CENTER DUM DUM DUM DUM - BELGACHIA KOLKATA DASNAGAR TIKIAPARA AIRPORT BARANAGAR HOWRAH SHYAM BAZAR RAJARHAT RAMRAJATALA SHOBHABAZAR Maidan BIDHAN NAGAR RD. -

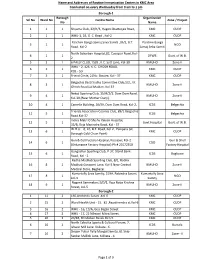

Name and Addresses of Routine Immunization Centers in KMC Area

Name and Addresses of Routine Immunization Centers in KMC Area Conducted on every Wednesday from 9 am to 1 pm Borough-1 Borough Organization Srl No Ward No Centre Name Zone / Project No Name 1 1 1 Shyama Club, 22/H/3, Hagen Chatterjee Road, KMC CUDP 2 1 1 WHU-1, 1B, G. C. Road , Kol-2 KMC CUDP Paschim Banga Samaj Seva Samiti ,35/2, B.T. Paschim Banga 3 1 1 NGO Road, Kol-2 Samaj Seba Samiti North Subarban Hospital,82, Cossipur Road, Kol- 4 1 1 DFWB Govt. of W.B. 2 5 2 1 6 PALLY CLUB, 15/B , K.C. Sett Lane, Kol-30 KMUHO Zone-II WHU - 2, 126, K. C. GHOSH ROAD, 6 2 1 KMC CUDP KOL - 50 7 3 1 Friend Circle, 21No. Bustee, Kol - 37 KMC CUDP Belgachia Basti Sudha Committee Club,1/2, J.K. 8 3 1 KMUHO Zone-II Ghosh Road,Lal Maidan, Kol-37 Netaji Sporting Club, 15/H/2/1, Dum Dum Road, 9 4 1 KMUHO Zone-II Kol-30,(Near Mother Diary). 10 4 1 Camelia Building, 26/59, Dum Dum Road, Kol-2, ICDS Belgachia Friends Association Cosmos Club, 89/1 Belgachia 11 5 1 ICDS Belgachia Road.Kol-37 Indira Matri O Shishu Kalyan Hospital, 12 5 1 Govt.Hospital Govt. of W.B. 35/B, Raja Manindra Road, Kol - 37 W.H.U. - 6, 10, B.T. Road, Kol-2 , Paikpara (at 13 6 1 KMC CUDP Borough Cold Chain Point) Gun & Cell Factory Hospital, Kossipur, Kol-2 Gun & Shell 14 6 1 CGO (Ordanance Factory Hospital) Ph # 25572350 Factory Hospital Gangadhar Sporting Club, P-37, Stand Bank 15 6 1 ICDS Bagbazar Road, Kol - 2 Radha Madhab Sporting Club, 8/1, Radha 16 8 1 Madhab Goswami Lane, Kol-3.Near Central KMUHO Zone-II Medical Store, Bagbazar Kumartully Seva Samity, 519A, Rabindra Sarani, Kumartully Seva 17 8 1 NGO kol-3 Samity Nagarik Sammelani,3/D/1, Raja Naba Krishna 18 9 1 KMUHO Zone-II Street, kol-5 Borough-2 1 11 2 160,Arobindu Sarani ,Kol-6 KMC CUDP 2 15 2 Ward Health Unit - 15. -

An Urban River on a Gasping State: Dilemma on Priority of Science, Conscience and Policy

An urban river on a gasping state: Dilemma on priority of science, conscience and policy Manisha Deb Sarkar Former Associate Professor Department of Geography Women’s Christian College University of Calcutta 6, Greek Church Row Kolkata - 700026 SKYLINE OF KOLKATA METROPOLIS KOLKATA: The metropolis ‘Adi Ganga: the urban river • Human settlements next to rivers are the most favoured sites of habitation. • KOLKATA selected to settle on the eastern bank of Hughli River – & •‘ADI GANGA’, a branched out tributary from Hughli River, a tidal river, favoured to flow across the southern part of Kolkata. Kolkata – View from River Hughli 1788 ADI GANGA Present Transport Network System of KOLKATA Adi Ganga: The Physical Environment & Human Activities on it: PAST & PRESNT Adi Ganga oce upo a tie..... (British period) a artists ipressio Charles Doyle (artist) ‘Adi Ganga’- The heritage river at Kalighat - 1860 Width of the river at this point of time Adi Ganga At Kalighat – 1865 source: Bourne & Shepard Photograph of Tolly's Nullah or Adi Ganga near Kalighat from 'Views of Calcutta and Barrackpore' taken by Samuel Bourne in the 1860s. The south-eastern Calcutta suburbs of Alipore and Kalighat were connected by bridges constructed over Tolly's Nullah. Source: British Library ’ADI Ganga’ & Kalighat Temple – an artists ipressio in -1887 PAST Human Activities on it: 1944 • Transport • Trade • Bathing • Daily Domestic Works • Performance of Religious Rituals Present Physical Scenario of Adi Ganga (To discern the extant physical condition and spatial scales) Time Progresses – Adi Ganga Transforms Laws of Physical Science Tidal water flow in the river is responsible for heavy siltation in the river bed. -

Kolkata the Gazette

Registered No. WB/SC-247 No. WB(Part-III)/2021/SAR-9 The Kolkata Gazette Extraordinary Published by Authority SRAVANA 4] MONDAY, JUly 26, 2021 [SAKA 1943 PART III—Acts of the West Bengal Legislature. GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL LAW DEPARTMENT Legislative NOTIFICATION No. 573-L.—26th July, 2021.—The following Act of the West Bengal Legislature, having been assented to by the Governor, is hereby published for general information:— West Bengal Act IX of 2021 THE WEST BENGAL FINANCE ACT, 2021. [Passed by the West Bengal Legislature.] [Assent of the Governor was first published in the Kolkata Gazette, Extraordinary, of the 26th July, 2021.] An Act to amend the Indian Stamp Act, 1899, in its application to West Bengal and the West Bengal Goods and Services Tax Act, 2017. WHEREAS it is expedient to amend the Indian Stamp Act, 1899, in its application to 2 of 1899. West Bengal and the West Bengal Goods and Services Tax Act, 2017, for the purposes West Ben. Act and in the manner hereinafter appearing; XXVIII of 2017. It is hereby enacted in the Seventy-second Year of the Republic of India, by the Legislature of West Bengal, as follows:— Short title and 1. (1) This Act may be called the West Bengal Finance Act, 2021. commencement. (2) Save as otherwise provided, this section shall come into force with immediate effect, and the other provisions of this Act shall come into force on such date, with prospective or retrospective effect as required, as the State Government may, by 2 THE KOLKATA GAZETTE, EXTRAORDINARY, JUly 26, 2021 PART III] The West Bengal Finance Act, 2021. -

Slum Diversity in Kolkata

SLUM DIVERSITY IN KOLKATA SLUM DIVERSITY IN KOLKATA W. COLLIN SCHENK UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA ABSTRACT: Kolkata's slums contain a wealth of diversity that is obscured by the poverty and disorganization surrounding the communities. This paper delineates the categories of slums according to their historical generative forces, details the ethnic composition of slums, and examines the historical patterns of slum policies. Case studies from other researchers are used to paint a picture of slum diversity. The data from the studies is also foundational in the analysis of how historical influences and ethnicity have shaped current conditions in the slums. 91 COLUMBIA UNDERGRADUATE JOURNAL OF SOUTH ASIAN STUDIES Introduction lum-dwellers account for one-third of Kolkata’s total population. This amounts to 1,490,811 people living without adequate basic amenities in over-crowded and S 1 unsanitary settlements. Considering the challenge of counting undocumented squatters and residents of sprawling bastis, this number may be a generous underestimate by the Indian census. The slums’ oftentimes indistinguishable physical boundaries further complicate researchers’ investigations of slums’ diverse physical, social, and economic compositions. In this paper, I will elucidate the qualities of Kolkata’s slums by utilizing past researchers’ admirable efforts to overcome these barriers in studying the slums. The general term slum can refer to both bastis and squatter settlements. Bastis are legally recognized settlements that the Kolkata Municipal Corporation supplies with services such as water, latrines, trash removal, and occasionally electricity. Basti huts typically are permanent structures that the government will not demolish, which allows basti communities to develop a sense of permanency and to focus on issues of poverty beyond shelter availability. -

West Bengal Towards Change

West Bengal Towards Change Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation Research Foundation Published By Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee Research Foundation 9, Ashoka Road, New Delhi- 110001 Web :- www.spmrf.org, E-Mail: [email protected], Phone:011-23005850 Index 1. West Bengal: Towards Change 5 2. Implications of change in West Bengal 10 politics 3. BJP’s Strategy 12 4. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s 14 Statements on West Bengal – excerpts 5. Statements of BJP National President 15 Amit Shah on West Bengal - excerpts 6. Corrupt Mamata Government 17 7. Anti-people Mamata government 28 8. Dictatorship of the Trinamool Congress 36 & Muzzling Dissent 9. Political Violence and Murder in West 40 Bengal 10. Trinamool Congress’s Undignified 49 Politics 11. Politics of Appeasement 52 12. Mamata Banerjee’s attack on India’s 59 federal structure 13. Benefits to West Bengal from Central 63 Government Schemes 14. West Bengal on the path of change 67 15. Select References 70 West Bengal: Towards Change West Bengal: Towards Change t is ironic that Bengal which was once one of the leading provinces of the country, radiating energy through its spiritual and cultural consciousness across India, is suffering today, caught in the grip Iof a vicious cycle of the politics of violence, appeasement and bad governance. Under Mamata Banerjee’s regime, unrest and distrust defines and dominates the atmosphere in the state. There is a no sphere, be it political, social or religious which is today free from violence and instability. It is well known that from this very land of Bengal, Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore had given the message of peace and unity to the whole world by establishing Visva Bharati at Santiniketan. -

Kolkata Police Notification to House Owners

Kolkata Police notification to House Owners The Commissioner of Police, Kolkata and Executive Magistrate has ordered u/s 144 of CrPC, 1973, that no landlord/owner/person whose house property falls under the jurisdiction of the area of Police Station specified in the Schedule–I appended below shall let/sublet/rent out any accommodation to any persons unless and untill he/she has furnished the particulars of the said tenants as per proforma in Schedule–II appended below to the Officer–in-Charge of the Police Station concerned. All persons who intend to take accommodation on rent shall inform in writing in this regard to the Officer-in–Charge of the Police Station concerned in whose jurisdiction the premises fall. The persons dealing in property business shall also inform in writing to the Officer-in-Charge of the Police Station concerned in whose jurisdiction the premises fall about the particulars of the tenants. This order has come into force from 9.7.2012 and shall be effective for a period of 60 days i.e. upto 6.9.2012 unless withdrawn earlier. Schedule-I Divisionwise PS List Sl. Sl. No. North Division E.S.D Sl. No. Central Division No. 1. Shyampukur PS 1. Manicktala PS 1. Burrabazar PS 2. Jorabagan PS 2. Ultadanga PS 2. Posta PS 3. Burtala PS 3. Entally PS 3. Jorasanko PS 4. Amherst St. PS 4. Phoolbagan PS 4. Hare Street PS 5. Cossipore PS 5. Narkeldanga PS 5. Bowbazar PS 6. Chitpur PS 6. Beniapukur PS 6. Muchipara PS 7. Sinthee PS 7. -

Inner-City and Outer-City Neighbourhoods in Kolkata: Their Changing Dynamics Post Liberalization

Article Environment and Urbanization ASIA Inner-city and Outer-city 6(2) 139–153 © 2015 National Institute Neighbourhoods in Kolkata: of Urban Affairs (NIUA) SAGE Publications Their Changing Dynamics sagepub.in/home.nav DOI: 10.1177/0975425315589157 Post Liberalization http://eua.sagepub.com Annapurna Shaw1 Abstract The central areas of the largest metropolitan cities in India are slowing down. Outer suburbs continue to grow but the inner city consisting of the oldest wards is stagnating and even losing population. This trend needs to be studied carefully as its implications are deep and far-reaching. The objective of this article is to focus on what is happening to the internal structure of the city post liberalization by highlighting the changing dynamics of inner-city and outer-city neighbourhoods in Kolkata. The second section provides a brief background to the metropolitan region of Kolkata and the city’s role within this region. Based on ward-level census data for the last 20 years, broad demographic changes under- gone by the city of Kolkata are examined in the third section. The drivers of growth and decline and their implications for livability are discussed in the fourth section. In the fifth section, field observations based on a few representative wards are presented. The sixth section concludes the article with policy recommendations. 加尔各答内城和外城社区:后自由主义化背景下的动态变化 印度最大都市区中心地区的发展正在放缓。远郊持续增长,但拥有最老城区的内城停滞不 前,甚至出现人口外流。这种趋势需要仔细研究,因为它的影响是深刻而长远的。本文的目 的是,通过强调加尔各答内城和外城社区的动态变化,关注正在发生的后自由化背景下的城 市内部结构。第二部分提供了概括性的背景,介绍了加尔各答的大都市区,以及城市在这个 区域内的角色。在第三部分中,基于过去二十年城区层面的人口普查数据,研究考察了加尔 各答城市经历的广泛的人口变化。第四部分探讨了人口增长和衰退的推动力,以及它们对于 城市活力的影响。第五部分展示了基于几个有代表性城区的实地观察。第六部分提出了结论 与政策建议。 Keywords Inner city, outer city, growth, decline, neighbourhoods 1 Professor, Public Policy and Management Group, Indian Institute of Management Calcutta, Kolkata, India.