Full Text: DOI

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POSTCOLONIAL WRITINGS- II Semester

POSTCOLONIAL WRITINGS [ENG2C08] STUDY MATERIAL II SEMESTER CORE COURSE MA ENGLISH (2019 Admission onwards) UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION CALICUT UNIVERSITY- P.O MALAPPURAM- 673635, KERALA 190008 ENG2C08-POSTCOLONIAL WRITINGS SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT STUDY MATERIAL SECOND SEMESTER MA ENGLISH (2019 ADMISSION ONWARDS) CORE COURSE: ENG2C08 : POSTCOLONIAL WRITINGS Prepared by: SMT. SABINA K MUSTHAFA Assistant Professor on Contract Department of English University of Calicut Scrutinized by: Dr. K.M.SHERRIF Associate Professor & Head Department of English University of Calicut ENG2C08-POSTCOLONIAL WRITINGS CONTENTS SECTION A: POETRY 1. A K RAMANUJAN: “SELF-PORTRAIT” 2. DOM MORAES: “A LETTER” “SINBAD” 3. LEOPOLD SENGHOR: “NEW YORK” 4. GABRIEL OKARA: “THE MYSTIC DRUM” 5. DAVID DIOP: “AFRICA” 6. ALLEN CURNOW: “HOUSE AND LAND” 7. A D HOPE: “AUSTRALIA” 8. JACK DAVIS: “ABORIGINAL AUSTRALIA” 9. MARGARET ATWOOD: “JOURNEY TO THE INTERIOR” 10. DEREK WALCOTT: “RUINS OF A GREAT HOUSE” 11. EE TIANG HONG: “ARRIVAL” 12. ALMAGHIR HASHMI: “SO WHAT IF I LIVE IN A HOUSE MADE BY IDIOTS?” 13. KAMAU BRATHWAITE: “NEGUS” SECTION B 1. WOLE SOYINKA: THE ROAD 2. GIRISH KARNAD: HAYAVADANA 3. TIMBERLAKE WERTENBAKER: OUR COUNTRY’S GOOD SECTION C 1. CHINUA ACHEBE: THINGS FALL APART 2. V. S NAIPAUL: A HOUSE FOR MR. BISWAS 3. MARGARET LAWRENCE: THE STONE ANGEL 4. KHALED HOSSEINI: THE KITE RUNNER INTRODUCTION POSTCOLONIALISM We encounter a remarkably wide range of literary texts that come from parts of the world as varied as India, West Indies, Africa, Canada, Australia and South America against the backdrop of colonialism and resistance to colonialism, cultural legacies of colonialism as well as those who want to actively engage with the process of decolonization or think through the process of decolonization. -

Bengali Association of Greater Rochester (BAGR) Presents Its Annual Bijoya Celebrations Which Comprise of Equally Enthralling Programs

Bengali Association of Greater Rochester September 30th2016 2015 Bengali association of greater Rochester www.bagrusa.org ♦ [email protected] On sixth day of Navratri, we get new touch, on seventh filled with mist in air, on Executive Committee eighth we offer flowers, on ninth day we have fun, and on tenth day, we enjoy sweets. 2016-2017 Hope Durga Puja is fun-filled for all. Anindita Biswas President Elo Sharad, Somoy Sharodotsab Er Email: [email protected] Over the last year, there has been a lot going on in our personal lives, our Krishna Chakraborty communities and throughout the world. Whether it is the economic crisis, Secretary Email: [email protected] political issues or natural calamities all over the world, we all have a lot of Shusanta Choudhury worries occupying our minds and hearts. But with the advent of autumn or fall Treasurer all those thoughts, worries are pushed to the back of our mind and a strange Email: [email protected] nostalgic feeling grips our hearts. It takes us back to the bylanes of our Anusri Sarkar hometowns back in India and brings up memories of crowded bazaar with Member people frantically finishing last minute Puja shopping. At the same time Uttara Bhattacharya neighborhood clubs collecting chanda (donation) for Puja and folks setting up Member bamboo scaffoldings desperately trying to finish pandal set up which Nandita Maity ultimately will resemble the White House or Victoria Memorial. Member Durga Puja, the most widely celebrated festival of the Bengalis can be enjoyed Padmini Das by its spurt of fanfare on all the four days of the Durga Puja festival visible Member throughout India, and particularly in Bengal. -

Lions Clubs International

Lions Clubs International Clubs Missing a Current Year Club Officer (Only President, Secretary or Treasurer) as of July 08, 2010 District 322 B2 Club Club Name Title (Missing) 34589 SHYAMNAGAR President 34589 SHYAMNAGAR Secretary 34589 SHYAMNAGAR Treasurer 42234 KANCHRAPARA President 42234 KANCHRAPARA Secretary 42234 KANCHRAPARA Treasurer 46256 CALCUTTA WOODLANDS President 46256 CALCUTTA WOODLANDS Secretary 46256 CALCUTTA WOODLANDS Treasurer 61410 CALCUTTA EAST WEST President 61410 CALCUTTA EAST WEST Secretary 61410 CALCUTTA EAST WEST Treasurer 63042 BASIRHAT President 63042 BASIRHAT Secretary 63042 BASIRHAT Treasurer 66648 AURANGABAD GREATER Secretary 66648 AURANGABAD GREATER Treasurer 66754 BERHAMPORE BHAGIRATHI President 66754 BERHAMPORE BHAGIRATHI Secretary 66754 BERHAMPORE BHAGIRATHI Treasurer 84993 CALCUTTA SHAKESPEARE SARANI President 84993 CALCUTTA SHAKESPEARE SARANI Secretary 84993 CALCUTTA SHAKESPEARE SARANI Treasurer 100797 KOLKATA INDIA EXCHANGE GREATER President 100797 KOLKATA INDIA EXCHANGE GREATER Secretary 100797 KOLKATA INDIA EXCHANGE GREATER Treasurer 101372 DUM DUM GREATER President 101372 DUM DUM GREATER Secretary 101372 DUM DUM GREATER Treasurer 102087 BARASAT CITY President 102087 BARASAT CITY Secretary 102087 BARASAT CITY Treasurer 102089 KOLKATA VIP PURWANCHAL President OFF0021 Run Date: 7/8/2010 11:44:11AM Page 1 of 2 Lions Clubs International Clubs Missing a Current Year Club Officer (Only President, Secretary or Treasurer) as of July 08, 2010 District 322 B2 Club Club Name Title (Missing) 102089 KOLKATA VIP -

Numbers in Bengali Language

NUMBERS IN BENGALI LANGUAGE A dissertation submitted to Assam University, Silchar in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts in Department of Linguistics. Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGE ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR 788011, INDIA YEAR OF SUBMISSION : 2020 CONTENTS Title Page no. Certificate 1 Declaration by the candidate 2 Acknowledgement 3 Chapter 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1.0 A rapid sketch on Assam 4 1.2.0 Etymology of “Assam” 4 Geographical Location 4-5 State symbols 5 Bengali language and scripts 5-6 Religion 6-9 Culture 9 Festival 9 Food havits 10 Dresses and Ornaments 10-12 Music and Instruments 12-14 Chapter 2: REVIEW OF LITERATURE 15-16 Chapter 3: OBJECTIVES AND METHODOLOGY Objectives 16 Methodology and Sources of Data 16 Chapter 4: NUMBERS 18-20 Chapter 5: CONCLUSION 21 BIBLIOGRAPHY 22 CERTIFICATE DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGES ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR DATE: 15-05-2020 Certified that the dissertation/project entitled “Numbers in Bengali Language” submitted by Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 of 2018-2019 for Master degree in Linguistics in Assam University, Silchar. It is further certified that the candidate has complied with all the formalities as per the requirements of Assam University . I recommend that the dissertation may be placed before examiners for consideration of award of the degree of this university. 5.10.2020 (Asst. Professor Paramita Purkait) Name & Signature of the Supervisor Department of Linguistics Assam University, Silchar 1 DECLARATION I hereby Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No – 03-120032252 hereby declare that the subject matter of the dissertation entitled ‘Numbers in Bengali language’ is the record of the work done by me. -

Metro Railway Kolkata Presentation for Advisory Board of Metro Railways on 29.6.2012

METRO RAILWAY KOLKATA PRESENTATION FOR ADVISORY BOARD OF METRO RAILWAYS ON 29.6.2012 J.K. Verma Chief Engineer 8/1/2012 1 Initial Survey for MTP by French Metro in 1949. Dum Dum – Tollygunge RTS project sanctioned in June, 1972. Foundation stone laid by Smt. Indira Gandhi, the then Prime Minister of India on December 29, 1972. First train rolled out from Esplanade to Bhawanipur (4 km) on 24th October, 1984. Total corridor under operation: 25.1 km Total extension projects under execution: 89 km. June 29, 2012 2 June 29, 2012 3 SEORAPFULI BARRACKPUR 12.5KM SHRIRAMPUR Metro Projects In Kolkata BARRACKPUR TITAGARH TITAGARH 10.0KM BARASAT KHARDAH (UP 17.88Km) KHARDAH 8.0KM (DN 18.13Km) RISHRA NOAPARA- BARASAT VIA HRIDAYPUR PANIHATI AIRPORT (UP 15.80Km) (DN 16.05Km)BARASAT 6.0KM SODEPUR PROP. NOAPARA- BARASAT KONNAGAR METROMADHYAMGRAM EXTN. AGARPARA (UP 13.35Km) GOBRA 4.5KM (DN 13.60Km) NEW BARRACKPUR HIND MOTOR AGARPARA KAMARHATI BISARPARA NEW BARRACKPUR (UP 10.75Km) 2.5KM (DN 11.00Km) DANKUNI UTTARPARA BARANAGAR BIRATI (UP 7.75Km) PROP.BARANAGAR-BARRACKPORE (DN 8.00Km) BELGHARIA BARRACKPORE/ BELA NAGAR BIRATI DAKSHINESWAR (2.0Km EX.BARANAGAR) BALLY BARANAGAR (0.0Km)(5.2Km EX.DUM DUM) SHANTI NAGAR BIMAN BANDAR 4.55KM (UP 6.15Km) BALLY GHAT RAMKRISHNA PALLI (DN 6.4Km) RAJCHANDRAPUR DAKSHINESWAR 2.5KM DAKSHINESWAR BARANAGAR RD. NOAPARA DAKSHINESWAR - DURGA NAGAR AIRPORT BALLY HALT NOAPARA (0.0Km) (2.09Km EX.DMI) HALDIRAM BARANAGAR BELUR JESSOR RD DUM DUM 5.0KM DUM DUM CANT. CANT 2.60KM NEW TOWN DUM DUM LILUAH KAVI SUBHAS- DUMDUM DUM DUM ROAD CONVENTION CENTER DUM DUM DUM DUM - BELGACHIA KOLKATA DASNAGAR TIKIAPARA AIRPORT BARANAGAR HOWRAH SHYAM BAZAR RAJARHAT RAMRAJATALA SHOBHABAZAR Maidan BIDHAN NAGAR RD. -

Name and Addresses of Routine Immunization Centers in KMC Area

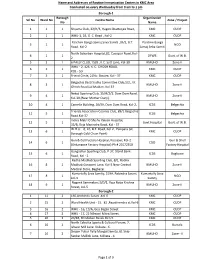

Name and Addresses of Routine Immunization Centers in KMC Area Conducted on every Wednesday from 9 am to 1 pm Borough-1 Borough Organization Srl No Ward No Centre Name Zone / Project No Name 1 1 1 Shyama Club, 22/H/3, Hagen Chatterjee Road, KMC CUDP 2 1 1 WHU-1, 1B, G. C. Road , Kol-2 KMC CUDP Paschim Banga Samaj Seva Samiti ,35/2, B.T. Paschim Banga 3 1 1 NGO Road, Kol-2 Samaj Seba Samiti North Subarban Hospital,82, Cossipur Road, Kol- 4 1 1 DFWB Govt. of W.B. 2 5 2 1 6 PALLY CLUB, 15/B , K.C. Sett Lane, Kol-30 KMUHO Zone-II WHU - 2, 126, K. C. GHOSH ROAD, 6 2 1 KMC CUDP KOL - 50 7 3 1 Friend Circle, 21No. Bustee, Kol - 37 KMC CUDP Belgachia Basti Sudha Committee Club,1/2, J.K. 8 3 1 KMUHO Zone-II Ghosh Road,Lal Maidan, Kol-37 Netaji Sporting Club, 15/H/2/1, Dum Dum Road, 9 4 1 KMUHO Zone-II Kol-30,(Near Mother Diary). 10 4 1 Camelia Building, 26/59, Dum Dum Road, Kol-2, ICDS Belgachia Friends Association Cosmos Club, 89/1 Belgachia 11 5 1 ICDS Belgachia Road.Kol-37 Indira Matri O Shishu Kalyan Hospital, 12 5 1 Govt.Hospital Govt. of W.B. 35/B, Raja Manindra Road, Kol - 37 W.H.U. - 6, 10, B.T. Road, Kol-2 , Paikpara (at 13 6 1 KMC CUDP Borough Cold Chain Point) Gun & Cell Factory Hospital, Kossipur, Kol-2 Gun & Shell 14 6 1 CGO (Ordanance Factory Hospital) Ph # 25572350 Factory Hospital Gangadhar Sporting Club, P-37, Stand Bank 15 6 1 ICDS Bagbazar Road, Kol - 2 Radha Madhab Sporting Club, 8/1, Radha 16 8 1 Madhab Goswami Lane, Kol-3.Near Central KMUHO Zone-II Medical Store, Bagbazar Kumartully Seva Samity, 519A, Rabindra Sarani, Kumartully Seva 17 8 1 NGO kol-3 Samity Nagarik Sammelani,3/D/1, Raja Naba Krishna 18 9 1 KMUHO Zone-II Street, kol-5 Borough-2 1 11 2 160,Arobindu Sarani ,Kol-6 KMC CUDP 2 15 2 Ward Health Unit - 15. -

BHAKTI Temple Hours Mon to Fri: 9 AM – 12:30 PM & 4 PM – 8:30 PM January 2011

Greater Cleveland Shiva Vishnu Temple A Non-profit 7733 Ridge Road Organization P.O. Box 29508 US POSTAGE Parma, OH 44129 PAID Cleveland, OH Permit No. 03879 Phone (440) 888-9433 www.shivavishnutemple.org A Non-Profit Tax-Exempt Organization REGULAR WEEKLY & MONTHLY PUJA SCHEDULE Sunday 9:30 AM Shiva Abhishekam; 11 AM Vishnu Puja st rd 1 Sunday 12:30 PM Jagannath Puja 3 Sunday 12:30 PM Jain Puja Monday 10 AM Shiva Abhishekam; 6 PM Jagannath Puja Tuesday 10 AM Ganesha Abhishekam; 6 PM Hanumanji Puja Wednesday 10 AM Ram Parivar Puja 6 PM Aiyappa Puja; Thursday 10 AM Radha Krishna Puja; 6 PM Shrinathji Puja: Friday 10 AM Parvati Puja (Abhishekam 1st Fri 7:15 p) 6 PM Lakshmi Puja: 6:30 PM Durga Puja 7:15 PM Abhishekam for Sridevi 2nd Fri for Bhudevi 3rd Friday (7:15 p) Saturday 11 AM Vishnu Abhishekam 10 AM Aiyappa Puja 1st Sat 5 PM Karthikeya Puja 6 PM Saraswati Puja; 6:30 PM Navagraha Abhishek 11 AM Venkateswara Abhishekam 2nd & 4th Sat Puja 1st &3rd Sat NITYA PUJA (Monday – Saturday ) 10 AM Shiva Abhishekam; 10 AM Vishnu Puja Highlights of Feb 2011 events Date Day Time Description Feb 2 Wed Amavasya Feb 5 Sat 10 a Sri Aiyappa Puja Feb 7 Mon 10 a Vasant PanchamiSri Saraswati Puja Feb 8 Tue 6 p Sukla Shashthi, Murugabhishekam Feb 17 Wed 7.15 p Pournima, Satyanarayanpuja Feb 20 Sat 6 p Sankatahara Chaturthi,Ganeshabhishekam Mar 2 Wed 6 p Mahashivaratri Visitors are requested to wear appropriate attire in the Temple premises 10pm Mini Aarati Bhajan,Prasad Greater Cleveland Shiva Vishnu Temple BHAKTI Temple Hours Mon to Fri: 9 AM – 12:30 PM -

Durga Pujas of Contemporary Kolkata∗

Modern Asian Studies: page 1 of 39 C Cambridge University Press 2017 doi:10.1017/S0026749X16000913 REVIEW ARTICLE Goddess in the City: Durga pujas of contemporary Kolkata∗ MANAS RAY Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta, India Email: [email protected] Tapati Guha-Thakurta, In the Name of the Goddess: The Durga Pujas of Contemporary Kolkata (Primus Books, Delhi, 2015). The goddess can be recognized by her step. Virgil, The Aeneid,I,405. Introduction Durga puja, or the worship of goddess Durga, is the single most important festival in Bengal’s rich and diverse religious calendar. It is not just that her temples are strewn all over this part of the world. In fact, goddess Kali, with whom she shares a complementary history, is easily more popular in this regard. But as a one-off festivity, Durga puja outstrips anything that happens in Bengali life in terms of pomp, glamour, and popularity. And with huge diasporic populations spread across the world, she is now also a squarely international phenomenon, with her puja being celebrated wherever there are even a score or so of Hindu Bengali families in one place. This is one Bengali festival that has people participating across religions and languages. In that ∗ Acknowledgements: Apart from the two anonymous reviewers who made meticulous suggestions, I would like to thank the following: Sandhya Devesan Nambiar, Richa Gupta, Piya Srinivasan, Kamalika Mukherjee, Ian Hunter, John Frow, Peter Fitzpatrick, Sumanta Banjerjee, Uday Kumar, Regina Ganter, and Sharmila Ray. Thanks are also due to Friso Maecker, director, and Sharmistha Sarkar, programme officer, of the Goethe Institute/Max Mueller Bhavan, Kolkata, for arranging a conversation on the book between Tapati Guha-Thakurta and myself in September 2015. -

ZEEMEDIA [email protected]

ZEEMEDIA [email protected] Collaborative Strategies C o h e s i v e G r o w t h ZEEMEDIA ZEE MEDIA CORPORATION LIMITED REGISTERED OFFICE 14th Floor, A Wing, Marathon Futurex, NM Joshi Marg, Lower Parel, Mumbai - 400013 Maharashtra Tel.: +91 22 7106 1234 Fax: +91 22 2300 2107 Website: www.zeenews.india.com Annual Report 2017-18 OUR ZEEMEDIA PRESENCE INSIDE THIS REPORT Corporate Overview Collaborative Strategies Cohesive Growth 01 Growing Together with Viewer Engagement 02 Growing Together with Advertisers' Reach 03 Growing Together with Society and Government 04 Growing Together with Our Employees - Our Trusted Aides 05 Srinagar Steadfast Progress, Nurturing New Ventures 06 Jammu Raising the Bar with Innovations 08 Message to Shareholders 10 Growth Firmly Embedded in Value System 12 Chandigarh Dehradun Our Channels and Digital Platforms 13 Corporate Information 16 Noida STATUTORY REPORTS Lucknow Varanasi Notice 17 Jaipur Ajmer Directors' Report 26 Patna Corporate Governance Report 43 Kota Management Discussion and Analysis 56 Ranchi Kolkata Ahmedabad Bhopal Indore Vadodara FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Rajkot Raipur Surat Standalone Financial Statements 67 Nagpur Consolidated Financial Statements 121 Bhubaneswar Nasik Aurangabad Thane Mumbai BSE, Mumbai Pune Kohlapur Hyderabad FORWARD LOOKING STATEMENTS Bengaluru Certain statements in this annual report concerning our future growth prospects are forward-looking statements, which involve a number of risks and uncertainties that could cause actual results to differ materially from those in such forward-looking statements. We have tried wherever possible to identify such statements by using words such as 'anticipate', 'estimate', 'expect', 'project', 'intend', 'plan', 'believe' and words of similar substance in connection with any discussion of future performance. -

Kolkata the Gazette

Registered No. WB/SC-247 No. WB(Part-III)/2021/SAR-9 The Kolkata Gazette Extraordinary Published by Authority SRAVANA 4] MONDAY, JUly 26, 2021 [SAKA 1943 PART III—Acts of the West Bengal Legislature. GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL LAW DEPARTMENT Legislative NOTIFICATION No. 573-L.—26th July, 2021.—The following Act of the West Bengal Legislature, having been assented to by the Governor, is hereby published for general information:— West Bengal Act IX of 2021 THE WEST BENGAL FINANCE ACT, 2021. [Passed by the West Bengal Legislature.] [Assent of the Governor was first published in the Kolkata Gazette, Extraordinary, of the 26th July, 2021.] An Act to amend the Indian Stamp Act, 1899, in its application to West Bengal and the West Bengal Goods and Services Tax Act, 2017. WHEREAS it is expedient to amend the Indian Stamp Act, 1899, in its application to 2 of 1899. West Bengal and the West Bengal Goods and Services Tax Act, 2017, for the purposes West Ben. Act and in the manner hereinafter appearing; XXVIII of 2017. It is hereby enacted in the Seventy-second Year of the Republic of India, by the Legislature of West Bengal, as follows:— Short title and 1. (1) This Act may be called the West Bengal Finance Act, 2021. commencement. (2) Save as otherwise provided, this section shall come into force with immediate effect, and the other provisions of this Act shall come into force on such date, with prospective or retrospective effect as required, as the State Government may, by 2 THE KOLKATA GAZETTE, EXTRAORDINARY, JUly 26, 2021 PART III] The West Bengal Finance Act, 2021. -

Nissim Ezekiel's Literary Skill in Depicting Indian

Research Paper Peer Reviewed Monthly Journal AIJRRR Impact Factor: 5.002 ISSN :2456-205X NISSIM EZEKIEL’S LITERARY SKILL IN DEPICTING INDIAN SENSIBILITY AND SOCIAL REALITY WITH A HUMANISTIC STRAIN IN HIS POETRY: AN APPRAISAL Dr. S. Chelliah Professor, Head and Chairperson, School of English & Foreign Languages, Department of English & Comparative Literature, Madurai Kamaraj University, Madurai. Abstract This paper attempts to describe Nissim Ezekiel as the pioneer of “New Poetry” by his greater variety and depth than any other poet of the post-independence period and shows how Ezekiel brought a sense of discipline, self-criticism and mastery to Indian English Poetry through use of simplicity of thought and lucid language style in modern poetry. No doubt, the Indian element in Ezekiel’s poetry derives its strength from his choice of themes and allusions and his poetry does pasteurized the social aspects of Indian with a humanistic strain raising a bitter voice against the thoughts of injustice and inequality. Finally, it attests to the common fact that Ezekiel had been encouraging the Indian sensibility and Indian context through his poetic outpourings in verse forms. Key Words: Indian Sensibility, Humanity, Introspection, Realistic Experiences, in justice. Indian English poetry is generally found to be remarkable for profound experimentation and vivid presentation of contemporary reality. The so-called political situation due to the partition of the country assassination of the Mahatma, the rapid urbanization and sound industrialization of the nation, the total disintegration of village community, the essential problem of cultural identity and the swift changes in cultural and societal values and issues did significantly compel the attention of the new poets all and sundry. -

Blurring Boundaries: the Limits of "White Town" in Colonial Calcutta Author(S): Swati Chattopadhyay Source: Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol

Blurring Boundaries: The Limits of "White Town" in Colonial Calcutta Author(s): Swati Chattopadhyay Source: Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 59, No. 2 (Jun., 2000), pp. 154-179 Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the Society of Architectural Historians Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/991588 Accessed: 19-09-2016 20:16 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Society of Architectural Historians, University of California Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians This content downloaded from 128.59.129.95 on Mon, 19 Sep 2016 20:16:50 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Blurring Boundaries The Limits of "White Town" in Colonial Calcutta SWATI CHATTOPADHYAY University of California, Santa Barbara O ne of the enduring assumptions about colonial culture penetrated the insularity of both towns, although at cities of the modern era is that they worked on the different levels and to varying degrees. As an examination of basis of separation-they were "dual cities" the