Blurring Boundaries: the Limits of "White Town" in Colonial Calcutta Author(S): Swati Chattopadhyay Source: Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (2216Kb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/150023 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications ‘AN ENDLESS VARIETY OF FORMS AND PROPORTIONS’: INDIAN INFLUENCE ON BRITISH GARDENS AND GARDEN BUILDINGS, c.1760-c.1865 Two Volumes: Volume I Text Diane Evelyn Trenchard James A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Warwick, Department of History of Art September, 2019 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ………………………………………………………………. iv Abstract …………………………………………………………………………… vi Abbreviations ……………………………………………………………………. viii . Glossary of Indian Terms ……………………………………………………....... ix List of Illustrations ……………………………………………………………... xvii Introduction ……………………………………………………………………….. 1 1. Chapter 1: Country Estates and the Politics of the Nabob ………................ 30 Case Study 1: The Indian and British Mansions and Experimental Gardens of Warren Hastings, Governor-General of Bengal …………………………………… 48 Case Study 2: Innovations and improvements established by Sir Hector Munro, Royal, Bengal, and Madras Armies, on the Novar Estate, Inverness, Scotland …… 74 Case Study 3: Sir William Paxton’s Garden Houses in Calcutta, and his Pleasure Garden at Middleton Hall, Llanarthne, South Wales ……………………………… 91 2. Chapter 2: The Indian Experience: Engagement with Indian Art and Religion ……………………………………………………………………….. 117 Case Study 4: A Fairy Palace in Devon: Redcliffe Towers built by Colonel Robert Smith, Bengal Engineers ……………………………………………………..…. -

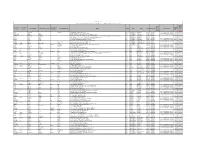

List of Shareholders' Unclaimed Dividend Amount For

Control Print Limited DETAILED OF SHAREHOLDERS UNPAID/UNCLAIMED DIVIDEND AMT. FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR 2013-2014 AS ON 15/09/2017 Proposed DP Id- Date of Amount Investor First Investor Middle Father/Husband Client Id- transfer to Investor Last Name Father/Husband First Name Father/Husband Last Name Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transferr Name Name Middle Name Account IEPF ed Number (DD-MON- YYYY) VIKAS B PARANJAPE B PARANJAPE 18-B LOKMANYA NAGAR MAHIM MUMBAI INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI CITY 400016 FOLIO000010 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend250.00 19-OCT-2021 SIDDHARTHA SINGH SINGH FLAT NO 9 DEVI SHELTER PLOT NO 108 VIMAN NAGAR INDIA MAHARASHTRA PUNE 411014 FOLIO000025 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend2000.00 19-OCT-2021 VISHWANATH AREKAR AREKAR METAGRAPHS PVT LTD 164 SENAPATHI BAPAT MARG MATUNGA MUMBAI INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI CITY 400019 FOLIO000029 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend1500.00 19-OCT-2021 MOHYNA SRINIVASAN SRINIVASAN C/O MS. LORRAINE D'SOUZA PRUDENTIAL ICICI AMC LTD. CONTRACTOR BLDG., 3RD FLOOR 41 R KAMANI MARG, BALLARD ESTATE, MUMBAI INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI CITY 400038 FOLIO000031 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend500.00 19-OCT-2021 RITA SINGH SINGH 9/8/43 NAVJIVAN HSG CO OP HSG SOCY LAMINGTON ROAD MUMBAI CENTRAL MUMBAI INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI CITY 400008 FOLIO000061 Amount for unclaimed and unpaid dividend1875.00 19-OCT-2021 SUDHIR PATEL PATEL CHOWPATI VIEW BLOCK-9, 2ND FLOOR MORVI LANE, CHOWPATI MUMBAI INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI CITY 400007 FOLIO000078 Amount -

Top 50 Exporters During 2018-19

Top 50 Exporters during 2018-19 Sl. Name Head Office Contact No. S.S.K.Exports 37, Shakespeare Sarani, Kolkata, 033 2230 1574 1 Limited. West Bengal, PIN- 700017 [email protected] 4, Mangoe Lane, Near Surendra Mohan Mcleod Russel 033 2210 1221 2 Ghosh Sarani, Kolkata, West Bengal, India Limited [email protected] PIN- 700069 Girnar Food & Girnar Complex, Kureshi Nagar,Kurla East, 022 4343 7000 / 022 2405 6403 3 Beverages Pvt. Ltd. Mumbai, Maharashtra, PIN- 400070 [email protected] 1, Manook Lane, 1st Floor, SHAH HOUSE, 033 2234 2893 4 Shah Brothers Kolkata, West Bengal, PIN- 700001 [email protected] 54, Ezra Street, Kolkata, 033 2235 3678 5 Bhansali & Co. West Bengal, PIN-700001 [email protected] Vikrma Impex (P) 32,Jawaharlal Nehru Road ,11th Floor, 033 2226 6103 / 5728 6 Ltd. Kolkata, West Bengal, PIN-700071 [email protected] 4/1, Middleton Street ,5th Floor, Sikkim Asian Tea Company 033 4044 1201/02 7 Commerce House, Kolkata, West Bengal, Private Limited [email protected] PIN-700071 A.Tosh & Sons Tosh House ,P-32 & 33, India Exchange 033 3028 9651 8 (India)Ltd. Place, Kolkata, West Bengal PIN-700001 [email protected] 32, Jawaharlal Nehru Road, ,11th Floor, 033 2226 6103 / 5726 9 Balaji Agro Pvt.Ltd., Kolkata, West Bengal, PIN-700071 [email protected] Madhu Jayanti Jay Complex , 46, B.B.Ganguly Street, 033 2225 7422 10 International Ltd. Kolkata ,West Bengal , PIN-700012 [email protected] Kasturi Building, 2nd Floor, 171/172, J.V.Gokal & Co. Pvt. 0484 2413347 11 Jamshedji Tata Road, Maharashtra, Ltd. -

India-Ahmedabad-Retail Q3 2019

KOLKATA RETAIL SEPTEMBER 2019 MARKETBEAT 5.97% 4-8% 0.58 msf MALL VACANCY Q - O - Q RENT GROWTH -S E L E C T UPCOMING MALL ( Q 3 2 0 1 9 ) MAIN STREETS & SUBMARKETS SUPPLY (Q4 2019 - 2020) HIGHLIGHTS ECONOMIC INDICATORS 2019 Low vacancy impacting traction in malls 2017 2018 Forecast Mall vacancy recorded a marginal decline q-o-q to 5.97%, with prime malls already running at high GDP Growth 7.2% 6.8% 6.1% occupancies. This resulted in an increased retailer traction on main streets during the quarter. So, CPI Growth 3.6% 3.5% 3.4% while prominent main streets like Park Street, Chowringhee Road and Hatibagan contributed Consumer spending 7.4% 8.1% 5.5% extensively to the leasing activity in Q3, few retailers were also keen to explore spaces vacated by Govt. Final other brands in prominent malls like South City and Quest. Negligible mall supply getting added Expenditure Growth 14.2% 9.2% 6.0% over the last few quarters and very low upcoming supply by 2020, is also likely to affect traction in Source: Oxford Economics, RBI, Central Statistics Office malls in the coming quarters, except a retailer churn, while prominent main streets are expected to perform well. MALL SUPPLY / VACANCY 700 7% Fashion and F&B segments driving demand 600 6% 500 5% Fashion, apparel and accessories followed by F&B continue to remain the most active retail 4% 400 segments in terms of space take-up with brands like Zudio, L’Occitane, Nykaa, VIP, Burger King, 3% 300 2% and Taco Bell among others taking up space this quarter. -

Download Book

"We do not to aspire be historians, we simply profess to our readers lay before some curious reminiscences illustrating the manners and customs of the people (both Britons and Indians) during the rule of the East India Company." @h£ iooi #ld Jap €f Being Curious Reminiscences During the Rule of the East India Company From 1600 to 1858 Compiled from newspapers and other publications By W. H. CAREY QUINS BOOK COMPANY 62A, Ahiritola Street, Calcutta-5 First Published : 1882 : 1964 New Quins abridged edition Copyright Reserved Edited by AmARENDRA NaTH MOOKERJI 113^tvS4 Price - Rs. 15.00 . 25=^. DISTRIBUTORS DAS GUPTA & CO. PRIVATE LTD. 54-3, College Street, Calcutta-12. Published by Sri A. K. Dey for Quins Book Co., 62A, Ahiritola at Express Street, Calcutta-5 and Printed by Sri J. N. Dey the Printers Private Ltd., 20-A, Gour Laha Street, Calcutta-6. /n Memory of The Departed Jawans PREFACE The contents of the following pages are the result of files of old researches of sexeral years, through newspapers and hundreds of volumes of scarce works on India. Some of the authorities we have acknowledged in the progress of to we have been indebted for in- the work ; others, which to such as formation we shall here enumerate ; apologizing : — we may have unintentionally omitted Selections from the Calcutta Gazettes ; Calcutta Review ; Travels Selec- Orlich's Jacquemont's ; Mackintosh's ; Long's other Calcutta ; tions ; Calcutta Gazettes and papers Kaye's Malleson's Civil Administration ; Wheeler's Early Records ; Recreations; East India United Service Journal; Asiatic Lewis's Researches and Asiatic Journal ; Knight's Calcutta; India. -

A Study on the Colonial Monuments of British Era of Kolkata, India Mesaria S

Research Journal of Recent Sciences _________________________________________________ ISSN 2277-2502 Vol. 3(IVC-2014), 99-107 (2014) Res. J. Recent. Sci. A Study on the Colonial Monuments of British Era of Kolkata, India Mesaria S. 1 and Jaiswal N. 2 Department of Family and Community Resource Management, Faculty of Family and Community Sciences, The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, Vadodara, Gujarat, INDIA Available online at: www.isca.in, www.isca.me Received 6th May 2014, revised 21 st August 2014, accepted 19 th September 2014 Abstract Today the restaurant industry is developing very rapidly. The review of literature has highlighted that there exist a number of “theme restaurant” outside India. Few, such types of restaurants were found in India too. The colonial theme reflecting the British era of Kolkata was yet not found in India and specially in Vadodara which inspired the designer to undertake the present design project with the objectives of a).Identifying the famous historical colonial monuments of British era in Kolkatta. b).Studying the interior features used in the selected colonial monuments of the British era of Kolkatta city. The observation sheet was used to gather the details for developing case studies on the existing interior features of the monuments. The findings of the case studies highlighted that the colonial monuments were having white colored walls. The existing floors were made up of wood and in majority of areas it was made up of marble and granite with geometrical pattern in them. The walls of the monuments were having mouldings. In the name of furnishings and lightings, the lights were replaced by the new lights and there were no furnishings. -

5. Park Street HPO

5. Park Street HPO Sl. No. Beat No. Name of the Postmen Photograph Contact No. Delivery Beat Area 111 TO 119(ODD) PARK STREET , 30 TO 48 (EVEN ) PARK STREET * 1 1 ALAMGIR BISWAS 9732547994 FOR SPEED POST ARTICLE* SUDDER STREET (FULL),MADGE LANE ( FULL), HARTFORT LANE 2 2 INDRAJIT BISWAS 8926282918 (FULL),COWIE LANE(FULL), STUART LANE(FULL), TOTTE LANE(FULL),27 J L NEHRU ROAD * FOR SPEED POST ARTICLE* 20 TO 24 (EVEN) PARK STREET,3 TO 57 (ODD) PARK STREET * FOR 3 3 KASHI NATH GHOSH 9064058171 SPEED POST ARTICLE* 2 TO 10 (EVEN) ROYD STREET, 1 T0 21B (ODD) ROYD STREET, 42A TO 4 4 SANATAN BISAI 9609336793 52/1 RAFI AHMED KIDWAI ROAD, PARK LANE ( FULL), ROYD LANE ( FULL),COOKBURN LANE * FOR SPEED POST ARTICLE* 20 TO 122 (EVEN) ELLIOT ROAD , 55 TO 95 (ODD) ELLIOT ROAD, 12 5 5 BASANTA PARIA 9547303378 TO 24(EVEN) ROYD STREET * FOR SPEED POST ARTICLE* 1, 7,15, 6/1 WOOD STREET, 22.24 CAMAC STREET, 1,6A,9A,11 6 6 JAGABANDU GORAI 7063600394 SHORT STREET, 1,2/1,20,22A LOUDAN STREET * FOR SPEED POST ARTICLE* 20-37 ALIMUDDIN STREET,16 SANDAL STREET,1-9 RIPON SQUARE , 1- 15 ,22-35 SHERIF LANE ,4,4/1,4/2 NAWAB ABDUL LETIF STREET, 47- 7 7 SUBIR MUSHIB 7872289700 74/2 A J C BOSE ROAD,47-88/2 RIPON STREET * FOR SPEED POST ARTICLE* CHOWRINGHEE LANE ( FULL), MARQUIS STREET (FULL),32-56D 8 8 PULAK MANDAL 8240580566 (EVEN) MIRZA GHALIB STREET,13 D - 43 (ODD) MIRZA GHALIB STREET * FOR SPEED POST ARTICLE* 57A-71 (ODD) PARK STREET , 45 -57 (ODD) MIRZA GHALIB STREET, 1- 9 9 ALOKE DUTTA 6289857497 9 & 13-18 COLLIN LANE, SYED ISMAIL LANE (FULL) * FOR SPEED POST ARTICLE* -

List of Litigation of Property SL

List of Litigation of Property SL. PREMISES NO. & ASSESSEE NAME OF RO NATURE OF CASE PENDING SOURCE OF NO. NO. LITIGATION AT COURT (SUIT INFORMATION NO & WP NO) 1 PRS: 26 Ganga Prosad Est. Charusila Mitra, Sri subjective T.S No- 11258 Letter from Mukherjee Road. A) No- Prokash ch. Mitra, Sri property of 2012 Debojyoti Mitra. 110720900269 Debojyoti mitra, Sm. Pending before Debjani Mitra, Smt. LD. Civil judge Debooree Mitra. 4th At Alipore 2 53/11 Durga Charan Estate Purna Chandra Personal NIL Letter from Doctor Lane Coomar ,Amal Request Jacqueline Gomes. 110530800910 Chakraborty P/L: Jacqueline Gomes,Noela Sreeja Biswas 3 63B Ballygunje Garden Ranjita Moulick Personal NIL Letter from Adv. 110680301402 Request Ujjwal Kumar Das on behalf of Debabrata Mall. 4 46B, Chowringhee The Dunlop Rubber India Subjudice CP No -233 of Letter from Dy. Road. 110631000216 co. of Limited & M/S Property. 2008 Official Liquidator, Guest Keen Williams High court Limited Calcutta. 5 62A Mirza Ghalib Street M/S Dunlop India Subjudice CP No -233 of Letter from Dy. 110633200324 Limited. Property 2008 Official Liquidator, High court Calcutta. 6 46B Chowringhee Road Salasar Towers Pvt. Ltd. Subjudice CP No -233 of Letter from Dy. 110631003679 Property 2008 Official Liquidator, High court Calcutta. 7 20/1A Braunfield Row. Govt. of W.B Kolkata Personal NIL Leter from MD. 110780300644 Thika Tenaney Hut request Hasan Ali Attorney owner: Kamala Gupta & 9 of Sri Pratyush others Paul 8 3. Hungerford St. M/S V.J. Construction Subjudice C.S No- 12 of Letter from Smt. 140632300153 company Allottee: Smt. -

Oneway Regulation

ONEWAY REGULATION Guard Name Road Name Road New Oneway Oneway Direction Time Remarks Name Stretch Stretch1 BHAWANIPORE Baker Road Biplabi Kanai Entire Entire N-S 08.00- TRAFFIC GUARD Bhattacharya Sarani 20.00hrs BHAWANIPORE Chakraberia Pandit Modan From Sarat Bose From Sarat E-W 08.00- TRAFFIC GUARD Road (North) Mohan Malaviya Rd to B/ Circular Bose Rd to B/ 14.00hrs Sarani Rd Circular Rd BHAWANIPORE Elgin Road Lala Lajpat Rai Entire Entire W-E 14.00- TRAFFIC GUARD Sarani 20.00hrs BHAWANIPORE Harish Mukherjee Entire Entire N-S 14.00- TRAFFIC GUARD Road 21.00hrs BHAWANIPORE Harish Mukherjee Entire Entire S-N 08.00- TRAFFIC GUARD Road 14.00hrs BHAWANIPORE Hasting Park Entire Entire S-N 08.00- Except Sunday TRAFFIC GUARD Road 20.00hrs BHAWANIPORE Justice Ch Entire Entire E-W 14.00- TRAFFIC GUARD Madhab Road 20.00hrs BHAWANIPORE Justice Ch Entire Entire W-E 08.00- TRAFFIC GUARD Madhab Road 14.00hrs BHAWANIPORE Kali Temple Road Entire Entire E-W 08.00- TRAFFIC GUARD 14.00hrs BHAWANIPORE Kalighat Rd Manya Sardar B K Hazra Rd to Hazra Rd to N-S 08.00- TRAFFIC GUARD (portion) Maitra Road Harish Mukherjee Harish 14.00hrs Rd Mukherjee Rd BHAWANIPORE Kalighat Rd Manya Sardar B K Hazra Rd to Hazra Rd to S-N 14.00- TRAFFIC GUARD (portion) Maitra Road Harish Mukherjee Harish 21.00hrs Rd Mukherjee Rd BHAWANIPORE Lee Road O C Ganguly Sarani Entire Entire N-S 08.00- TRAFFIC GUARD 14.00hrs BHAWANIPORE Lee Road O C Ganguly Sarani Entire Entire S-N 14.00- TRAFFIC GUARD 21.00hrs BHAWANIPORE Motilal Nehru N-S 14.00- TRAFFIC GUARD Road 21.00hrs BHAWANIPORE -

Maulana Azad Library, Aligarh Muslim University

PUBLIC LIBRARY SYSTEM IN WEST BENGAL: AN EVALUATIVE STUDY THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy IN Library and Information Science BY SHAMIM AKTAR MUNSHI (Enrol. No. GD-2903) UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF DR. MEHTAB ALAM ANSARI (Associate Professor) Maulana Azad Library, Aligarh Muslim University DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY AND INFORMATION SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (U.P.) INDIA 2019 Department of Library & Information Science Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh Dr. Mehtab Alam Ansari Mob: +91 9358219781 (Associate Professor) E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] Dated: ………………………………… Certificate This is to certify that the thesis entitled “Public Library System in West Bengal: An Evaluative Study” Submitted by Mr. Shamim Aktar Munshi for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of Library and Information Science, is based on the research work carried out by him under my supervision and guidance. It is further certified that to the best of my knowledge, this work has not been submitted in any University or Institution for the award of any other degree or diploma. I deem it fit for submission. Dr. Mehtab Alam Ansari (Associate Professor) Maulana Azad Library, Aligarh Muslim University Postal Address: AB-55, Medical Colony, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh-202002 (U.P), India. Declaration I hereby declare that the thesis “Public Library System in West Bengal: An Evaluative Study” submitted for the award of degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Library and Information Science is based on my individual research effort, and the thesis has not been presented for the award of any other degree or diploma in any University or Institution, and that all the sources used in this research effort have been comprehensively acknowledged. -

AUCTION NOTICE Rs 200/-Rupess Two) Only

AUCTION NOTICE Rs 200/-Rupess Two) only No:_2/Pasturage/2016-17/TEN . Dated 08/01/.2016 Auction is invited by the Commissioner of Police, Kolkata for Pasturaging of Animal & Cutting of Grass on small shrubs in the Kolkata Maidan for the year 2016-2017 Bonafide Contractors appearing for Auction for the Pasturaging and Cutting of grass and small shrubs of the Kolkata Maidan Area for a period from 01.04.2016 to 31.03 .2017 should follow the following instructions. 1. Cutting of grass and pasturage of animals will not be permitted on the following areas of the Kolkata Maidans: - a) A track of 60(sixty) acres of the land on the south and south-east of the glacis of the Fort William reserved for Military Authorities. b) Ground within the boundaries of the Victoria Memorial Hall.. c) Portion of the land now occupied by the rubbing down Shades of the Royal Calcutta Turf Club and enclosed with railing as well as whole of the Race Course enclosures. d) Portion lying on the north of the Eden Garden and on the south of the Esplanade Row East and extending in front of High Court, Treasury and Town Hall Buildings. e) Places fenced around for either Beautification /Plantation or Fair /Exhibition /Religious programmes. f) Red Road camp areas. g) Land on either side of the Red Road between the balustrades. h) Road newly constructed in the Maidan areas. i) An area of 4.94 acres (200 metres X 100 metres) for the constructions of dancing Foundation on the south of the South West of Brigade Parade Ground and opposite to North of Victoria Memorial Hall. -

Full Text: DOI

Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities (ISSN 0975-2935) Indexed by Web of Science, Scopus, DOAJ, ERIHPLUS Themed Issue on “India and Travel Narratives” (Vol. 12, No. 3, 2020) Guest-edited by: Ms. Somdatta Mandal, PhD Full Text: http://rupkatha.com/V12/n3/v12n332.pdf DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.21659/rupkatha.v12n3.32 Representing Kolkata : A Study of ‘Gaze’ Construction in Amit Chaudhuri’s Calcutta: Two Years in the City and Bishwanath Ghosh’s Longing Belonging: An Outsider at Home in Calcutta Saurabh Sarmadhikari Assistant Professor, Department of English, Gangarampur College, Dakshin Dinajpur, West Bengal. ORCID: 0000-0002-8577-4878. Email: [email protected] Abstract Indian travel writings in English exclusively on Kolkata have been rare even though tourist guidebooks such as the Lonely Planet have dedicated sections on the city. In such a scenario, Amit Chaudhuri’s Calcutta: Two Years in the City (2016) and Bishwanath Ghosh’s Longing Belonging: An Outsider at Home in Calcutta (2014) stand out as exceptions. Both these narratives, written by probashi (expatriate) Bengalis, represent Kolkata though a bifocal lens. On the one hand, their travels are a journey towards rediscovering their Bengali roots and on the other, their representation/construction of the city of Kolkata is as hard-boiled as any seasoned traveller. The contention of this paper is that both Chaudhuri and Ghosh foreground certain selected/pre- determined signifiers that are common to Kolkata for the purpose of their representation which are instrumental in constructing the ‘gaze’ of their readers towards the city. This process of ‘gaze’ construction is studied by applying John Urry and Jonas Larsen’s conceptualization of the ‘tourist gaze’.