Miami1281218845.Pdf (444.5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Overview of Russian Foreign Policy

02-4498-6 ch1.qxd 3/25/02 2:58 PM Page 7 1 AN OVERVIEW OF RUSSIAN FOREIGN POLICY Forging a New Foreign Policy Concept for Russia Russia’s entry into the new millennium was accompanied by qualitative changes in both domestic and foreign policy. After the stormy events of the early 1990s, the gradual process of consolidating society around a strengthened democratic gov- ernment took hold as people began to recognize this as a requirement if the ongoing political and socioeconomic transformation of the country was to be successful. The for- mation of a new Duma after the December 1999 parliamen- tary elections, and Vladimir Putin’s election as president of Russia in 2000, laid the groundwork for an extended period of political stability, which has allowed us to undertake the devel- opment of a long-term strategic development plan for the nation. Russia’s foreign policy course is an integral part of this strategic plan. President Putin himself has emphasized that “foreign policy is both an indicator and a determining factor for the condition of internal state affairs. Here we should have no illusions. The competence, skill, and effectiveness with 02-4498-6 ch1.qxd 3/25/02 2:58 PM Page 8 which we use our diplomatic resources determines not only the prestige of our country in the eyes of the world, but also the political and eco- nomic situation inside Russia itself.”1 Until recently, the view prevalent in our academic and mainstream press was that post-Soviet Russia had not yet fully charted its national course for development. -

Charter of the Tibetans-In-Exile

CHARTER OF THE TIBETANS-IN-EXILE 1991 I Preface His Holiness the Dalai Lama has guided us towards a democratic system of government, in order that the Tibetan people in exile be able to preserve their ancient traditions of spiritual and temporal life, unique to the Tibetans, based on the principles of peace and non-violence, aimed at providing politi- cal, social and economic rights as well as the attainment of justice and equal- ity for all Tibetan people, Efforts shall be made to transform a future Tibet into a Federal Democratic Self-Governing Republic and a zone of peace throughout her three regions, Whereas in particular, efforts shall be made in promoting the achievement of Tibet’s common goal as well as to strengthen the solidarity of Tibetans, both within and outside of Tibet, and to firmly establish a democratic system suit- able to the temporary ideals of the Tibetan people. The Eleventh Assembly of Tibetan People’s Deputies do hereby promulgate and legalize this Charter of the Tibetans-in-Exile as their fundamental guide. Adopted on June 14, 1991; Second Day of the Fifth Tibetan Month, 2118 Ti- betan Royal Year. II Contents CHAPTER - I FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLES Article 1 - Commencement 6 Article 2 - Jurisdiction 6 Article 3 - Nature of the Tibetan Polity 6 Article 4 - Principles of the Tibetan Administration 6 Article 5 - Validity of the Charter 6 Article 6 - Recognition of International and Local Law 6 Article 7 - Renunciation of Violence and the Use of Force 6 Article 8 - Citizen of Tibet 6 CHAPTER - II FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS AND -

Cursed Days, a Diary of the Revolution'

H-Russia Rose on Bunin, 'Cursed Days, A Diary of the Revolution' Review published on Thursday, October 1, 1998 Ivan Bunin. Cursed Days, A Diary of the Revolution. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee Publisher, 1998. xiii + 286 pp. $28.50 (paper), ISBN 978-1-56663-186-0. Reviewed by Linda P. Rose (Graduate School of Education & Information Studies, University of California at Los Angeles) Published on H-Russia (October, 1998) Revolutionary Days: Still Cursed? Cursed Days, Ivan Bunin's diary/notebook written during and about the Russian Revolution and the Civil War, became immensely popular in Russia after the Soviets lost power through a bloodless revolution. Since 1991, no less than fifteen separate editions of Bunin's diary/notebook have been published in Russia. There can be many explanations for the diary/notebook's popularity. Bunin's diary/notebook and other works, along with the books of other Russian emigre authors, were banned by the Soviets by the end of the 1920's. Although they could not be bought in stores, these authors could not be eliminated from the hearts and minds of some Russians. With the Soviets' downfall, many sought to know more about the events that had occurred between 1918-1920. Another, perhaps more pressing motive for the readers was to understand more about their own evolving revolution. While the Bolsheviks' dependence on bloodshed to re-shape Russia has not been copied by their successors since the 1991 Revolution, ethnic strife, economic woes, and social upheaval have accompanied the revolution. The battles in Chechnya continue. Economic problems are common, and many public servants and the military personnel get sub-existence wages. -

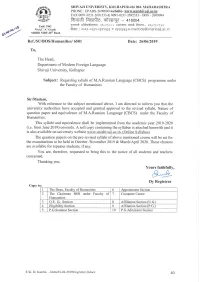

M.A. Russian 2019

************ B+ Accredited By NAAC Syllabus For Master of Arts (Part I and II) (Subject to the modifications to be made from time to time) Syllabus to be implemented from June 2019 onwards. 2 Shivaji University, Kolhapur Revised Syllabus For Master of Arts 1. TITLE : M.A. in Russian Language under the Faculty of Arts 2. YEAR OF IMPLEMENTATION: New Syllabus will be implemented from the academic year 2019-20 i.e. June 2019 onwards. 3. PREAMBLE:- 4. GENERAL OBJECTIVES OF THE COURSE: 1) To arrive at a high level competence in written and oral language skills. 2) To instill in the learner a critical appreciation of literary works. 3) To give the learners a wide spectrum of both theoretical and applied knowledge to equip them for professional exigencies. 4) To foster an intercultural dialogue by making the learner aware of both the source and the target culture. 5) To develop scientific thinking in the learners and prepare them for research. 6) To encourage an interdisciplinary approach for cross-pollination of ideas. 5. DURATION • The course shall be a full time course. • The duration of course shall be of Two years i.e. Four Semesters. 6. PATTERN:- Pattern of Examination will be Semester (Credit System). 7. FEE STRUCTURE:- (as applicable to regular course) i) Entrance Examination Fee (If applicable)- Rs -------------- (Not refundable) ii) Course Fee- Particulars Rupees Tuition Fee Rs. Laboratory Fee Rs. Semester fee- Per Total Rs. student Other fee will be applicable as per University rules/norms. 8. IMPLEMENTATION OF FEE STRUCTURE:- For Part I - From academic year 2019 onwards. -

Nostalgia and the Myth of “Old Russia”: Russian Émigrés in Interwar Paris and Their Legacy in Contemporary Russia

Nostalgia and the Myth of “Old Russia”: Russian Émigrés in Interwar Paris and Their Legacy in Contemporary Russia © 2014 Brad Alexander Gordon A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for completion Of the Bachelor of Arts degree in International Studies at the Croft Institute for International Studies Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College The University of Mississippi University, Mississippi April, 2014 Approved: Advisor: Dr. Joshua First Reader: Dr. William Schenck Reader: Dr. Valentina Iepuri 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………p. 3 Part I: Interwar Émigrés and Their Literary Contributions Introduction: The Russian Intelligentsia and the National Question………………….............................................................................................p. 4 Chapter 1: Russia’s Eschatological Quest: Longing for the Divine…………………………………………………………………………………p. 14 Chapter 2: Nature, Death, and the Peasant in Russian Literature and Art……………………………………………………………………………………..p. 26 Chapter 3: Tsvetaeva’s Tragedy and Tolstoi’s Triumph……………………………….........................................................................p. 36 Part II: The Émigrés Return Introduction: Nostalgia’s Role in Contemporary Literature and Film……………………………………………………………………………………p. 48 Chapter 4: “Old Russia” in Contemporary Literature: The Moral Dilemma and the Reemergence of the East-West Debate…………………………………………………………………………………p. 52 Chapter 5: Restoring Traditional Russia through Post-Soviet Film: Nostalgia, Reconciliation, and the Quest -

Shaken, Not Stirred: Markus Wolfâ•Žs Involvement in the Guillaume Affair

Voces Novae Volume 4 Article 6 2018 Shaken, not Stirred: Markus Wolf’s Involvement in the Guillaume Affair and the Evolution of Foreign Espionage in the Former DDR Jason Hiller Chapman University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/vocesnovae Recommended Citation Hiller, Jason (2018) "Shaken, not Stirred: Markus Wolf’s Involvement in the Guillaume Affair nda the Evolution of Foreign Espionage in the Former DDR," Voces Novae: Vol. 4 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/vocesnovae/vol4/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Voces Novae by an authorized editor of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hiller: Shaken, not Stirred: Markus Wolf’s Involvement in the Guillaume A Foreign Espionage in the Former DDR Voces Novae: Chapman University Historical Review, Vol 3, No 1 (2012) HOME ABOUT USER HOME SEARCH CURRENT ARCHIVES PHI ALPHA THETA Home > Vol 3, No 1 (2012) > Hiller Shaken, not Stirred: Markus Wolf's Involvement in the Guillaume Affair and the Evolution of Foreign Espionage in the Former DDR Jason Hiller "The principal link in the chain of revolution is the German link, and the success of the world revolution depends more on Germany than upon any other country." -V.I. Lenin, Report of October 22, 1918 The game of espionage has existed longer than most people care to think. However, it is not important how long ago it started or who invented it. What is important is the progress of espionage in the past decades and the impact it has had on powerful nations. -

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List Denotes new titles recently added to the list while the severity of her older sister's injuries Abuse and the urging of her younger sister, their uncle, and a friend tempt her to testify against Anderson, Laurie Halse him, her mother and other well-meaning Speak adults persuade her to claim responsibility. A traumatic event in the (Mature) (2007) summer has a devastating effect on Melinda's freshman Flinn, Alexandra year of high school. (2002) Breathing Underwater Sent to counseling for hitting his Avasthi, Swati girlfriend, Caitlin, and ordered to Split keep a journal, A teenaged boy thrown out of his 16-year-old Nick examines his controlling house by his abusive father goes behavior and anger and describes living with to live with his older brother, his abusive father. (2001) who ran away from home years earlier under similar circumstances. (Summary McCormick, Patricia from Follett Destiny, November 2010). Sold Thirteen-year-old Lakshmi Draper, Sharon leaves her poor mountain Forged by Fire home in Nepal thinking that Teenaged Gerald, who has she is to work in the city as a spent years protecting his maid only to find that she has fragile half-sister from their been sold into the sex slave trade in India and abusive father, faces the that there is no hope of escape. (2006) prospect of one final confrontation before the problem can be solved. McMurchy-Barber, Gina Free as a Bird Erskine, Kathryn Eight-year-old Ruby Jean Sharp, Quaking born with Down syndrome, is In a Pennsylvania town where anti- placed in Woodlands School in war sentiments are treated with New Westminster, British contempt and violence, Matt, a Columbia, after the death of her grandmother fourteen-year-old girl living with a Quaker who took care of her, and she learns to family, deals with the demons of her past as survive every kind of abuse before she is she battles bullies of the present, eventually placed in a program designed to help her live learning to trust in others as well as her. -

The Arts in Russia Under Stalin

01_SOVMINDCH1. 12/19/03 11:23 AM Page 1 THE ARTS IN RUSSIA UNDER STALIN December 1945 The Soviet literary scene is a peculiar one, and in order to understand it few analogies from the West are of use. For a vari- ety of causes Russia has in historical times led a life to some degree isolated from the rest of the world, and never formed a genuine part of the Western tradition; indeed her literature has at all times provided evidence of a peculiarly ambivalent attitude with regard to the uneasy relationship between herself and the West, taking the form now of a violent and unsatisfied longing to enter and become part of the main stream of European life, now of a resentful (‘Scythian’) contempt for Western values, not by any means confined to professing Slavophils; but most often of an unresolved, self-conscious combination of these mutually opposed currents of feeling. This mingled emotion of love and of hate permeates the writing of virtually every well-known Russian author, sometimes rising to great vehemence in the protest against foreign influence which, in one form or another, colours the masterpieces of Griboedov, Pushkin, Gogol, Nekrasov, Dostoevsky, Herzen, Tolstoy, Chekhov, Blok. The October Revolution insulated Russia even more com- pletely, and her development became perforce still more self- regarding, self-conscious and incommensurable with that of its neighbours. It is not my purpose to trace the situation histori- cally, but the present is particularly unintelligible without at least a glance at previous events, and it would perhaps be convenient, and not too misleading, to divide its recent growth into three main stages – 1900–1928; 1928–1937; 1937 to the present – artifi- cial and over-simple though this can easily be shown to be. -

Socialist Realism Seen in Maxim Gorky's Play The

SOCIALIST REALISM SEEN IN MAXIM GORKY’S PLAY THE LOWER DEPTHS AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By AINUL LISA Student Number: 014214114 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2009 SOCIALIST REALISM SEEN IN MAXIM GORKY’S PLAY THE LOWER DEPTHS AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By AINUL LISA Student Number: 014214114 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2009 i ii iii HHaappppiinneessss aallwwaayyss llooookkss ssmmaallll wwhhiillee yyoouu hhoolldd iitt iinn yyoouurr hhaannddss,, bbuutt lleett iitt ggoo,, aanndd yyoouu lleeaarrnn aatt oonnccee hhooww bbiigg aanndd pprreecciioouuss iitt iiss.. (Maxiim Gorky) iv Thiis Undergraduatte Thesiis iis dediicatted tto:: My Dear Mom and Dad,, My Belloved Brotther and Siistters.. v vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly, I would like to praise Allah SWT for the blessings during the long process of this undergraduate thesis writing. I would also like to thank my patient and supportive father and mother for upholding me, giving me adequate facilities all through my study, and encouragement during the writing of this undergraduate thesis, my brother and sisters, who are always there to listen to all of my problems. I am very grateful to my advisor Gabriel Fajar Sasmita Aji, S.S., M.Hum. for helping me doing my undergraduate thesis with his advice, guidance, and patience during the writing of my undergraduate thesis. My gratitude also goes to my co-advisor Dewi Widyastuti, S.Pd., M.Hum. -

OSLO Casting Announcement

MICHAEL ARONOV, ADAM DANNHEISSER, JENNIFER EHLE, DANIEL JENKINS, DARIUSH KASHANI, JEFFERSON MAYS, DANIEL ORESKES, HENNY RUSSELL, JOSEPH SIRAVO, T. RYDER SMITH TO BE FEATURED IN THE LINCOLN CENTER THEATER PRODUCTION OF “OSLO” a new play by J.T. ROGERS directed by BARTLETT SHER PREVIEWS BEGIN THURSDAY, JUNE 16 OPENING NIGHT IS MONDAY, JULY 11 AT THE MITZI E. NEWHOUSE THEATER Lincoln Center Theater (under the direction of André Bishop) has announced that Michael Aronov, Adam Dannheisser, Jennifer Ehle, Daniel Jenkins, Dariush Kashani, Jefferson Mays, Daniel Oreskes, Henny Russell, Joseph Siravo, and T. Ryder Smith will be featured in the cast of its upcoming production of OSLO, a new play by J.T. Rogers, directed by Bartlett Sher. Commissioned by Lincoln Center Theater, OSLO begins performances Thursday, June 16 and will open Monday, July 11 at the Mitzi E. Newhouse Theater (150 West 65 Street). Additional casting will be announced at a later date. It’s 1993. The world watches the impossible: Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and Palestinian Liberation Organization Chairman Yasser Arafat, standing together in the White House Rose Garden, signing the first ever peace agreement between Israel and the PLO. How were the negotiations kept secret? Why were they held in a castle in the middle of Norway? And who are these mysterious negotiators? A darkly comic epic, OSLO tells the true, but until now, untold story of how one young couple, Norwegian diplomat Mona Juul (to be played by Jennifer Ehle) and her husband social scientist Terje Rød-Larsen (to be played by Jefferson Mays), planned and orchestrated top-secret, high-level meetings between the State of Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization, which culminated in the signing of the historic 1993 Oslo Accords. -

David Mandel

David Mandel (1990) The Petrograd Workers and the Fall of the Old Régime From the February Revolution to the July Days, 1917 Un document produit en version numérique par Mme Marcelle Bergeron, bénévole Professeure à la retraite de l’École Dominique-Racine de Chicoutimi, Québec Courriel : mailto : [email protected] Dans le cadre de la collection : "Les classiques des sciences sociales" dirigée et fondée par Jean-Marie Tremblay, professeur de sociologie au Cégep de Chicoutimi Site web : http://bibliotheque.uqac.ca/ Une collection développée en collaboration avec la Bibliothèque Paul-Émile-Boulet de l'Université du Québec à Chicoutimi Site web: http://classiques.uqac.ca David Mandel, The Petrograd Workers and the Fall of the Old Régime (1983) 2 Un document produit en version numérique par Mme Marcelle Bergeron, bénévole, professeure à la retraite de l’École Dominique-Racine de Chicoutimi, Québec courriel : mailto:[email protected] David Mandel Une édition électronique réalisée à partir du texte de David Mandel, The Petrograd workers and the Fall of the Old Régime. From the February Revolution to the July Days, 1917. London: MACMILLAN, Macmillan Academic and Professional Ltd., in association with the Centre for Russian and East European Studies University of Birmingham. 1st edition, 1983. Reprinted, 1990, 220 pp. + 10 pp. [Autorisation accordée par l'auteur le 13 décembre 2006 de diffuser ce livre dans Les Classiques des sciences sociales.] Courriels : [email protected] ou [email protected]. Polices de caractères utilisés : Pour le texte : Times New Roman, 12 points. Pour les citations : Times New Roman 10 points. Pour les notes de bas de page : Times New Roman, 10 points. -

Round 12.Pdf

Cavalier Classic XII Round 12 Page 2 of 10 Tossups I . A poem of this man's is the basis of Canadian engineering schools' "Iron Ring" graduation ceremony. "Puck of Pook's Hill" tells stories of England, but collections like "Barrack Room Ballads- and "The Phantom Rickshaw" discuss his native land. Novels include The Light That Failed. which incorporated themes of the British Empire, an institution this author critiqued in "Recessional- but supported in "The White Man's Burden." FTP, name this author of "The Man Who Would be King," "If-." "Gunga Din," and The Jungle Book. Answer: Rudyard Kipling 2. A morning engagement here between Hooker's and Jackson's forces north of Dunker Church saw thousands of casualties at West Woods and the Cornfield. In the afternoon, Burnside's attack on Longstreet's men was delayed by a costly and time-consuming assault on a bridge. Between these two engagements was almost four hours of fighting for a sunken road, later given the name "Bloody Lane." Resulting in Lee's retreat across the Potomac, FIT, name this Civil War battle in Maryland in which Union forces under McClellan triumphed, and which saw the most Americans killed in a single day in U.S. history. Answer: Battle of Antietam or Sharpsburg 3. One of their secondary functions is to help repair damage to the cell membrane by sealing off wounds. The membrane surrounding them keeps their contents, at a pH of 4.8, from destroying the surrounding cell. Their primary function is used in phagocytosis, endocytosis, and autophagy. FTP, what are these cellular organelles, whose job it is to digest other organelles and foreign particles? Answer: lysosomes 4.