The Translingual Creativity of Chinese University Students in an Academic Writing Course

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Last Name First Name/Middle Name Course Award Course 2 Award 2 Graduation

Last Name First Name/Middle Name Course Award Course 2 Award 2 Graduation A/L Krishnan Thiinash Bachelor of Information Technology March 2015 A/L Selvaraju Theeban Raju Bachelor of Commerce January 2015 A/P Balan Durgarani Bachelor of Commerce with Distinction March 2015 A/P Rajaram Koushalya Priya Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Hiba Mohsin Mohammed Master of Health Leadership and Aal-Yaseen Hussein Management July 2015 Aamer Muhammad Master of Quality Management September 2015 Abbas Hanaa Safy Seyam Master of Business Administration with Distinction March 2015 Abbasi Muhammad Hamza Master of International Business March 2015 Abdallah AlMustafa Hussein Saad Elsayed Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Abdallah Asma Samir Lutfi Master of Strategic Marketing September 2015 Abdallah Moh'd Jawdat Abdel Rahman Master of International Business July 2015 AbdelAaty Mosa Amany Abdelkader Saad Master of Media and Communications with Distinction March 2015 Abdel-Karim Mervat Graduate Diploma in TESOL July 2015 Abdelmalik Mark Maher Abdelmesseh Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Master of Strategic Human Resource Abdelrahman Abdo Mohammed Talat Abdelziz Management September 2015 Graduate Certificate in Health and Abdel-Sayed Mario Physical Education July 2015 Sherif Ahmed Fathy AbdRabou Abdelmohsen Master of Strategic Marketing September 2015 Abdul Hakeem Siti Fatimah Binte Bachelor of Science January 2015 Abdul Haq Shaddad Yousef Ibrahim Master of Strategic Marketing March 2015 Abdul Rahman Al Jabier Bachelor of Engineering Honours Class II, Division 1 -

Electronic Supplementary Information a Versatile Bottom-Up Interface Self-Assembly Strategy to Hairy Nanoparticle-Based 2D Monol

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Chemical Communications. This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2019 Electronic Supplementary Information A versatile bottom-up interface self-assembly strategy to hairy nanoparticle-based 2D monolayered composite and functional nanosheets Weicong Mai, Yuan Zuo, Xingcai Zhang, Kunyi Leng, Ruliang Liu, Luyi Chen, Xidong Lin, Yanhuan Lin, Ruowen Fu, and Dingcai Wu* Materials Science Institute, Key Laboratory for Polymeric Composite and Functional Materials of Ministry of Education, School of Chemistry, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou 510275, P. R. China Experimental Section Materials. Styrene (St; Aladdin, AR), tert-butyl acrylate (tBA; Aladdin, 99%) and 4-vinylpyridine (Aladdin, 96%) were purified by passing through a basic alumina column. Copper(I) bromide (Aladdin, AR) was purified by washing sequentially with acetic acid and ethanol, filtration and drying, and was stored under nitrogen before use. Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS; Aladdin, AR), copper(II) bromide (Aladdin, AR), N,N,N′,N′,N′′-pentamethyldiethylenetriamine (PMDETA; Aladdin, 99%), Tris[2-(dimethylamino)ethyl]amine (Me6TREN; Aladdin, 98%), 3- aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES; Aladdin, AR), 2-bromoisobutyryl bromide (BIBB; Aladdin, AR) and other reagents were used as received. Synthesis of SiO2-Br nanoparticles. SiO2 nanoparticles were synthesized according to a previously 1 reported method. First, ethanol (400 mL) and NH3·H2O (25 wt % in water, 21 mL) were mixed in a three-necked round-bottom flask and stirred for 10 min at 40 °C. Then 20 mL TEOS was added and stirred for 10 h at 40 °C to obtain SiO2 nanoparticles with a diameter of 50 nm. 4 ml of APTES was dropped in a three-necked flask for 2 h and then the temperature was raised to 85 °C for 3 h. -

Ideophones in Middle Chinese

KU LEUVEN FACULTY OF ARTS BLIJDE INKOMSTSTRAAT 21 BOX 3301 3000 LEUVEN, BELGIË ! Ideophones in Middle Chinese: A Typological Study of a Tang Dynasty Poetic Corpus Thomas'Van'Hoey' ' Presented(in(fulfilment(of(the(requirements(for(the(degree(of(( Master(of(Arts(in(Linguistics( ( Supervisor:(prof.(dr.(Jean=Christophe(Verstraete((promotor)( ( ( Academic(year(2014=2015 149(431(characters Abstract (English) Ideophones in Middle Chinese: A Typological Study of a Tang Dynasty Poetic Corpus Thomas Van Hoey This M.A. thesis investigates ideophones in Tang dynasty (618-907 AD) Middle Chinese (Sinitic, Sino- Tibetan) from a typological perspective. Ideophones are defined as a set of words that are phonologically and morphologically marked and depict some form of sensory image (Dingemanse 2011b). Middle Chinese has a large body of ideophones, whose domains range from the depiction of sound, movement, visual and other external senses to the depiction of internal senses (cf. Dingemanse 2012a). There is some work on modern variants of Sinitic languages (cf. Mok 2001; Bodomo 2006; de Sousa 2008; de Sousa 2011; Meng 2012; Wu 2014), but so far, there is no encompassing study of ideophones of a stage in the historical development of Sinitic languages. The purpose of this study is to develop a descriptive model for ideophones in Middle Chinese, which is compatible with what we know about them cross-linguistically. The main research question of this study is “what are the phonological, morphological, semantic and syntactic features of ideophones in Middle Chinese?” This question is studied in terms of three parameters, viz. the parameters of form, of meaning and of use. -

From Translation to Adaptation: Chinese Language Texts and Early Modern Japanese Literature

From Translation to Adaptation: Chinese Language Texts and Early Modern Japanese Literature Nan Ma Hartmann Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Nan Ma Hartmann All rights reserved ABSTRACT From Translation to Adaptation: Chinese Language Texts and Early Modern Japanese Literature Nan Ma Hartmann This dissertation examines the reception of Chinese language and literature during Tokugawa period Japan, highlighting the importation of vernacular Chinese, the transformation of literary styles, and the translation of narrative fiction. By analyzing the social and linguistic influences of the reception and adaptation of Chinese vernacular fiction, I hope to improve our understanding of genre development and linguistic diversification in early modern Japanese literature. This dissertation historically and linguistically contextualizes the vernacularization movements and adaptations of Chinese texts in the seventeenth to eighteenth centuries, showing how literary importation and localization were essential stimulants and also a paradigmatic shift that generated new platforms for Japanese literature. Chapter 1 places the early introduction of vernacular Chinese language in its social and cultural contexts, focusing on its route of propagation from the Nagasaki translator community to literati and scholars in Edo, and its elevation from a utilitarian language to an object of literary and political interest. Central figures include Okajima Kazan (1674-1728) and Ogyû Sorai (1666-1728). Chapter 2 continues the discussion of the popularization of vernacular Chinese among elite intellectuals, represented by the Ken’en School of scholars and their Chinese study group, “the Translation Society.” This chapter discusses the methodology of the study of Chinese by surveying a number of primers and dictionaries compiled for reading vernacular Chinese and comparing such material with methodologies for reading classical Chinese. -

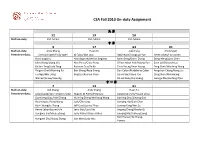

CSA Fall 2010 On-Duty Assignment

CSA Fall 2010 On-duty Assignment 九 月 12 19 26 Staff-on-duty: CSA Admin CSA Admin CSA Admin 十 月 3 17 24 31 Staff-on-duty: Andy Zhang Huan Yu Judy Tang Emily Sperl Parents-on-duty: Gerhard Sperl/Emily Sperl Al Falco/Wei Guo Bob Beach/Dongxian Yue Derek Olsen/Lixin Olsen Hua Jiang/Li Li Alan Baginski/Jessica Baginski Bolin Geng/Danni Zhong Dong Meng/Lynn Chen John Wang/Liying Wu Alex Perez/Clara Perez Chhun Maur Yon/Houng Yon Evan Lai/Deborah Lai Kuilian Tang/Judy Tang Baonian Guo/Jia Ke Chris Young/Yean Young Feng Chen/Wenfeng Wang Pingyin Chai/Wenning Fu Ben Sheng/Rose Sheng Dan Colon/Madeleine Colon Fengchun Chang/Hong Liu Tai Ngo/Mei Deng Bing Liu/Xuenan Yuan Daniel Hu/Yanna Yau Gang Shen/Min Huang Warren/Grace/ Saw Ng Daniel Ruan/Ivy Huang George Zhu/Lanfang Qiao 十 一 月 7 14 21 Staff-on-duty: Dili Zhang Andy Zhang Huan Yu Parents-on-duty: Greg (Gang) Sun/Fenyen Chang Hugues St Pierre/Ping Cao Jiangrong Chen/Yujuan Zhou Guanliang Qiau/Haili Zhang Huiming Zhang/Weihong Wang Jianning Zhu/Qinying Gao Haisheng Lu/Rong Wang Jack/Chio Ling Jianqing Hu/Qian Chen Hanli Wang/Ju Zhang Jeff Gao/Quzzna Zhao Jicneng Yang/Wei Su Henry Lebensbaum/n/a Jerry Guo/Lucy Xie Jingang Zhang/Xiaolei Qi Hongwei Shi/Minjie Zhang Jerry Palma/Grace Palma Junqing Ma/Huihong Song Karl Hoover/Jie Zhang- Hongwei Zhu/Xiaoqi Zhang Jian Wen/Judy Hou Hoover CSA Fall 2010 On-duty Assignment 十 二 月 5 12 19 Staff-on-duty: Judy Tang Emily Sperl Dili Zhang Parents-on-duty: Kenric Anderberg/Margaret Mick Verga/Ping Verga San Liang/Feiyan Zhao Anderberg Khia Tung/Aimy Tung Ming -

Chinese Language and Characters

Chinese Language and Characters Pronunciation of Chinese Words Consonants Pinyin WadeGiles Pronunciation Example: Pinyin(WadeGiles) Aspirated: p p’ pin Pao (P’ao) t t’ tip Tao (T’ao) k k’ kilt Kuan (K’uan) ch ch’ ch in, ch urch Chi (Ch’i) q ch’ ch eek Qi (Ch’i) c ts’ bi ts Cang (Ts’ang) Un- b p bin Bao (Pao) aspirated: d t dip Dao (Tao) g k gilt Guan (Kuan) r j wr en Ren (Jen) sh sh sh ore Shang (Shang) si szu Si (Szu) x hs or sh sh oe Xu (Hsu) z ts or tz bi ds Zang (Tsang) zh ch gin Zhong (Chong) zh j jeep Zhong (Jong) zi tzu Zi (Tzu) Vowels - a a father usually Italian e e ei ght values eh eh broth er yi i mach ine, p in Yi (I) i ih sh ir t Zhi (Chih) o soap u goo se ü über Dipthongs ai light ao lou d ei wei ght ia Will ia m ieh Kor ea ou gr ou p ua swa n ueh do er ui sway Hui (Hui) uo Whoah ! Combinations ian ien Tian (Tien) ui wei Wei gh Shui (Shwei) an and ang bun and b ung en and eng wood en and am ong in and ing sin and s ing ong un and ung u as in l oo k Tong (T’ung) you yu Watts, Alan; Tao The Watercourse Way, Pelican Books, 1976 http://acc6.its.brooklyn.cuny.edu/~phalsall/texts/chinlng1.html Tones 1 2 3 4 ā á ă à ē é ĕ È è Ī ī í ĭ ì ō ó ŏ ò ū ú ŭ ù Pinyin (Wade Giles) Meaning Ai Bā (Pa) Eight, see Numbers Bái (Pai) White, plain, unadorned Băi (Pai) One hundred, see Numbers Bāo Envelop Bāo (Pao) Uterus, afterbirth Bēi Sad, Sorrow, melancholy Bĕn Root, origin (Biao and Ben) see Biao Bi Bi (bei) Bian Bi āo Tip, dart, javelin, (Biao and Ben) see Ben Bin Bin Bing Bu Bu Can Cang Cáng (Ts’ang) Hidden, concealed (see Zang) Cháng Intestine Ch ōng (Ch’ung) Surging Ch ōng (Ch’ung) Rushing Chóu Worry Cóng Follow, accord with Dăn (Tan) Niche or shrine Dăn (Tan) Gall Bladder Dān (Tan) Red Cinnabar Dào (Tao) The Way Dì (Ti) The Earth, i.e. -

Performing Chinese Contemporary Art Song

Performing Chinese Contemporary Art Song: A Portfolio of Recordings and Exegesis Qing (Lily) Chang Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Elder Conservatorium of Music Faculty of Arts The University of Adelaide July 2017 Table of contents Abstract Declaration Acknowledgements List of tables and figures Part A: Sound recordings Contents of CD 1 Contents of CD 2 Contents of CD 3 Contents of CD 4 Part B: Exegesis Introduction Chapter 1 Historical context 1.1 History of Chinese art song 1.2 Definitions of Chinese contemporary art song Chapter 2 Performing Chinese contemporary art song 2.1 Singing Chinese contemporary art song 2.2 Vocal techniques for performing Chinese contemporary art song 2.3 Various vocal styles for performing Chinese contemporary art song 2.4 Techniques for staging presentations of Chinese contemporary art song i Chapter 3 Exploring how to interpret ornamentations 3.1 Types of frequently used ornaments and their use in Chinese contemporary art song 3.2 How to use ornamentation to match the four tones of Chinese pronunciation Chapter 4 Four case studies 4.1 The Hunchback of Notre Dame by Shang Deyi 4.2 I Love This Land by Lu Zaiyi 4.3 Lullaby by Shi Guangnan 4.4 Autumn, Pamir, How Beautiful My Hometown Is! by Zheng Qiufeng Conclusion References Appendices Appendix A: Romanized Chinese and English translations of 56 Chinese contemporary art songs Appendix B: Text of commentary for 56 Chinese contemporary art songs Appendix C: Performing Chinese contemporary art song: Scores of repertoire for examination Appendix D: University of Adelaide Ethics Approval Number H-2014-184 ii NOTE: 4 CDs containing 'Recorded Performances' are included with the print copy of the thesis held in the University of Adelaide Library. -

UC GAIA Chen Schaberg CS5.5-Text.Indd

Idle Talk New PersPectives oN chiNese culture aNd society A series sponsored by the American Council of Learned Societies and made possible through a grant from the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange 1. Joan Judge and Hu Ying, eds., Beyond Exemplar Tales: Women’s Biography in Chinese History 2. David A. Palmer and Xun Liu, eds., Daoism in the Twentieth Century: Between Eternity and Modernity 3. Joshua A. Fogel, ed., The Role of Japan in Modern Chinese Art 4. Thomas S. Mullaney, James Leibold, Stéphane Gros, and Eric Vanden Bussche, eds., Critical Han Studies: The History, Representation, and Identity of China’s Majority 5. Jack W. Chen and David Schaberg, eds., Idle Talk: Gossip and Anecdote in Traditional China Idle Talk Gossip and Anecdote in Traditional China edited by Jack w. cheN aNd david schaberg Global, Area, and International Archive University of California Press berkeley los Angeles loNdoN The Global, Area, and International Archive (GAIA) is an initiative of the Institute of International Studies, University of California, Berkeley, in partnership with the University of California Press, the California Digital Library, and international research programs across the University of California system. University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. -

Chinese Landscape Aesthetics: the Exchange and Nurturing of Emotions’, In: Kehrer, J

Text published as: Westermann, C. (2020), `Chinese Landscape Aesthetics: the Exchange and Nurturing of Emotions’, In: Kehrer, J. (ed.), New Horizons: Eight Perspectives on Chinese Landscape Architecture Today, Basel: Birkhäuser, pp. 34-37. Chinese Landscape Aesthetics The Exchange and Nurturing of Emotions Claudia Westermann Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University And high over the willows, the fine birds sing to each other, and listen, Crying – “Kwan, Kuan,” for the early wind, and the feel of it. The wind bundles itself into a bluish cloud and wanders off. Over a thousand gates, over a thousand doors are the sounds of spring singing, And the Emperor is at Ko. Excerpt of The River Song, by Li Bai, 8th century CE, translated by Ezra Pound1. The Chinese language has a variety of terms that are typically translated into English as landscape. There is 景观 jǐng guān – scenery view. An old meaning of 景 jǐng is light, luminous. So, literally 景观 jǐng guān means luminous view. The term is generally used when referring to foreign educational programmes in landscape architecture. Traditionally, university departments in China indicate an engagement with ideas of landscape with the characters 园林 yuán lín – garden forests. These are the characters for the classical Chinese gardens. The characters 风景 fēng jǐng, that literally translate to wind scenery, or wind light as the French sinologist François Jullien suggests2, are also fairly common. Landscape in painting is referred to as 山水 shān shuǐ – mountain(s) water(s) – but also as 山川 shān chuān – mountain(s) river(s). The attentive reader will have noticed that the Chinese language always employs a pair of characters to refer to landscape. -

Men's Sexual and Prostate Problems in Chinese Medicine

‘Traditional created by Formulae for the ® Modern World’ MEN’S SEXUAL AND PROSTATE PROBLEMS IN CHINESE MEDICINE While Chinese medicine has a rich tradition in the diagnosis and treatment of gynaecological problems, fewer ancient or modern texts are dedicated to the diagnosis and treatment of men’s problems. For example, Chinese medicine refers to the “Uterus” in all its classic texts, but no mention is ever made of the prostate. The Du Mai, Ren Mai and Chong Mai are said to arise in the Lower Burner and flow through the uterus: but where do they flow through in men? The classics do not say. The present newsletter will discuss the physiology of men’s sexual organs including the prostate, some aspects of pathology and the treatment of the following conditions: • Impotence • Premature ejaculation • Low sperm count • Benign prostatic hypertrophy • Prostatitis Before discussing the treatment of specific conditions, we should look at the channels that affect men’s genital system and how the penis, testis, seminal vesicles and prostate fit in Chinese Medicine. Chapter 65 of the “Spiritual Axis” says: “The Directing and Penetrating Vessels originate from the Lower Dan Tian [literally”Bao”].”1. 1981 Spiritual Axis (Ling Shu Jing [#ch]), People’s Health Publishing House, Beijing, p. 120. First published c. 100 BC. The actual term used by the “Spiritual Axis” is “Bao” which is often translated as “uterus”. However, while the term “Zi Bao” refers to the Uterus, the word “Bao” indicates a structure that is common to both men and women: in women, it is the Uterus, in men, it is the “Room of Sperm”. -

Chinese Romanization Table

239 Chinese Romanization Table Common Alphabetic (CA) follows the formula “consonants as in English, vowels as in Italian,” plus æ as in “cat,” v [compare the linguist’s !] as in “gut,” z as in “adz,” and yw (after l or n, simply w) for “umlaut u.” A lost initial ng- is restored to distinguish the states of We"! !! and Ngwe"! !!, both now “We"!.” Tones are h#!gh, r$!sing, lo%w, and fa"lling. The other systems are Pinyin (PY) and Wade-Giles (WG). CA PY WG CA PY WG a a a chya qia ch!ia ai ai ai chyang qiang ch!iang an an an chyau qiao ch!iao ang ang ang chye qie ch!ieh ar er erh chyen qian ch!ien au ao ao chyou qiu ch!iu ba ba pa chyung qiong ch!iung bai bai pai chyw qu ch!ü ban ban pan chywæn quan ch!üan bang bang pang chywe que ch!üeh bau bao pao chywn qun ch!ün bei bei pei da da ta bi bi pi dai dai tai bin bin pin dan dan tan bing bing ping dang dang tang bu bu pu dau dao tao bvn ben pen dei dei tei bvng beng peng di di ti bwo bo po ding ding ting byau biao piao dou dou tou bye bie pieh du du tu byen bian pien dun dun tun cha cha ch!a dung dong tung chai chai ch!ai dv de te chan chan ch!an dvng deng teng chang chang ch!ang dwan duan tuan chau chao ch!ao dwei dui tui chi qi ch!i dwo duo to chin qin ch!in dyau diao tiao ching qing ch!ing dye die tieh chou chou ch!ou dyen dian tien chr chi ch!ih dyou diu tiu chu chu ch!u dz zi tzu chun chun ch!un dza za tsa chung chong ch!ung dzai zai tsai chv che ch!e dzan zan tsan chvn chen ch!en dzang zang tsang chvng cheng ch!eng dzau zao tsao chwai chuai ch!uai dzei zei tsei chwan chuan ch!uan dzou -

Language, Likeness, and the Han Phenomenon of Convergence

Language, Likeness, and the Han Phenomenon of Convergence The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Vihan, Jan. 2012. Language, Likeness, and the Han Phenomenon of Convergence. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:9830346 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA © 2012 - Jan Vihan All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Prof. Michael Puett Jan Vihan Language, Likeness, and the Han Phenomenon of Convergence Abstract Although in the classical Chinese outlook the world can only be made sense of through the means devised by the ancient sages and handed down by the tradition, the art of exegesis has long been a neglected subject. Scholars have been all too eager to dispute what their chosen text says than to pay attention to the nuanced ways in which it hones its tools. This dissertation aims to somewhat redirect the discipline's attention by focusing on Xu Shen's Shuowen Jiezi . I approach this compendium of Han philology, typically regarded as a repository of disparate linguistic data, as underlied by a tight theoretical framework reducible to one simple idea. I begin with the discussion of the competing visions of the six principles, for two millenia the basis of instruction in the arts of letters. I identify the relationship between abstraction and representation and the principle of convergence as the main points of contention.