Chinese Landscape Aesthetics: the Exchange and Nurturing of Emotions’, In: Kehrer, J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the Death Mystery of Huo Qubing, a Famous Cavalry General in the Western Han Dynasty

Journal of Frontiers of Society, Science and Technology DOI: 10.23977/jfsst.2021.010410 Clausius Scientific Press, Canada Volume 1, Number 4, 2021 An Analysis of the Death Mystery of Huo Qubing, a Famous Cavalry General in the Western Han Dynasty Liu Jifeng, Chen Mingzhi Shandong Maritime Vocational College, Weifang, 261000, Shandong, China Keywords: Huo qubing, Myth, Mysterious death Abstract: Throughout his whole lifetime, Huo Qubing created a myth of ancient war, and left an indelible mark in history. But, pitifully, he suddenly died during young age. His whole life was very short, and it seemed that Huo was born for war and died at the end of war. Although he implemented his great words and aspirations “What could be applied to get married, since the Huns haven’t been eliminated?”, and had no regrets for life, still, his mysterious death caused endless questions and intriguing reveries for later generations. 1. Introduction Huo Qubing, with a humble origin, was born in 140 B.C. in a single-parent family in Pingyang, Hedong County, which belongs to Linfen City, Shanxi Province now. He was an illegitimate child of Wei Shaoer, a female slave of Princess Pingyang Mansion, and Huo Zhongru, an inferior official. Also, he was a nephew-in-mother of Wei Qing, who was General-in-chief Serving as Commander-in-chief in the Western Han Dynasty. Huo Qubing was greatly influenced by his uncle Wei Qing. He was a famous military strategist and national hero during the period of Emperor Wudi of the Western Han Dynasty. He was fond of horse-riding and archery. -

Gateless Gate Has Become Common in English, Some Have Criticized This Translation As Unfaithful to the Original

Wú Mén Guān The Barrier That Has No Gate Original Collection in Chinese by Chán Master Wúmén Huìkāi (1183-1260) Questions and Additional Comments by Sŏn Master Sǔngan Compiled and Edited by Paul Dōch’ŏng Lynch, JDPSN Page ii Frontspiece “Wú Mén Guān” Facsimile of the Original Cover Page iii Page iv Wú Mén Guān The Barrier That Has No Gate Chán Master Wúmén Huìkāi (1183-1260) Questions and Additional Comments by Sŏn Master Sǔngan Compiled and Edited by Paul Dōch’ŏng Lynch, JDPSN Sixth Edition Before Thought Publications Huntington Beach, CA 2010 Page v BEFORE THOUGHT PUBLICATIONS HUNTINGTON BEACH, CA 92648 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. COPYRIGHT © 2010 ENGLISH VERSION BY PAUL LYNCH, JDPSN NO PART OF THIS BOOK MAY BE REPRODUCED OR TRANSMITTED IN ANY FORM OR BY ANY MEANS, GRAPHIC, ELECTRONIC, OR MECHANICAL, INCLUDING PHOTOCOPYING, RECORDING, TAPING OR BY ANY INFORMATION STORAGE OR RETRIEVAL SYSTEM, WITHOUT THE PERMISSION IN WRITING FROM THE PUBLISHER. PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY LULU INCORPORATION, MORRISVILLE, NC, USA COVER PRINTED ON LAMINATED 100# ULTRA GLOSS COVER STOCK, DIGITAL COLOR SILK - C2S, 90 BRIGHT BOOK CONTENT PRINTED ON 24/60# CREAM TEXT, 90 GSM PAPER, USING 12 PT. GARAMOND FONT Page vi Dedication What are we in this cosmos? This ineffable question has haunted us since Buddha sat under the Bodhi Tree. I would like to gracefully thank the author, Chán Master Wúmén, for his grace and kindness by leaving us these wonderful teachings. I would also like to thank Chán Master Dàhuì for his ineptness in destroying all copies of this book; thankfully, Master Dàhuì missed a few so that now we can explore the teachings of his teacher. -

Last Name First Name/Middle Name Course Award Course 2 Award 2 Graduation

Last Name First Name/Middle Name Course Award Course 2 Award 2 Graduation A/L Krishnan Thiinash Bachelor of Information Technology March 2015 A/L Selvaraju Theeban Raju Bachelor of Commerce January 2015 A/P Balan Durgarani Bachelor of Commerce with Distinction March 2015 A/P Rajaram Koushalya Priya Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Hiba Mohsin Mohammed Master of Health Leadership and Aal-Yaseen Hussein Management July 2015 Aamer Muhammad Master of Quality Management September 2015 Abbas Hanaa Safy Seyam Master of Business Administration with Distinction March 2015 Abbasi Muhammad Hamza Master of International Business March 2015 Abdallah AlMustafa Hussein Saad Elsayed Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Abdallah Asma Samir Lutfi Master of Strategic Marketing September 2015 Abdallah Moh'd Jawdat Abdel Rahman Master of International Business July 2015 AbdelAaty Mosa Amany Abdelkader Saad Master of Media and Communications with Distinction March 2015 Abdel-Karim Mervat Graduate Diploma in TESOL July 2015 Abdelmalik Mark Maher Abdelmesseh Bachelor of Commerce March 2015 Master of Strategic Human Resource Abdelrahman Abdo Mohammed Talat Abdelziz Management September 2015 Graduate Certificate in Health and Abdel-Sayed Mario Physical Education July 2015 Sherif Ahmed Fathy AbdRabou Abdelmohsen Master of Strategic Marketing September 2015 Abdul Hakeem Siti Fatimah Binte Bachelor of Science January 2015 Abdul Haq Shaddad Yousef Ibrahim Master of Strategic Marketing March 2015 Abdul Rahman Al Jabier Bachelor of Engineering Honours Class II, Division 1 -

The Translingual Creativity of Chinese University Students in an Academic Writing Course

Journal of Global Literacies, Technologies, and Emerging Pedagogies Volume VI, Issue II, October 2020, pp. 1120-1143 Zhai Nan, Mai Meng and Filial Piety: The Translingual Creativity of Chinese University Students in an Academic Writing Course Chaoran Wang* Indiana University Bloomington [email protected] Beth Lewis Samuelson * Indiana University Bloomington [email protected] Katherine Silvester* Indiana University Bloomington [email protected] Abstract: In this action research study, we explore how translingual resources can support creativity in a multilingual freshmen composition class in a US public university. We explore the efforts of two Chinese international students and their Chinese graduate * Chaoran Wang is a Ph.D. candidate in Literacy, Culture, and Language Education at Indiana University Bloomington. She is currently working as an Associate Instructor at Indiana University. * Beth Lewis Samuelson is Associate Professor of Literacy, Culture and Language Education in the Indiana University Bloomington School of Education. She specializes in teaching English to speakers of other languages and teaching world languages, with special attention to literacy and second language writing instruction. * Katherine Silvester is an assistant professor of English and coordinator of multilingual writing in the Indiana University Bloomington Composition Program. ISSN: 2168-1333 ©2020 1121 Nan, Meng, Piety/JOLTEP 6(2) pp. 1120-1143 student instructor to represent their linguistic and cultural identities within established pedagogical practices using translingual semiotic resources. They explore together how they can use their first language as a resource for academic writing, and in the process develop metalinguistic insights about the roles that their linguistic and cultural proficiency can play in academic communication. Our examination of the written artefacts and interviews with the students and instructor reveal how a translingual pedagogy can inspire multilingual speakers of English to make use of their own cultures and languages as resources for writing and teaching. -

Electronic Supplementary Information a Versatile Bottom-Up Interface Self-Assembly Strategy to Hairy Nanoparticle-Based 2D Monol

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Chemical Communications. This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2019 Electronic Supplementary Information A versatile bottom-up interface self-assembly strategy to hairy nanoparticle-based 2D monolayered composite and functional nanosheets Weicong Mai, Yuan Zuo, Xingcai Zhang, Kunyi Leng, Ruliang Liu, Luyi Chen, Xidong Lin, Yanhuan Lin, Ruowen Fu, and Dingcai Wu* Materials Science Institute, Key Laboratory for Polymeric Composite and Functional Materials of Ministry of Education, School of Chemistry, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou 510275, P. R. China Experimental Section Materials. Styrene (St; Aladdin, AR), tert-butyl acrylate (tBA; Aladdin, 99%) and 4-vinylpyridine (Aladdin, 96%) were purified by passing through a basic alumina column. Copper(I) bromide (Aladdin, AR) was purified by washing sequentially with acetic acid and ethanol, filtration and drying, and was stored under nitrogen before use. Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS; Aladdin, AR), copper(II) bromide (Aladdin, AR), N,N,N′,N′,N′′-pentamethyldiethylenetriamine (PMDETA; Aladdin, 99%), Tris[2-(dimethylamino)ethyl]amine (Me6TREN; Aladdin, 98%), 3- aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES; Aladdin, AR), 2-bromoisobutyryl bromide (BIBB; Aladdin, AR) and other reagents were used as received. Synthesis of SiO2-Br nanoparticles. SiO2 nanoparticles were synthesized according to a previously 1 reported method. First, ethanol (400 mL) and NH3·H2O (25 wt % in water, 21 mL) were mixed in a three-necked round-bottom flask and stirred for 10 min at 40 °C. Then 20 mL TEOS was added and stirred for 10 h at 40 °C to obtain SiO2 nanoparticles with a diameter of 50 nm. 4 ml of APTES was dropped in a three-necked flask for 2 h and then the temperature was raised to 85 °C for 3 h. -

Self-Study Syllabus on Chinese Foreign Policy

Self-Study Syllabus on Chinese Foreign Policy www.mandarinsociety.org PrefaceAbout this syllabus with China’s rapid economic policymakers in Washington, Tokyo, Canberra as the scale and scope of China’s current growth, increasing military and other capitals think about responding to involvement in Africa, China’s first overseas power,Along and expanding influence, Chinese the challenge of China’s rising power. military facility in Djibouti, or Beijing’s foreign policy is becoming a more salient establishment of the Asian Infrastructure concern for the United States, its allies This syllabus is organized to build Investment Bank (AIIB). One of the challenges and partners, and other countries in Asia understanding of Chinese foreign policy in that this has created for observers of China’s and around the world. As China’s interests a step-by-step fashion based on one hour foreign policy is that so much is going on become increasingly global, China is of reading five nights a week for four weeks. every day it is no longer possible to find transitioning from a foreign policy that was In total, the key readings add up to roughly one book on Chinese foreign policy that once concerned principally with dealing 800 pages, rarely more than 40–50 pages will provide a clear-eyed assessment of with the superpowers, protecting China’s for a night. We assume no prior knowledge everything that a China analyst should know. regional interests, and positioning China of Chinese foreign policy, only an interest in as a champion of developing countries, to developing a clearer sense of how China is To understanding China’s diplomatic history one with a more varied and global agenda. -

These Materials Correspond to the June 1 and June 8, 2020 Sessions

The Mandarin "Lunch and Learn 午间中文" is a free, online, weekly 'Read-Aloud' series for Chinese language learners of all levels. The series helps individuals learn and practice pronunciation in Mandarin, while engaging with Chinese literature, culture and history with fellow enthusiasts. Participants will enjoy live interactions with our language and cultural experts from home. The full playlist of Lunch and Learn sessions are available on YouTube. These materials correspond to the June 1 and June 8, 2020 sessions. Guan-guan Go the Ospreys, the Book of Songs 《关雎∙诗经》 If you like learning Chinese language, literature, or particularly Chinese poetry, you have to know the Book of Songs(《诗经》), the fountainhead of Chinese literature, a collection of 305 poems, the finest form at the time and even today in Chinese language, compiled by Confucius, who lived from 551 to 479 B.C. For over 2,000 years, educated men and women in Chinese culture must, at some point, read the poems in the Book of Songs. Guan-guan Go the Ospreys(《关雎》)is the very first poem in the Book of Songs. In addition to its literary importance, many phrases and cultural references in this short poem, such as “窈窕淑女”, “求之不得”, “悠哉悠哉”, “辗转反侧” are still commonly used in modern Chinese. The poem is also one of the earliest documents referring to the important role of music in Chinese tradition. The selected English translation is by James Legge, a Scottish sinologist, missionary, and scholar, best known as an early and prolific translator of Classical Chinese texts into English. He was the first Professor of Chinese at Oxford University (1876–1897). -

Ideophones in Middle Chinese

KU LEUVEN FACULTY OF ARTS BLIJDE INKOMSTSTRAAT 21 BOX 3301 3000 LEUVEN, BELGIË ! Ideophones in Middle Chinese: A Typological Study of a Tang Dynasty Poetic Corpus Thomas'Van'Hoey' ' Presented(in(fulfilment(of(the(requirements(for(the(degree(of(( Master(of(Arts(in(Linguistics( ( Supervisor:(prof.(dr.(Jean=Christophe(Verstraete((promotor)( ( ( Academic(year(2014=2015 149(431(characters Abstract (English) Ideophones in Middle Chinese: A Typological Study of a Tang Dynasty Poetic Corpus Thomas Van Hoey This M.A. thesis investigates ideophones in Tang dynasty (618-907 AD) Middle Chinese (Sinitic, Sino- Tibetan) from a typological perspective. Ideophones are defined as a set of words that are phonologically and morphologically marked and depict some form of sensory image (Dingemanse 2011b). Middle Chinese has a large body of ideophones, whose domains range from the depiction of sound, movement, visual and other external senses to the depiction of internal senses (cf. Dingemanse 2012a). There is some work on modern variants of Sinitic languages (cf. Mok 2001; Bodomo 2006; de Sousa 2008; de Sousa 2011; Meng 2012; Wu 2014), but so far, there is no encompassing study of ideophones of a stage in the historical development of Sinitic languages. The purpose of this study is to develop a descriptive model for ideophones in Middle Chinese, which is compatible with what we know about them cross-linguistically. The main research question of this study is “what are the phonological, morphological, semantic and syntactic features of ideophones in Middle Chinese?” This question is studied in terms of three parameters, viz. the parameters of form, of meaning and of use. -

From Translation to Adaptation: Chinese Language Texts and Early Modern Japanese Literature

From Translation to Adaptation: Chinese Language Texts and Early Modern Japanese Literature Nan Ma Hartmann Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Nan Ma Hartmann All rights reserved ABSTRACT From Translation to Adaptation: Chinese Language Texts and Early Modern Japanese Literature Nan Ma Hartmann This dissertation examines the reception of Chinese language and literature during Tokugawa period Japan, highlighting the importation of vernacular Chinese, the transformation of literary styles, and the translation of narrative fiction. By analyzing the social and linguistic influences of the reception and adaptation of Chinese vernacular fiction, I hope to improve our understanding of genre development and linguistic diversification in early modern Japanese literature. This dissertation historically and linguistically contextualizes the vernacularization movements and adaptations of Chinese texts in the seventeenth to eighteenth centuries, showing how literary importation and localization were essential stimulants and also a paradigmatic shift that generated new platforms for Japanese literature. Chapter 1 places the early introduction of vernacular Chinese language in its social and cultural contexts, focusing on its route of propagation from the Nagasaki translator community to literati and scholars in Edo, and its elevation from a utilitarian language to an object of literary and political interest. Central figures include Okajima Kazan (1674-1728) and Ogyû Sorai (1666-1728). Chapter 2 continues the discussion of the popularization of vernacular Chinese among elite intellectuals, represented by the Ken’en School of scholars and their Chinese study group, “the Translation Society.” This chapter discusses the methodology of the study of Chinese by surveying a number of primers and dictionaries compiled for reading vernacular Chinese and comparing such material with methodologies for reading classical Chinese. -

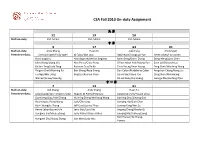

CSA Fall 2010 On-Duty Assignment

CSA Fall 2010 On-duty Assignment 九 月 12 19 26 Staff-on-duty: CSA Admin CSA Admin CSA Admin 十 月 3 17 24 31 Staff-on-duty: Andy Zhang Huan Yu Judy Tang Emily Sperl Parents-on-duty: Gerhard Sperl/Emily Sperl Al Falco/Wei Guo Bob Beach/Dongxian Yue Derek Olsen/Lixin Olsen Hua Jiang/Li Li Alan Baginski/Jessica Baginski Bolin Geng/Danni Zhong Dong Meng/Lynn Chen John Wang/Liying Wu Alex Perez/Clara Perez Chhun Maur Yon/Houng Yon Evan Lai/Deborah Lai Kuilian Tang/Judy Tang Baonian Guo/Jia Ke Chris Young/Yean Young Feng Chen/Wenfeng Wang Pingyin Chai/Wenning Fu Ben Sheng/Rose Sheng Dan Colon/Madeleine Colon Fengchun Chang/Hong Liu Tai Ngo/Mei Deng Bing Liu/Xuenan Yuan Daniel Hu/Yanna Yau Gang Shen/Min Huang Warren/Grace/ Saw Ng Daniel Ruan/Ivy Huang George Zhu/Lanfang Qiao 十 一 月 7 14 21 Staff-on-duty: Dili Zhang Andy Zhang Huan Yu Parents-on-duty: Greg (Gang) Sun/Fenyen Chang Hugues St Pierre/Ping Cao Jiangrong Chen/Yujuan Zhou Guanliang Qiau/Haili Zhang Huiming Zhang/Weihong Wang Jianning Zhu/Qinying Gao Haisheng Lu/Rong Wang Jack/Chio Ling Jianqing Hu/Qian Chen Hanli Wang/Ju Zhang Jeff Gao/Quzzna Zhao Jicneng Yang/Wei Su Henry Lebensbaum/n/a Jerry Guo/Lucy Xie Jingang Zhang/Xiaolei Qi Hongwei Shi/Minjie Zhang Jerry Palma/Grace Palma Junqing Ma/Huihong Song Karl Hoover/Jie Zhang- Hongwei Zhu/Xiaoqi Zhang Jian Wen/Judy Hou Hoover CSA Fall 2010 On-duty Assignment 十 二 月 5 12 19 Staff-on-duty: Judy Tang Emily Sperl Dili Zhang Parents-on-duty: Kenric Anderberg/Margaret Mick Verga/Ping Verga San Liang/Feiyan Zhao Anderberg Khia Tung/Aimy Tung Ming -

Chinese Language and Characters

Chinese Language and Characters Pronunciation of Chinese Words Consonants Pinyin WadeGiles Pronunciation Example: Pinyin(WadeGiles) Aspirated: p p’ pin Pao (P’ao) t t’ tip Tao (T’ao) k k’ kilt Kuan (K’uan) ch ch’ ch in, ch urch Chi (Ch’i) q ch’ ch eek Qi (Ch’i) c ts’ bi ts Cang (Ts’ang) Un- b p bin Bao (Pao) aspirated: d t dip Dao (Tao) g k gilt Guan (Kuan) r j wr en Ren (Jen) sh sh sh ore Shang (Shang) si szu Si (Szu) x hs or sh sh oe Xu (Hsu) z ts or tz bi ds Zang (Tsang) zh ch gin Zhong (Chong) zh j jeep Zhong (Jong) zi tzu Zi (Tzu) Vowels - a a father usually Italian e e ei ght values eh eh broth er yi i mach ine, p in Yi (I) i ih sh ir t Zhi (Chih) o soap u goo se ü über Dipthongs ai light ao lou d ei wei ght ia Will ia m ieh Kor ea ou gr ou p ua swa n ueh do er ui sway Hui (Hui) uo Whoah ! Combinations ian ien Tian (Tien) ui wei Wei gh Shui (Shwei) an and ang bun and b ung en and eng wood en and am ong in and ing sin and s ing ong un and ung u as in l oo k Tong (T’ung) you yu Watts, Alan; Tao The Watercourse Way, Pelican Books, 1976 http://acc6.its.brooklyn.cuny.edu/~phalsall/texts/chinlng1.html Tones 1 2 3 4 ā á ă à ē é ĕ È è Ī ī í ĭ ì ō ó ŏ ò ū ú ŭ ù Pinyin (Wade Giles) Meaning Ai Bā (Pa) Eight, see Numbers Bái (Pai) White, plain, unadorned Băi (Pai) One hundred, see Numbers Bāo Envelop Bāo (Pao) Uterus, afterbirth Bēi Sad, Sorrow, melancholy Bĕn Root, origin (Biao and Ben) see Biao Bi Bi (bei) Bian Bi āo Tip, dart, javelin, (Biao and Ben) see Ben Bin Bin Bing Bu Bu Can Cang Cáng (Ts’ang) Hidden, concealed (see Zang) Cháng Intestine Ch ōng (Ch’ung) Surging Ch ōng (Ch’ung) Rushing Chóu Worry Cóng Follow, accord with Dăn (Tan) Niche or shrine Dăn (Tan) Gall Bladder Dān (Tan) Red Cinnabar Dào (Tao) The Way Dì (Ti) The Earth, i.e. -

Performing Chinese Contemporary Art Song

Performing Chinese Contemporary Art Song: A Portfolio of Recordings and Exegesis Qing (Lily) Chang Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Elder Conservatorium of Music Faculty of Arts The University of Adelaide July 2017 Table of contents Abstract Declaration Acknowledgements List of tables and figures Part A: Sound recordings Contents of CD 1 Contents of CD 2 Contents of CD 3 Contents of CD 4 Part B: Exegesis Introduction Chapter 1 Historical context 1.1 History of Chinese art song 1.2 Definitions of Chinese contemporary art song Chapter 2 Performing Chinese contemporary art song 2.1 Singing Chinese contemporary art song 2.2 Vocal techniques for performing Chinese contemporary art song 2.3 Various vocal styles for performing Chinese contemporary art song 2.4 Techniques for staging presentations of Chinese contemporary art song i Chapter 3 Exploring how to interpret ornamentations 3.1 Types of frequently used ornaments and their use in Chinese contemporary art song 3.2 How to use ornamentation to match the four tones of Chinese pronunciation Chapter 4 Four case studies 4.1 The Hunchback of Notre Dame by Shang Deyi 4.2 I Love This Land by Lu Zaiyi 4.3 Lullaby by Shi Guangnan 4.4 Autumn, Pamir, How Beautiful My Hometown Is! by Zheng Qiufeng Conclusion References Appendices Appendix A: Romanized Chinese and English translations of 56 Chinese contemporary art songs Appendix B: Text of commentary for 56 Chinese contemporary art songs Appendix C: Performing Chinese contemporary art song: Scores of repertoire for examination Appendix D: University of Adelaide Ethics Approval Number H-2014-184 ii NOTE: 4 CDs containing 'Recorded Performances' are included with the print copy of the thesis held in the University of Adelaide Library.