BURMA Cornell University Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JSS 046 2B Luce Earlysyamin

THE EAFk v SYAM IN Bi.JRrviAjS HIS16RV by G. H. Luce 1 Not long ago, I was asked to give an opinion about a pro posal to write the history of the Shans. The proposal came from a Shan scholar for whom I have great respect, and who was as well fitted as any Shan I know to do the work. He planned to assemble copies of all the Shan State Chronicles extant; to glean all references to the Shan States in Burmese Chronicles; and finally to collect source materiu.ls in English. · Such, in brief, was the plan. I had to point out that it omitted what, for the older periods at least, were the most important sources of all: the original Old 'l'h ai inscriptions of the north, the number of which, if those from East Bm·ma, North Siam and Laos, are included, may well exceed a hundred; 1 and the elated contem porary reco1·cls in Chinese, from the 13th century onwards. I do not know if these sources have been adequately tapped in Siam. · They certainly have not in Burma. And since the earlier period, say 1.250 to 1450 A.D., is the time of the m~'tSS movements of the Dai2 southward from Western Yunnan, radiating all over Fmther India and beyond, the subject is one, I think, that concerns Siam no less than Burma. I am a' poor scholar of 'l'hai; so I shall confine myself here to Chinese and Burmese sources. The Chinese ones are mainly the dynastic histories of the Mongols in China (the Yuan-shih ), and the his-' tory of the earlier half of the Ming dynasty (the Ming-shih ). -

A Case Study for Development of Tradition and Culture of Myanmar People Based on Some Myanmar Traditional Festivals

A Case Study for Development of Tradition and Culture of Myanmar People Based on some Myanmar Traditional Festivals Aye Pa Pa Myo* [email protected] Assistant Lecturer, Department of English, Yangon University of Education, Myanmar Abstract It is generally said that Myanmar is a beautiful country situated on the land of Southeast Asia and it is also a land of traditional festivals which has the collection of tradition and culture. This paper has an attempt to observe the development of tradition and culture of Myanmar People based on some Myanmar Traditional Festivals. The research was done with analytical approach. It took three months. self-observation, questionnaires, taking photos, and interviewing were used as the research tools. Data were analyzed with the qualitative and quantitative methods. In accordance with the findings, it can be clearly seen that the majority of Myanmar enjoy maintaining and admiring their tradition and culture, assisting others as much as they can, hospitalizing the others, particularly, foreigners. Their inspiration can influence the tourists, as well as Myanmar Traditional Festivals can reveal the lovely and beautiful Myanmar Tradition and Culture. Therefore, the Republic of the Union of Myanmar can be called the Land of Culture to the great extent. In brief, the findings from the research will support to further research related to observing dynamic development of Aspects of Myanmar. Key Terms- tradition and culture Introduction Our Country, the Republic of the Union of Myanmar situated on the Indochina Peninsula in South East Asia is well-known as “the Golden Land” because of its glittering pagodas, vast tract of timber forests, huge mineral resources, wonderful historical sites and monuments and the hospitality of Myanmar People. -

Of the Story

OUR SIDE OF THE STORY VOICES t Black Hawk College OUR SIDE OF THE STORY VOICES t Black Hawk College Fall 2014 www.bhc.edu English as a Second Language Program TABLE OF CONTENTS InterestingInteresting Facts Facts aboutaboutTABLE My My Ethnic Ethnic Identity Identity OF By ByElmiraCONTENTS Elmira Shakhbazova Shakhbazova ....................................... ................................ ... 2 2 The The Holidays inin Vietnam By DuocDuoc HoangHoang Nguyen Nguyen .................................................................. .............................................................. 5 5 Ways of Celebrating Thanksgiving in Rwanda By Emmanuel Hakizimana .............................. 8 WaysInteresting of Celebrating Facts about Thanksgiving My Ethnic Identity in Rwanda By Elmira By Emmanuel Shakhbazova Hakizimana ................................ ........................... 28 Young Initiation in North Togo By Amy Nicole Agboh ........................................................... 10 Young Initiation in North Togo By Amy Nicole Agboh ......................................................... 10 TheBurmese Holidays Calendar in Vietnam and Traditions By Duoc HoangBy George Nguyen Htain ................................ ........................................................................................... 513 BurmeseWaysNaming of inCelebrating Calendar Ewe By Komalan and Thanksgiving Traditions Novissi Byin Gavon RwandaGeorge ........................................................................... HtainBy Emmanuel ............................... -

Shwebo District Volume A

BURMA GAZETTEER SHWEBO DISTRLCT VOLUME A COMPILED BY Ma. A. WILLIAMSON, I.C.S. SETTLEMENT OFFICER, RANGOON SUPERINTENDENT, GOVERMENT PRINTING AND STATIONERY, RANGOON. LIST OF AGENTS FROM WHOM GOVERNMENT OF BURMA PUBLICATIONS ARE AVAILABLE IN BURMA 1. CITY BOOK CLUB, 98, Phayre Street, Rangoon. 2. PROPRIETOR, THU-DHAMA-WADI PRESS, 55-56, Tees Kai Maung Khine Street, Rangoon. 3. PROPRIETOR, BURMA NEWS AGENCY, 135, Anawrahta Street, Rangoon. 4. MANAGER, UNION PUBLISHING HOUSE, 94, "C" Block, Bogyoke Market, Rangoon. 5. THE SECRETARY, PEOPLE'S LITERATURE COMMITTEE AND HOUSE, 546, Merchant Street, Rangoon. 6. THE BURMA TRANSLATION SOCIETY, 520, Merchant Street, Rangoon. 7. MESSRS. K. BIN HOON & SONS, Nyaunglebin, Pegu District. 8. U Lu GALE, GOVERNMENT LAW BOOK AGENT, 34th Road, Nyaungzindan Quarter, Mandalay. 9. THE NATIONAL BOOK DEPOT AND STATIONERY SUPPLY HOUSE, North Godown, Zegyo, Mandalay. 10. KNOWLEDGE BOOK HOUSE, 130, Bogyoke Street, Rangoon. 11. AVA HOUSE, 232, Sule Pagoda Road, Rangoon. 12. S.K. DEY, BOOK SUPPLIER & NEWS AGENTS (In Strand Hotel), 92, Strand Road, Rangoon. 13. AGAWALL BOOKSHOP, Lanmadaw, Myitkyina. 14- SHWE OU DAUNG STORES, BOOK SELLERS & STATIONERS, No. 267, South Bogyoke Road, Moulmein. 15. U AUNG TIN, YOUTH STATIONERY STORES, Main Road, Thaton. 16. U MAUNG GYI, AUNG BROTHER BOOK STALL, Minmu Road, Monywa. 17. SHWEHINTHA STONES, Bogyoke Road, Lashio, N.S.S. 18. L. C. BARUA, PROPRIETOR, NATIONAL STORES, No. 16-17, Zegyaung Road, Bassein. 19. DAW AYE KYI, No. 42-44 (in Bazaar) Book Stall, Maungmya. 20. DOBAMA U THEIN, PROPRIETOR, DOBAMA BOOK STALL, No. 6, Bogyoke Street, Henzada. 21. SMART AND MOOKRRDUM, NO. 221, Sule Pagoda Road, Rangoon. -

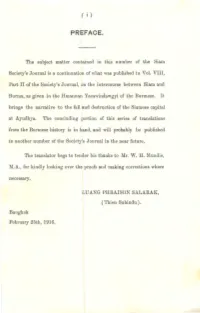

Intercourse Between Burma and Siam As Recorded In

( i ) PREFACE. The subject matter contained in this number of the Siam Society's Journal is a continuation of what was published in Vol. VIII, Part II of the Society's Jon mal, on the intercourse between Siam and Burma, as given in the Hmannan Yazawindawgyi of the Burmese. It brings the narrative to the fall and destruction of the Siamese capital at .A.yudhya. The concluding portion of this series of translations from the Burmese history is in hand, and will probably be published in another number of the Society's Journal in the near future. 1'he translator begs to tender his thanks to Mr. W. H. :Mundie, M.A., for kindly looking over the proofs and making corrections where necessary. LU .A.NG PHR.A.ISON SALA.RA.K, ( Thien Subindu). Bangkok February 25th, 1916. ( ii ) CONTENTS. Paper. Page. I. Rise of Alaung Mintayagyi, his conquest of Hanthawadi, and his invasion of Siam l Sir Arthur P. Phayre's account of the same 14 II. Accession of Alaung Mintayagyi's eldest son, Prince of Dabayin, to the throne and his death. Succession to the throne of Alaung Mintayagyi's second son, Prince of Myedu, and his invasion of Siam. 17 List of Kings of Ayudhya as given in the Hmannan history 57 Sir Arthur P. Phayre's account of the same 62 ( iii ) CORRIGENDA AND ADDENDA. Page 2, line 6 of last para, for 'Kyaing-ton' read ' Kyaing-tOn.' 4, first. line of last pam, the first word in the bracket should " be ' Siri.' 4, last line of last para, for ' Kyankmyaung' read ' Kyankm " yaung.' 4, foot-note 1., delete ' I. -

Bur a and the Burmese

Bur a and the Burmese A Historical Perspective by Eric S. Casino ~ited by Bjorn Schelander with illustrations by Ann Hsu Partially funcled by the U.S. Department of Education Center for Southeast Asian Studies School of Hawaiian, Asian and Pacific Studies University of Hawai'i July 1997 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations i Preface ii Chapter One LAND AND PEOPLE 1 Chapter Two FROM PAST TO PRESENT 17 Chapter Three RELIGION 49 Chapter Four LIFE AND CULTURE 65 Chapter Five BURMA AFTER INDEPENDENCE 85 Key to Exercises 104 BASIC REFERENCES 114 List of Illustrations Burmese Fishermen 8 Temples of Pagan 19 Shwedagon Pagoda 57 Chinthes (mythical creatures) 71 Burmese Ox Cart 78 Fisherman in Northern Burma 95 i PREFACE fu 1989, following the rise to power of the new regime, the SLORC (State Law and Order Restoration Council), the official name of the Union of Burma was changed to Union of Myanmar. Many place names were either given new spellings to correct British mistransliterations or replaced by their pre-colonial era names. For example Pagan was replaced by Bagan, Rangoon by Yangon, and Maymyo by Pyin 00 Lwin. However, these new names are not widely used outside (or, for some, inside) the country, and most recent literature has retained the old names and spellings. Hence, to avoid confusion, the old names and spellings will also be retained in this text (including the terms "Burma," "Burman," and "Burmese"). It should be noted that specialists on Burma make an important distinction between "Burman" and "Burmese. II The term Burmese refers to all the people who are citizens of the Union of Burma (Myanmar). -

Waso - June/July

BBBuuuddddddhhhiiisssttt RRRiiitttuuuaaalllsss IIInnn TTThhheee GGGooollldddeeennn lllaaannnddd ooofff MMMyyyaaannnmmmaaarrr The Golden land of Myanmar And Festive Loving People BBBuuuddddddhhhiiisssttt RRRiiitttuuuaaalllsss IIInnn TTThhheee GGGooollldddeeennn lllaaannnddd ooofff MMMyyyaaannnmmmaaarrr PREFACE Many of the Buddhist rituals that people have adopted in various parts of the country across the Golden land are hidden in legends and folks tales. It is very hard for the young’s and olds to comprehend the background of the origination of the legends, local rituals and tradition. This book is compiled and put in one place, most of the major festivals that are current and celebrated to this day in Myanmar. Compiled for the serene Joys and the emotions of the pious and the tradition of the folks tales of the Golden land. 1. Tagu - March/April 2. Kason - April/May 3. Nayon - May/June 4. Waso - June/July 5. Wagaung - July/August 6. Tawtalin- August/September 7. Thadingyut- September/October 8. Tazaungmon – October/November 9. Nadaw - November/December 10. Pyatho - December/January 11.Tabodwe - January/February 12. Tabaung - February/March Page 2 of 47 A Gift of Dhamma Maung Paw, California2 Introduction: To Myanmar’s, it is a tradition of its people to have a fondness for theatre and festivals. Most festivals are called “pwe” in Myanmar; and are related to religion and most often, they are carried out under the patronage of a pagoda or a pagoda trustee committee. Long time ago, most of the famous pagodas in Myanmar had paya-pwes (pagoda-festivals) during winter and most are celebrated in the month of Tabaung (March). Pagoda festivals are literally religious and festive affairs. -

Burmese Arakan Calendars

T HE ME E A RA KA N E S E C ALE N D R BUR S A S . B U RM ESE A RAKAN CALE N D ARS BY . 1 . A . I C 3 x . M B IRW N , D CIV IL S E R V ICE I N IAN . R angoon PRIN T E D HANT HAWAD DY I \VO R KS AT T H E PR NTI N G , 6 S U L E G A R OAD . 4 , PA O D PR E FAC E . IN 1 0 1 ublished 9 I p The B urmese Calendar . It was written in Ireland , and in the preface I admitted that I had not had access to the best sources of . information I can claim that the book was not inaccurate , but it was i n . Pon n a s complete I have since made the acq uaintance of the chief in M andalay , and have learned a good deal more on the subject of the calendar , chiefly U Wiza a from y of Mandalay and Saya Maung M aung of Kemmendine , to whom my acknowledgments are due . I therefore contemplated issuing a second edition , but when I applied myself to the task of revision I found it was desirable re- to write a good deal of the book , and to enlarge its scope by including the Arakanese Calendar . The title of the book is therefore changed . My object has been to make the book intelligible and useful to both E uropeans and Burmans . This must be my excuse if some paragraphs seem to one class or another of readers to enter too much into elementary details . -

The Burmese & Arakanese Calendars

IE BURMESE AND ARAKANESE CALENDARS. WM A. M. B. mWlK 'r>- THE BURMESE & ARAKANESE CALENDARS. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/burmesearakaneseOOirwiiala THE Burmese & Arakanese Calendars BY A. M. B. IRWIN, c. S.I.. INDIAN CIVIL SERVICE. Ranaoon : PRINTED AT THE HANTHAWADDY PRINTING WORKS, 46, SuLE Pagoda Road. 1909. PREFACE. In 1901 I published "The Burmese Calendar." It was written in Ireland, and in the preface I admitted that I had not had access to the best sources of information. I can claim that the book was not inaccurate, but it was in- complete. I have since made the acquaintance of the chief Ponnas in Mandalay, and have learned a good deal more on the subject of the calendar, chiefly from U Wizaya of Mandalay and Saya Maung Maung of Kemmendine, to whom my acknowledgments are due. I therefore contemplated issuing a second edition, but when I applied myself to the task of revision I found it was desirable to re-write a good deal of the book, and to enlarge its scope by including the Arakanese Calendar. The title of the book is therefore changed. My object has been to make the book intelligible and useful to both Europeans and Burmans. This must be my excuse if some paragraphs seem to one class or another of readers to enter too much into elementary details. I have endeavoured firstly to describe the Burmese and Arakanese Calendars as they are. Secondly, I have shown that an erroneous estimate of the length of the year has introduced errors which have defeated the intentions of the designers of the calendar, and I have made suggestions for reform. -

A Festival Lover's Guide to Myanmar

A FESTIVAL LOVER’S GUIDE TO MYANMAR 1 1 2 3 4 5 TABLE OF CONTENT 6 7 8 9 10 11 2 KACHIN MANAW The New Year celebration of the Kachin people. It is a joint festivity FESTIVAL of the new year, battle victories, the ethnic groups’ reunion, and a (NEW YEAR long-standing tradition. Manaw poles are erected, and men and FESTIVAL) women dance around them. This festival is one of the most - EARLY JANUARY - delightful and popular festivals in Myanmar. 1 ANANDA PAGODA FESTIVAL (BAGAN) - MID JANUARY- You can witness the Buddhist rituals and ceremonies of social gatherings. It is also the best occasion to enjoy local home-cooked food. So, be a part of the festivals of Myanmar to know of their culture and relish the local cuisine. KOGYIKYAW 2 SPIRIT FESTIVAL - FEBRUARY- This festival takes place in Magwe Division for 8 days. Ko Gyi Kyaw Nat is a happy and joyous spirit who loves to drink and gamble. Nat worshippers who also worship Ko Gyi Kyaw Nat would provide offerings like food, drinks and money. Locals who are celebrating the spirit also drink alcoholic beverages and eat the spirit’s favourite delicacies. 3 HTAMANE FESTIVAL (ON THE DAY OF THE FULL MOON) - FEBRUARY - Also known as the Glutinous Rice Festival, Htamane is celebrat- ed throughout the country in February. People of Myanmar celebrate the Htamane Festival by cooking glutinous rice together and participate in a competition to see who can make the best glutinous rice. Besides enjoying the demonstrations and cooking competitions involving the locals, tourists can sit together with them, enjoy the glutinous rice and exchange small talk. -

Witness to the Gospel Among Burmese Buddhists Today

This material has been provided by Asbury Theological Seminary in good faith of following ethical procedures in its production and end use. The Copyright law of the united States (title 17, United States code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyright material. Under certain condition specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to finish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specific conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. By using this material, you are consenting to abide by this copyright policy. Any duplication, reproduction, or modification of this material without express written consent from Asbury Theological Seminary and/or the original publisher is prohibited. Contact B.L. Fisher Library Asbury Theological Seminary 204 N. Lexington Ave. Wilmore, KY 40390 B.L. Fisher Library’s Digital Content place.asburyseminary.edu Asbury Theological Seminary 205 North Lexington Avenue 800.2ASBURY Wilmore, Kentucky 40390 asburyseminary.edu RECLAIMING THE ZAYAT MINISTRY: WITNESS TO THE GOSPEL AMONG BURMESE BUDDHISTS MYANMAR by Lazarus Fish A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Missiology E. Stanley Jones School of World Mission and Evangelism Asbury Theological Seminary July 2002 DISSERTATION APPROVAL SHEET This dissertation, entitled RECLAIMING THE ZAYAT MINISTRY: WITNESS TO THE GOSPEL AMONG BURMESE BUDDHISTS IN MYANMAR written by Lazarus Fish and submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Missiology has been read and approved by the undersigned members ofthe Faculty of the E. -

The Maniyadanabon of Shin Sandalinka

THE MANIYADANABON 0 F S H I N S A N D A L I N K A THE CORNELL UNIVERSITY SOUTHEAST ASIA PROGRAM The Southeast Asia Program was organized at Cornell University in the Department of Far Eastern Studies in 1950. It is a teaching and research program of interdisciplinary studies in the humanities, social sciences, and some natural sciences. It deals with Southeast Asia as a region, and with the individual countries of the area: Brunei, Burma, Indonesia, Kampuchea, Laos, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam. The activities of the Program are carried on both at Cornell and in Southeast Asia. They include an undergraduate and graduate curriculum at Cornell which provides instruction by specialists in Southeast Asian cultural history and present-day affairs and offers intensive training in each of the major languages of the area. The Program. sponsors group research projects on Thailand, on Indonesia, on the Philippines, and on linguistic studies of the languages of the area. At the same time, individual staff and students of the Program have done field research in every Southeast Asian country. A list of publications relating to Southeast Asia which may be obtained on prepaid order directly from the Program is given at the end of this volume. Information on Program staff, fellowships, requirements for degrees, and current course offerings will be found in an Announcement of the Department of Asian Studies, obtainable from the Director, Southeast Asia Program, 120 Uris Hall, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853. i i T H E M A N I Y A D A N A B O N 0 F S H I N S A N D A L I N K A Translated by L.