The Truth, but Not the Whole Truth. Memories of Roundhay School, 1950-1957

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Land Train at Roundhay Pk App A.Pdf

Parks & Countryside OS Mapref = SE3337 Scale Roundhay Land Train Route 0 80 160 240 m I E E E 4 2 S U th T a o V C P T t S F 3 E 1 K N A R T L Nursery H A A S P N T K 6 P E a 5 1 N th C E E A 2 2 1 h B 8 U 6 t 9 C Stonecroft a t 3 2 N o 8 S P 9 E 1 30 9 1 E 2 1 V 27 R a A Club 1 2 10 C Y 9 4 3 R 1 El Sub W Key U Sta E The Cottage I B V S 32 E K 34 R T 3 F 6 1 A Garage A 33 P 1 H 2 3 4 3 5 S T 2 5 37 R 2 U 0 O 2 PARK VILLAS 2 2 3 C 2 8 4 40 37 The E 2 4 7 t 4 9 7 o Coach L 2 48 L Posts House I 3 Path V 9 Upper Lake 41 D 43 h O Pat P O AR Pond Fountain FB 127.1m 2 K V W 128.9m 5 ILL Ram Wood to AS Tropical World 36 9 1 o t 4 Sunday Robinwood 1 th a 1 White House 3 P 3 School Court 1 h t Waterfall to t a o 2 P 1 2 4 2 2 1 P 1 1 o A t R ta 1 S K b y h V u The Lodge a c S 8 FB r D IL l h u 9 E d L Waterfall h O A h n FB t u C S P a O a P o d 1 to th R e 6 W 4 2 G s m 1 N ' r a w o El Sub Sta R r f 6 e Fernwood 7 d Fn e to r 12 E 4 e d R n F 2 n Court d V A e 0 5 New t t ie 4 i 2 1 5 S n w 3 Rose U Bowling Green 1 C BM 128.38m 5 2 o Garden P ll 1 u ark Landing Stage Waterfa 0 C 1 ot Car 10 1 rt tages FB 8 Park 7 1 6 1 9 Pavilion Ramwood 7 D Fn 1 a F ERN 1 WO Pond OD 8 MANSION LANE 1 6 2 a 1 4 1 1 127.4m b Posts 7 1 127.7m 5 1 3 28 1 LB BM 125.43m to El Sub Sta 120.4m 25 3 127.1m ION LANE 2 1 26 0 MANS to BM 125.07m 3 27 a 128.9m Mansion House 95 Pond 4 7 D The to A 24 Roundhay Fox O 123.1m Rose Cottage R (PH) 24 K 3 Shelter R Mansion 30 28 A Cottage Mansion House 12 P 1 6 D 0 4 to 95 L 6 O alk w W 115.8m to 3 Ne 34 1 LB Leeds Golf Course Post -

The Pelican Record Corpus Christi College Vol

The Pelican Record Corpus Christi College Vol. LV December 2019 The Pelican Record The President’s Report 4 Features 10 Ruskin’s Vision by David Russell 10 A Brief History of Women’s Arrival at Corpus by Harriet Patrick 18 Hugh Oldham: “Principal Benefactor of This College” by Thomas Charles-Edwards 26 The Building Accounts of Corpus Christi College, Oxford, 1517–18 by Barry Collett 34 The Crew That Made Corpus Head of the River by Sarah Salter 40 Richard Fox, Bishop of Durham by Michael Stansfield 47 Book Reviews 52 The Renaissance Reform of the Book and Britain: The English Quattrocento by David Rundle; reviewed by Rod Thomson 52 Anglican Women Novelists: From Charlotte Brontë to P.D. James, edited by Judith Maltby and Alison Shell; reviewed by Emily Rutherford 53 In Search of Isaiah Berlin: A Literary Adventure by Henry Hardy; reviewed by Johnny Lyons 55 News of Corpuscles 59 News of Old Members 59 An Older Torpid by Andrew Fowler 61 Rediscovering Horace by Arthur Sanderson 62 Under Milk Wood in Valletta: A Touch of Corpus in Malta by Richard Carwardine 63 Deaths 66 Obituaries: Al Alvarez, Michael Harlock, Nicholas Horsfall, George Richardson, Gregory Wilsdon, Hal Wilson 67-77 The Record 78 The Chaplain’s Report 78 The Library 80 Acquisitions and Gifts to the Library 84 The College Archives 90 The Junior Common Room 92 The Middle Common Room 94 Expanding Horizons Scholarships 96 Sharpston Travel Grant Report by Francesca Parkes 100 The Chapel Choir 104 Clubs and Societies 110 The Fellows 122 Scholarships and Prizes 2018–2019 134 Graduate -

School and College (Key Stage 5)

School and College (Key Stage 5) Performance Tables 2010 oth an West Yorshre FE12 Introduction These tables provide information on the outh and West Yorkshire achievement and attainment of students of sixth-form age in local secondary schools and FE1 further education sector colleges. They also show how these results compare with other Local Authorities covered: schools and colleges in the area and in England Barnsley as a whole. radford The tables list, in alphabetical order and sub- divided by the local authority (LA), the further Calderdale education sector colleges, state funded Doncaster secondary schools and independent schools in the regional area with students of sixth-form irklees age. Special schools that have chosen to be Leeds included are also listed, and a inal section lists any sixth-form centres or consortia that operate otherham in the area. Sheield The Performance Tables website www. Wakeield education.gov.uk/performancetables enables you to sort schools and colleges in ran order under each performance indicator to search for types of schools and download underlying data. Each entry gives information about the attainment of students at the end of study in general and applied A and AS level examinations and equivalent level 3 qualiication (otherwise referred to as the end of ‘Key Stage 5’). The information in these tables only provides part of the picture of the work done in schools and colleges. For example, colleges often provide for a wider range of student needs and include adults as well as young people Local authorities, through their Connexions among their students. The tables should be services, Connexions Direct and Directgov considered alongside other important sources Young People websites will also be an important of information such as Ofsted reports and school source of information and advice for young and college prospectuses. -

Leeds Secondary Admission Policy for September 2021 to July 2022

Leeds Secondary Admission Policy for September 2021 to July 2022 Latest consultation on this policy: 13 December 2019 and 23 January 2020 Policy determined on: 12 February 2020 Policy determined by: Executive Board Admissions policy for Leeds community secondary schools for the academic year September 2021 – July 2022 The Chief Executive makes the offer of a school place at community schools for Year 7 on behalf of Leeds City Council as the admissions authority for those schools. Headteachers or school-based staff are not authorised to offer a child a place for these year groups for September entry. The authority to convey the offer of a place has been delegated to schools for places in other year groups and for entry to Year 7 outside the normal admissions round. This Leeds City Council (Secondary) Admission Policy applies to the schools listed below. The published admission number for each school is also provided for September 2021 entry: School name PAN Allerton Grange School 240 Allerton High School 220 Benton Park School 300 Lawnswood School 270 Roundhay All Through School (Yr7) 210 Children with an education, health and care plan will be admitted to the school named on their plan. Where there are fewer applicants than places available, all applicants will be offered a place. Where there are more applicants than places available, we will offer places to children in the following order of priority. Priority 1 a) Children in public care or fostered under an arrangement made by the local authority or children previously looked after by a Local Authority. (see note 1) b) Pupils without an EHC plan but who have Special Educational Needs that can only be met at a specific school, or with exceptional medical or mobility needs, that can only be met at a specific school. -

Some Oakwood Memories © by John Harrison Do You Remember When

From Oak Leaves, Part 11, Spring 2012 - published by Oakwood and District Historical Society [ODHS] Some Oakwood Memories © by John Harrison Do you remember when Connaught Road (the never-finished road across the fields parallel to Prince's Avenue) was more visible at the Old Park Road end? It started at the bend in Old Park Road just before Roundhay School, where there was a gate (was it a kissing-gate?). Do you remember when the fenced Soldiers' Field had bullocks grazing in it (in the 1950s and perhaps earlier)? They were often at long-off when we played cricket near the junction of Gledhow Lane and Old Park Road, and it was best not to be the bowler or fielder if the ball went into the cowclap. Do you remember July 27th 1949 when Princess Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh motored down Prince's Avenue, past the Oakwood Clock and on down Roundhay Road? Do you remember the occasion in the late 1940s when the government tried unsuccessfully to end sweet rationing? Stocks were inadequate and rationing had to be re-imposed. I remember the empty shelves of the Bee Hive sweet shop (a few doors nearer town than the fish and chip shop). All I could get was a Mars bar. Do you remember the steep sided quarries of the Oakwood area in the post war years (and earlier of course)? I and my friends used to play quite happily at a very young age above the sheer drop of the quarry at the junction of St Margaret's View and Fitzroy Drive. -

2014 Admissions Cycle

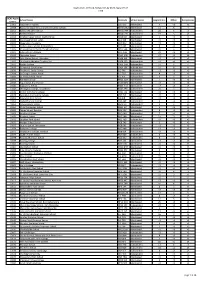

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2014 UCAS Apply School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances Centre 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained 4 <3 <3 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 11 5 4 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 20 5 3 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 19 3 <3 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained 3 <3 <3 10020 Manshead School, Luton LU1 4BB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10022 Queensbury Academy LU6 3BU Maintained <3 <3 <3 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained 4 <3 <3 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 20 6 5 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 21 <3 <3 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 27 13 13 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent <3 <3 <3 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 10 4 4 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 14 8 8 10036 The Marist Senior School SL5 7PS Independent <3 <3 <3 10038 St Georges School, Ascot SL5 7DZ Independent 4 <3 <3 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 6 3 3 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained 7 <3 <3 10043 Ysgol Gyfun Bro Myrddin SA32 8DN Maintained <3 <3 <3 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10045 Wellington College, Crowthorne RG45 7PU Independent 20 6 6 10046 Didcot Sixth Form College OX11 7AJ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10048 Faringdon Community College SN7 7LB Maintained -

Leeds City Council

LEEDS CITY COUNCIL Education Secondary Group Scheme Lawnswood and Roundhay High Schools Project Assessment Submission (Outline Business Case) May 1998 Department of Finance David J.Page, Director 3 Civic Half Leeds LS1 LEER 1JF CITY COUNCIL Cameron McCrea Derek Howell Schools PFI Team tel 0113 2243469 Department for Education and Employment fax 0113 2243426 Sanctuary Buildings Great Smith Street Westminster London SW1P 3BT 14th May 1998 Dear Cameron, Leeds LEA - PFI Project Assessment Submissions Here are the PFI Project Submissions for Leeds, in accordance with the timescale requirements for consideration by the Project Review Group at their May 1998 meeting. There are 3 submissions in all, but as you know the Cardinal Heenan V.A. High School Pathfinder Scheme is being submitted to you directly from the offices of the Project Manager (Povall, Flood and Wilson in Manchester), with the support of the Authority. Your colleague John Kirkpatrick is also aware this will be the case, but I should be grateful if you would confirm that to him upon receipt of this letter. Enclosed therefore are 4 copies (3 bound and I unbound) of the 2 LEA projects as follows: Secondary Group Scheme - Refurbish/rebuild Lawnswood and Roundhay High Schools Primary Group Scheme - Replacement and new build of the 5 schools named in the document I trust these submission fully meet with your requirements and we can anticipate your support in the conLEEDSrations by the PRG in May. If you have any queries please do not hesitate to contact me on the above numbers. Copies of these submissions have been sent to Martin Lipson at the 4P's. -

Congratulations to Everyone Who Collected Their Gold Award on the Afternoon of Tuesday 20 March 2018 in the Queen Anne Room at S

Congratulations to everyone who collected their Gold Award on the afternoon of Tuesday 20th March 2018 in the Queen Anne Room at St James’s Palace. Masha Gordon, Company Director, Grit and Rock, presented the certificates on behalf of HRH The Earl of Wessex. Group 5: North of England Name Licenced Organisation Centre Victoria Banks Herd Farm Activity Centre-Leeds City Council Herd Farm Benjamin Below Bradford Grammar School Bradford Grammar School Niamh Berwick Leeds City Council COMPLETIONS PROJECT Rachel Brown Horsforth School Horsforth School Dominic Clarke Leeds City Council LAZER Thomas Clarkson Prince Henry's Grammar School Prince Henry's Grammar School Joshua Crank Canon Slade School Canon Slade School Nathaniel Davey Bradford Grammar School Bradford Grammar School Cameron Deuchars Leeds City Council LAZER Emma Handley Grammar School at Leeds GSAL Roanna Holmes City of Bradford Metropolitan Borough Youth Service - Shipley Council Alisha Hussain Bradford Grammar School Bradford Grammar School Mehreen Khalil Bradford Grammar School Bradford Grammar School Joshua Lamming Reading Blue Coat School Reading Blue Coat School James Martin Peaty Roundhay School Roundhay School Mohammad Razzaq Hertfordshire County Council Parmiter's School Evangeline Reuben Leeds University Union Leeds University Union DofE Award Society Jessica Rooney Grammar School at Leeds GSAL Millie Sanders Roundhay School Roundhay School Sophia Wakefield Grammar School at Leeds GSAL Abi White City of Bradford Metropolitan Borough Youth Service - Shipley Council Mark -

The Leeds City Council Held at the Civic Hall, Leeds on Friday 20Th May 2005

Proceedings of a Special Meeting of the Leeds City Council held at the Civic Hall, Leeds on Friday 20th May 2005 PRESENT: The Lord Mayor Councillor Christopher Townsley in the Chair WARD WARD ADEL & WHARFEDALE CALVERLEY & FARSLEY Barry John Anderson Andrew Carter John Leslie Carter Amanda Lesley Carter Frank Robinson ALWOODLEY CHAPEL ALLERTON Sharon Hamilton Mohammed Rafique Peter Mervyn Harrand Jane Dowson ARDSLEY & ROBIN HOOD CITY & HUNSLET Karen Renshaw Elizabeth Nash Patrick Davey Lisa Mulherin Mohammed Iqbal ARMLEY CROSSGATES & WHINMOOR Suzi Armitage James McKenna Pauleen Grahame Janet Harper Peter John Gruen BEESTON & HOLBECK FARNLEY & WORTLEY Angela Gabriel David Blackburn Adam Ogilvie Ann Blackburn Claire Nash BRAMLEY & STANNINGLEY GARFORTH & SWILLINGTON Angela Denise Atkinson Andrea Harrison Ted Hanley Mark Russell Phillips Neil Taggart Thomas Murray BURMANTOFTS & RICHMOND HILL GIPTON & HAREHILLS Ralph Pryke Alan Leonard Taylor Richard Brett Javaid Akhtar David Hollingsworth GUISELEY & RAWDON MORLEY NORTH Graham Latty Robert Finnigan Stewart McArdle John Bale Thomas Leadley HAREWOOD MORLEY SOUTH Ann Castle Judith Elliott Terrence Grayshon Gareth Edward Beevers HEADINGLEY OTLEY & YEADON Grahame Peter Kirkland Greg Mulholland Colin Campbell Martin Hamilton Richard Downes HORSFORTH PUDSEY Josephine Patricia Jarosz Brian Cleasby Andrew Barker Mick Coulson HYDE PARK & WOODHOUSE ROTHWELL Donald Michael Wilson Kabeer Hussain Steve Smith Linda Valerie Rhodes-Clayton Mitchell Galdas KILLINGBECK & SEACROFT ROUNDHAY Graham Hyde Michael -

INSPECTION REPORT Roundhay School Technology College Leeds

INSPECTION REPORT Roundhay School Technology College Leeds LEA area: Leeds Unique reference number: 108076 Headteacher: Neil Clephan Lead inspector: Elizabeth Charlesworth Dates of inspection: 11th - 15th October 2004 Inspection number: 269469 Inspection carried out under section 10 of the School Inspections Act 1996 © Crown copyright 2004 This report may be reproduced in whole or in part for non-commercial educational purposes, provided that all extracts quoted are reproduced verbatim without adaptation and on condition that the source and date thereof are stated. Further copies of this report are obtainable from the school. Under the School Inspections Act 1996, the school must provide a copy of this report and/or its summary free of charge to certain categories of people. A charge not exceeding the full cost of reproduction may be made for any other copies supplied. Roundhay School Technology College - 2 INFORMATION ABOUT THE SCHOOL Type of school: Comprehensive School category: Community Age range of pupils: 11-18 Gender of pupils: Mixed Number on roll; 1502 School address: Gledhow Lane Leeds West Yorkshire Postcode: LS8 1ND Telephone number: 0113 393 1200 Fax number: 0113 393 1201 Appropriate authority: Local education authority Name of chair of governors: Gillian Hayward Date of previous inspection: 20/9/1999 CHARACTERISTICS OF THE SCHOOL Roundhay School is a large comprehensive school and specialist technology college with a large sixth form. The school has recently been completely rebuilt and occupies a large site on the north side of the city of Leeds. About 30 per cent of pupils and students come from ethnic minority backgrounds and 20 per cent have English as an additional language, this broad mix reflecting the diversity of Leeds. -

"GLEDHOW SCHOOL - Gledhow Lane 1872 -1959" © by Barbara Barr

From Oak Leaves, Part 1, Spring 2001 - published by Oakwood and District Historical Society [ODHS] "GLEDHOW SCHOOL - Gledhow Lane 1872 -1959" © by Barbara Barr Photo of Gledhow School January 2001 - now Stepping Stones Nursery. The school is situated on the left hand side of a slight bend on Gledhow Lane after leaving Old Park Rd. junction and before Thorn Lane cross- road. A central reservation of grass and large trees furnish the scene, and children would run through the narrow footpath on their way to school. Of course very little traffic was prevalent until after 1945, and the atmosphere was quite peaceful and countrified. Some deliveries were made by horse and cart. Mr. Laycock, the Greengrocer at Oakwood and Mr. Addy, Lidgett Lane farm, in handsome horse and trap with large milk churn aboard, and smaller cream, were regularly to be seen. Opposite the school frontage was the hockey field to Roundhay High School for Girls, later to become the site of the Kerr Mackie Primary, which opened on the 2nd July 1993. The Headmaster of Roundhay Boys' School's house was built directly opposite the little church school (Gledhow School) and a house for the Headmistress was built close to the entrance gate at Thorn Lane junction. The school was built about 1872/3 with money raised by public subscription, following a gift of land to the Diocese of Ripon by a descendant of Jeremiah Dixon of Gledhow Hall - John Dixon. It was intended for the education of the poor in the locality, first regulated by, and belonging to St. -

Roundhay School All-Through Education from 4 to 18 Gledhow Lane, Leeds, West Yorkshire, LS8 1ND

School report Roundhay School All-through education from 4 to 18 Gledhow Lane, Leeds, West Yorkshire, LS8 1ND Inspection dates 20–21 November 2013 Previous inspection: Good 2 Overall effectiveness This inspection: Outstanding 1 Achievement of pupils Outstanding 1 Quality of teaching Outstanding 1 Behaviour and safety of pupils Outstanding 1 Leadership and management Outstanding 1 Summary of key findings for parents and pupils This is an outstanding school. Roundhay School is all about its students. Primary provision is outstanding. Pupils make Staff ensure that each one, regardless of extremely rapid progress, teaching is background or ability, is given every outstanding, resources are first-rate and opportunity to shine. leadership is exceptional. An inspirational headteacher, very strong Support for students with special educational leadership, highly skilled teachers and needs is excellent, enabling them to participate teaching assistants, plus dedicated support well and realise their potential. staff combine to give students a first class The sixth form is outstanding. The quality of education. teaching is high and students make very good Students make rapid progress and academic progress. Facilities are high quality and standards are high. The gap in attainment enrichment opportunities are excellent. between students supported by pupil Staff training is excellent. premium and others is closing at a Governors use their considerable knowledge remarkable rate. and experience to support and challenge Students are taught extremely well and given leaders extremely well. excellent verbal feedback but not all marking is of the highest quality. Student and staff relationships are extremely good. Students’ personal development is exceptional and behaviour is exemplary.