The Roots of Leeds AC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

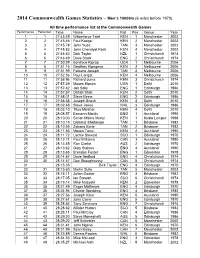

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics – Men's

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics – Men’s 10000m (6 miles before 1970) All time performance list at the Commonwealth Games Performance Performer Time Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 27:45.39 Wilberforce Talel KEN 1 Manchester 2002 2 2 27:45.46 Paul Kosgei KEN 2 Manchester 2002 3 3 27:45.78 John Yuda TAN 3 Manchester 2002 4 4 27:45.83 John Cheruiyot Korir KEN 4 Manchester 2002 5 5 27:46.40 Dick Taylor NZL 1 Christchurch 1974 6 6 27:48.49 Dave Black ENG 2 Christchurch 1974 7 7 27:50.99 Boniface Kiprop UGA 1 Melbourne 2006 8 8 27:51.16 Geoffrey Kipngeno KEN 2 Melbourne 2006 9 9 27:51.99 Fabiano Joseph TAN 3 Melbourne 2006 10 10 27:52.36 Paul Langat KEN 4 Melbourne 2006 11 11 27:56.96 Richard Juma KEN 3 Christchurch 1974 12 12 27:57.39 Moses Kipsiro UGA 1 Delhi 2010 13 13 27:57.42 Jon Solly ENG 1 Edinburgh 1986 14 14 27:57.57 Daniel Salel KEN 2 Delhi 2010 15 15 27:58.01 Steve Binns ENG 2 Edinburgh 1986 16 16 27:58.58 Joseph Birech KEN 3 Delhi 2010 17 17 28:02.48 Steve Jones WAL 3 Edinburgh 1986 18 18 28:03.10 Titus Mbishei KEN 4 Delhi 2010 19 19 28:08.57 Eamonn Martin ENG 1 Auckland 1990 20 20 28:10.00 Simon Maina Munyi KEN 1 Kuala Lumpur 1998 21 21 28:10.15 Gidamis Shahanga TAN 1 Brisbane 1982 22 22 28:10.55 Zakaria Barie TAN 2 Brisbane 1982 23 23 28:11.56 Moses Tanui KEN 2 Auckland 1990 24 24 28:11.72 Lachie Stewart SCO 1 Edinburgh 1970 25 25 28:12.71 Paul Williams CAN 3 Auckland 1990 25 26 28:13.45 Ron Clarke AUS 2 Edinburgh 1970 27 27 28:13.62 Gary Staines ENG 4 Auckland 1990 28 28 28:13.65 Brendan Foster ENG 1 Edmonton 1978 29 29 28:14.67 -

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics–Men's 5000M (3 Mi Before

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics –Men’s 5000m (3 mi before 1970) by K Ken Nakamura All time performance list at the Commonwealth Games Performance Performer Time Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 12:56.41 Augustine Choge KEN 1 Melbourne 2006 2 2 12:58.19 Craig Mottram AUS 2 Melbourne 2006 3 3 13:05.30 Benjamin Limo KEN 3 Melbourne 2006 4 4 13:05.89 Joseph Ebuya KEN 4 Melbourne 2006 5 5 13:12.76 Fabian Joseph TAN 5 Melbourne 2006 6 6 13:13.51 Sammy Kipketer KEN 1 Manchester 2002 7 13:13.57 Benjamin Limo 2 Manchester 2002 8 7 13:14.3 Ben Jipcho KEN 1 Christchurch 1974 9 8 13.14.6 Brendan Foster GBR 2 Christchurch 1974 10 9 13:18.02 Willy Kiptoo Kirui KEN 3 Manchester 2002 11 10 13:19.43 John Mayock ENG 4 Manchester 2002 12 11 13:19.45 Sam Haughian ENG 5 Manchester 2002 13 12 13:22.57 Daniel Komen KEN 1 Kuala Lumpur 1998 14 13 13:22.85 Ian Stewart SCO 1 Edinburgh 1970 15 14 13:23.00 Rob Denmark ENG 1 Victoria 1994 16 15 13:23.04 Henry Rono KEN 1 Edmonton 1978 17 16 13:23.20 Phillimon Hanneck ZIM 2 Victoria 1994 18 17 13:23.34 Ian McCafferty SCO 2 Edinburgh 1970 19 18 13:23.52 Dave Black ENG 3 Christchurch 1974 20 19 13:23.54 John Nuttall ENG 3 Victoria 1994 21 20 13:23.96 Jon Brown ENG 4 Victoria 1994 22 21 13:24.03 Damian Chopa TAN 6 Melbourne 2006 23 22 13:24.07 Philip Mosima KEN 5 Victoria 1994 24 23 13:24.11 Steve Ovett ENG 1 Edinburgh 1986 25 24 13:24.86 Andrew Lloyd AUS 1 Auckland 1990 26 25 13:24.94 John Ngugi KEN 2 Auckland 1990 27 26 13:25.06 Moses Kipsiro UGA 7 Melbourne 2006 28 13:25.21 Craig Mottram 6 Manchester 2002 29 27 13:25.63 -

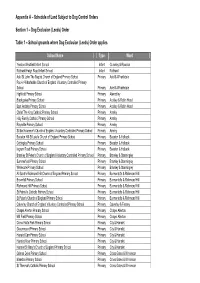

Schedule of Land Subject to Dog Control Orders Section 1

Appendix A – Schedule of Land Subject to Dog Control Orders Section 1 – Dog Exclusion (Leeds) Order Table 1 – School grounds where Dog Exclusion (Leeds) Order applies School Name Type Ward Yeadon Westfield Infant School Infant Guiseley & Rawdon Rothwell Haigh Road Infant School Infant Rothwell Adel St John The Baptist Church of England Primary School Primary Adel & Wharfedale Pool-in-Wharfedale Church of England Voluntary Controlled Primary School Primary Adel & Wharfedale Highfield Primary School Primary Alwoodley Blackgates Primary School Primary Ardsley & Robin Hood East Ardsley Primary School Primary Ardsley & Robin Hood Christ The King Catholic Primary School Primary Armley Holy Family Catholic Primary School Primary Armley Raynville Primary School Primary Armley St Bartholomew's Church of England Voluntary Controlled Primary School Primary Armley Beeston Hill St Luke's Church of England Primary School Primary Beeston & Holbeck Cottingley Primary School Primary Beeston & Holbeck Ingram Road Primary School Primary Beeston & Holbeck Bramley St Peter's Church of England Voluntary Controlled Primary School Primary Bramley & Stanningley Summerfield Primary School Primary Bramley & Stanningley Whitecote Primary School Primary Bramley & Stanningley All Saint's Richmond Hill Church of England Primary School Primary Burmantofts & Richmond Hill Brownhill Primary School Primary Burmantofts & Richmond Hill Richmond Hill Primary School Primary Burmantofts & Richmond Hill St Patrick's Catholic Primary School Primary Burmantofts & Richmond Hill -

INSIDE a Stage Freedom to Love Utd Footy BOOKS

LEEDS 5 e ag p — t rp exce r he tc Ca INDEPENDENT NEWSPAPER Spy • Amazement as Minister visits Leeds `He knows nothing' A fact finding mission to Leeds io,• students Charles Riley and by new Minister for Higher David Shelling recited their Education Robert Jackson. poems against government turned into an acute embarrass- education policy, part of their ment when it became clear that repertoire as the comedy group he was painfully uninformed on 'Codmen Inc'. the country's education situa- The 'alternative' demo was tion. organised by the Students Un- Student leaders were clearly ion to avoid the more orthodox amazed at the ministers lack of method of jeering and egg knowledge. Poly Union presi- throwing . dent Ed Gamble said. "I fear At the University no such for Higher Education with this originality was in evidence. man at the helm. He know no- Near 150 people turned up to thing." the disappointingly small demo LUU general secretary Ger- outside the great Hall, which he maine Varnay was also none visited during the afternoon. too impressed. Nominated by the Exec to meet the minister LULI administration officer and put forward the Unions Austen Earth put the low turn- opposition to reduced govern- out down to the time of year, ment funding. she left the con- "It's very difficult to motivate frontation frustrated. people at this time of year. 'He was so patronising and They're heavily involved in condescending. Predictably he their social lives." he said. didn't listen to a word I said.' Nevertheless the crowd was The day long trip was heavily able to produce an astonishing punctuated by demonstrations volume of noise on the arrival • Robert Jackson MP. -

Men's 100M Diamond Discipline 13.07.2021

Men's 100m Diamond Discipline 13.07.2021 Start list 100m Time: 19:25 Records Lane Athlete Nat NR PB SB 1 Isiah YOUNG USA 9.69 9.89 9.89 WR 9.58 Usain BOLT JAM Olympiastadion, Berlin 16.08.09 2 Chijindu UJAH GBR 9.87 9.96 10.03 AR 9.86 Francis OBIKWELU POR Olympic Stadium, Athina 22.08.04 3André DE GRASSECAN9.849.909.99=AR 9.86 Jimmy VICAUT FRA Paris 04.07.15 =AR 9.86 Jimmy VICAUT FRA Montreuil-sous-Bois 07.06.16 4 Trayvon BROMELL USA 9.69 9.77 9.77 NR 9.87 Linford CHRISTIE GBR Stuttgart 15.08.93 5Fred KERLEYUSA9.699.869.86WJR 9.97 Trayvon BROMELL USA Eugene, OR 13.06.14 6Zharnel HUGHESGBR9.879.9110.06MR 9.78 Tyson GAY USA 13.08.10 7 Michael RODGERS USA 9.69 9.85 10.00 DLR 9.69 Yohan BLAKE JAM Lausanne 23.08.12 8Adam GEMILIGBR9.879.9710.14SB 9.77 Trayvon BROMELL USA Miramar, FL 05.06.21 2021 World Outdoor list Medal Winners Road To The Final 9.77 +1.5 Trayvon BROMELL USA Miramar, FL (USA) 05.06.21 1Ronnie BAKER (USA) 16 9.84 +1.2 Akani SIMBINE RSA Székesfehérvár (HUN) 06.07.21 2019 - IAAF World Ch. in Athletics 2 Akani SIMBINE (RSA) 15 9.85 +1.5 Marvin BRACY USA Miramar, FL (USA) 05.06.21 1. Christian COLEMAN (USA) 9.76 3 Lamont Marcell JACOBS (ITA) 13 9.85 +0.8 Ronnie BAKER USA Eugene, OR (USA) 20.06.21 2. -

The Leeds Scheme for Financing Schools

The Leeds Scheme for Financing Schools Made under Section 48 of the School Standards and Framework Act 1998 School Funding & Initiatives Team Prepared by Education Leeds on behalf of Leeds City Council Leeds Scheme April 2007 LIST OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 The funding framework 1.2 The role of the scheme 1.2.1 Application of the scheme to the City Council and maintained schools 1.3 Publication of the scheme 1.4 Revision of the scheme 1.5 Delegation of powers to the head teacher 1.6 Maintenance of schools 2. FINANCIAL CONTROLS 2.1.1 Application of financial controls to schools 2.1.2 Provision of financial information and reports 2.1.3 Payment of salaries; payment of bills 2.1.4 Control of assets 2.1.5 Accounting policies (including year-end procedures) 2.1.6 Writing off of debts 2.2 Basis of accounting 2.3 Submission of budget plans 2.3.1 Submission of Financial Forecasts 2.4 Best value 2.5 Virement 2.6 Audit: General 2.7 Separate external audits 2.8 Audit of voluntary and private funds 2.9 Register of business interests 2.10 Purchasing, tendering and contracting requirements 2.11 Application of contracts to schools 2.12 Central funds and earmarking 2.13 Spending for the purposes of the school 2.14 Capital spending from budget shares 2.15 Financial Management Standard 2.16 Notice of concern 3. INSTALMENTS OF BUDGET SHARE; BANKING ARRANGEMENTS 3.1 Frequency of instalments 3.2 Proportion of budget share payable at each instalment 3.3 Interest clawback 3.3.1 Interest on late budget share payments 3.4 Budget shares for closing schools 3.5 Bank and building society accounts 3.5.1 Restrictions on accounts 3.6 Borrowing by schools 3.7 Other provisions 4. -

It Was 8 Years After the War…

Cliff Jones Critical Professional Learning TOFFS AND TOUGHS OF THE TRACK News of the death of Roger Bannister reminded me of one of Britain’s greatest athletes, Alf Tupper. A welder by trade Alf would often have to work all night to finish a job. Then he would grab his kit, especially his spikes, and hitch a lift on the back of a lorry to get to a meeting. Before entering the stadium he would buy fish and chips, always wrapped in newspaper, often eating them by the track much to the disgust of some official in neatly pressed trousers, a double-breasted blazer and a panama hat. The race was then between the tough and the toffs. The ‘guttersnipe’ had to endure snobbish remarks and attempts to exclude him from membership of his local Harriers but, overcoming all adversity, he would cross the line first exclaiming, “I’VE RUN ‘EM! I’VE RUN ‘EM ALL”. We can be sure that all of this is true because it was recorded in both the Rover and the Victor. Back in 1954 when Bannister ran the first official sub four-minute mile we were one year into the New Elizabethan Age. The year before had seen the Stanley Mathews Cup Final, the first ascent of Everest and, of course, the Coronation. The meeting between Oxford University and the Amateur Athletic Association was filmed. The pacemakers were Christopher Brasher (he did the first half mile) and Chris Chataway (he did the next lap). It was a great and well-planned event. Both Bannister and his pacemakers went on to become very famous and established figures. -

Council Tax 2021/22

Report author: Victoria Bradshaw Tel: 37 88540 Report of the Chief Officer – Financial Services Report to Council Date: 24th February 2021 Subject: Council Tax 2021/22 Are specific electoral wards affected? Yes No If yes, name(s) of ward(s): Has consultation been carried out? Yes No Are there implications for equality and diversity and cohesion and Yes No integration? Will the decision be open for call-in? Yes No Does the report contain confidential or exempt information? Yes No If relevant, access to information procedure rule number: Appendix number: Summary 1. Main issues • Section 30 of the Local Government Act 1992 imposes on the City Council a duty to set council taxes within its area. This report sets out the background to the calculations, the various steps in the process and the proposed council taxes for 2021/ 22 including the precepts issued by the Police and Crime Commissioner for West Yorkshire, the West Yorkshire Fire & Rescue Authority and the parish and town councils within the Leeds area. • It is proposed that Leeds City Council’s element of the Band D council tax charge be increased by 4.99% to £1,521.29, an increase of 1.99% to the Leeds element plus a 3% increase for the Adult Social Care precept. 2. Best Council Plan Implications (click here for the latest version of the Best Council Plan) • The Best Council Plan is the Council’s strategic plan which sets out its ambitions, outcomes and priorities for the City of Leeds and the Local Authority. • The council tax recommendations detailed in this report have been developed to ensure that appropriate financial resources are provided to support Council policies and the Best Council Plan, as set out in the 2021/22 Revenue Budget and Council Tax report. -

Cricket, Football & Sporting Memorabilia 5Th, 6Th and 7Th March

knights Cricket, Football & Sporting Memorabilia 5th, 6th and 7th March 2021 Online live auction Friday 5th March 10.30am Cricket Memorabilia Saturday 6th March 10.30am Cricket Photographs, Scorecards, Wisdens and Cricket Books Sunday 7th March 10.30am Football & Sporting Memorabilia Next auction 10th & 11th July 2021 Entries invited A buyer’s premium of 20% (plus VAT at 20%) of the hammer price is Online bidding payable by the buyers of all lots. Knights Sporting Limited are delighted to offer an online bidding facility. Cheques to be made payable to “Knight’s Sporting Limited”. Bid on lots and buy online from anywhere in the world at the click of a Credit cards and debit accepted. mouse with the-saleroom.com’s Live Auction service. For full terms and conditions see overleaf. Full details of this service can be found at www.the-saleroom.com. Commission bids are welcomed and should be sent to: Knight’s Sporting Ltd, Cuckoo Cottage, Town Green, Alby, In completing the bidder registration on www.the-saleroom.com and Norwich NR11 7PR providing your credit card details and unless alternative arrangements Office: 01263 768488 are agreed with Knights Sporting Limited you authorise Knights Mobile: 07885 515333 Sporting Limited, if they so wish, to charge the credit card given in part Email bids to [email protected] or full payment, including all fees, for items successfully purchased in the auction via the-saleroom.com, and confirm that you are authorised Please note: All commission bids to be received no later than 6pm to provide these credit card details to Knights Sporting Limited through on the day prior to the auction of the lots you are bidding on. -

Carlton Hill LM

Friends Meeting House, Carlton Hill 188 Woodhouse Lane, LS2 9DX National Grid Reference: SE 29419 34965 Statement of Significance A modest meeting house built in 1987 that provides interconnecting spaces which create flexible, spacious and well-planned rooms which can be used by both the Quakers and community groups. The meeting house has low architectural interest and low heritage value. Evidential value The current meeting house is a modern building with low evidential value. However, it was built on the site of an earlier building dating from the nineteenth century, and following this a tram shed. The site has medium evidential value for the potential to derive information relating to the evolution of the site. Historical value The meeting house has low historical significance as a relatively recent building, however, Woodhouse Lane provides a local context for the history of Quakers in the area from 1868. Aesthetic value This modern building has medium aesthetic value and makes a neutral contribution to the street scene. Communal value The meeting house was built for Quaker use and is also a valued community resource. The building is used by a number of local groups and visitors. Overall the building has high communal value. Part 1: Core data 1.1 Area Meeting: Leeds 1.2 Property Registration Number: 0004210 1.3 Owner: Area Meeting 1.4 Local Planning Authority: Leeds City Council 1.5 Historic England locality: Yorkshire and the Humber 1.6 Civil parish: Leeds 1.7 Listed status: Not listed 1.8 NHLE: Not applicable 1.9 Conservation Area: No 1.10 Scheduled Ancient Monument: No 1.11 Heritage at Risk: No 1.12 Date(s): 1987 1.13 Architect (s): Michael Sykes 1.14 Date of visit: 15 March 2016 1.15 Name of report author: Emma Neil 1.16 Name of contact(s) made on site: Lea Keeble 1.17 Associated buildings and sites: Detached burial ground at Adel NGR SE 26414 39353 1.18 Attached burial ground: No 1.19 Information sources: David M. -

Todos Los Medallistas De Los Campeonatos De Europa

TODOS LOS MEDALLISTAS DE LOS CAMPEONATOS DE EUROPA HOMBRES 100 m ORO PLATA BRONCE Viento 1934 Christiaan Berger NED 10.6 Erich Borchmeyer GER 10.7 József Sir HUN 10.7 1938 Martinus Osendarp NED 10.5 Orazio Mariani ITA 10.6 Lennart Strandberg SWE 10.6 1946 Jack Archer GBR 10.6 Håkon Tranberg NOR 10.7 Carlo Monti ITA 10.8 1950 Étienne Bally FRA 10.7 Franco Leccese ITA 10.7 Vladimir Sukharev URS 10.7 0.7 1954 Heinz Fütterer FRG 10.5 René Bonino FRA 10.6 George Ellis GBR 10.7 1958 Armin Hary FRG 10.3 Manfred Germar FRG 10.4 Peter Radford GBR 10.4 1.5 1962 Claude Piquemal FRA 10.4 Jocelyn Delecour FRA 10.4 Peter Gamper FRG 10.4 -0.6 1966 Wieslaw Maniak POL 10.60 Roger Bambuck FRA 10.61 Claude Piquemal FRA 10.62 -0.6 1969 Valeriy Borzov URS 10.49 Alain Sarteur FRA 10.50 Philippe Clerc SUI 10.56 -2.7 1971 Valeriy Borzov URS 10.26 Gerhard Wucherer FRG 10.48 Vassilios Papageorgopoulos GRE 10.56 -1.3 1974 Valeriy Borzov URS 10.27 Pietro Mennea ITA 10.34 Klaus-Dieter Bieler FRG 10.35 -1.0 1978 Pietro Mennea ITA 10.27 Eugen Ray GDR 10.36 Vladimir Ignatenko URS 10.37 0.0 1982 Frank Emmelmann GDR 10. 21 Pierfrancesco Pavoni ITA 10. 25 Marian Woronin POL 10. 28 -080.8 1986 Linford Christie GBR 10.15 Steffen Bringmann GDR 10.20 Bruno Marie-Rose FRA 10.21 -0.1 1990 Linford Christie GBR 10.00w Daniel Sangouma FRA 10.04w John Regis GBR 10.07w 2.2 1994 Linford Christie GBR 10.14 Geir Moen NOR 10.20 Aleksandr Porkhomovskiy RUS 10.31 -0.5 1998 Darren Campbell GBR 10.04 Dwain Chambers GBR 10.10 Charalambos Papadias GRE 10.17 0.3 2002 Francis Obikwelu POR 10.06 -

Sport in Leeds Rugby (Generally Referred to As ‘Football’ Before the 1870S) ● the Football Essays Listed Above Cover Some Early Rugby History

● Leeds United: The Complete Record by M. Jarred and M. Macdonald (L 796.334 JAR) – Definitive study; also covers Leeds City (1904-1919). ● “Leeds United Football Club: The Formative Years 1919-1938” and “The Breakthrough Season 1964-5” – Photo-essays by D. Saffer and H. Dalphin, in Aspects of Leeds, vols. 2 & 3 (L 942.819 ASP). ● LUFC Match Day Programmes; newspaper supplements; fan magazines (e.g. The Hanging Sheep, The Peacock) – We hold various items from the 1960s to 2000s (see catalogue, under ‘Football’). Golf ● Guide to Yorkshire Golf by C. Scatchard (YP 796.352 SCA) – Potted histories of Leeds and Yorkshire golf clubs as of 1955. ● Some Yorkshire Golf Courses by Kolin Robertson (Y 796.352 ROB) – 1935 publication with descriptions of many Leeds courses, including Garforth, Horsforth, Moortown and Temple Newsam. Horse Racing ● Race Day Cards for Haigh Park Races (Leeds Race Ground) 1827-1832 (L 798.4 L517) and map of race course (ML 1823). ● A Short History of Wetherby Racecourse by J. Fairfax-Barraclough (LP W532 798). ● Sporting Days and Sporting Stories by J. Fairfax-Blakeborough (Y 798.4 BLA) – Includes various accounts of Wetherby and Leeds races Local and Family History and riders (see index of book). Research Guides Motor Sports ● Leeds Motor Club 1926 (LF 796.706 L517) – Scrapbook of newscuttings and photographs relating to motorbike and car racing. Sport in Leeds Rugby (Generally referred to as ‘football’ before the 1870s) ● The football essays listed above cover some early rugby history. Our Research Guides list some of the most useful, interesting and ● The Leeds Rugby League Story by D.