How Courageous Followers Stand up to Destructive Leadership a Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hitlers GP in England.Pdf

HITLER’S GRAND PRIX IN ENGLAND HITLER’S GRAND PRIX IN ENGLAND Donington 1937 and 1938 Christopher Hilton FOREWORD BY TOM WHEATCROFT Haynes Publishing Contents Introduction and acknowledgements 6 Foreword by Tom Wheatcroft 9 1. From a distance 11 2. Friends - and enemies 30 3. The master’s last win 36 4. Life - and death 72 5. Each dangerous day 90 6. Crisis 121 7. High noon 137 8. The day before yesterday 166 Notes 175 Images 191 Introduction and acknowledgements POLITICS AND SPORT are by definition incompatible, and they're combustible when mixed. The 1930s proved that: the Winter Olympics in Germany in 1936, when the President of the International Olympic Committee threatened to cancel the Games unless the anti-semitic posters were all taken down now, whatever Adolf Hitler decrees; the 1936 Summer Games in Berlin and Hitler's look of utter disgust when Jesse Owens, a negro, won the 100 metres; the World Heavyweight title fight in 1938 between Joe Louis, a negro, and Germany's Max Schmeling which carried racial undertones and overtones. The fight lasted 2 minutes 4 seconds, and in that time Louis knocked Schmeling down four times. They say that some of Schmeling's teeth were found embedded in Louis's glove... Motor racing, a dangerous but genteel activity in the 1920s and early 1930s, was touched by this, too, and touched hard. The combustible mixture produced two Grand Prix races at Donington Park, in 1937 and 1938, which were just as dramatic, just as sinister and just as full of foreboding. This is the full story of those races. -

Assignment Russia’ Review: Murrow’S Man in Moscow Khrushchev Called the 6-Foot-3 Marvin Kalb ‘Peter the Great’—And in Paris Shared Croissants with the CBS Reporter

DOW JONES, A NEWS CORP COMPANY About WSJ DJIA 32627.97 0.71% ▼ S&P 500 3913.10 0.06% ▼ Nasdaq 13215.24 0.76% ▲ U.S. 10 Yr 0/32 Yield 1.726% ▼ Crude Oil 61.44 0.03% ▲ Euro 1.1906 0.09% ▼ The Wall Street Journal John Kosner GET MARKETS ALERTS English Edition Print Edition Video Podcasts Latest Headlines Home World U.S. Politics Economy Business Tech Markets Opinion Life & Arts Real Estate WSJ. Magazine Search BEST OF GUIDE TO THE OSCAR NOMINATIONS WEEKEND READS BEST BOOKS OF FEBRUARY FRESH EYES ON THE FRICK COLLECTION LATEST MOVIE REVIEWS BEST SPY NOVELS Arts & Review BEST BOOKS OF 2020 BOOKS | BOOKSHELF SHARE ‘Assignment Russia’ Review: Murrow’s Man in Moscow Khrushchev called the 6-foot-3 Marvin Kalb ‘Peter the Great’—and in Paris shared croissants with the CBS reporter. By Edward Kosner March 18, 2021 7:04 pm ET SAVE PRINT TEXT Listen to this article 6 minutes Roger Mudd ascended to Network News Heaven at 93 last week. There he was reunited with Walter Cronkite, John Chancellor, Douglas Edwards, Howard K. Smith, Edward R. Murrow and other luminaries. Still with us are old hands Dan Rather, Diane Sawyer, Bernard Shaw, and the Kalb brothers, Marvin and Bernard—living witnesses to the days when TV news was more serious business and less partisan gasbaggery. Now Marvin Kalb, himself 90 but acute as ever, has written a memoir of his early career, especially his years as Moscow correspondent for CBS News in the direst period of the Cold War. -

Women and Asian Religions 1St Edition Kindle

WOMEN AND ASIAN RELIGIONS 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Zayn R Kassam | 9780275991593 | | | | | Women and Asian Religions 1st edition PDF Book New York Times. Coronavirus News U. This organization of American nuns had been in conflict with the Vatican over issues related to women's rights, including reproductive rights. Free shipping. Ideally, you should keep old books and manuscripts in protective boxes or sleeves made from acid-free materials. In countries like the U. Retrieved November 12, Archived from the original on October 31, If an antique book is torn or damaged, then do not use glue or tape on the pages and bindings, as this can devalue it. Archived from the original on May 12, Retrieved March 27, A larger culture section named "Omnivore" featured art, music, books, film, theater, food, travel, and television, including a weekly "Books" and "Want" section. So the aversion of religious leaders to gender equality may be a specific case of their more general endorsement of social inequality. Mother Jones. Not included, then, are the various animistic and shamanistic traditions counting the Chinese folk religion, which lacks consistency and is partly constructed on Taoist and Confucian beliefs , as well as the modern revival of ancient religions such as Neopaganism or Mexicayotl both traditions that were for a long time eradicated, and may differ in important ways from their original conception. Archived from the original on November 16, Though the most humanistic and least spiritual creed on this list, Confucianism does provide for a supernatural worldview it incorporates Heaven, the Lord on High, and divination influenced by Chinese folk tradition. -

Historical” Nixon Tapes”, President Richard Nixon, Washington Post and the New York Times, and Dan Elsberg

Historical” Nixon Tapes”, President Richard Nixon, Washington Post and The New York Times, and Dan Elsberg NIXON TAPES: "Get the Son of a B*tch" Ellsberg (Pentagon Papers) President Richard Nixon talks with his Attorney General John Mitchell about the leaked secret government documents about the Vietnam War, the Pentagon Papers. They first discuss the position of FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, who did not want to investigate the leaker, Daniel Ellsberg, because of his friendship with Ellsberg's father-in-law. Nixon descries some of the "softheads" in his administration who want him to go easy on Ellsberg. He notes that they need to "get the son of a b*tch" or else "wholesale thievery" would happen all over the government. The president feels that the P.R. might not be bad on their part, because people don't like thieves. (Photo: President Richard Nixon and his wife First Lady Pat Nixon walk with Gerald and Betty Ford to the helicopter Marine One on the day of Nixon's resignation from the presidency.) Uploaded on Aug 26, 2008 John Mitchell 006-021 June 29, 1971 White House Telephone NIXON TAPES: Angry at the New York Times (Haldeman) President Richard Nixon talks with his Chief of Staff H. R. (Bob) Haldeman about the press. In particular, he tells Haldeman about Henry Kissinger urging him to do an interview with New York Times reporter James (Scotty) Reston, Sr. Nixon, however, banned all interviews with the New York Times after the paper released the Pentagon Papers and ran an interview that Nixon disliked with Chinese leader Chou Enlai. -

By Raoul Felder Is the Classroom Safe? Mistreated Him

DOW JONES, A NEWS CORP COMPANY DJIA 27931.02 0.12% ▲ S&P 500 3372.85 0.02% ▼ Nasdaq 13019.09 0.20% ▼ U.S. 10 Yr 0/32 Yield 0.709% ▼ Crude Oil 42.23 0.52% ▲ Euro 1.1844 0.25% ▲ The Wall Street Journal John Kosner English Edition Print Edition Video Podcasts Latest Headlines Home World U.S. Politics Economy Business Tech Markets Opinion Life & Arts Real Estate WSJ. Magazine Search SHARE The Mayor Of Splitsville FACEBOOK A memoir in which a combative divorce lawyer pleads his own case. TWITTER Edward Kosner EMAIL Oct. 17, 2012 3:14 pm ET PERMALINK SAVE PRINT TEXT Raoul Felder is a macher—a brash operator, the model for the feral New York divorce lawyers called "bombers." A Brooklyn boy, he is the baby brother of the legendary songwriter Doc Pomus, the crony of comedian Jackie Mason, and a quote machine whose number was in every tabloid reporter's Rolodex back when reporters had Rolodexes. His new book, "Reflections in a Mirror," comes with a sly disclaimer tucked into a paragraph on page 10: "Memory or lack of memory caused me to invent some of [the story] or forced me to lie about the rest." But that hasn't kept him from delivering an entertaining if ramshackle memoir full of moving vignettes of family anguish and youthful striving, plus celebrity tattle about his roster of clients and their bizarre marital messes. Like any master litigator, Mr. Felder has a fondness for the sound of his own voice. Compelling chapters of his book are interrupted by grandiloquent riffs and inane shaggy- dog stories about sharing an elevator with Yankee slugger Reggie Jackson or being ignored at a party by Barbra Streisand and the Broadway producer David Merrick. -

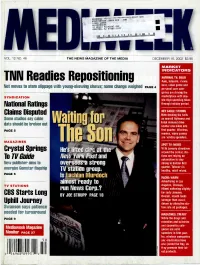

TNN Readies Repositioning

1.11 IAMUMME 078 #BXNQDWJ*******************3-DIGTT WW0098348# JUN04 ED9 488 LAURA JONES WALDENBOOKS 42 MOUNT PLEASANTAVE WHARTON, NJ 07885-2120 111-1111111 111111 VOL. 12 NO. 46 THE NEWS MAGAZINE OF THE MEDIA DECEMBER 16, 2002 $3.95 MARKET INDICATORS NATIONAL TV: SOLID TNN Readies Repositioning Auto, telecom, novie, beer, video game and Net moves to stem slippage with young -skewing shows; namechange weighed PAGE 4 pe-sonal care cate- go-ies are driving the marketplace with dou- SYNDICATION ble-digit spending hikes National Ratings through holiday period. NET CABLE: STRONG Claims Disputed Nets decking the halls as overall tightness and Some studios say cable Waiti brisk demand drive data should be broken out scatter rate hikes into first quarter. Wireless, PAGE 5 movies, video games are loliday spenders. MAGAZINES T SPOT TV: MIXED W.th January slowdown Crystal Springs He's J1:Jlij c at the anund the corner, sta- ticns are relying on To TV Guide Ne 'i r'st and automotive to stay New publisher aims to oversees a strong strong to bolster first quarter. Telecon is energize Gemstar flagship TV station group. healthy, retail mixed. PAGE 6 Is lAspIan Murdoch RADIO: WARM Advertising in Los al early to Angeles, Chicago, TV STATIONS run News Corp.? Mliami softening slightly for early January. CBS Starts Long BY JOE STRUPP PAGE 18 Overall, month looks stronger than usual, Uphill Journey dniven by attractive sta- Swanson says patience tion rate ad padkages. needed for turnaround MAGAZINES: STEADY While the drugs and PAGE 9 remedies and toiletries and cosmetics cate- Mediaweek Magazine gories are solid Monitor PAGE 27 spenders in first luar- ter, wireless companies anc electronics have els] joined the fray, as they promote their lat- est products. -

Some Major Advertisers Step up the Pressure on Magazines to Alter Their Content, Will Editors Bend?

THE by Russ Baker SOME MAJOR ADVERTISERS STEP UP THE PRESSURE ON MAGAZINES TO ALTER THEIR CONTENT, WILL EDITORS BEND? In an effort to avoid potential conflicts, s there any doubt that advertisers reason to hope that other advertisers it is required that Chrysler Corporation mumble and sometimes roar about won’t ask for the same privilege. be alerted in advance of any and all edi- reporting that can hurt them? You will have thirty or forty adver- torial content that encompasses sexual, I That the auto giants don’t like tisers checking through the pages. political, social issues or any editorial pieces that, say point to auto safety They will send notes to publishers. that might be construed as provocative problems? Or that Big Tobacco hates I don’t see how any good citizen or offensive. Each and every issue that to see its glamorous, cheerful ads doesn’t rise to this occasion and say carries Chrysler advertising requires a juxtaposed with articles mentioning this development is un-American Written summary outlining major their best customers’ grim way of and a threat to freedom.” theme/articles appearing in upcoming death? When advertisers disapprove Hyperbole? Maybe not. Just about issues. These summaries are to be for- of an editorial climate, they can- any editor will tell you: the ad/edit Warded to PentaCorn prior to closing in and sometimes do take a hike. chemistry is changing for the worse. order to give Ch ysler ample time to re- But for Chrysler to push beyond Corporations and their ad agencies view and reschedule if desired. -

The Inventory of the Edward Jay Epstein Collection #818

The Inventory of the Edward Jay Epstein Collection #818 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ... , EPSTEIN, EDWARD JAY (1935- ) Deposit May 1979 The Edward Jay Epstein Collection consists primarily of research material for three of Mr. Epstein's more prominent works: LEGEND: THE SECRET WORLD OF LEE HARVEY OSWALD, a study of the activ ities of the assassin of President John F. Kennedy prior to the assas sination; AGENCY OF FEAR: OPIATES AND POLITICAL POWER IN AMERICA, an investigation of the Nixon Admi.nistration's war on drugs in the early 197Os; and NEWS FROM NOWHERE: TELEVISION AND THE NEWS, a report on electronic journalism and the television industry•. The·~_Epstein Col lection also contains galleys and some notes pertaining to BETWEEN FACT AND FICTION: THE PROBLEM OF JOURNALISM as well as drafts of some of Mr. Epstein's articles and reviews. In addition, there are small amounts of personal material including correspondence and syllabi and student papers from college courses taught by Mr. Epstein and bits and pieces of various research projects. The extensive research material for LEGEND includes FBI, CIA, Secret Service and State Department files on Lee Harvey Oswald and Marina.·. Oswald, reports and interviews with Marines who served with Oswald and other persons who knew him and had contact with him prior to the Kennedy assassination. The AGENCY OF FEAR material contains a lengthy transcript of an interview with Egil Krogh, Deputy Assistant to the President for Domestic Affairs in the Nixon White House, and the White House files of Krogh and Jeffrey Donfeld, Staff Assistant to President Nixon, per taining to the Administration's war on drugs. -

Why Didn't Nixon Burn the Tapes and Other Questions About Watergate

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NSU Works Nova Law Review Volume 18, Issue 3 1994 Article 7 Why Didn’t Nixon Burn the Tapes and Other Questions About Watergate Stephen E. Ambrose∗ ∗ Copyright c 1994 by the authors. Nova Law Review is produced by The Berkeley Electronic Press (bepress). https://nsuworks.nova.edu/nlr Ambrose: Why Didn't Nixon Burn the Tapes and Other Questions About Waterga Why Didn't Nixon Bum the Tapes and Other Questions About Watergate Stephen E. Ambrose* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................... 1775 II. WHY DID THEY BREAK IN? ........... 1776 III. WHO WAS DEEP THROAT? .......... .. 1777 IV. WHY DIDN'T NIXON BURN THE TAPES? . 1778 V. VICE PRESIDENT FORD AND THE PARDON ........ 1780 I. INTRODUCTION For almost two years, from early 1973 to September, 1974, Watergate dominated the nation's consciousness. On a daily basis it was on the front pages-usually the headline; in the news magazines-usually the cover story; on the television news-usually the lead. Washington, D.C., a town that ordinarily is obsessed by the future and dominated by predictions about what the President and Congress will do next, was obsessed by the past and dominated by questions about what Richard Nixon had done and why he had done it. Small wonder: Watergate was the political story of the century. Since 1974, Watergate has been studied and commented on by reporters, television documentary makers, historians, and others. These commentators have had an unprecedented amount of material with which to work, starting with the tapes, the documentary record of the Nixon Administration, other material in the Nixon Presidential Materials Project, plus the transcripts of the various congressional hearings, the courtroom testimony of the principal actors, and the memoirs of the participants. -

'Crying the News' Review: Street-Corner Capitalists

DOW JONES, A NEWS CORP COMPANY DJIA 27839.83 0.49% ▼ S&P 500 3369.93 0.31% ▼ Nasdaq 11025.38 0.12% ▲ U.S. 10 Yr -12/32 Yield 0.712% ▼ Crude Oil 42.29 0.89% ▼ Euro 1.1800 0.12% ▲ The Wall Street Journal John Kosner English Edition Print Edition Video Podcasts Latest Headlines Home World U.S. Politics Economy Business Tech Markets Opinion Life & Arts Real Estate WSJ. Magazine Search BOOKS | BOOKSHELF SHARE FACEBOOK‘Crying the News’ Review: Street-Corner Capitalists TWITTERThe newsboy doggedly hawking papers for pennies on city streets was once a staple of American life, an icon of unflagging industry. EMAIL PERMALINK PHOTO: GETTY IMAGES By Edward Kosner Oct. 6, 2019 4:26 pm ET SAVE PRINT TEXT 9 Thomas Edison was one. So were Harry Houdini, Herbert Hoover, W.C. Fields, Walt Disney, Benjamin Franklin, Jackie Robinson, Walter Winchell, Thomas Wolfe, Jack London, Knute Rockne, Harry Truman, John Wayne, Warren Buffett and many more familiar names. Besides being illustrious Americans, these men shared a calling—growing up, they were newsboys, delivering newspapers to subscribers or, more colorfully, hawking them on the streets for a couple of pennies, real money in those days. In their time, newsboys (girls were rare) were American icons—symbols of unflagging industry and tattered, barefoot, shivering objects of pity. They had their own argot and better news judgment than many editors, because they had to size up the appeal of every edition to determine how many copies to buy from the publisher. Some used hawking as a cover for picking pockets, but most were as honest as they could afford to be. -

July 1-15, 1971

RICHARD NIXON PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY DOCUMENT WITHDRAWAL RECORD DOCUMENT DOCUMENT SUBJECT/TITLE OR CORRESPONDENTS DATE RESTRICTION NUMBER TYPE 1 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 7/15/1971 A Appendix “A” 2 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 7/3/1971 A Appendix “A” 3 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 7/5/1971 A Appendix “A” 4 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 7/6/1971 A Appendix “B” COLLECTION TITLE BOX NUMBER WHCF: SMOF: Office of Presidential Papers and Archives RC-8 FOLDER TITLE President Richard Nixon’s Daily Diary July 1, 1971 – July 15, 1971 PRMPA RESTRICTION CODES: A. Release would violate a Federal statute or Agency Policy. E. Release would disclose trade secrets or confidential commercial or B. National security classified information. financial information. C. Pending or approved claim that release would violate an individual’s F. Release would disclose investigatory information compiled for law rights. enforcement purposes. D. Release would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of privacy G. Withdrawn and return private and personal material. or a libel of a living person. H. Withdrawn and returned non-historical material. DEED OF GIFT RESTRICTION CODES: D-DOG Personal privacy under deed of gift -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION *U.S. GPO; 1989-235-084/00024 NA 14021 (4-85) THE WHITE HOUSE TIME DAY WASHINGTON, D. C. - 8:35 a.m. THURSDAY PHONE TIME P=Placed R=Received ACTIVITY Out 1.0 to 8:35 The President had breakfast. 8:41 The President went to the Oval Office. 8:41 8:45 The President met with his Deputy Assistant, Alexander P. Butterfield•. 8:45 9:18 The President met with his Assistant, H. -

Lesson Plans for Teaching English and American Studies

American Values Through Film: Lesson Plans for Teaching English and American Studies Table of Contents How to Use this CD 2 Introduction, Bridget F. Gersten (ELO) 3 Letter of Thanks 5 Checklist for Lesson Plan Review 7 Description of Films with Themes 10 Copyright and Fair Use Guidelines for Teachers 13 Sample Lesson Plan Twelve Angry Men by an English Language Fellow 18 Lesson Plans All the President’s Men 23 Bibliography 166 Web Resource 168 2006 American Values through Film --English Language Office (ELO) Moscow 1 American Values through Film English Language Office Public Affairs section U.S. Embassy, Moscow www.usembassy.ru/english HOW TO USE THIS CD-ROM This CD-Rom has a collection of PDF files that require Adobe Acrobat Reader (AAR). The AAR is loaded on this CD and should launch or install automatically when you put the CD in. You will need the AAR your computer in order to use the CD. Here is how to use the CD-Rom: Insert the CD into the CD drive of your computer. The program should launch/turn on automatically and you should use the File, Open command to open any of the PDF files you wish to use. If the CD does not automatically launch when you insert it into your CD drive, please launch it manually by clicking on the PDF files that look like this on your screen The CD has 7 individual PDF files, each with some material related to the teaching of English through film and individual lesson plans. Each PDF file has a selection of lesson plans written by teachers of English in Russia.