Civil Affairs: a Force for Influence in Competition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Military Guide to Terrorism in the Twenty-First Century

US Army TRADOC TRADOC G2 Handbook No. 1 AA MilitaryMilitary GuideGuide toto TerrorismTerrorism in the Twenty-First Century US Army Training and Doctrine Command TRADOC G2 TRADOC Intelligence Support Activity - Threats Fort Leavenworth, Kansas 15 August 2007 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited. 1 Summary of Change U.S. Army TRADOC G2 Handbook No. 1 (Version 5.0) A Military Guide to Terrorism in the Twenty-First Century Specifically, this handbook dated 15 August 2007 • Provides an information update since the DCSINT Handbook No. 1, A Military Guide to Terrorism in the Twenty-First Century, publication dated 10 August 2006 (Version 4.0). • References the U.S. Department of State, Office of the Coordinator for Counterterrorism, Country Reports on Terrorism 2006 dated April 2007. • References the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC), Reports on Terrorist Incidents - 2006, dated 30 April 2007. • Deletes Appendix A, Terrorist Threat to Combatant Commands. By country assessments are available in U.S. Department of State, Office of the Coordinator for Counterterrorism, Country Reports on Terrorism 2006 dated April 2007. • Deletes Appendix C, Terrorist Operations and Tactics. These topics are covered in chapter 4 of the 2007 handbook. Emerging patterns and trends are addressed in chapter 5 of the 2007 handbook. • Deletes Appendix F, Weapons of Mass Destruction. See TRADOC G2 Handbook No.1.04. • Refers to updated 2007 Supplemental TRADOC G2 Handbook No.1.01, Terror Operations: Case Studies in Terror, dated 25 July 2007. • Refers to Supplemental DCSINT Handbook No. 1.02, Critical Infrastructure Threats and Terrorism, dated 10 August 2006. • Refers to Supplemental DCSINT Handbook No. -

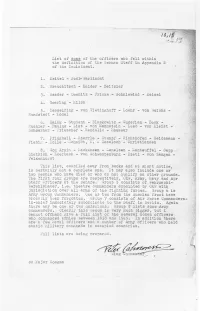

List of Some of the Officers ~~10 Fall Within the Definition of the German

-------;-:-~---,-..;-..............- ........- List of s ome of t he officers ~~10 fall within t he de finition of t he German St af f . in Appendix B· of t he I n cii c tment . 1 . Kei t e l - J odl- Aar l imont 2 . Br auchi t s ch - Halder - Zei t zl er 3. riaeder - Doeni t z - Fr i cke - Schni ewi nd - Mei s el 4. Goer i ng - fu i l ch 5. Kes s el r i ng ~ von Vi et i nghof f - Loehr - von ~e i c h s rtun c1 s t ec t ,.. l.io d eL 6. Bal ck - St ude nt - Bl a skowi t z - Gud er i an - Bock Kuchl er - Pa ul us - Li s t - von Manns t ei n - Leeb - von Kl e i ~ t Schoer ner - Fr i es sner - Rendul i c - Haus s er 7. Pf l ug bei l - Sper r l e - St umpf - Ri cht hof en - Sei a emann Fi ebi £; - Eol l e - f)chmi dt , E .- Des s l och - .Christiansen 8 . Von Arni m - Le ck e ris en - :"emelsen - l.~ a n t e u f f e l - Se pp . J i et i i ch - 1 ber ba ch - von Schweppenburg - Di e t l - von Zang en t'al kenhol's t rr hi s' list , c ompiled a way f r om books and a t. shor t notice, is c ertai nly not a complete one . It may also include one or t .wo neop .le who have ai ed or who do not q ual ify on other gr ounds . -

Assessing the Implications of Possible Changes to Women in Service Restrictions: Practices of Foreign Militaries and Other Organizations

Assessing the Implications of Possible Changes to Women in Service Restrictions: Practices of Foreign Militaries and Other Organizations Annemarie Randazzo-Matsel • Jennifer Schulte • Jennifer Yopp DIM-2012-U-000689-Final July 2012 Photo credit line: Young Israeli women undergo tough, initial pre-army training at Zikim Army Base in southern Israel. REUTERS/Nir Elias Approved for distribution: July 2012 Anita Hattiangadi Research Team Leader Marine Corps Manpower Team Resource Analysis Division This document represents the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the Department of the Navy. Cleared for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited. Specific authority: N00014-11-D-0323. Copies of this document can be obtained through the CNA Document Control and Distribution Section at 703-824-2123. Copyright 2012 CNA This work was created in the performance of Federal Government Contract Number N00014-11-D-0323. Any copyright in this work is subject to the Government's Unlimited Rights license as defined in DFARS 252.227-7013 and/or DFARS 252.227-7014. The reproduction of this work for commercial purposes is strictly prohibited. Nongovernmental users may copy and distribute this document in any medium, either commercially or noncommercially, provided that this copyright notice is reproduced in all copies. Nongovernmental users may not use technical measures to obstruct or control the read-ing or further copying of the copies they make or distribute. Nongovernmental users may not accept compensation of any manner in exchange for copies. All other rights reserved. Contents Executive summary . 1 Foreign militaries . 3 Australia . 4 ADF composition . -

Meeting the Anti-Access and Area-Denial Challenge

Meeting the Anti-Access and Area-Denial Challenge Andrew Krepinevich, Barry Watts & Robert Work 1730 Rhode Island Avenue, NW, Suite 912 Washington, DC 20036 Meeting the Anti-Access and Area-Denial Challenge by Andrew Krepinevich Barry Watts Robert Work Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments 2003 ABOUT THE CENTER FOR STRATEGIC AND BUDGETARY ASSESSMENTS The Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments is an independent public policy research institute established to promote innovative thinking about defense planning and investment strategies for the 21st century. CSBA’s analytic-based research makes clear the inextricable link between defense strategies and budgets in fostering a more effective and efficient defense, and the need to transform the US military in light of the emerging military revolution. CSBA is directed by Dr. Andrew F. Krepinevich and funded by foundation, corporate and individual grants and contributions, and government contracts. 1730 Rhode Island Ave., NW Suite 912 Washington, DC 20036 (202) 331-7990 http://www.csbaonline.org CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................... I I. NEW CHALLENGES TO POWER PROJECTION.................................................................. 1 II. PROSPECTIVE US AIR FORCE FAILURE POINTS........................................................... 11 III. THE DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY AND ASSURED ACCESS: A CRITICAL RISK ASSESSMENT .29 IV. THE ARMY AND THE OBJECTIVE FORCE ..................................................................... 69 V. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS .................................................................... 93 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY During the Cold War, the United States defense posture called for substantial forces to be located overseas as part of a military strategy that emphasized deterrence and forward defense. Large combat formations were based in Europe and Asia. Additional forces—both land-based and maritime—were rotated periodically back to the rear area in the United States. -

Nigeria: the Challenge of Military Reform

Nigeria: The Challenge of Military Reform Africa Report N°237 | 6 June 2016 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. The Long Decline .............................................................................................................. 3 A. The Legacy of Military Rule ....................................................................................... 3 B. The Military under Democracy: Failed Promises of Reform .................................... 4 1. The Obasanjo years .............................................................................................. 4 2. The Yar’Adua and Jonathan years ....................................................................... 7 3. The military’s self-driven attempts at reform ...................................................... 8 III. Dimensions of Distress ..................................................................................................... 9 A. The Problems of Leadership and Civilian Oversight ................................................ -

Conrad Von Hötzendorf and the “Smoking Gun”: a Biographical Examination of Responsibility and Traditions of Violence Against Civilians in the Habsburg Army 55

1914: Austria-Hungary, the Origins, and the First Year of World War I Günter Bischof, Ferdinand Karlhofer (Eds.) Samuel R. Williamson, Jr. (Guest Editor) CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | VOLUME 23 uno press innsbruck university press Copyright © 2014 by University of New Orleans Press, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to UNO Press, University of New Orleans, LA 138, 2000 Lakeshore Drive. New Orleans, LA, 70119, USA. www.unopress.org. Printed in the United States of America Design by Allison Reu Cover photo: “In enemy position on the Piave levy” (Italy), June 18, 1918 WK1/ALB079/23142, Photo Kriegsvermessung 5, K.u.k. Kriegspressequartier, Lichtbildstelle Vienna Cover photo used with permission from the Austrian National Library – Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Vienna Published in the United States by Published and distributed in Europe University of New Orleans Press by Innsbruck University Press ISBN: 9781608010264 ISBN: 9783902936356 uno press Contemporary Austrian Studies Sponsored by the University of New Orleans and Universität Innsbruck Editors Günter Bischof, CenterAustria, University of New Orleans Ferdinand Karlhofer, Universität Innsbruck Assistant Editor Markus Habermann -

India's National Security Annual Review 2010

Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:22 24 May 2016 India’s National Security Annual Review 2010 Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:22 24 May 2016 216x138 HB + 8colour pages ii Ç India’s National Security This series, India’s National Security: Annual Review, was con- ceptualised in the year 2000 in the wake of India’s nuclear tests and the Kargil War in order to provide an in-depth and holistic assessment of national security threats and challenges and to enhance the level of national security consciousness in the country. The first volume was published in 2001. Since then, nine volumes have been published consecutively. The series has been supported by the National Security Council Secretariat and the Confederation of Indian Industry. Its main features include a review of the national security situation, an analysis of upcoming threats and challenges by some of the best minds in India, a periodic National Security Index of fifty top countries of the world, and a chronology of major events. It now serves as an indispensable source of information and analysis on critical national security issues of India. Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:22 24 May 2016 India’s National Security Annual Review 2010 Editor-in-Chief SATISH KUMAR Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:22 24 May 2016 LONDON NEW YORK NEW DELHI Under the auspices of Foundation for National Security Research, New Delhi First published 2011 in India by Routledge 912 Tolstoy House, 15–17 Tolstoy Marg, Connaught Place, New Delhi 110 001 Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Transferred to Digital Printing 2011 © 2010 Satish Kumar Typeset by Star Compugraphics Private Ltd D–156, Second Floor Sector 7, NOIDA 201 301 All rights reserved. -

Hybrid Threats in the 21St Century

Band 17 / 2016 Band 17 / 2016 Die Vernetzung von Gesellschaften wird durch technische Errungenschaften immer komplexer. Somit erweitern Century sich auch Einflussfaktoren auf die Sicherheit von Gesell- st schaftssystemen. Networked Insecurity – Spricht man in diesem Zusammenhang in sicherheits- politischen Fachkreisen von hybrider Kampfführung, ge- hen die Autoren in diesem Buch einen Schritt weiter und Hybrid Threats beschäftigen sich mit Optionen der Machtprojektion, die st über Kampfhandlungen hinausgehen. Dabei sehen sie in the 21 Century hybride Bedrohungen als sicherheitspolitische Herausfor- derung der Zukunft. Beispiele dazu untermauern den im Buch vorangestellten theoretischen Teil. Mögliche Hand- lungsoptionen runden diese Publikation ab. Networked Insecurity – Hybrid Threats in the 21 Threats – Hybrid Insecurity Networked ISBN: 978-3-903121-01-0 Anton Dengg and Michael Schurian (Eds.) 17/16 Schriftenreihe der Dengg, Schurian (Eds.) Dengg, Landesverteidigungsakademie Schriftenreihe der Landesverteidigungsakademie Anton Dengg, Michael Schurian (Eds.) Networked Insecurity – Hybrid Threats in the 21st Century 17/2016 Vienna, June 2016 Imprint: Copyright, Production, Publisher: Republic of Austria / Federal Ministry of Defence and Sports Rossauer Lände 1 1090 Vienna, Austria Edited by: National Defence Academy Institute for Peace Support and Conflict Management Stiftgasse 2a 1070 Vienna, Austria Schriftenreihe der Landesverteidigungsakademie Copyright © Republic of Austria / Federal Ministry of Defence and Sports All rights reserved -

Ground Combat Overmatch Through Control of the Atmospheric

Romanian soldier fires rocket propelled grenade at range near Bemowo Piskie Training Area, Poland, January 24, 2018, as part of multinational battle group comprised of U.S., UK, Croatian, and Romanian soldiers supporting NATO’s Enhanced Forward Presence (U.S. Army/Andrew McNeil) he U.S. military is seeking dis- Ground Combat ruptive innovations to sustain T its technological advantage despite rapid advances by potential adversaries. The need is particularly Overmatch Through acute in ground combat, where most U.S. casualties are sustained and where game-changing technical innovations Control of the have been less common than in other military mission areas. The Search for Tactical Atmospheric Littoral Overmatch In addition to increasing technologi- By George M. Dougherty cal pressure, recent coalition combat experiences and defense studies suggest that the future battlefield will be more complex than in the past. Combat in built-up areas including megacities will become commonplace. As concluded Colonel George M. Dougherty, USAF, is the Individual Mobilization Augmentee to the Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Science, Technology, and Engineering, Office of the Assistant Secretary of by a recent report, “Urban operations the Air Force for Acquisition and Logistics, in Washington, DC. in the 21st century are not just another 64 Features / Control of the Atmospheric Littoral JFQ 94, 3rd Quarter 2019 type of operation; they will become this tion of robotics and autonomy to forces can move, concentrate, and century’s signature form of warfare.”1 the land domain has focused largely disperse without hindrance, much The pivotal battles in Iraq and Syria on unmanned ground vehicles. -

DEPARTMENT of the ARMY the Pentagon, Washington, DC 20310 Phone (703) 695–2442

DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY The Pentagon, Washington, DC 20310 phone (703) 695–2442 SECRETARY OF THE ARMY 101 Army Pentagon, Room 3E700, Washington, DC 20310–0101 phone (703) 695–1717, fax (703) 697–8036 Secretary of the Army.—Dr. Mark T. Esper. Executive Officer.—COL Joel Bryant ‘‘JB’’ Vowell. UNDER SECRETARY OF THE ARMY 102 Army Pentagon, Room 3E700, Washington, DC 20310–0102 phone (703) 695–4311, fax (703) 697–8036 Under Secretary of the Army.—Ryan D. McCarthy. Executive Officer.—COL Patrick R. Michaelis. CHIEF OF STAFF OF THE ARMY (CSA) 200 Army Pentagon, Room 3E672, Washington, DC 20310–0200 phone (703) 697–0900, fax (703) 614–5268 Chief of Staff of the Army.—GEN Mark A. Milley. Vice Chief of Staff of the Army.—GEN James C. McConville (703) 695–4371. Executive Officers: COL Milford H. Beagle, Jr., 695–4371; COL Joseph A. Ryan. Director of the CSA Staff Group.—COL Peter N. Benchoff, Room 3D654 (703) 693– 8371. Director of the Army Staff.—LTG Gary H. Cheek, Room 3E663, 693–7707. Sergeant Major of the Army.—SMA Daniel A. Dailey, Room 3E677, 695–2150. Directors: Army Protocol.—Michele K. Fry, Room 3A532, 692–6701. Executive Communications and Control.—Thea Harvell III, Room 3D664, 695–7552. Joint and Defense Affairs.—COL Anthony W. Rush, Room 3D644 (703) 614–8217. Direct Reporting Units Commanding General, U.S. Army Test and Evaluation Command.—MG John W. Charlton (443) 861–9954 / 861–9989. Superintendent, U.S. Military Academy.—LTG Robert L. Caslen, Jr. (845) 938–2610. Commanding General, U.S. Army Military District of Washington.—MG Michael L. -

Lieutenant Colonel Retired, Angela Marie Greenewald Was Born and Raised in the Schenectady, New York Area

Lieutenant Colonel Retired, Angela Marie Greenewald was born and raised in the Schenectady, New York area. After graduating from The College of Saint Rose she was commissioned as a Field Artillery Officer in 1998. LTC Greenewald’s first assignments included being a Battery Executive Officer in Echo Battery, 1/79th Field Artillery Battalion as well as serving as one of the first female Battery Executive Officer in a Field Artillery Basic Combat Training, Training and Development Command course. After attending the Transportation Officer Branch Qualification Course in 2000, LTC Greenewald served as a Platoon Leader in the 15th Transportation Company, 19th Maintenance Battalion at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Following this assignment LTC Greenewald served in the 302nd Forward Support Battalion in Camp Casey, Korea as the Battalion Adjutant and then attended the Combined Logistics Officer Advanced Course in Fort Lee Virginia. As a Movement Control Detachment Commander for Corps Support Command, Fort Bragg, North Carolina she deployed to Kuwait in support of Operation Enduring Freedom I where she was responsible for the reception, staging, onward movement and integration of men and material initially from the Seaport of Embarkation in Shuaiba Port, Kuwait to forward staging location; and then ran the Airport of Embarkation in Tallil Air Base, Iraq throughout theater, particularly Baghdad in support of the main effort. Returning to Korea in 2004, LTC Greenewald commanded a company in Area III in Camp Humphreys, Korea. In 2005, LTC Greenewald graduated from the Civil Affairs Qualification Course, Regional Studies Course with a focus on Africa and French language training and was subsequently assigned to the 96th Civil Affairs Battalion (Airborne). -

The Peacebuilding Dilemma: Civil-Military Cooperation in Stability Operations

International Journal of Peace Studies, Volume 11, Number 2, Autumn/Winter 2006 THE PEACEBUILDING DILEMMA: CIVIL-MILITARY COOPERATION IN STABILITY OPERATIONS Volker Franke Abstract The nature of complex humanitarian relief, peacebuilding, and reconstruction missions increasingly forces military and civilian actors to operate in the same space at the same time thereby challenging their ability to remain impartial, neutral and independent. The purpose of this article is to explore the cultural, organizational, operational, and normative differences between civilian and military relief and security providers in contemporary stability operations and to develop recommendations for improving civil- military cooperation (CIMIC) in order to aid the provision of more effective relief, stabilization, and transformation operations. At 8:30 a.m. local time on October 27, 2003 an ambulance packed with explosives rammed into security barriers outside the Red Cross headquarters in Baghdad killing some 40 people, including two Iraqi International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) employees, and leaving more than 200 wounded. The ICRC announced immediately following the attacks withdrawal of its international staff from Baghdad, thereby reducing vital programs and services to the most vulnerable segments of the population. The October suicide bombing came two months after the August 19 attack on the United Nations (UN) headquarters in Baghdad that left 23 people dead, including Sergio Vieira de Mello, the Secretary General’s Special Representative in Iraq. Expressing horror and consternation, United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) head Mark Malloch Brown surmised on the day of the August attack: “We do this [humanitarian relief] out of vocation. We are apolitical. We were here to help the people of Iraq and help them return to self-government.