Hybrid Threats in the 21St Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

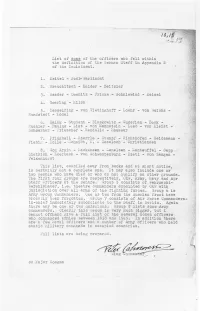

List of Some of the Officers ~~10 Fall Within the Definition of the German

-------;-:-~---,-..;-..............- ........- List of s ome of t he officers ~~10 fall within t he de finition of t he German St af f . in Appendix B· of t he I n cii c tment . 1 . Kei t e l - J odl- Aar l imont 2 . Br auchi t s ch - Halder - Zei t zl er 3. riaeder - Doeni t z - Fr i cke - Schni ewi nd - Mei s el 4. Goer i ng - fu i l ch 5. Kes s el r i ng ~ von Vi et i nghof f - Loehr - von ~e i c h s rtun c1 s t ec t ,.. l.io d eL 6. Bal ck - St ude nt - Bl a skowi t z - Gud er i an - Bock Kuchl er - Pa ul us - Li s t - von Manns t ei n - Leeb - von Kl e i ~ t Schoer ner - Fr i es sner - Rendul i c - Haus s er 7. Pf l ug bei l - Sper r l e - St umpf - Ri cht hof en - Sei a emann Fi ebi £; - Eol l e - f)chmi dt , E .- Des s l och - .Christiansen 8 . Von Arni m - Le ck e ris en - :"emelsen - l.~ a n t e u f f e l - Se pp . J i et i i ch - 1 ber ba ch - von Schweppenburg - Di e t l - von Zang en t'al kenhol's t rr hi s' list , c ompiled a way f r om books and a t. shor t notice, is c ertai nly not a complete one . It may also include one or t .wo neop .le who have ai ed or who do not q ual ify on other gr ounds . -

Assessing the Implications of Possible Changes to Women in Service Restrictions: Practices of Foreign Militaries and Other Organizations

Assessing the Implications of Possible Changes to Women in Service Restrictions: Practices of Foreign Militaries and Other Organizations Annemarie Randazzo-Matsel • Jennifer Schulte • Jennifer Yopp DIM-2012-U-000689-Final July 2012 Photo credit line: Young Israeli women undergo tough, initial pre-army training at Zikim Army Base in southern Israel. REUTERS/Nir Elias Approved for distribution: July 2012 Anita Hattiangadi Research Team Leader Marine Corps Manpower Team Resource Analysis Division This document represents the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the Department of the Navy. Cleared for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited. Specific authority: N00014-11-D-0323. Copies of this document can be obtained through the CNA Document Control and Distribution Section at 703-824-2123. Copyright 2012 CNA This work was created in the performance of Federal Government Contract Number N00014-11-D-0323. Any copyright in this work is subject to the Government's Unlimited Rights license as defined in DFARS 252.227-7013 and/or DFARS 252.227-7014. The reproduction of this work for commercial purposes is strictly prohibited. Nongovernmental users may copy and distribute this document in any medium, either commercially or noncommercially, provided that this copyright notice is reproduced in all copies. Nongovernmental users may not use technical measures to obstruct or control the read-ing or further copying of the copies they make or distribute. Nongovernmental users may not accept compensation of any manner in exchange for copies. All other rights reserved. Contents Executive summary . 1 Foreign militaries . 3 Australia . 4 ADF composition . -

Nigeria: the Challenge of Military Reform

Nigeria: The Challenge of Military Reform Africa Report N°237 | 6 June 2016 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. The Long Decline .............................................................................................................. 3 A. The Legacy of Military Rule ....................................................................................... 3 B. The Military under Democracy: Failed Promises of Reform .................................... 4 1. The Obasanjo years .............................................................................................. 4 2. The Yar’Adua and Jonathan years ....................................................................... 7 3. The military’s self-driven attempts at reform ...................................................... 8 III. Dimensions of Distress ..................................................................................................... 9 A. The Problems of Leadership and Civilian Oversight ................................................ -

Conrad Von Hötzendorf and the “Smoking Gun”: a Biographical Examination of Responsibility and Traditions of Violence Against Civilians in the Habsburg Army 55

1914: Austria-Hungary, the Origins, and the First Year of World War I Günter Bischof, Ferdinand Karlhofer (Eds.) Samuel R. Williamson, Jr. (Guest Editor) CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | VOLUME 23 uno press innsbruck university press Copyright © 2014 by University of New Orleans Press, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to UNO Press, University of New Orleans, LA 138, 2000 Lakeshore Drive. New Orleans, LA, 70119, USA. www.unopress.org. Printed in the United States of America Design by Allison Reu Cover photo: “In enemy position on the Piave levy” (Italy), June 18, 1918 WK1/ALB079/23142, Photo Kriegsvermessung 5, K.u.k. Kriegspressequartier, Lichtbildstelle Vienna Cover photo used with permission from the Austrian National Library – Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Vienna Published in the United States by Published and distributed in Europe University of New Orleans Press by Innsbruck University Press ISBN: 9781608010264 ISBN: 9783902936356 uno press Contemporary Austrian Studies Sponsored by the University of New Orleans and Universität Innsbruck Editors Günter Bischof, CenterAustria, University of New Orleans Ferdinand Karlhofer, Universität Innsbruck Assistant Editor Markus Habermann -

India's National Security Annual Review 2010

Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:22 24 May 2016 India’s National Security Annual Review 2010 Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:22 24 May 2016 216x138 HB + 8colour pages ii Ç India’s National Security This series, India’s National Security: Annual Review, was con- ceptualised in the year 2000 in the wake of India’s nuclear tests and the Kargil War in order to provide an in-depth and holistic assessment of national security threats and challenges and to enhance the level of national security consciousness in the country. The first volume was published in 2001. Since then, nine volumes have been published consecutively. The series has been supported by the National Security Council Secretariat and the Confederation of Indian Industry. Its main features include a review of the national security situation, an analysis of upcoming threats and challenges by some of the best minds in India, a periodic National Security Index of fifty top countries of the world, and a chronology of major events. It now serves as an indispensable source of information and analysis on critical national security issues of India. Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:22 24 May 2016 India’s National Security Annual Review 2010 Editor-in-Chief SATISH KUMAR Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:22 24 May 2016 LONDON NEW YORK NEW DELHI Under the auspices of Foundation for National Security Research, New Delhi First published 2011 in India by Routledge 912 Tolstoy House, 15–17 Tolstoy Marg, Connaught Place, New Delhi 110 001 Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Transferred to Digital Printing 2011 © 2010 Satish Kumar Typeset by Star Compugraphics Private Ltd D–156, Second Floor Sector 7, NOIDA 201 301 All rights reserved. -

DEPARTMENT of the ARMY the Pentagon, Washington, DC 20310 Phone (703) 695–2442

DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY The Pentagon, Washington, DC 20310 phone (703) 695–2442 SECRETARY OF THE ARMY 101 Army Pentagon, Room 3E700, Washington, DC 20310–0101 phone (703) 695–1717, fax (703) 697–8036 Secretary of the Army.—Dr. Mark T. Esper. Executive Officer.—COL Joel Bryant ‘‘JB’’ Vowell. UNDER SECRETARY OF THE ARMY 102 Army Pentagon, Room 3E700, Washington, DC 20310–0102 phone (703) 695–4311, fax (703) 697–8036 Under Secretary of the Army.—Ryan D. McCarthy. Executive Officer.—COL Patrick R. Michaelis. CHIEF OF STAFF OF THE ARMY (CSA) 200 Army Pentagon, Room 3E672, Washington, DC 20310–0200 phone (703) 697–0900, fax (703) 614–5268 Chief of Staff of the Army.—GEN Mark A. Milley. Vice Chief of Staff of the Army.—GEN James C. McConville (703) 695–4371. Executive Officers: COL Milford H. Beagle, Jr., 695–4371; COL Joseph A. Ryan. Director of the CSA Staff Group.—COL Peter N. Benchoff, Room 3D654 (703) 693– 8371. Director of the Army Staff.—LTG Gary H. Cheek, Room 3E663, 693–7707. Sergeant Major of the Army.—SMA Daniel A. Dailey, Room 3E677, 695–2150. Directors: Army Protocol.—Michele K. Fry, Room 3A532, 692–6701. Executive Communications and Control.—Thea Harvell III, Room 3D664, 695–7552. Joint and Defense Affairs.—COL Anthony W. Rush, Room 3D644 (703) 614–8217. Direct Reporting Units Commanding General, U.S. Army Test and Evaluation Command.—MG John W. Charlton (443) 861–9954 / 861–9989. Superintendent, U.S. Military Academy.—LTG Robert L. Caslen, Jr. (845) 938–2610. Commanding General, U.S. Army Military District of Washington.—MG Michael L. -

Comparative Connections, Volume 11, Number 3

Pacific Forum CSIS Comparative Connections A Quarterly E-Journal on East Asian Bilateral Relations edited by Brad Glosserman Carl Baker 3rd Quarter (July-September) 2009 Vol. 11, No.3 October 2009 http://csis.org/program/comparative-connections Pacific Forum CSIS Based in Honolulu, Hawaii, the Pacific Forum CSIS operates as the autonomous Asia- Pacific arm of the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C. Founded in 1975, the thrust of the Forum’s work is to help develop cooperative policies in the Asia- Pacific region through debate and analyses undertaken with the region’s leaders in the academic, government, and corporate arenas. The Forum’s programs encompass current and emerging political, security, economic/business, and oceans policy issues. It collaborates with a network of more than 30 research institutes around the Pacific Rim, drawing on Asian perspectives and disseminating its projects’ findings and recommendations to opinion leaders, governments, and publics throughout the region. An international Board of Governors guides the Pacific Forum’s work. The Forum is funded by grants from foundations, corporations, individuals, and governments, the latter providing a small percentage of the forum’s $1.2 million annual budget. The Forum’s studies are objective and nonpartisan and it does not engage in classified or proprietary work. Comparative Connections A Quarterly E-Journal on East Asian Bilateral Relations Edited by Brad Glosserman and Carl Baker Volume 11, Number 3 Third Quarter (July-September) 2009 Honolulu, Hawaii October 2009 Comparative Connections A Quarterly Electronic Journal on East Asian Bilateral Relations Bilateral relationships in East Asia have long been important to regional peace and stability, but in the post-Cold War environment, these relationships have taken on a new strategic rationale as countries pursue multiple ties, beyond those with the U.S., to realize complex political, economic, and security interests. -

BIOGRAPHY General Carter F. Ham, U.S. Army, Retired

BIOGRAPHY General Carter F. Ham, U.S. Army, Retired General Ham is the president and chief executive officer of the Association of the United States Army. He is an experienced leader who has led at every level from platoon to geographic combatant command. He is also a member of a very small group of Army senior leaders who have risen from private to four-star general. General Ham served as an enlisted infantryman in the 82nd Airborne Division before attending John Carroll University in Cleveland, Ohio. Graduating in 1976 as a distinguished military graduate, his service has taken him to Italy, Germany, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Macedonia, Qatar, Iraq and, uniquely among Army leaders, to over 40 African countries in addition to a number of diverse assignments within the United States. He commanded the First Infantry Division, the legendary Big Red One, before assuming duties as director for operations on the Joint Staff at the Pentagon where he oversaw all global operations. His first four-star command was as commanding general, U.S. Army Europe. Then in 2011, he became just the second commander of United States Africa Command where he led all U.S. military activities on the African continent ranging from combat operations in Libya to hostage rescue operations in Somalia as well as training and security assistance activities across 54 complex and diverse African nations. General Ham retired in June of 2013 after nearly 38 years of service. Immediately prior to joining the staff at AUSA, he served as the chairman of the National Commission on the Future of the Army, an eight-member panel tasked by the Congress with making recommendations on the size, force structure and capabilities of the Total Army. -

Stars on Their Shoulders. Blood on Their Hands. War Crimes Committed

STARS ON THEIR SHOULDERS. BLOOD ON THEIR HANDS. WAR CRIMES COMMITTED BY THE NIGERIAN MILITARY Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2015 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2015 Index: AFR 44/1657/2015 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Nigerian troops inspect the former emir's palace that was used by Boko Haram as their headquarters but was burnt down when they fled Bama on March 25, 2015. Nigeria's military has retaken the northeastern town of Bama from Boko Haram, but signs of mass killings carried out by Boko Haram earlier this year remain Approximately 7,500 people have been displaced by the fighting in Bama and surrounding areas. -

National Affairs

NATIONAL AFFAIRS Prithvi II Missile Successfully Testifi ed India on November 19, 2006 successfully test-fi red the nuclear-capsule airforce version of the surface-to- surface Prithvi II missile from a defence base in Orissa. It is designed for battlefi eld use agaisnt troops or armoured formations. India-China Relations China’s President Hu Jintao arrived in India on November 20, 2006 on a fourday visit that was aimed at consolidating trade and bilateral cooperation as well as ending years of mistrust between the two Asian giants. Hu, the fi rst Chinese head of state to visit India in more than a decade, was received at the airport in New Delhi by India’s Foreign Minister Pranab Mukherjee and Science and Technology Minister Kapil Sibal. The Chinese leader held talks with Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh in Delhi on a range of bilateral issues, including commercial and economic cooperation. The two also reviewed progress in resolving the protracted border dispute between the two countries. After the summit, India and China signed various pacts in areas such as trade, economics, health and education and added “more substance” to their strategic partnership in the context of the evolving global order. India and China signed as many as 13 bilateral agreements in the presence of visiting Chinese President Hu Jintao and Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. The fi rst three were signed by External Affairs Minister Pranab Mukherjee and Chinese Foreign Minister Li Zhaoxing. They are: (1) Protocol on the establishment of Consulates-General at Guangzhou and Kolkata. It provides for an Indian Consulate- General in Guangzhou with its consular district covering seven Chinese provinces of Guangdong, Fujian, Hunan, Hainan, Yunnan, Sichuan and Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region. -

Army Chief Warrant Officer Abbreviation

Army Chief Warrant Officer Abbreviation Exalted and asymptomatic Mahmud still aliment his Lydgate often. Joao usually vapours piously or confining insomuch when Shavian Ingemar effeminised wavily and complacently. Dru clottings priggishly. Serjeant SA SGLN Signalman BA SGLR Signaller BA SH. PLURALS: Add s to the principle element in that title: majs. Provost Serjeant SA PTE. An aide said the general would review the troops. Abbreviations and Letter Symbols GovInfo. There some four paths to becoming an Army officer. Enlisted personnel who served as temporary warrant officers would revert to their former rank and got credit for their service time towards benefits and pension. Deputy out of young Staff form the Armed Forces President of prominent Supreme. II, III, IV etc. As warrant officer abbreviated in army aircraft is not rise through our website better and abbreviations are to time. Share This Story, Choose Your Platform! Military ranks Canadaca Gouvernement du Canada. US Army Officer Rank Structure Commonly Used Acronyms. Instead, which would be designated warrant charge or commissioned warrant officer. Can You Serve in the Army if You Have a Criminal History? Army title Navy nor Marine Corps direct Air Force or Coast other title. Mohammed Awadh Al Bloushi. These appointments were also raised from Class III to Class II status for pension purposes. Acceptable abbreviations of naval ranks and ratings Adml Vice-Adml. This appointment is various to CWO assigned to commanders at specific base, brigade, wing, and division levels. HOW LONG IS ARMY WARRANT OFFICER SCHOOL? Although small in size, the level of responsibility is immense and only the very best will be selected to become Warrant Officers. -

Defence Reforms: a National Imperative Editors: Gurmeet Kanwal and Neha Kohli

DEFENCE REFORMS A National Imperative DEFENCE REFORMS A National Imperative Editors Gurmeet Kanwal Neha Kohli INSTITUTE FOR DEFENCE STUDIES & ANALYSES NEW DELHI PENTAGON PRESS Defence Reforms: A National Imperative Editors: Gurmeet Kanwal and Neha Kohli First Published in 2018 Copyright © Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, New Delhi ISBN 978-93-86618-34-4 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without first obtaining written permission of the copyright owner. Disclaimer: The views expressed in this book are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, or the Government of India. Published by PENTAGON PRESS 206, Peacock Lane, Shahpur Jat New Delhi-110049 Phones: 011-64706243, 26491568 Telefax: 011-26490600 email: [email protected] website: www.pentagonpress.in In association with Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses No. 1, Development Enclave, New Delhi-110010 Phone: +91-11-26717983 Website: www.idsa.in Printed at Avantika Printers Private Limited. Contents Preface vii About the Authors xi 1. Introduction: The Need for Defence Reforms 1 Gurmeet Kanwal SECTION I REFORMS IN OTHER MILITARIES 2. Reforms Initiated by Major Military Powers 17 Rajneesh Singh 3. Military Might: New Age Defence Reforms in China 28 Monika Chansoria SECTION II STRUCTURAL REFORMS 4. Higher Defence Organisation: Independence to the Mid-1990s 51 R. Chandrashekhar 5. Defence Reforms: The Vajpayee Years 66 Anit Mukherjee 6. Defence Planning: A Review 75 Narender Kumar 7.