Development of Operational Thinking in the German Army in the World War Era

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pr-Dvd-Holdings-As-Of-September-18

CALL # LOCATION TITLE AUTHOR BINGE BOX COMEDIES prmnd Comedies binge box (includes Airplane! --Ferris Bueller's Day Off --The First Wives Club --Happy Gilmore)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX CONCERTS AND MUSICIANSprmnd Concerts and musicians binge box (Includes Brad Paisley: Life Amplified Live Tour, Live from WV --Close to You: Remembering the Carpenters --John Sebastian Presents Folk Rewind: My Music --Roy Orbison and Friends: Black and White Night)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX MUSICALS prmnd Musicals binge box (includes Mamma Mia! --Moulin Rouge --Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella [DVD] --West Side Story) [videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX ROMANTIC COMEDIESprmnd Romantic comedies binge box (includes Hitch --P.S. I Love You --The Wedding Date --While You Were Sleeping)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. DVD 001.942 ALI DISC 1-3 prmdv Aliens, abductions & extraordinary sightings [videorecording]. DVD 001.942 BES prmdv Best of ancient aliens [videorecording] / A&E Television Networks History executive producer, Kevin Burns. DVD 004.09 CRE prmdv The creation of the computer [videorecording] / executive producer, Bob Jaffe written and produced by Donald Sellers created by Bruce Nash History channel executive producers, Charlie Maday, Gerald W. Abrams Jaffe Productions Hearst Entertainment Television in association with the History Channel. DVD 133.3 UNE DISC 1-2 prmdv The unexplained [videorecording] / produced by Towers Productions, Inc. for A&E Network executive producer, Michael Cascio. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again [videorecording] / producers, Simon Harries [and three others] director, Ashok Prasad [and five others]. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again. Season 2 [videorecording] / director, Luc Tremoulet producer, Page Shepherd. -

Axis Blitzkrieg: Warsaw and Battle of Britain

Axis Blitzkrieg: Warsaw and Battle of Britain By Skyla Gabriel and Hannah Seidl Background on Axis Blitzkrieg ● A military strategy specifically designed to create disorganization in enemy forces by logical firepower and mobility of forces ● Limits civilian casualty and waste of fire power ● Developed in Germany 1918-1939 as a result of WW1 ● Used in Warsaw, Poland in 1939, then with eventually used in Belgium, the Netherlands, North Africa, and even against the Soviet Union Hitler’s Plan and “The Night Before” ● Due to the non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union, once the Polish state was divided up, Hitler would colonize the territory and only allow the “superior race” to live there and would enslave the natives. ● On August 31, 1939 Hitler ordered Nazi S.S. troops,wearing Polish officer uniforms, to sneak into Poland. ● The troops did minor damage to buildings and equipment. ● Left dead concentration camp prisoners in Polish uniforms ● This was meant to mar the start of the Polish Invasion when the bodies were found in the morning by Polish officers Initial stages ● Initially, one of Hitler’s first acts after coming to power was to sign a nonaggression pact (January 1934) with Poland in order to avoid a French- Polish alliance before Germany could rearm. ● Through 1935- March 1939 Germany slowly gained more power through rearmament (agreed to by both France and Britain), Germany then gained back the Rhineland through militarization, annexation of Austria, and finally at the Munich Conference they were given the Sudetenland. ● Once Czechoslovakia was dismembered Britain and France responded by essentially backing Poland and Hitler responded by signing a non-aggression with the Soviet Union in the summer of 1939 ● The German-Soviet pact agreed Poland be split between the two powers, the new pact allowed Germany to attack Poland without fear of Soviet intervention The Attack ● On September 1st, 1939 Germany invaded Warsaw, Poland ● Schleswig-Holstein, a German Battleship at 4:45am began to fire on the Polish garrison in Westerplatte Fort, Danzig. -

Decision-Making Process in Combat Operations

DECISION-MAKING PROCESS IN MILITARY COMBAT OPERATIONS 4120/002 10.2013 2000 10.2013 4120/002 International Committee of the Red Cross 19, avenue de la Paix 1202 Geneva, Switzerland T +41 22 734 60 01 F +41 22 733 20 57 E-mail: [email protected] www.icrc.org © ICRC, October 2013 DECISION-MAKING PROCESS IN MILITARY COMBAT OPERATIONS PREFACE Every state has an obligation to ensure respect for the law of armed conflict. The ICRC is mandated to support states in these efforts and does so through a range of activities, including promoting the integration of appropriate com- pliance measures into military doctrine, education, training and sanctions, with a view to ensuring that behaviours of those engaged in armed conflict comply with the law. The present note is designed to support the integration of the Law of Armed Conflict into military decision-making processes, primarily at the operational level. It is not based on any specific national doctrine. It is designed to support those responsible for developing national doctrine and operational planning procedures in their efforts to integrate the Law of Armed Conflict into military practice. The desired outcome is staff procedures which ensure the development of military plans and orders that accurately and effectively integrate compliance with the Law of Armed Conflict into operational practice, thereby reducing the effects of armed conflict on those who do not, or no longer, participate in the hostilities. The techniques of warfare change rapidly, particularly at times when combat operations are commonplace. The humanitarian impact of conflict is timeless. The Law of Armed Conflict is designed to limit the humanitarian consequences of war. -

Blitzkrieg: the Evolution of Modern Warfare and the Wehrmacht's

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 8-2021 Blitzkrieg: The Evolution of Modern Warfare and the Wehrmacht’s Impact on American Military Doctrine during the Cold War Era Briggs Evans East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Evans, Briggs, "Blitzkrieg: The Evolution of Modern Warfare and the Wehrmacht’s Impact on American Military Doctrine during the Cold War Era" (2021). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3927. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/3927 This Thesis - unrestricted is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Blitzkrieg: The Evolution of Modern Warfare and the Wehrmacht’s Impact on American Military Doctrine during the Cold War Era ________________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History ______________________ by Briggs Evans August 2021 _____________________ Dr. Stephen Fritz, Chair Dr. Henry Antkiewicz Dr. Steve Nash Keywords: Blitzkrieg, doctrine, operational warfare, American military, Wehrmacht, Luftwaffe, World War II, Cold War, Soviet Union, Operation Desert Storm, AirLand Battle, Combined Arms Theory, mobile warfare, maneuver warfare. ABSTRACT Blitzkrieg: The Evolution of Modern Warfare and the Wehrmacht’s Impact on American Military Doctrine during the Cold War Era by Briggs Evans The evolution of United States military doctrine was heavily influenced by the Wehrmacht and their early Blitzkrieg campaigns during World War II. -

To Examine the Horrors of Trench Warfare

TRENCH WARFARE Objective: To examine the horrors of trench warfare. What problems faced attacking troops? What was Trench Warfare? Trench Warfare was a type of fighting during World War I in which both sides dug trenches that were protected by mines and barbed wire Cross-section of a front-line trench How extensive were the trenches? An aerial photograph of the opposing trenches and no-man's land in Artois, France, July 22, 1917. German trenches are at the right and bottom, British trenches are at the top left. The vertical line to the left of centre indicates the course of a pre-war road. What was life like in the trenches? British trench, France, July 1916 (during the Battle of the Somme) What was life like in the trenches? French soldiers firing over their own dead What were trench rats? Many men killed in the trenches were buried almost where they fell. These corpses, as well as the food scraps that littered the trenches, attracted rats. Quotes from soldiers fighting in the trenches: "The rats were huge. They were so big they would eat a wounded man if he couldn't defend himself." "I saw some rats running from under the dead men's greatcoats, enormous rats, fat with human flesh. My heart pounded as we edged towards one of the bodies. His helmet had rolled off. The man displayed a grimacing face, stripped of flesh; the skull bare, the eyes devoured and from the yawning mouth leapt a rat." What other problems did soldiers face in the trenches? Officers walking through a flooded communication trench. -

The Other Side of the Monument: Memory, Preservation, and the Battles of Franklin and Nashville

THE OTHER SIDE OF THE MONUMENT: MEMORY, PRESERVATION, AND THE BATTLES OF FRANKLIN AND NASHVILLE by JOE R. BAILEY B.S., Austin Peay State University, 2006 M.A., Austin Peay State University, 2008 AN ABSTRACT OF A DISSERTATION submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2015 Abstract The thriving areas of development around the cities of Franklin and Nashville in Tennessee bear little evidence of the large battles that took place there during November and December, 1864. Pointing to modern development to explain the failed preservation of those battlefields, however, radically oversimplifies how those battlefields became relatively obscure. Instead, the major factor contributing to the lack of preservation of the Franklin and Nashville battlefields was a fractured collective memory of the two events; there was no unified narrative of the battles. For an extended period after the war, there was little effort to remember the Tennessee Campaign. Local citizens and veterans of the battles simply wanted to forget the horrific battles that haunted their memories. Furthermore, the United States government was not interested in saving the battlefields at Franklin and Nashville. Federal authorities, including the War Department and Congress, had grown tired of funding battlefields as national parks and could not be convinced that the two battlefields were worthy of preservation. Moreover, Southerners and Northerners remembered Franklin and Nashville in different ways, and historians mainly stressed Eastern Theater battles, failing to assign much significance to Franklin and Nashville. Throughout the 20th century, infrastructure development encroached on the battlefields and they continued to fade from public memory. -

Interaction and Perception in Anglo-German Armies: 1689-1815

Interaction and Perception in Anglo-German Armies: 1689-1815 Mark Wishon Ph.D. Thesis, 2011 Department of History University College London Gower Street London 1 I, Mark Wishon confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 ABSTRACT Throughout the ‘long eighteenth century’ Britain was heavily reliant upon soldiers from states within the Holy Roman Empire to augment British forces during times of war, especially in the repeated conflicts with Bourbon, Revolutionary, and Napoleonic France. The disparity in populations between these two rival powers, and the British public’s reluctance to maintain a large standing army, made this external source of manpower of crucial importance. Whereas the majority of these forces were acting in the capacity of allies, ‘auxiliary’ forces were hired as well, and from the mid-century onwards, a small but steadily increasing number of German men would serve within British regiments or distinct formations referred to as ‘Foreign Corps’. Employing or allying with these troops would result in these Anglo- German armies operating not only on the European continent but in the American Colonies, Caribbean and within the British Isles as well. Within these multinational coalitions, soldiers would encounter and interact with one another in a variety of professional and informal venues, and many participants recorded their opinions of these foreign ‘brother-soldiers’ in journals, private correspondence, or memoirs. These commentaries are an invaluable source for understanding how individual Briton’s viewed some of their most valued and consistent allies – discussions that are just as insightful as comparisons made with their French enemies. -

The Decisive Battles of World History Course Guidebook

Topic Subtopic History Military The Decisive Battles of World History Course Guidebook Professor Gregory S. Aldrete Uniiversityy of WWisconsin–Green Bay PUBLISHED BY: THE GREAT COURSES Corporate Headquarters 4840 Westfields Boulevard, Suite 500 Chantilly, Virginia 20151-2299 Phone: 1-800-832-2412 Fax: 703-378-3819 www.thegreatcourses.com Copyright © The Teaching Company, 2014 Printed in the United States of America This book is in copyright. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of The Teaching Company. Gregory S. Aldrete, Ph.D. Frankenthal Professor of History and Humanistic Studies University of Wisconsin–Green Bay rofessor Gregory S. Aldrete is the Frankenthal Professor of History and Humanistic Studies Pat the University of Wisconsin–Green Bay. He received his B.A. from Princeton University in 1988 and his Ph.D. from the University of Michigan in 1995. His interdisciplinary scholarship spans the ¿HOGVRIKLVWRU\DUFKDHRORJ\DUWKLVWRU\PLOLWDU\KLVWRU\DQGSKLORORJ\ Among the books Professor Aldrete has written or edited are Gestures and Acclamations in Ancient Rome; Floods of the Tiber in Ancient Rome; Daily Life in the Roman City: Rome, Pompeii, and Ostia; The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Daily Life: A Tour through History from Ancient Times to the Present, volume 1, The Ancient World; The Long Shadow of Antiquity: What Have the Greeks and Romans Done for Us? (with Alicia Aldrete); and Reconstructing Ancient Linen Body Armor: Unraveling the Linothorax Mystery (with Scott Bartell and Alicia Aldrete). -

Fighting Patton Photographs

Fighting Patton Photographs [A]Mexican Punitive Expedition pershing-villa-obregon.tif: Patton’s first mortal enemy was the commander of Francisco “Pancho” Villa’s bodyguard during the Mexican Punitive Expedition. Left to right: General Álvaro Obregón, Villa, Brig. Gen. John Pershing, Capt. George Patton. [A]World War I Patton_France_1918.tif: Col. George Patton with one of his 1st Tank Brigade FT17s in France in 1918. Diepenbroick-Grüter_Otto Eitel_Friedrich.tif: Prince Freiherr von.tif: Otto Freiherr Friedrich Eitel commanded the von Diepenbroick-Grüter, 1st Guards Division in the pictured as a cadet in 1872, Argonnes. commanded the 10th Infantry Division at St. Mihiel. Gallwitz_Max von.tif: General Wilhelm_Crown Prince.tif: Crown der Artillerie Max von Prince Wilhelm commanded the Gallwitz’s army group defended region opposite the Americans. the St. Mihiel salient. [A]Morocco and Vichy France Patton_Hewitt.tif: Patton and Rear Admiral Henry Kent Hewitt, commanding Western Naval Task Force, aboard the Augusta before invading Vichy-controlled Morocco in Operation Torch. NoguesLascroux: Arriving at Fedala to negotiate an armistice at 1400 on 11 November 1942, Gen. Charles Noguès (left) is met by Col. Hobart Gay. Major General Auguste Lahoulle, Commander of French Air Forces in Morocco, is on the right. Major General Georges Lascroux, Commander in Chief of Moroccan troops, carries a briefcase. Noguès_Charles.tif: Charles Petit_Jean.tif: Jean Petit, Noguès, was Vichy commander- commanded the garrison at in-chief in Morocco. Port Lyautey. (Courtesy of Stéphane Petit) [A]The Axis Powers Patton_Monty.tif: Patton and his rival Gen. Bernard Montgomery greet each other on Sicily in July 1943. The two fought the Axis powers in Tunisia, Sicily, and the European theater. -

American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics

American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics Updated July 29, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL32492 American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics Summary This report provides U.S. war casualty statistics. It includes data tables containing the number of casualties among American military personnel who served in principal wars and combat operations from 1775 to the present. It also includes data on those wounded in action and information such as race and ethnicity, gender, branch of service, and cause of death. The tables are compiled from various Department of Defense (DOD) sources. Wars covered include the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, the Mexican War, the Civil War, the Spanish-American War, World War I, World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam Conflict, and the Persian Gulf War. Military operations covered include the Iranian Hostage Rescue Mission; Lebanon Peacekeeping; Urgent Fury in Grenada; Just Cause in Panama; Desert Shield and Desert Storm; Restore Hope in Somalia; Uphold Democracy in Haiti; Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF); Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF); Operation New Dawn (OND); Operation Inherent Resolve (OIR); and Operation Freedom’s Sentinel (OFS). Starting with the Korean War and the more recent conflicts, this report includes additional detailed information on types of casualties and, when available, demographics. It also cites a number of resources for further information, including sources of historical statistics on active duty military deaths, published lists of military personnel killed in combat actions, data on demographic indicators among U.S. military personnel, related websites, and relevant CRS reports. Congressional Research Service American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................... -

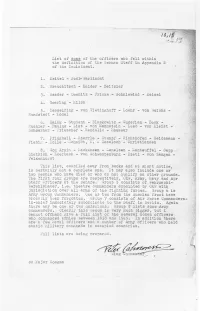

List of Some of the Officers ~~10 Fall Within the Definition of the German

-------;-:-~---,-..;-..............- ........- List of s ome of t he officers ~~10 fall within t he de finition of t he German St af f . in Appendix B· of t he I n cii c tment . 1 . Kei t e l - J odl- Aar l imont 2 . Br auchi t s ch - Halder - Zei t zl er 3. riaeder - Doeni t z - Fr i cke - Schni ewi nd - Mei s el 4. Goer i ng - fu i l ch 5. Kes s el r i ng ~ von Vi et i nghof f - Loehr - von ~e i c h s rtun c1 s t ec t ,.. l.io d eL 6. Bal ck - St ude nt - Bl a skowi t z - Gud er i an - Bock Kuchl er - Pa ul us - Li s t - von Manns t ei n - Leeb - von Kl e i ~ t Schoer ner - Fr i es sner - Rendul i c - Haus s er 7. Pf l ug bei l - Sper r l e - St umpf - Ri cht hof en - Sei a emann Fi ebi £; - Eol l e - f)chmi dt , E .- Des s l och - .Christiansen 8 . Von Arni m - Le ck e ris en - :"emelsen - l.~ a n t e u f f e l - Se pp . J i et i i ch - 1 ber ba ch - von Schweppenburg - Di e t l - von Zang en t'al kenhol's t rr hi s' list , c ompiled a way f r om books and a t. shor t notice, is c ertai nly not a complete one . It may also include one or t .wo neop .le who have ai ed or who do not q ual ify on other gr ounds . -

Assessing the Implications of Possible Changes to Women in Service Restrictions: Practices of Foreign Militaries and Other Organizations

Assessing the Implications of Possible Changes to Women in Service Restrictions: Practices of Foreign Militaries and Other Organizations Annemarie Randazzo-Matsel • Jennifer Schulte • Jennifer Yopp DIM-2012-U-000689-Final July 2012 Photo credit line: Young Israeli women undergo tough, initial pre-army training at Zikim Army Base in southern Israel. REUTERS/Nir Elias Approved for distribution: July 2012 Anita Hattiangadi Research Team Leader Marine Corps Manpower Team Resource Analysis Division This document represents the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the Department of the Navy. Cleared for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited. Specific authority: N00014-11-D-0323. Copies of this document can be obtained through the CNA Document Control and Distribution Section at 703-824-2123. Copyright 2012 CNA This work was created in the performance of Federal Government Contract Number N00014-11-D-0323. Any copyright in this work is subject to the Government's Unlimited Rights license as defined in DFARS 252.227-7013 and/or DFARS 252.227-7014. The reproduction of this work for commercial purposes is strictly prohibited. Nongovernmental users may copy and distribute this document in any medium, either commercially or noncommercially, provided that this copyright notice is reproduced in all copies. Nongovernmental users may not use technical measures to obstruct or control the read-ing or further copying of the copies they make or distribute. Nongovernmental users may not accept compensation of any manner in exchange for copies. All other rights reserved. Contents Executive summary . 1 Foreign militaries . 3 Australia . 4 ADF composition .