Defence Reforms: a National Imperative Editors: Gurmeet Kanwal and Neha Kohli

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces

European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 SUPPORT IS OUR MISSION European Asylum Support Office Afghanistan State Structure and Security Forces Country of Origin Information Report August 2020 More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). ISBN: 978-92-9485-650-0 doi: 10.2847/115002 BZ-02-20-565-EN-N © European Asylum Support Office (EASO) 2020 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, unless otherwise stated. For third-party materials reproduced in this publication, reference is made to the copyrights statements of the respective third parties. Cover photo: © Al Jazeera English, Helmand, Afghanistan 3 November 2012, url CC BY-SA 2.0 Taliban On the Doorstep: Afghan soldiers from 215 Corps take aim at Taliban insurgents. 4 — AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY FORCES - EASO COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT Acknowledgements This report was drafted by the European Asylum Support Office COI Sector. The following national asylum and migration department contributed by reviewing this report: The Netherlands, Office for Country Information and Language Analysis, Ministry of Justice It must be noted that the review carried out by the mentioned departments, experts or organisations contributes to the overall quality of the report, it but does not necessarily imply their formal endorsement of the final report, which is the full responsibility of EASO. AFGHANISTAN: STATE STRUCTURE AND SECURITY -

Smart Border Management: Indian Coastal and Maritime Security

Contents Foreword p2/ Preface p3/ Overview p4/ Current initiatives p12/ Challenges and way forward p25/ International examples p28/Sources p32/ Glossary p36/ FICCI Security Department p38 Smart border management: Indian coastal and maritime security September 2017 www.pwc.in Dr Sanjaya Baru Secretary General Foreword 1 FICCI India’s long coastline presents a variety of security challenges including illegal landing of arms and explosives at isolated spots on the coast, infiltration/ex-filtration of anti-national elements, use of the sea and off shore islands for criminal activities, and smuggling of consumer and intermediate goods through sea routes. Absence of physical barriers on the coast and presence of vital industrial and defence installations near the coast also enhance the vulnerability of the coasts to illegal cross-border activities. In addition, the Indian Ocean Region is of strategic importance to India’s security. A substantial part of India’s external trade and energy supplies pass through this region. The security of India’s island territories, in particular, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, remains an important priority. Drug trafficking, sea-piracy and other clandestine activities such as gun running are emerging as new challenges to security management in the Indian Ocean region. FICCI believes that industry has the technological capability to implement border management solutions. The government could consider exploring integrated solutions provided by industry for strengthening coastal security of the country. The FICCI-PwC report on ‘Smart border management: Indian coastal and maritime security’ highlights the initiatives being taken by the Central and state governments to strengthen coastal security measures in the country. -

Battle of Hajipir (Indo-Pak War 1965)

No. 08/2019 AN INDIAN ARMY PUBLICATION August 2019 BATTLE OF HAJIPIR (INDO-PAK WAR 1965) MAJOR RANJIT SINGH DAYAL, PVSM, MVC akistan’s forcible attempt to annex Kashmir was defeated when India, even though surprised by the Pakistani offensive, responded with extraordinary zeal and turned the tide in a war, Pakistan thought it would win. Assuming discontent in Kashmir with India, Pakistan sent infiltrators to precipitate Pinsurgency against India under ‘OPERATION GIBRALTAR’, followed by the plan to capture Akhnoor under ‘OPERATION GRAND SLAM’. The Indian reaction was swift and concluded with the epic capture of the strategic Haji Pir Pass, located at a height of 2637 meters on the formidable PirPanjal Range, that divided the Kashmir Valley from Jammu. A company of 1 PARA led by Major (later Lieutenant General) Ranjit Singh Dayal wrested control of Haji Pir Pass in Jammu & Kashmir, which was under the Pakistani occupation. The initial victory came after a 37- hour pitched battle by the stubbornly brave and resilient troops. Major Dayal and his company accompanied by an Artillery officer started at 1400 hours on 27 August. As they descended into the valley, they were subjected to fire from the Western shoulder of the pass. There were minor skirmishes with the enemy, withdrawing from Sank. Towards the evening, torrential rains covered the mountain with thick mist. This made movement and direction keeping difficult. The men were exhausted after being in the thick of battle for almost two days. But Major Dayal urged them to move on. On reaching the base of the pass, he decided to leave the track and climb straight up to surprise the enemy. -

Border Security Force Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India

Border Security Force Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India RECRUITMENT OF MERITORIOUS SPORTSPERSONS TO THE POST OF CONSTABLE (GENERAL DUTY) UNDER SPORTS QUOTA 2020-21 IN BORDER SECURITY FORCE Application are invited from eligible Indian citizen (Male & Female) for filling up 269 vacancies for the Non- Gazetted & Non Ministerial post of Constable(General Duty) in Group “C” on temporary basis likely to be made permanent in Border Security Force against Sports quota as per table at Para 2(a). Application from candidate will be accepted through ON-LINE MODE only. No other mode for submission is allowed. ONLINE APPLICATION MODE WILL BE OPENED W.E.F.09/08/2021 AT 00:01 AM AND WILL BE CLOSED ON 22/09/2021 AT 11:59 PM. 2. Vacancies :- a) There are 269 vacancies in the following Sports/Games disciplines :- S/No. Name of Team Vac Nos of events/weight category 1 Boxing(Men) 49 Kg-2 52 Kg-1 56 Kg-1 60 Kg-1 10 64 Kg-1 69 Kg-1 75 Kg-1 81 Kg-1 91 + Kg-1 Boxing(Women) 10 48 Kg-1 51 Kg-1 54 Kg-1 57 Kg-1 60 Kg-1 64 Kg-1 69 Kg-1 71 Kg-1 81 Kg-1 81 + Kg-1 2 Judo(Men) 08 60 Kg-1 66 Kg-1 73 Kg-1 81 Kg-2 90 Kg-1 100 Kg-1 100 + Kg-1 Judo(Women) 08 48 Kg-1 52 Kg-1 57 Kg-1 63 Kg-1 70 Kg-1 78 Kg-1 78 + Kg-2 3 Swimming(Men) 12 Swimming Indvl Medley -1 Back stroke -1 Breast stroke -1 Butterfly Stroke -1 Free Style -1 Water polo Player-3 Golkeeper-1 Diving Spring/High board-3 Swimming(Women) 04 Water polo Player-3 Diving Spring/High board-1 4 Cross Country (Men) 02 10 KM-2 Cross Country(Women) 02 10 KM -2 5 Kabaddi (Men) 10 Raider-3 All-rounder-3 Left Corner-1 Right Corner1 Left Cover -1 Right Cover-1 6 Water Sports(Men) 10 Left-hand Canoeing-4 Right-hand Canoeing -2 Rowing -1 Kayaking -3 Water Sports(Women) 06 Canoeing -3 Kayaking -3 7 Wushu(Men) 11 48 Kg-1 52 Kg-1 56 Kg-1 60 Kg-1 65 Kg-1 70 Kg-1 75 Kg-1 80 Kg-1 85 Kg-1 90 Kg-1 90 + Kg-1 8 Gymnastics (Men) 08 All-rounder -2 Horizontal bar-2 Pommel-2 Rings-2 9 Hockey(Men) 08 Golkeeper1 Forward Attacker-2 Midfielder-3 Central Full Back-2 10 Weight Lifting(Men) 08 55 Kg-1 61 Kg-1 67 Kg-1 73 Kg-1 81 Kg-1 89 Kg-1 96 Kg-1 109 + Kg-1 Wt. -

Failed State Wars

Afghanistan: A War in Crisis! Anthony H. Cordesman September 10, 2019 Working draft, Please send comments and suggested additions to [email protected] Picture: SHAH MARAI/AFP/Getty Images Introduction The war in Afghanistan is at a critical stage. There is no clear end in sight that will result in a U.S. military victory or in the creation of a stable Afghan state. A peace settlement may be possible, but so far, this only seems possible on terms sufficiently favorable to the Taliban so that such peace may become an extension of war by other means and allow the Taliban to exploit such a settlement to the point where it comes to control large parts of the country. The ongoing U.S. peace effort is a highly uncertain option. There are no official descriptions of the terms of the peace that the Administration is now seeking to negotiate, but media reports indicate that it may be considering significant near-term U.S. force cuts, and a full withdrawal within one to two years of any settlement. Media reports indicate that the Administration is considering a roughly 50% cut in the total number of U.S. military personnel now deployed in Afghanistan — even if a peace is not negotiated. No plans have been advanced to guarantee a peace settlement, disarm part or all of the force on either side, provide any form of peace keeping forces, or provide levels of civil and security aid that would give all sides an incentive to cooperate and help stabilize the country. The Taliban has continued to reject formal peace negotiations with the Afghan government, and has steadily stepped up its military activity and acts of violence while it negotiates with the United States. -

List of Some of the Officers ~~10 Fall Within the Definition of the German

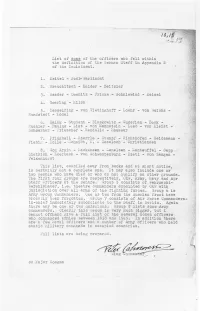

-------;-:-~---,-..;-..............- ........- List of s ome of t he officers ~~10 fall within t he de finition of t he German St af f . in Appendix B· of t he I n cii c tment . 1 . Kei t e l - J odl- Aar l imont 2 . Br auchi t s ch - Halder - Zei t zl er 3. riaeder - Doeni t z - Fr i cke - Schni ewi nd - Mei s el 4. Goer i ng - fu i l ch 5. Kes s el r i ng ~ von Vi et i nghof f - Loehr - von ~e i c h s rtun c1 s t ec t ,.. l.io d eL 6. Bal ck - St ude nt - Bl a skowi t z - Gud er i an - Bock Kuchl er - Pa ul us - Li s t - von Manns t ei n - Leeb - von Kl e i ~ t Schoer ner - Fr i es sner - Rendul i c - Haus s er 7. Pf l ug bei l - Sper r l e - St umpf - Ri cht hof en - Sei a emann Fi ebi £; - Eol l e - f)chmi dt , E .- Des s l och - .Christiansen 8 . Von Arni m - Le ck e ris en - :"emelsen - l.~ a n t e u f f e l - Se pp . J i et i i ch - 1 ber ba ch - von Schweppenburg - Di e t l - von Zang en t'al kenhol's t rr hi s' list , c ompiled a way f r om books and a t. shor t notice, is c ertai nly not a complete one . It may also include one or t .wo neop .le who have ai ed or who do not q ual ify on other gr ounds . -

Assessing the Implications of Possible Changes to Women in Service Restrictions: Practices of Foreign Militaries and Other Organizations

Assessing the Implications of Possible Changes to Women in Service Restrictions: Practices of Foreign Militaries and Other Organizations Annemarie Randazzo-Matsel • Jennifer Schulte • Jennifer Yopp DIM-2012-U-000689-Final July 2012 Photo credit line: Young Israeli women undergo tough, initial pre-army training at Zikim Army Base in southern Israel. REUTERS/Nir Elias Approved for distribution: July 2012 Anita Hattiangadi Research Team Leader Marine Corps Manpower Team Resource Analysis Division This document represents the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the Department of the Navy. Cleared for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited. Specific authority: N00014-11-D-0323. Copies of this document can be obtained through the CNA Document Control and Distribution Section at 703-824-2123. Copyright 2012 CNA This work was created in the performance of Federal Government Contract Number N00014-11-D-0323. Any copyright in this work is subject to the Government's Unlimited Rights license as defined in DFARS 252.227-7013 and/or DFARS 252.227-7014. The reproduction of this work for commercial purposes is strictly prohibited. Nongovernmental users may copy and distribute this document in any medium, either commercially or noncommercially, provided that this copyright notice is reproduced in all copies. Nongovernmental users may not use technical measures to obstruct or control the read-ing or further copying of the copies they make or distribute. Nongovernmental users may not accept compensation of any manner in exchange for copies. All other rights reserved. Contents Executive summary . 1 Foreign militaries . 3 Australia . 4 ADF composition . -

In This Issue... Plus

Volume 18 No. 2 February 2009 12 in this issue... 6 Vibrant Gujarat 8 India Inc. at Davos 12 15th Partnership Summit 22 3rd Sustainability Summit 8 31 Defence Industry Seminar plus... n India Rubber Expo 2009 n The Power of Cause & Effect n India’s Tryst with Corporate Governance 22 n India & the World n Regional Round Up n And all our regular features We welcome your feedback and suggestions. Do write to us at 31 [email protected] Edited, printed and published by Director General, CII on behalf of Confederation of Indian Industry from The Mantosh Sondhi Centre, 23, Institutional Area, Lodi Road, New Delhi-110003 Tel: 91-11-24629994-7 Fax: 91-11-24626149 Email: [email protected] Website: www.cii.in Printed at Aegean Offset Printers F-17 Mayapuri Industrial Area, Phase II, New Delhi-110064 Registration No. 34541/79 JOURNAL OF THE Confederation OF INDIAN INDUSTRY 2 | February 2009 Communiqué Padma Vibhushan award winner Ashok S Ganguly Member, Prime Minister’s Council on Trade & Industry, Member India USA CEO Council, Member, Investment Commission, and Member, National Knowledge Commission Padma Bhushan award winners Shekhar Gupta A M Naik Sam Pitroda C K Prahalad Editor-in-Chief, Indian Chairman and Chairman, National Paul and Ruth McCracken Express Newspapers Managing Director, Knowledge Commission Distinguished University (Mumbai) Ltd. Larsen & Toubro Professor of Strategy Padma Shri award winner R K Krishnakumar Director, Tata Sons, Chairman, Tata Coffee & Asian Coffee, and Vice-Chairman, Tata Tea & Indian Hotels Communiqué February 2009 | 5 newsmaker event 4th Biennial Global Narendra Modi, Chief Minister, Gujarat, Mukesh Ambani, Chairman, Investors’ Summit 2009 Reliance Industries, Ratan Tata, Chairman, Tata Group, K V Kamath, President, CII, and Raila Amolo Odinga, Prime Minister, Kenya ibrant Gujarat, the 4th biennial Global Investors’ and Mr Ajit Gulabchand, Chairman & Managing Director, Summit 2009 brought together business leaders, Hindustan Construction Company Ltd, among several investors, corporations, thought leaders, policy other dignitaries. -

The Civil Challenges to Peace in Afghanistan

The Civil Challenges to Peace in Afghanistan September 10, 2019 Anthony H. Cordesman With the assistance of Max Molot Working draft, Please send comments and suggested additions to [email protected] Picture: WAKIL KOHSAR/AFP/Getty Images The Failed Civil Side of the War Far too much of the current discussion of the peace process in Afghanistan focuses on whether a peace agreement can be negotiated, and not on whether a peace can be successfully enforced and a stable state emerge out of the peace process. Previous reporting by the Burke Chair has raised serious questions about the ability of the Afghan security forces to secure a peace without continued support from U.S. combat forces. This report addresses a different set of issues. It addresses a critical aspect of the current peace process: its apparent failure to focus on creating a stable post conflict state. It shows that the Afghan government faces a a set of civil challenges which are as serious as the challenges of creating a functioning peace with the Taliban. It does not focus, however, on the current political challenge and divisions within the Afghan Government that are shaping the coming election. It instead examines Afghan popular perceptions of the current level of governance, the deep structural challenges that the Afghan government will have to confront in order to govern effectively in the face of challenges from the Taliban and other opposition groups, and the government’s dependence on continued levels of massive outside aid. It examines the current levels of poverty and economic stress that the government will face even if the fighting ends, and the kind of pressure that a rapidly growing civil population will put on the government for new jobs and higher living standards once the fighting ceases. -

India's Higher Defence Organisation

India’s Higher Defence Organisation: Implications for National Security and Jointness Arun Prakash INTRODUCTION In the minds of the average person on the street, one suspects that the phrase “higher defence organization” evokes an intimidating vision of row upon row of be-medalled and be-whiskered Generals, with the dark shadowy figure of a “soldier on horseback” (that mythical usurper of power) looming in the background. Too complex and dreadful to contemplate, they shut this vision out of their minds, and revert to the mundane, with which they feel far more comfortable. It is for this specific reason that in the title of this paper “National Security” has been added to “Higher Defence Organization.” Not that our comprehension of “National Security” is very much better; and in this context, just one example will suffice. Soon after the July 2006 serial train blasts in Mumbai, which resulted in over 200 dead and over 700 injured, as Chief of Naval Staff (CNS), I attended a very high level inter-agency meeting of functionaries to discuss this issue. After the presentations, discussions and brain-storming lasting a couple of hours, a final question was asked -- what urgent remedial and precautionary measures should we take to prevent recurrence of such incidents? After a pregnant silence, the sole suggestion that was voiced, shook me to the core, because of the pedestrian and worm’s eye perspective that it demonstrated: “We must give the SHOs at the thana level more and better quality walkie-talkie sets to ensure faster communications.” And this, after the nation has been experiencing bomb blasts or terrorist attacks with monotonous regularity in the wake of the horrifying 1993 Mumbai carnage; Parliament (2001), Akshardham (2002), Mumbai (2003), Ayodhya (2005), Varanasi (2006), Hyderabad (2007) and many others. -

Global Digital Cultures: Perspectives from South Asia

Revised Pages Global Digital Cultures Revised Pages Revised Pages Global Digital Cultures Perspectives from South Asia ASWIN PUNATHAMBEKAR AND SRIRAM MOHAN, EDITORS UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS • ANN ARBOR Revised Pages Copyright © 2019 by Aswin Punathambekar and Sriram Mohan All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America Printed on acid- free paper First published June 2019 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication data has been applied for. ISBN: 978- 0- 472- 13140- 2 (Hardcover : alk paper) ISBN: 978- 0- 472- 12531- 9 (ebook) Revised Pages Acknowledgments The idea for this book emerged from conversations that took place among some of the authors at a conference on “Digital South Asia” at the Univer- sity of Michigan’s Center for South Asian Studies. At the conference, there was a collective recognition of the unfolding impact of digitalization on various aspects of social, cultural, and political life in South Asia. We had a keen sense of how much things had changed in the South Asian mediascape since the introduction of cable and satellite television in the late 1980s and early 1990s. We were also aware of the growing interest in media studies within South Asian studies, and hoped that the conference would resonate with scholars from various disciplines across the humanities and social sci- ences. -

ALL INDIA INSTITUTE of MEDICAL SCIENCES Ansari Nagar, New Delhi - 110608

ALL INDIA INSTITUTE OF MEDICAL SCIENCES Ansari Nagar, New Delhi - 110608 ALL INDIA ENTRANCE EXAMINATION FOR ADMISSION TO MD/MS/DIPLOMA AND MDS COURSES - 2011 RESULT NOTIFICATION NO. 14/2011 The following is the list of candidates who have qualified for MD/MS/Diploma and MDS courses for admission to various Medical/Dental Colleges/Institutions in India against 50% seats quota on the basis of All India Entrance Examination held on Sunday, the 9th January, 2011. In pursuance to Directorate General of Health Services (Medical Examination Cell) Letter No. U-12021/29/2010-MEC dated 11th Feb., 2011, the list is category and roll number wise and the respective category rank is given in parenthesis against each roll number. The admission is subject to verification of eligibility criteria & original documents as given in the Prospectus. The Institute is not responsible for any printing error. The allocation of subject and Medical College will be done by the Directorate General of Health Services as per revised counselling schedule available on website of Ministry of Health & Family Welfare namely www.mohfw.nic.in. Individual intimation in this respect is being sent separately. Result is displayed on the notice board of Examination Section, AIIMS, New Delhi and is also available on web sites www.aiims.ac.in, www.aiims.edu and www.aiimsexams.org which include category and over all rank of the candidates. MD/MS/DIPLOMA COURSES Roll No. Name Category Over all Rank Category Rank 1100002 Harsh Jayantkumar Shah UR 1643 1619 1100006 Senthilnathan M UR