Don't Mention the War! I Mentioned It Once, but I Think I Got Away with It All Right

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

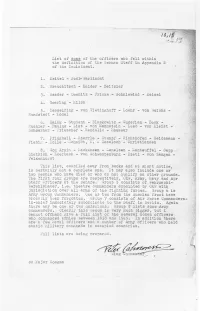

List of Some of the Officers ~~10 Fall Within the Definition of the German

-------;-:-~---,-..;-..............- ........- List of s ome of t he officers ~~10 fall within t he de finition of t he German St af f . in Appendix B· of t he I n cii c tment . 1 . Kei t e l - J odl- Aar l imont 2 . Br auchi t s ch - Halder - Zei t zl er 3. riaeder - Doeni t z - Fr i cke - Schni ewi nd - Mei s el 4. Goer i ng - fu i l ch 5. Kes s el r i ng ~ von Vi et i nghof f - Loehr - von ~e i c h s rtun c1 s t ec t ,.. l.io d eL 6. Bal ck - St ude nt - Bl a skowi t z - Gud er i an - Bock Kuchl er - Pa ul us - Li s t - von Manns t ei n - Leeb - von Kl e i ~ t Schoer ner - Fr i es sner - Rendul i c - Haus s er 7. Pf l ug bei l - Sper r l e - St umpf - Ri cht hof en - Sei a emann Fi ebi £; - Eol l e - f)chmi dt , E .- Des s l och - .Christiansen 8 . Von Arni m - Le ck e ris en - :"emelsen - l.~ a n t e u f f e l - Se pp . J i et i i ch - 1 ber ba ch - von Schweppenburg - Di e t l - von Zang en t'al kenhol's t rr hi s' list , c ompiled a way f r om books and a t. shor t notice, is c ertai nly not a complete one . It may also include one or t .wo neop .le who have ai ed or who do not q ual ify on other gr ounds . -

Assessing the Implications of Possible Changes to Women in Service Restrictions: Practices of Foreign Militaries and Other Organizations

Assessing the Implications of Possible Changes to Women in Service Restrictions: Practices of Foreign Militaries and Other Organizations Annemarie Randazzo-Matsel • Jennifer Schulte • Jennifer Yopp DIM-2012-U-000689-Final July 2012 Photo credit line: Young Israeli women undergo tough, initial pre-army training at Zikim Army Base in southern Israel. REUTERS/Nir Elias Approved for distribution: July 2012 Anita Hattiangadi Research Team Leader Marine Corps Manpower Team Resource Analysis Division This document represents the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the Department of the Navy. Cleared for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited. Specific authority: N00014-11-D-0323. Copies of this document can be obtained through the CNA Document Control and Distribution Section at 703-824-2123. Copyright 2012 CNA This work was created in the performance of Federal Government Contract Number N00014-11-D-0323. Any copyright in this work is subject to the Government's Unlimited Rights license as defined in DFARS 252.227-7013 and/or DFARS 252.227-7014. The reproduction of this work for commercial purposes is strictly prohibited. Nongovernmental users may copy and distribute this document in any medium, either commercially or noncommercially, provided that this copyright notice is reproduced in all copies. Nongovernmental users may not use technical measures to obstruct or control the read-ing or further copying of the copies they make or distribute. Nongovernmental users may not accept compensation of any manner in exchange for copies. All other rights reserved. Contents Executive summary . 1 Foreign militaries . 3 Australia . 4 ADF composition . -

Dans För Mogen Ungdom Än Ohly

Nr 24 i webbform 061013 Dans för mogen ungdom Förr i tiden kunde man läsa annonser i DN om dansstället Lorry i Sundbyberg där det varje helg var dans för "mogen ungdom och frånskilda". Det är nog något sådant som har föresvävat arrangörerna i Flygelkören när de lördagen den 21 oktober ordnar dans i Vita Huset på Djingis Khan, från 21.30. Carabanda står för medryckande Balkanmusik medan Sten Gustens lovar åstadkomma mogen blandad Svängmusik. Det verkar lovande. Än Ohly då? Förra veckan nämnde jag de kritiska inläggen i Flamman mot tre ledande vänsterpartisters inlägg i Upsala Nya Tidning strax efter valet, där de krävde att Sverige skulle öppna ett konsulat den kurdiska delen av Irak, framför allt med hänsyn till de många därifrån som nu bor eller vistas i Sverige men besöker sitt gamla hemland och kan behöva assistans. Det kravet kritiserades starkt av ett antal vänsterpartister i Malmö och Lund som menade att det innebar ett erkännande av ockupationen. I veckans nummer svarar äntligen Ulla Hoffmann och Jacob Johnson, avgången respektive ny riksdagsledamot. De säger att representationen skulle öppnas i en del av Irak där (den kurdiska) regeringen har kontroll över territoriet och ett relativt lugn råder, vilket tillhör de gängse reglerna för diplomatisk representation, och att kravet verkligen inte innebär något erkännande av ockupationen. Men vänta! Var det inte tre undertecknare i UNT? Jovisst, Lars Ohly var med. Den här gången saknas han, utan att någon förklaring ges. Vi väntar med spänning på en. Ett slag för miljön Inte bara oppositionspartierna utan även miljöorganisationer har kritiserat regeringsförklaringen och vissa redan fattade beslut som dåliga för miljö. -

Nigeria: the Challenge of Military Reform

Nigeria: The Challenge of Military Reform Africa Report N°237 | 6 June 2016 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. The Long Decline .............................................................................................................. 3 A. The Legacy of Military Rule ....................................................................................... 3 B. The Military under Democracy: Failed Promises of Reform .................................... 4 1. The Obasanjo years .............................................................................................. 4 2. The Yar’Adua and Jonathan years ....................................................................... 7 3. The military’s self-driven attempts at reform ...................................................... 8 III. Dimensions of Distress ..................................................................................................... 9 A. The Problems of Leadership and Civilian Oversight ................................................ -

Conrad Von Hötzendorf and the “Smoking Gun”: a Biographical Examination of Responsibility and Traditions of Violence Against Civilians in the Habsburg Army 55

1914: Austria-Hungary, the Origins, and the First Year of World War I Günter Bischof, Ferdinand Karlhofer (Eds.) Samuel R. Williamson, Jr. (Guest Editor) CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | VOLUME 23 uno press innsbruck university press Copyright © 2014 by University of New Orleans Press, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to UNO Press, University of New Orleans, LA 138, 2000 Lakeshore Drive. New Orleans, LA, 70119, USA. www.unopress.org. Printed in the United States of America Design by Allison Reu Cover photo: “In enemy position on the Piave levy” (Italy), June 18, 1918 WK1/ALB079/23142, Photo Kriegsvermessung 5, K.u.k. Kriegspressequartier, Lichtbildstelle Vienna Cover photo used with permission from the Austrian National Library – Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Vienna Published in the United States by Published and distributed in Europe University of New Orleans Press by Innsbruck University Press ISBN: 9781608010264 ISBN: 9783902936356 uno press Contemporary Austrian Studies Sponsored by the University of New Orleans and Universität Innsbruck Editors Günter Bischof, CenterAustria, University of New Orleans Ferdinand Karlhofer, Universität Innsbruck Assistant Editor Markus Habermann -

Karin Erika MARKIDES Ulrica MESSING

European Commission Karin Erika MARKIDES Deputy Director General, Vinnova, Sweden Karin Markides was awarded a Master of Science Degree from the University of Stockholm in 1974 and a Ph.D. from the same University in 1984. In 1986, Karin was appointed Docent in Analytical Chemistry at the University of Stockholm. Between June 1984 and August 1990, Karin held different academic positions at the Chemistry Department of Brigham Young University, USA. Since 1989, she holds a Chair and Professorship in Analytical Chemistry at the Chemistry Department of the University of Uppsala, Sweden. She is also a Visiting Professor at Stanford University, Chemistry Department, USA. Since April 2004, he holds the position of Vice Director General at VINNOVA (Swedish Agency for Innovation Systems). She is also holds the Chair, is a board member and member of several scientific and academic societies. Karin Markides the author of more than 200 scientific publications and owns 6 scientific patents. Ulrica MESSING Minister of Communications and Regional Policy of Sweden Ulrica Messing was born in Hällefors, Sweden, on January 31, 1968. In high school she attended the social studies programme. She started her political career in 1987 when she became ombudsman at Sandviken and Gävleborgs branches of the Swedish Social Democratic Youth League. In 1990 she continued her social work for “Hassela Solidaritet and Hassela Kollektivet”, a substance abuse treatment centre. In the same year she became alternate member of the Swedish Social Democratic Youth League. In 1991 she became a member of the Swedish Riksdag and one year later, member of the National Board of Institutional Care and the National Board for Youth Affairs. -

India's National Security Annual Review 2010

Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:22 24 May 2016 India’s National Security Annual Review 2010 Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:22 24 May 2016 216x138 HB + 8colour pages ii Ç India’s National Security This series, India’s National Security: Annual Review, was con- ceptualised in the year 2000 in the wake of India’s nuclear tests and the Kargil War in order to provide an in-depth and holistic assessment of national security threats and challenges and to enhance the level of national security consciousness in the country. The first volume was published in 2001. Since then, nine volumes have been published consecutively. The series has been supported by the National Security Council Secretariat and the Confederation of Indian Industry. Its main features include a review of the national security situation, an analysis of upcoming threats and challenges by some of the best minds in India, a periodic National Security Index of fifty top countries of the world, and a chronology of major events. It now serves as an indispensable source of information and analysis on critical national security issues of India. Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:22 24 May 2016 India’s National Security Annual Review 2010 Editor-in-Chief SATISH KUMAR Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:22 24 May 2016 LONDON NEW YORK NEW DELHI Under the auspices of Foundation for National Security Research, New Delhi First published 2011 in India by Routledge 912 Tolstoy House, 15–17 Tolstoy Marg, Connaught Place, New Delhi 110 001 Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Transferred to Digital Printing 2011 © 2010 Satish Kumar Typeset by Star Compugraphics Private Ltd D–156, Second Floor Sector 7, NOIDA 201 301 All rights reserved. -

Omställningsstöd För Riksdagsledamöter

2012/13 mnr: K7 pnr: V51 Motion till riksdagen 2012/13:K7 av Mia Sydow Mölleby m.fl. (V) med anledning av framst. 2012/13:RS7 Omställningsstöd för riksdagsledamöter Förslag till riksdagsbeslut 1. Riksdagen beslutar om ändring i lagen om ekonomiska villkor för riks- dagens ledamöter 13a kap. 1 § sista meningen enligt vad som anförs i motionen. 2. Riksdagen beslutar om ändring i lagen om ekonomiska villkor för riks- dagens ledamöter 13 kap. 1 § sista meningen enligt vad som anförs i mot- ionen. 3. Riksdagen beslutar att 13a kap. 12 § i lagen om ekonomiska villkor för riksdagens ledamöter tillförs en ny punkt enligt vad som anförs i motion- en. Reglerna ska gälla alla som väljs in 2014 Förslagen i propositionen grundar sig på Villkorskommitténs utredning 2012/13:URF1 Omställningsstöd för riksdagsledamöter. I direktiven till denna utredning angavs att de nya bestämmelserna inte ska gälla för de leda- möter som invaldes till riksdagen före 2014. Vänsterpartiet anser att det enda rimliga är att samma regler och villkor gäller för alla som inväljs och vi avslår förslaget att de ledamöter som redan suttit en eller flera mandatperioder ska få förmånligare regler än de som kommer som nyvalda. Vi föreslår att riksdagen beslutar att det nya kapitlet 13a 1 § sista mening- en i lagen om ekonomiska villkor för riksdagens ledamöter ges följande ly- delse: ”Bestämmelserna i detta kapitel gäller för ledamöter som väljs in i riksdagen genom valet 2014 eller som inträder senare i riksdagen.” Detta bör riksdagen besluta. 1 Fel! Okänt namn på dokumentegenskap. :Fel! Okänt namn på Ledamöter som tidigare lämnat riksdagen dokumentegenskap. -

Hybrid Threats in the 21St Century

Band 17 / 2016 Band 17 / 2016 Die Vernetzung von Gesellschaften wird durch technische Errungenschaften immer komplexer. Somit erweitern Century sich auch Einflussfaktoren auf die Sicherheit von Gesell- st schaftssystemen. Networked Insecurity – Spricht man in diesem Zusammenhang in sicherheits- politischen Fachkreisen von hybrider Kampfführung, ge- hen die Autoren in diesem Buch einen Schritt weiter und Hybrid Threats beschäftigen sich mit Optionen der Machtprojektion, die st über Kampfhandlungen hinausgehen. Dabei sehen sie in the 21 Century hybride Bedrohungen als sicherheitspolitische Herausfor- derung der Zukunft. Beispiele dazu untermauern den im Buch vorangestellten theoretischen Teil. Mögliche Hand- lungsoptionen runden diese Publikation ab. Networked Insecurity – Hybrid Threats in the 21 Threats – Hybrid Insecurity Networked ISBN: 978-3-903121-01-0 Anton Dengg and Michael Schurian (Eds.) 17/16 Schriftenreihe der Dengg, Schurian (Eds.) Dengg, Landesverteidigungsakademie Schriftenreihe der Landesverteidigungsakademie Anton Dengg, Michael Schurian (Eds.) Networked Insecurity – Hybrid Threats in the 21st Century 17/2016 Vienna, June 2016 Imprint: Copyright, Production, Publisher: Republic of Austria / Federal Ministry of Defence and Sports Rossauer Lände 1 1090 Vienna, Austria Edited by: National Defence Academy Institute for Peace Support and Conflict Management Stiftgasse 2a 1070 Vienna, Austria Schriftenreihe der Landesverteidigungsakademie Copyright © Republic of Austria / Federal Ministry of Defence and Sports All rights reserved -

Megafoner Och Cocktailpartyn

Megafoner och cocktailpartyn – en granskning av riksdagsledamöters bloggar GÖTEBORGS UNIVERSITET JMG, Institutionen för journalistik, medier och kommunikation Boris Vasic Examensarbete i journalistik 22,5 hp, VT/2010 Handledare: Anna Jaktén Megafoner och cocktailpartyn Sociala medier handlar om interaktivitet och tvåvägskommunikation. Både experter och riksdagspartierna själva håller med om att detta är ett gyllene tillfälle för politiker att ta direktkontakt med väljarna. Men min undersökning visar att majoriteten av riksdagsledamöternas bloggar är ingenting annat än digitala megafoner. En knapp femtedel följer partiernas riktlinjer för sociala medier. De skriver utifrån sitt personliga engagemang för politiken och uppmuntrar reaktioner från läsarna. Det finns dock ljuspunkter: Fredrick Federley (c) finns på många kanaler ute på nätet och använder dem på sätt som partierna beskriver som ideala. – Ska man förstå sociala medier måste man se det som ett cocktailparty – man kan inte stå i ett hörn och gapa ut saker, säger han. 1 Förteckning över presentationen Varför sociala medier? Syftet med artikeln är att svara på frågan i rubriken: varför satsar partierna på sociala medier? Svaren kommer från intervjuer med riksdagspartiernas ansvariga för sociala medier. Artikeln ska belysa premisserna och förväntningarna som riksdagsledamöterna har när de jobbar med sociala medier. Den nya valstugan blev en megafon Detta är själva undersökningen: 140 bloggar, men en knapp femtedel följer riktlinjerna som partierna satt upp. Här visar jag upp exempel från några av bloggarna, samt kommentarer på undersökningens resultat från partiernas ansvariga. En djupare förklaring ges även av Henrik Oscarsson, professor i statsvetenskap vid Göteborgs Universitet. En bloggares bekännelser Fredrick Federley (c) är artikelseriens case. Som bloggande riksdagsledamot ger han en djupare bild av funderingar kring politik och sociala medier. -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Party Organisation and Party Adaptation: Western European Communist and Successor Parties Daniel James Keith UNIVERSITY OF SUSSEX Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, April, 2010 ii I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature :……………………………………… iii Acknowledgements My colleagues at the Sussex European Institute (SEI) and the Department of Politics and Contemporary European Studies have contributed a wealth of ideas that contributed to this study of Communist parties in Western Europe. Their support, generosity, assistance and wealth of knowledge about political parties made the SEI a fantastic place to conduct my doctoral research. I would like to thank all those at SEI who have given me so many opportunities and who helped to make this research possible including: Paul Webb, Paul Taggart, Aleks Szczerbiak, Francis McGowan, James Hampshire, Lucia Quaglia, Pontus Odmalm and Sally Marthaler. -

Varken Hurra Eller Bua” En Studie Av VPK:S Hållning Gentemot De Kommunistiska Öststatsregimerna 1977-1990 Speglat Genom Dess Partitidning Arbetartidningen Ny Dag

Växjö Universitet Institutionen för Humaniora 070613 Historia Handledare: Per-Olof Andersson Examinator: Malin Lennartson HIC160 ”Varken hurra eller bua” En studie av VPK:s hållning gentemot de kommunistiska Öststatsregimerna 1977-1990 speglat genom dess partitidning Arbetartidningen Ny Dag Christian Tegnvallius Innehållsförteckning INLEDNING ..........................................................................................................4 SYFTE ..................................................................................................................5 METOD OCH AVGRÄNSNING ............................................................................5 KÄLLMATERIAL..................................................................................................7 TEORI...................................................................................................................8 Det medieteoretiska fältet ............................................................................................................................ 8 Mass society theory....................................................................................................................................... 8 Pressens roll .................................................................................................................................................. 9 Demokrati.................................................................................................................................................... 10 TIDIGARE FORSKNING