Russian Expansion Or Exodus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Voronezh Tyre Plant Company Profile Company Name (Short): Vshz CJSC CEO: Valeriy Y

Dear readers, The industrial policy pursued by the regional government is in close alignment with the Devel- opment Strategy of Voronezh region up to 2020. It has been approved after thorough consideration and negotiations with non-governmental organi- zations and professional experts. Thus, the region is in for radical system changes in the regional economy. The regional government is successfully develop- ing innovative system. The main directions of clus- ter development policy have been outlined, which increases the region’s competitive advantages and enhances connections between branches and in- dustries. The regional government has managed to create congenial investment climate in the region. The government is coming up with new ways of supporting Rus- sian and foreign investors, developing the system of subsidies and preferences. Innovative industrial parks and zones are set up. Their infrastructure is financed from the state and regional budgets. Voronezh region is one of top 10 in the investment attractiveness rating and is carrying out over 30 investment projects. All the projects are connected with technical re-equipment of companies and creation of high-technology manufac- turers. The number of Russian and foreign investors is constantly increasing. In the Catalogue of Industrial Companies of Voronezh Region, you will find in- formation on the development of industries in Voronezh region, structural and quality changes in the industrial system. Having read this catalogue, you will learn about the industrial potential of Vo- ronezh region, the companies’ production facilities, history and product range. The regional strategy is based on coordinated efforts, a constructive dialogue between private businesses, the government and non-governmental organiza- tions. -

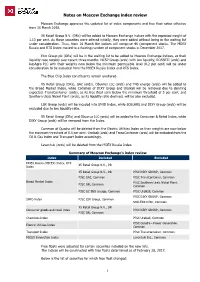

Notes on Moscow Exchange Index Review

Notes on Moscow Exchange index review Moscow Exchange approves the updated list of index components and free float ratios effective from 16 March 2018. X5 Retail Group N.V. (DRs) will be added to Moscow Exchange indices with the expected weight of 1.13 per cent. As these securities were offered initially, they were added without being in the waiting list under consideration. Thus, from 16 March the indices will comprise 46 (component stocks. The MOEX Russia and RTS Index moved to a floating number of component stocks in December 2017. En+ Group plc (DRs) will be in the waiting list to be added to Moscow Exchange indices, as their liquidity rose notably over recent three months. NCSP Group (ords) with low liquidity, ROSSETI (ords) and RosAgro PLC with their weights now below the minimum permissible level (0.2 per cent) will be under consideration to be excluded from the MOEX Russia Index and RTS Index. The Blue Chip Index constituents remain unaltered. X5 Retail Group (DRs), GAZ (ords), Obuvrus LLC (ords) and TNS energo (ords) will be added to the Broad Market Index, while Common of DIXY Group and Uralkali will be removed due to delisting expected. TransContainer (ords), as its free float sank below the minimum threshold of 5 per cent, and Southern Urals Nickel Plant (ords), as its liquidity ratio declined, will be also excluded. LSR Group (ords) will be incuded into SMID Index, while SOLLERS and DIXY Group (ords) will be excluded due to low liquidity ratio. X5 Retail Group (DRs) and Obuvrus LLC (ords) will be added to the Consumer & Retail Index, while DIXY Group (ords) will be removed from the Index. -

An Overview of Boards of Directors at Russia's Largest Public Companies

An Overview Of Boards Of Directors At Russia’s Largest Public Companies Andrei Rakitin Milena Barsukova Arina Mazunova Translated from Russian August 2020 Key Results According to information disclosed by 109 of Russia’s largest public companies: “Classic” board compositions of 11, nine, and seven seats prevail The total number of persons on Boards of the companies under study is not as low as it might seem: 89% of all Directors were elected to only one such Board Female Directors account for 12% and are more often elected to the audit, nomination, and remuneration committees than to the strategy committee Among Directors, there are more “humanitarians” than “techies,” while the share of “techies” among chairs is greater than across the whole sample The average age for Directors is 53, 56 for Chairmen, and 58 for Independent Directors Generation X is the most visible on Boards, and Generation Y Directors will likely quickly increase their presence if the impetuous development of digital technologies continues The share of Independent Directors barely reaches 30%, and there is an obvious lack of independence on key committees such as audit Senior Independent Directors were elected at 17% of the companies, while 89% of Chairs are not independent The average total remuneration paid to the Board of Directors is RUR 69 million, with the difference between the maximum and minimum being 18 times Twenty-four percent of the companies disclosed information on individual payments made to their Directors. According to this, the average total remuneration is approximately RUR 9 million per annum for a Director, RUR 17 million for a Chair, and RUR 11 million for an Independent Director The comparison of 2020 findings with results of a similar study published in 2012 paints an interesting dynamic picture. -

Strategy Development for Sustainable Use of Groundwater and Aggregates in Vyborg District, Leningrad Oblast

Activity 4, Report 2: Strategy for sustainable management of ground water and aggregate extraction areas for Vyborg district The European Union´s Tacis Cross-Border Co-operation Small Project Facility Programme Strategy development for sustainable use of groundwater and aggregates in Vyborg district, Leningrad Oblast Activity 4, Report 2: Strategy for sustainable management of ground water and aggregate extraction areas in Vyborg District Activity 4, Report 2: Strategy for sustainable management of ground water and aggregate extraction areas for Vyborg district Strategy development for sustainable use of ground water and aggregates in Vyborg District, Leningrad Oblast, Russia Activity 4, Report 2: Strategy for sustainable management of ground water and aggregate extraction areas in Vyborg District Edited by Leveinen J. and Kaija J. Contributors Savanin V., Philippov N., Myradymov G., Litvinenko V., Bogatyrev I., Savenkova G., Dimitriev D., Leveinen J., Ahonen I, Backman B., Breilin O., Eskelinen A., Hatakka, T., Härmä P, Jarva J., Paalijärvi M., Sallasmaa, O., Sapon S., Salminen S., Räisänen M., Activity 4, Report 2: Strategy for sustainable management of ground water and aggregate extraction areas for Vyborg district Contents Contents ...............................................................................................................................................3 Summary ..............................................................................................................................................4 Introduction..........................................................................................................................................5 -

PRESS RELEASE JSC ALROSA Announces Purchase of a 25

PRESS RELEASE JSC ALROSA Announces Purchase of a 25 Percent Interest in OJSC Polyus Gold August, 2007, Moscow. Joint-Stock Company ALROSA signed an agreement with ONEXIM Group to buy a 25 percent stake in the Open Joint-Stock Company Polyus Gold (RTS, MICEX, and LSE – PLZL), Russia’s largest gold producer. “This deal was implemented as part of the development strategy approved by the Supervisory Board of JSC ALROSA. Among other things, ALROSA focuses on diversifying into other sectors. The purchase of a significant stake in Polyus Gold, which pursues an effective production strategy, will enable ALROSA to access a market with considerable long-term prospects and will further boost the development and economic growth of regions in Central and Eastern Siberia,” said President of ALROSA Sergei Vybornov. Open Joint-Stock Company Polyus Gold (RTS, MICEX, and LSE – PLZL) – is the leading gold producer in Russia and one of the biggest players in gold mining in the world in terms of deposits and production. The asset portfolio of Polyus Gold includes ore and alluvial gold deposits in the Krasnoyarsk Territory, the Irkutsk, Magadan, and Amur regions, and in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia), where the company operates gold exploration and mining projects. As of January 1, 2007, the mineral resource base of OJSC Polyus Gold comprises 3,000.7 tons of gold in B+C1+C2 reserves, including 2,149 tons of B+C1 reserves. Joint-Stock Company ALROSA – is a global leader in diamond exploration, mining and sales of rough diamonds, and in cut diamond manufacture. ALROSA accounts for 97 percent of Russia’s rough diamond production and for 25 percent of the global output of rough diamonds. -

Forest Economy in the U.S.S.R

STUDIA FORESTALIA SUECICA NR 39 1966 Forest Economy in the U.S.S.R. An Analysis of Soviet Competitive Potentialities Skogsekonomi i Sovjet~rnionen rned en unalys av landets potentiella konkurrenskraft by KARL VIICTOR ALGTTERE SICOGSH~GSICOLAN ROYAL COLLEGE OF FORESTRY STOCKHOLM Lord Keynes on the role of the economist: "He must study the present in the light of the past for the purpose of the future." Printed in Sweden by ESSELTE AB STOCKHOLM Foreword Forest Economy in the U.S.S.R. is a special study of the forestry sector of the Soviet economy. As such it makes a further contribution to the studies undertaken in recent years to elucidate the means and ends in Soviet planning; also it attempts to assess the competitive potentialities of the U.S.S.R. in international trade. Soviet studies now command a very great interest and are being undertaken at some twenty universities and research institutes mainly in the United States, the United Kingdoin and the German Federal Republic. However, it would seem that the study of the development of the forestry sector has riot received the detailed attention given to other fields. In any case, there have not been any analytical studies published to date elucidating fully the connection between forestry and the forest industries and the integration of both in the economy as a whole. Studies of specific sections have appeared from time to time, but I have no knowledge of any previous study which gives a complete picture of the Soviet forest economy and which could faci- litate the marketing policies of the western world, being undertaken at any university or college. -

Cross-Border Cooperation ENPI 2007-2013 in EN

TUNNUS Tunnuksesta on useampi väriversio eri käyttötarkoituksiin. Väriversioiden käyttö: Pääsääntöisesti logosta käytetään neliväriversiota. CMYK - neliväripainatukset kuten esitteet ja värillinen sanomalehtipainatus. PMS - silkkipainatukset ym. erikoispainatukset CMYK PMS Cross-border C90% M50% Y5% K15% PMS 287 C50% M15% Y5% K0% PMS 292 C0% M25% 100% K0% PMS 123 cooperation K100% 100% musta Tunnuksesta on käytössä myös mustavalko- , 1-väri ja negatiiviversiot. Mustavalkoista tunnusta käytetään mm. mustavalkoisissa lehti-ilmoituspohjissa. 1-väri ja negatiiviversioita käytetään vain erikoispainatuksissa. Mustavalkoinen 1-väri K80% K100% K50% K20% K100% Nega Painoväri valkoinen The programme has been involved in several events dealing with cross-border cooperation, economic development in the border area and increasing cooperation in various fi elds. Dozens of events are annually organised around Europe on European Cooperation Day, 21 September. The goal of the campaign is to showcase cooperation and project activities between the European Union and its partner countries. The project activities result in specialist networks, innovations, learning experiences and the joy of doing things together. Contents Editorial, Petri Haapalainen 4 Editorial, Rafael Abramyan 5 Programme in fi gures 6-7 BUSINESS AND ECONOMY 8 BLESK 9 Innovation and Business Cooperation 9 RESEARCH AND EDUCATION 10 Arctic Materials Technologies Development 11 Cross-border Networks and Resources for Common Challenges in Education – EdNet 11 TECHNOLOGY AND INNOVATIONS 12 Open Innovation Service for Emerging Business – OpenINNO 13 International System Development of Advanced Technologies Implementation in Border Regions – DATIS 13 SERVICES AND WELL-BEING 14 IMU - Integrated Multilingual E-Services for Business Communication 15 Entrepreneurship Development in Gatchina District - GATE 15 TOURISM 16 Castle to Castle 17 St. -

Transparency and Disclosure by Russian State-Owned Enterprises

Transparency And Disclosure By Russian State-Owned Enterprises Standard & Poor’s Governance Services Prepared for the Roundtable on Corporate Governance organized by the OECD in Moscow on June 3, 2005 Julia Kochetygova Nick Popivshchy Oleg Shvyrkov Vladimir Todres Christine Liadskaya June 2005 Transparency & Disclosure by Russian State-Owned Enterprises Transparency and Disclosure by Russian State-Owned Enterprises Executive Summary This survey of transparency and disclosure (T&D) by Russian state-owned companies by Standard & Poor’s Governance Services was prepared at the request of the OECD Roundtable on Corporate Governance. According to the OECD Guidelines on Corporate Governance of SOEs, “the state should act as an informed and active owner and establish a clear and consistent ownership policy, ensuring that the governance of state-owned enterprises is carried out in a transparent and accountable manner” (Chapter III). Further, “large or listed SOEs should disclose financial and non financial information according to international best practices” (Chapter V). In stark contrast with these principles, the study revealed consistent differences in disclosure standards between the state-controlled and similarly sized public Russian companies. This is in line with the notion that transparency of state-controlled enterprises is hampered by the tendency of the Russian government and individual officials to use their influence on such companies to promote political or individual goals that often diverge from commercial motives and investor interests. High standards of transparency and disclosure, on the other hand, are a cornerstone in the foundation of good governance. They provide legitimate stakeholders--whether creditors, minority shareholders, taxpayers, or the general public--with the information they need to be able to begin to hold government decision-makers accountable for their actions. -

Yakutia) “…The Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) Is the Largest Region in the Russian Federation and One of the Richest in Natural Resources

Investor's Guide to the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) “…The Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) is the largest region in the Russian Federation and one of the richest in natural resources. Needless to say, the stable and dynamic development of Yakutia is of key importance to both the Far Eastern Federal District and all of Russia…” President of the Russian Federation Vladimir Putin “One of the fundamental priorities of the Government of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) is to develop comfortable conditions for business and investment activities to ensure dynamic economic growth” Head of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) Egor Borisov 2 Contents Welcome from Egor Borisov, Head of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) 5 Overview of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) 6 Interesting facts about the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) 7 Strategic priorities of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) investment policy 8 Seven reasons to start a business in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) 10 1. Rich reserves of natural resources 10 2. Significant business development potential for the extraction and processing of mineral and fossil resources 12 3. Unique geographical location 15 4. Stable credit rating 16 5. Convenient conditions for investment activity 18 6. Developed infrastructure for the support of small and medium-sized enterprises 19 7. High level of social and economic development 20 Investment infrastructure 22 Interaction with large businesses 24 Interaction with small and medium-sized enterprises 25 Other organisations and institutions 26 Practical information on doing business in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) 27 Public-Private Partnership 29 Information for small and medium-sized enterprises 31 Appendix 1. -

Press Release Sales of New Commercial Vehicles in Russia* in the First Half of 2012 Association of European Businesses

ASSOCIATION АССОЦИАЦИЯ OF EUROPEAN BUSINESSES ЕВРОПЕЙСКОГО БИЗНЕСА РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ, RUSSIAN FEDERATION 127473 Москва ул. Краснопролетарская, д. 16 стр. 3 Ulitsa Krasnoproletarskaya 16, bld. 3, Moscow, 127473 Тел. +7 495 234 2764 Факс +7 495 234 2807 Tel +7 495 234 2764 Fax +7 495 234 2807 [email protected] http://www.aebrus.ru [email protected] http://www.aebrus.ru Moscow, 13 July 2012 PRESS RELEASE SALES OF NEW COMMERCIAL VEHICLES IN RUSSIA* IN THE FIRST HALF OF 2012 Reference data are sales of commercial vehicles to end users and body manufacturers. All these vehicles have been unregistered before, e.g. new vehicles. Vehicles are clustered in four different segments: light commercial vehicles (LCV) from 2,8 to 6 tons gross vehicle weight (GVW); medium duty trucks (MDT) from 6 to 16 tons GVW; heavy duty trucks (HDT) above 16 tons GVW; and buses. The figures reported below (with some exceptions in the LCV segment) relate only to the brands represented by the CVC. Andrey Chursin, Chairman of the Commercial Vehicles Committee, commented: " In the 2nd quarter of 2012, the commercial vehicles sector developed in line with our forecast for modest growth. The situation on the market in the second half of the year will almost entirely depend on the new law on the disposal of vehicles. At the moment, the details regarding the upcoming law and its implementation are still unclear – with less than a month left before this law comes into effect, information regarding the exact terms and conditions is yet to be made available. We would like to know the ‘rules of the game’ in advance, so that each market participant has time to prepare accordingly ". -

Adressverzeichnis

ADRESSVERZEICHNIS ANHÄNGER & AUFBAUTEN . .Seite 11–13 BUSSE. .Seite 13–16 LKW und TRANSPORTER . .Seite 16–19 SPEZIALFAHRZEUGE . .Seite 19–22 ANHÄNGER & Aebi Schmidt ALF Fahrzeugbau Andreoli Rimorchi S.r.l. Deutschland GmbH GmbH & Co.KG Via dell‘industria 17 AUFBAUTEN Albtalstraße 36 Gewerbehof 12 37060, Buttapietra (Verona) 79837 St. Blasien 59368 Werne ITALIEN Acerbi Veicoli Industriali S.p.A. Tel. +49.7672-412-0 Tel. +49.2389 98 48-0 Tel. +39 045 666 02 44 Strada per Pontecurone, 7 www.aebi-schmidt.com www.alf-fahrzeugbau.de www.andreoli-ribaltabili.it 15053 Castelnuovo Scrivia (AL) ITALIEN Agados spol. s.r.o. ALHU Fahrzeugtechnik GmbH Andres www.acerbi.it Rumyslová 2081 Borstelweg 22 Hermann Andres AG 59401 Velké Mezirici 25436 Tornesch Industriering 42 Achleitner Fahrzeugbau TSCHECHIEN Tel. +49.4122 - 90 67 00 3250 Lyss Innsbrucker Straße 94 Tel. +420 566 653 311 www.alhu.de SCHWEIZ 6300 Wörgl www.agados.cz Tel. +41 32 387 31 61 Asch- ÖSTERREICH AL-KO www.andres-lyss.ch wege & Tönjes Aucar- Tel. +43 5332-7811-0 Agados Anhänger Handels Alois Kober GmbH Zur Schlagge 17 Trailer SL www.achleitner.com GmbH Ichenhauser Str. 14 Annaburger Nutzfahrzeuge 49681 Garrel Pintor Pau Roig 41 2-3 Schwedter Str. 20a 89359 Kötz GmbH Tel. +49.4474-8900-0 08330 Premià de mar, Barcelona Ackermann Aufbauten & 16287 Schöneberg Tel. +49.8221-97-449 Torgauer Straße 2 www.aschwege-toenjes.de SPANIEN Fahrzeugvertrieb GmbH Tel. +49.33335 42811 www.al-ko.de 06925 Annaburg Tel. +34 93 752 42 82 Am Wallersteig 4 www.agados.de Tel. +49.35385-709-0 ASM – Equipamentos www.aucartrailer.com 87700 Memmingen-Steinheim Altinordu Trailer www.annaburger.de de Transporte, S Tel. -

Driving Force

Driving force 2020 ANNUAL REPORT Annual Report 2020 GRI 102-1, 102-48 – 102-52, 102-54 Contents About the Annual Report The scope of this annual report includes the companies of GTLK Group, which comprises JSC GTLK and its subsidiaries and associates. Financial statements are published annually. The current report covers the period from January 1, 2020 through December 31, 2020. 1.1. GTLKГТЛК todayсегодня 2 Support of sports and healthy lifestyle 71 A report containing information about GTLK’s activities in the area of sustainable Highlights 4 Observance of Human Rights 71 development in 2019 was published in July 2020. Message from the Chairman of the Board 8 Occupational health and safety 72 This report was prepared using the applicable Message from the CEO 10 Sponsorships and philanthropy 74 Global Reporting Initiative standards (GRI Standards) COVID-19 impact on GTLK business 12 Improvement of transport energy efficiency 76 and the principles of the UN Global Compact. In light of this, the report provides more extensive Procurement activities 78 information on sustainable development and ESG 2. GTLK profile 14 aspects. A list of the used standards is provided GTLK is a driving force 15 5. Corporate governance 80 in the GRI Index on page 228. GTLK in numbers 17 Competence and accountability 81 The main reasons for restatements of information in the report are the development Investments in development of domestic GTLK corporate governance practices 82 and improvement of the corporate reporting transport engineering 20 General shareholders meetings 85 system, and clarification of the scope of indicators Board of directors 86 and historical data.