The Fish-Lady and the Little Girl: a Case History Told from the Points of View of the Characters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Beginnings of the Art Colonies of Cape Ann, 1875-1925 Lecture Finding Aid & Transcript

THE BEGINNINGS OF THE ART COLONIES OF CAPE ANN, 1875-1925 LECTURE FINDING AID & TRANSCRIPT Speaker: Mary Rhinelander McCarl Date: 5/28/2011 Runtime: 57:17 Camera Operator: Bob Quinn Identification: VL33; Video Lecture #33 Citation: McCarl, Mary Rhinelander. “The Beginnings of the Art Colonies of Cape Ann, 1875-1925.” CAM Video Lecture Series, 5/28/2011. VL33, Cape Ann Museum Library & Archives, Gloucester, MA. Copyright: Requests for permission to publish material from this collection should be addressed to the Librarian/Archivist. Language: English Finding Aid: Description: Karla Kaneb, 4/25/2020. Transcript: Heidi McGrath, 6/30/2020. Video Description Recorded in the gallery of the North Shore Arts Association in East Gloucester, this video captures a lecture by local historian and Cape Ann Museum volunteer Mary Rhinelander McCarl in which she speaks about the late 19th century art colonies that flourished on Cape Ann. Drawn by the picturesque, accessible, and relatively inexpensive setting, many artists began to gather in Gloucester during The Beginnings of the Art Colonies of Cape Ann, 1875-1923 – VL33 – page 2 this time from several metropolitan areas while locally born artists thrived as well. McCarl discusses the careers of a few who were instrumental in establishing the arts-focused tenor of neighborhoods such as Annisquam and Rocky Neck. Her list includes both men and women and is presented within the context of evolving social and political influences. Subject list George Wainwright Harvey William and Emmeline Atwood Martha Hale Rogers Harvey Mary Rhinelander McCarl John K. Thurston Magnolia Ellen Day Hale Annisquam Helen M. Knowlton Rocky Neck Augustus Buhler Red Cottage Walter Lofthouse Dean Gallery on the Moors Charles Allan Winter North Shore Arts Association Alice Beach Winter Gloucester Society of Artists William Morris Hunt Transcript Suzanne Gilbert 00:09 So, thank you everyone for coming this afternoon. -

1 THANK YOU M'am by LANGSTON HUGHES A. Answer Thes

CLASS 11 SUBJECT – ENGLISH Chapters 1, 2, 3, CHAPTER – 1 THANK YOU M'AM By LANGSTON HUGHES A. Answer these questions in 30 – 40 words. 1.What did the boy try to snatch? Answer : The boy tried to snatch the purse of Mrs Luella Bates Washington Jones to get money so that he can purchase blue suede shoes. 2.Why was he not successful in his attempt? Answer: He was not successful in his attempt because the strap of a purse broke with the single tug the boy gave it from behind. But the boy’s weight and the weight of the purse combined caused him to lose his balance. So, instead of running away as he had hoped, the boy fell on his back on the sidewalk, and his legs flew up. 3.What did the woman do in response? Answer: The large woman simply turned around and kicked him directly to his blue-jeaned sitter. Then she reached down, picked the boy up by his shirt front, and shook him until his teeth rattled 4.Why did the boy not run away when the woman finally let go of his neck? Answer: The boy did not run away when the woman finally let go of his neck because he realized his mistakes and he was sorry for the action he had done. Moreover, he was given second chance by the woman when she took him at her apartment rather than to the police. 5.Why was the boy trying to steal? Answer: The boy said that the reason behind his action of trying to steal the purse of the woman was because he wanted to buy a pair of blue suede shoes. -

O MAGIC LAKE Чайкаthe ENVIRONMENT of the SEAGULL the DACHA Дать Dat to Give

“Twilight Moon” by Isaak Levitan, 1898 O MAGIC LAKE чайкаTHE ENVIRONMENT OF THE SEAGULL THE DACHA дать dat to give DEFINITION датьA seasonal or year-round home in “Russian Dacha or Summer House” by Karl Ivanovich Russia. Ranging from shacks to cottages Kollman,1834 to villas, dachas have reflected changes in property ownership throughout Russian history. In 1894, the year Chekhov wrote The Seagull, dachas were more commonly owned by the “new rich” than ever before. The characters in The Seagull more likely represent the class of the intelligencia: artists, authors, and actors. FUN FACTS Dachas have strong connections with nature, bringing farming and gardening to city folk. A higher class Russian vacation home or estate was called a Usad’ba. Dachas were often associated with adultery and debauchery. 1 HISTORYистория & ARCHITECTURE история istoria history дать HISTORY The term “dacha” originally referred to “The Abolition of Serfdom in Russia” by the land given to civil servants and war Alphonse Mucha heroes by the tsar. In 1861, Tsar Alexander II abolished serfdom in Russia, and the middle class was able to purchase dwellings built on dachas. These people were called dachniki. Chekhov ridiculed dashniki. ARCHITECTURE Neoclassicism represented intelligence An example of 19th century and culture, so aristocrats of this time neoclassical architecture attempted to reflect this in their architecture. Features of neoclassical architecture include geometric forms, simplicity in structure, grand scales, dramatic use of Greek columns, Roman details, and French windows. Sorin’s estate includes French windows, and likely other elements of neoclassical style. Chekhov’s White Dacha in Melikhovo, 1893 МéлиховоMELIKHOVO Мéлихово Meleekhovo Chekhov’s estate WHITE Chekhov’s house was called “The White DACHA Dacha” and was on the Melikhovo estate. -

Soldiers of Misfortune

U.S. Violations of the Optional Protocol on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict SOLDIERS OF MISFORTUNE Abusive U.S. Military Recruitment and Failure to Protect Child Soldiers Jania Sandoval (right) speaks with U.S. Army recruiter Sfc. Luis Medina at Wright College in Chicago. (Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images) ABOUT THE ACLU ........................................................................................................ 1 INTRODUCTION AND EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.................................................... 2 RECOMMENDATIONS.................................................................................................. 5 I. TARGETING OF YOUTH UNDER 17 FOR MILITARY RECRUITMENT (Article 3(1)-(2)) ................................................................................................................ 8 a. Recruiters in High Schools Target Students Under 17 ........................................... 9 a. Joint Advertising Market Research & Studies (JAMRS) Database Targets Youth Under 17 for Recruitment ............................................................................................. 11 b. Junior Reserve Officer Training Corps (JROTC) Target Children as Young as 14 for Recruitment ............................................................................................................. 12 c. Middle School Cadet Corps (MSCC), or Pre-JROTC, Targets Children as Young as 11 ............................................................................................................................. -

Summer Camp Song Book

Summer Camp Song Book 05-209-03/2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Numbers 3 Short Neck Buzzards ..................................................................... 1 18 Wheels .............................................................................................. 2 A A Ram Sam Sam .................................................................................. 2 Ah Ta Ka Ta Nu Va .............................................................................. 3 Alive, Alert, Awake .............................................................................. 3 All You Et-A ........................................................................................... 3 Alligator is My Friend ......................................................................... 4 Aloutte ................................................................................................... 5 Aouettesky ........................................................................................... 5 Animal Fair ........................................................................................... 6 Annabelle ............................................................................................. 6 Ants Go Marching .............................................................................. 6 Around the World ............................................................................... 7 Auntie Monica ..................................................................................... 8 Austrian Went Yodeling ................................................................. -

Toronto Slavic Quarterly. № 43. Winter 2013

TRANSLATION Aleksandr Chekhov In Melikhovo Translated by Eugene Alper This translation came about as the result of a surprise. A few years ago I noticed in amazement that despite the all-pervasive interest in everything and anything related to Anton Chekhov, among the multiple translations of his stories and plays, among the many biographies, research papers, and monographs describing his life in minute details and spliting hairs over the provenance of his characters, amidst the lively and bubbly pond of chekhovedenie, there was a lacuna: a number of memoirs about Chekhov writen by people closest to him were not available in English. Since then I have translated a couple of them—About Chekhov by his personal physician Isaac Altshuller (in Chekhov the Immigrant: Translating a Cultural Icon, Michael C. Finke, Julie de Sherbinin, eds., Slavica, 2007) and Anton Chekhov: A Brother’s Memoir by his younger brother Mikhail, Palgrave Macmillan, 2009, as have other translators, the most recent being Peter Sekirin’s Memories of Chekhov (McFarland, 2011)—but there is still more to be done. The book by Chekhov’s sister Maria, for one, remains unavailable to the English reader. The following translation of a memoir by Chekhov’s older brother Alek- sandr is aiming to place another litle patch over the gap. Aleksandr Chekhov (1855-1913) was an accomplished writer in his own right; although never rising to Anton’s level of celebrity (very few could), his short stories, essays, and articles were published regularly during his lifetime. This memoir—one of several writen by Aleksandr following Anton’s death in 1904—was published in 1911. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K--Grade 6. 1997 Edition

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 406 672 CS 215 782 AUTHOR Sutton, Wendy K., Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K--Grade 6. 1997 Edition. NCTE Bibliography Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0080-5; ISSN-1051-4740 PUB DATE 97 NOTE 447p.; Foreword by Patricia MacLachlan. For the 1993 (Tenth) Edition, see ED 362 878. Also prepared by the Committee To Revise the Elementary School Booklist. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 West Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096; phone: 1-800-369-6283 (Stock No. 00805: $16.95 members, $22.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC18 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescent Literature; Annotated Bibliographies; *Childrens Literature; Elementary Education; Fiction; Nonfiction; Picture Books; Poetry; Preschool Education; Reading Interests; *Reading Material Selection; *Recreational Reading IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction ABSTRACT This book contains descriptions of over 1,200 books published between 1993 and 1995, all chosen for their high quality and their interest to children, parents, teachers, and librarians. Materials described in the book include fiction, nonfiction, poetry, picture books, young adult novels, and interactive CD-ROMs. Individual book reviews in the book include a description of the book's form and content, information on the type and medium of the illustrations, suggestions on how the book might best be incorporated into the elementary school curriculum, and full bibliographic information. A center insert in the book displays photographs of many of the titles, allowing readers to see the quality of the illustrations for themselves. -

The Isle Royale Folkefiskerisamfunn: Familier Som Levde Av Fiske

THE ISLE ROYALE FOLKEFISKERISAMFUNN: FAMILIER SOM LEVDE AV FISKE An Ethnohistory of the Scandinavian Folk Fishermen of Isle Royale National Park Prepared for The National Park Service Midwest Regional Office and Isle Royale National Park By Rebecca S. Toupal Richard W. Stoffle M. Nieves Zedeño January 22, 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE...................................................................................................................... viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS........................................................................................... ix CHAPTER ONE: Study Overview............................................................................... 1 List of Participants ............................................................................................ 2 Schedule of Activities....................................................................................... 3 Structure of the Research.................................................................................. 3 Archival Review ............................................................................................... 3 Oral Histories.................................................................................................... 5 Context of the Report........................................................................................ 5 On-Site Visits.................................................................................................... 9 Analysis and Write-Up .................................................................................... -

Where the Mountain Meets the Moon

Copyright © 2009 by Grace Lin All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Little, Brown Books for Young Readers Hachette Book Group 237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Visit our website at www.HachetteBookGroup.com Little, Brown Books for Young Readers is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc. First eBook Edition: June 2009 The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author. ISBN: 978-0-316-05260-3 Contents COPYRIGHT CHAPTER 1 CHAPTER 2 CHAPTER 3 CHAPTER 4 CHAPTER 5 CHAPTER 6 CHAPTER 7 CHAPTER 8 CHAPTER 9 CHAPTER 10 CHAPTER 11 CHAPTER 12 CHAPTER 13 CHAPTER 14 CHAPTER 15 CHAPTER 16 CHAPTER 17 CHAPTER 18 CHAPTER 19 CHAPTER 20 CHAPTER 21 CHAPTER 22 CHAPTER 23 CHAPTER 24 CHAPTER 25 CHAPTER 26 CHAPTER 27 CHAPTER 28 CHAPTER 29 CHAPTER 30 CHAPTER 31 CHAPTER 32 CHAPTER 33 CHAPTER 34 CHAPTER 35 CHAPTER 36 CHAPTER 37 CHAPTER 38 CHAPTER 39 CHAPTER 40 CHAPTER 41 CHAPTER 42 CHAPTER 43 CHAPTER 44 CHAPTER 45 CHAPTER 46 CHAPTER 47 CHAPTER 48 AUTHOR’S NOTES FOR ROBERT SPECIAL THANKS TO: ALVINA, CONNIE, LIBBY, JANET, MOM, DAD, AND ALEX CHAPTER 1 Far away from here, following the Jade River, there was once a black mountain that cut into the sky like a jagged piece of rough metal. -

The Wishing Fish

GM 2017 2 Contents THEME 1 ............................................................................................................................. 5 WHAT IS A NOVEL ............................................................................................................. 5 FEATURES OF A NOVEL ................................................................................................... 6 ANALYSING A NOVEL ........................................................................................................ 7 THE CRICKET IN TIMES SQUARE .................................................................................... 7 Activity 1: Book Review on Cricket in Times Square ........................................................ 8 Activity 2: The Time Machine ........................................................................................... 9 PRONOUNS ...................................................................................................................... 11 PERSONAL PRONOUNS .................................................................................................. 11 Activity 3: Personal Pronouns ........................................................................................ 12 INDEFINITE PRONOUNS ................................................................................................. 12 Activity 4: Indefinite Pronouns ........................................................................................ 12 PAST TENSE ................................................................................................................... -

THE COOK's WEDDING and OTHER STORIES by Anton Chekhov

THE COOK'S WEDDING AND OTHER STORIES By Anton Chekhov Translated by Constance Garnett Ref: Project Gutenberg http://www.gutenberg.org/ CONTENTS: THE COOK'S WEDDING ..........................................................................................3 SLEEPY......................................................................................................................8 CHILDREN ..............................................................................................................13 THE RUNAWAY .....................................................................................................18 GRISHA....................................................................................................................25 OYSTERS.................................................................................................................28 HOME.......................................................................................................................32 A CLASSICAL STUDENT.......................................................................................40 VANKA....................................................................................................................43 AN INCIDENT .........................................................................................................46 A DAY IN THE COUNTRY.....................................................................................51 BOYS........................................................................................................................57 -

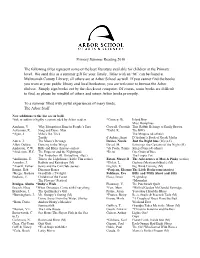

Primary Summer Reading 2010 the Following Titles Represent Some

Primary Summer Reading 2010 The following titles represent some of the best literature available for children at the Primary level. We send this as a summer gift for your family. Titles with an “M” can be found at Multnomah County Library; all others are at Arbor School as well. If you cannot find the books you want at your public library and local bookstore, you are welcome to browse the Arbor shelves. Simply sign books out by the check-out computer. Of course, some books are difficult to find, so please be mindful of others and return Arbor books promptly. To a summer filled with joyful experiences of many kinds, The Arbor Staff New additions to the list are in bold. *title or author is highly recommended by Arbor readers *Cooney, B. Island Boy Miss Rumphius Aardema, V. Why Mosquitoes Buzz in People’s Ears Crowell, Cressida That Rabbit Belongs to Emily Brown Ackerman, K. Song and Dance Man *Dahl, R. The BFG *Agee, J. Milo’s Hat Trick The Minpins (& others) Terrific d’Aulaire, Ingri D’Aulaire’s Book of Greek Myths Aiken, J. The Moon’s Revenge Davies, Nicola Just the Right Size (M) (n.f.) Allen, Debbie Dancing in the Wings Davol, M. Batwings the Curtains of the Night (M) Anderson, C.W. Billy and Blaze (horses--series) *de Paola, Tomie Strega Nona (& others) *Anderson, H.C. The Emperor and the Nightingale *Demi One Grain of Rice The Tinderbox (B. Ibatoulline, illus.) The Empty Pot *Ardizzone, E. Tim to the Lighthouse (Little Tim series) Eaton, Maxwell The Adventures of Max & Pinky (series) Arnosky, J.