From Myra Bradwell to Hillary Clinton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advocacy for Better Implementation of Women's

ADVOCACY FOR BETTER IMPLEMENTATION OF WOMEN’S RIGHTS IN GHANA July 2002 Publié dans – Published on : www.wildaf-ao.org ADVOCACY FOR BETTER IMPLEMENTATION OF WOMEN’S RIGHTS IN GHANA Women in Law and Development in Africa (WiLDAF) Ghana P.O.Box LG 488, Legon Accra Sub Offices : WiLDAF Western Region Legal Awareness Programme, P.O. Box 431, Takoradi WiLDAF Volta Region Legal Awareness Programme P.O Box MA310, Ho ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This document was developed as part of the project: “Sensitisation and Capacity Building of judicial and extrajudicial Stakeholders for sustainable implementation of Women’s’ Rights in West Africa”. WiLDAF -Ghana is, especially, indebted to the European Commission for its financial support which enabled WiLDAF to develop this valuable tool of sensitisation for non legal practitioners who participate in the implementation of women’s rights. WiLDAF also expresses its warm gratitude to all the people who, in one way or the other, contributed to the publishing of this document. Written by DORCAS COKER-APPIAH JOANA FOSTER Cover. Conceptualised by: WiLDAF West African Sub-regional Office, Togo. ( WASRO) Drawn by: Aldus Informatique, Lomé, Togo. Printed by YAMENS PRES LTD 233-32-223222 This document was prepared with the financial support of the European Community. The views hereby presented here are those of WiLDAF/FeDDAF and in no way reflects the official view of the European Community. Publié dans – Published on : www.wildaf-ao.org Contents Foreword .........................................................................................iv -

Circuit Circuit

November 2013 Featured In This Issue The Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals Gets A New Chief Judge, by Brian J. Paul The Changing of the Guard in the Northern District of Illinois, by Jeffrey Cole Address to the Seventh Circuit Bar Association and the Seventh Circuit Judicial Conference Annual Joint TheThe Meeting May 6, 2013, by Senator Richard G. Lugar Through the Eyes of a Juror: A Lawyer's Perspective from Inside the Jury Room, by Karen McNulty Enright The Seventh Circuit Inters "Self-Serving" as an Objection to the Admissibility of Evidence, by Jeffrey Cole My Defining Experience as a Lawyer: Taking a Seventh Circuit Appeal, by Ravi Shankar CirCircuitcuit How 30 Women Changed the Course of the Nation’s Legal and Social History: Commemorating the First National Meeting of Women Lawyers in America, by Gwen Jordan J.D., Ph.D. Common Pleading Deficiencies in RICO Claims, by Andrew C. Erskine You Can Have It Both Ways: Fourth Amendment Standing in the Seventh Circuit, by Christopher Ferro and Marc Kadish RiderRiderT HE J OURNALOFTHE S EVENTH A Life Well Lived, by Steven Lubet C IRCUITIRCUIT B AR A SSOCIATION Significant Amendments to Rule 45, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, to Take Effect on December 1, 2013, by Jeffrey Cole Sealing Portions of the Appellate Record: A Guide for Seventh Circuit Practitioners, by Alexandra L. Newman Changes &Challenges The Circuit Rider In This Issue Letter from the President . .1 The Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals Gets A New Chief Judge, by Brian J. Paul . 2-4 The Changing of the Guard in the Northern District of Illinois, by Jeffrey Cole . -

Self-Reflection Within the Academy: the Absence of Women in Constitutional Jurisprudence Karin Mika

Hastings Women’s Law Journal Volume 9 | Number 2 Article 6 7-1-1998 Self-Reflection within the Academy: The Absence of Women in Constitutional Jurisprudence Karin Mika Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hwlj Recommended Citation Karin Mika, Self-Reflection within the Academy: The Absence of Women in Constitutional Jurisprudence, 9 Hastings Women's L.J. 273 (1998). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hwlj/vol9/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Women’s Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. & Self-Reflection within the Academy: The Absence of Women in Constitutional Jurisprudence Karin Mika* One does not have to be an ardent feminist to recognize that the con tributions of women in our society have been largely unacknowledged by both history and education. l Individuals need only be reasonably attentive to recognize there is a similar absence of women within the curriculum presented in a standard legal education. If one reads Elise Boulding's The Underside of History2 it is readily apparent that there are historical links between the achievements of women and Nineteenth century labor reform, Abolitionism, the Suffrage Movement and the contemporary view as to what should be protected First Amendment speech? Despite Boulding's depiction, treatises and texts on both American Legal History-and those tracing the development of Constitutional Law-present these topics as distinct and without any significant intersection.4 The contributions of women within all of these movements, except perhaps for the rarely men- *Assistant Director, Legal Writing Research and Advocacy Cleveland-Marshall College of Law. -

The Woman-Slave Analogy: Rhetorical Foundations in American

The Woman-Slave Analogy: Rhetorical Foundations in American Culture, 1830-1900 Ana Lucette Stevenson BComm (dist.), BA (HonsI) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2014 School of History, Philosophy, Religion and Classics I Abstract During the 1830s, Sarah Grimké, the abolitionist and women’s rights reformer from South Carolina, stated: “It was when my soul was deeply moved at the wrongs of the slave that I first perceived distinctly the subject condition of women.” This rhetorical comparison between women and slaves – the woman-slave analogy – emerged in Europe during the seventeenth century, but gained peculiar significance in the United States during the nineteenth century. This rhetoric was inspired by the Revolutionary Era language of liberty versus tyranny, and discourses of slavery gained prominence in the reform culture that was dominated by the American antislavery movement and shared among the sisterhood of reforms. The woman-slave analogy functioned on the idea that the position of women was no better – nor any freer – than slaves. It was used to critique the exclusion of women from a national body politic based on the concept that “all men are created equal.” From the 1830s onwards, this analogy came to permeate the rhetorical practices of social reformers, especially those involved in the antislavery, women’s rights, dress reform, suffrage and labour movements. Sarah’s sister, Angelina, asked: “Can you not see that women could do, and would do a hundred times more for the slave if she were not fettered?” My thesis explores manifestations of the woman-slave analogy through the themes of marriage, fashion, politics, labour, and sex. -

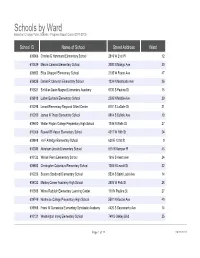

Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012)

Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012) School ID Name of School Street Address Ward 609966 Charles G Hammond Elementary School 2819 W 21st Pl 12 610539 Marvin Camras Elementary School 3000 N Mango Ave 30 609852 Eliza Chappell Elementary School 2135 W Foster Ave 47 609835 Daniel R Cameron Elementary School 1234 N Monticello Ave 26 610521 Sir Miles Davis Magnet Elementary Academy 6730 S Paulina St 15 609818 Luther Burbank Elementary School 2035 N Mobile Ave 29 610298 Lenart Elementary Regional Gifted Center 8101 S LaSalle St 21 610200 James N Thorp Elementary School 8914 S Buffalo Ave 10 609680 Walter Payton College Preparatory High School 1034 N Wells St 27 610056 Roswell B Mason Elementary School 4217 W 18th St 24 609848 Ira F Aldridge Elementary School 630 E 131st St 9 610038 Abraham Lincoln Elementary School 615 W Kemper Pl 43 610123 William Penn Elementary School 1616 S Avers Ave 24 609863 Christopher Columbus Elementary School 1003 N Leavitt St 32 610226 Socorro Sandoval Elementary School 5534 S Saint Louis Ave 14 609722 Manley Career Academy High School 2935 W Polk St 28 610308 Wilma Rudolph Elementary Learning Center 110 N Paulina St 27 609749 Northside College Preparatory High School 5501 N Kedzie Ave 40 609958 Frank W Gunsaulus Elementary Scholastic Academy 4420 S Sacramento Ave 14 610121 Washington Irving Elementary School 749 S Oakley Blvd 25 Page 1 of 28 09/23/2021 Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012) 610352 Durkin Park Elementary School -

Gender and Social Inclusion Analysis (Gsia) Usaidlaos Legal Aid Support

GENDER AND SOCIAL INCLUSION ANALYSIS (GSIA) USAID LAOS LEGAL AID SUPPORT PROGRAM The Asia Foundation Vientiane, Lao PDR 26 July 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................... i Acronyms ......................................................................................................................................... iii 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................1 1.1 Background .......................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 The Laos Legal Aid Support Program................................................................................................... 1 1.2 This Report ........................................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Methodology and Coverage ................................................................................................................ 2 1.4 Limitations ........................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Contextual Analysis ........................................................................................................................3 2.1 Gender Equality .................................................................................................................................. -

Beijing, Backlash, and the Future of Women's Human Rights

C o m m e n t a r y BEIJING, BACKLASH, AND THE FUTURE OF WOMEN'S HUMAN RIGHTS Charlotte Bunch l7he United Nations (UN) FourthWorld Conference on Women, held in Beijing this September 1995, occurs at a historical juncture for women. As we increasingly make our voices heard globally, the urgent need for women to be an integral part of the decision-making processes shaping the twenty-first century has never been more pressing. Indeed, the experience of women is central to a multitude of the world's concerns ranging from religious fundamentalism and chauvinistic nationalism to the global economy. As the old world ordercontinues its process of disintegration, transition, and re-organization, the opportunity for women to be heard is enhanced precisely because new alternatives are so badly needed. However, at the same time, there looms a dangerthat women's gains in the twentieth century will be turned back by religious fundamentalist forces and/or narrowly defined patriarchal nationalisms, which seek cohesion by returning women to traditional roles. In confronting these forces, women's voices must be heard. The first UN Decade for Women, from 1976 to 1985, helped legitimize women's projects and demands for greater participation in civil society at the local, national, and inter- national levels. In the decade since the 1985 World Confer- Charlotte Bunch is Director of the Center for Women's Global Leader- ship at Rutgers University and a Professor in the Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy at Rutgers University, New Jersey. Please send correspondence to Charlotte Bunch, Center for Women's Global Leadership, Douglass College, 27 Clifton Avenue, New Brunswick, New Jersey 08903, USA. -

Votes for Women! Celebrating New York’S Suffrage on November 6, 1917, New York State Passed the Referendum for Women’S Suffrage

New York State’s Women’s Suffrage History Votes for Women! Celebrating New York’s Suffrage On November 6, 1917, New York State passed the referendum for women’s suffrage. This victory was an important event for New York State and the nation. Suffrage in New York State signaled that the national passage of women’s suffrage would soon follow, and in August 1920, “Votes for Women” were constitutionally guaranteed. Although women began asserting their independence long before, the irst coordinated work for women’s suffrage began at the Seneca Falls convention in 1848. The convention served as a catalyst for debates and action. Women like Susan B. Anthony and Matilda Joslyn Gage organized and rallied for support of women’s suffrage throughout upstate New York. Others, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Amelia Bloomer supported the effort through the use of their pens. Stanton wrote letters, speeches, and articles while Bloomer published the irst newspaper for women, The Lily, in 1849. These combined efforts culminated in the creation of the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA). By the dawn of the twentieth century, the political and social landscape was much different in New York State than ifty years before. The state experienced dramatic advances in industry and urban growth. Several large waves of immigrants settled throughout the state and now more and more women were working outside of the home. Reformers concerns shifted to labor issues, health care, and temperance. New reformers like Harriot Stanton Blatch and Carrie Chapman Catt used new tactics such as marches, meetings, and signed petitions to show that New Yorkers wanted suffrage. -

[, F/ V C Edna Hammer Cooley 1986 APPROVAL SHEET

WOMEN IN AMERICAN THEATRE, 1850-1870: A STUDY IN PROFESSIONAL EQUITY by Edna Hammer Cooley I i i Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland in parti.al fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ~ /, ,, ·' I . 1986 I/ '/ ' ·, Cop~ I , JI ,)() I co uI (~; 1 ,[, f/ v c Edna Hammer Cooley 1986 APPROVAL SHEET Title of Dissertation: Women in American Theatre, 1850-1870: A Study in Professional Equity Name of Candidate: Edna Hammer Cooley Doctor of Philosophy, 1986 Dissertation and Approved: Dr. Roger Meersman Professor Dept. of Communication Arts & Theatre Date Approved: .;;Jo .i? p ,vt_,,/ /9Y ,6 u ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: Women in American Theatre, 1850- 1870~ A Study_ in Professional Equi!:Y Edna Hammer Cooley, Doctor of Philosophy, 1986 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Roger Meersman Professor of Communication Arts and Theatre Department of Communication Arts and Theatre This study supports the contention that women in the American theatre from 1850 to 1870 experienced a unique degree of professional equity with men in the atre. The time-frame has been selected for two reasons: (1) actresses active after 1870 have been the subject of several dissertations and scholarly studies, while relatively little research has been completed on women active on the American stage prior to 1870, and (2) prior to 1850 there was limited theatre activity in this country and very few professional actresses. A general description of mid-nineteenth-century theatre and its social context is provided, including a summary of major developments in theatre in New York and other cities from 1850 to 1870, discussions of the star system, the combination company, and the mid-century audience. -

The 19Th Amendment

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Women Making History: The 19th Amendment Women The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation. —19th Amendment to the United States Constitution In 1920, after decades of tireless activism by countless determined suffragists, American women were finally guaranteed the right to vote. The year 2020 marks the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. It was ratified by the states on August 18, 1920 and certified as an amendment to the US Constitution on August 26, 1920. Developed in partnership with the National Park Service, this publication weaves together multiple stories about the quest for women’s suffrage across the country, including those who opposed it, the role of allies and other civil rights movements, who was left behind, and how the battle differed in communities across the United States. Explore the complex history and pivotal moments that led to ratification of the 19th Amendment as well as the places where that history happened and its continued impact today. 0-31857-0 Cover Barcode-Arial.pdf 1 2/17/20 1:58 PM $14.95 ISBN 978-1-68184-267-7 51495 9 781681 842677 The National Park Service is a bureau within the Department Front cover: League of Women Voters poster, 1920. of the Interior. It preserves unimpaired the natural and Back cover: Mary B. Talbert, ca. 1901. cultural resources and values of the National Park System for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this work future generations. -

Iowa's Role in the Suffrage Movement

Lesson #5 Commemorating the Centennial Of the 19th Amendment Designed for Grades 9-12 6 Lesson Unit/Each Lesson 2 Days Based on Iowa Social Studies Standards Iowa’s Role in the Suffrage Movement Unit Question: What is the 19th Amendment, and how has it influenced the United States? Supporting Question: How was Iowa involved in the promotion of and passage of the 19th Amendment? Lesson Overview The lesson will highlight suffrage leaders with Iowa ties and events in the state leading up to the passage of the 19th Amendment. Lesson Objectives and Targets Students will… 1. take note of key events in Iowa’s path to achieve women’s enfranchisement. 2. read provided biographical entries on selected Iowa suffrage leaders. 3. read and review the University of Iowa Library Archives selections on suffrage, selections from the Carrie Chapman Catt Center for Women and Politics website, and the Iowa Women’s Hall of Fame coverage about Iowa suffragists and contemporary Iowa women leaders.. Useful Terms and Background ● Iowa Organizations - Iowa Woman Suffrage Association (IWSA), Iowa Equal Suffrage Association (IESA) along with several local and state clubs of support ● National suffrage leaders with Iowa roots - Amelia Jenks Bloomer & Carrie Chapman Catt ● Noted Iowa suffragists included in the Iowa Women’s Hall of Fame ● Suffrage activities throughout the state ● Early state attempts for amendments along with Iowa ratification of the 19th Amendment Lesson Procedure Day 1 Teacher Notes for Day 1 1. Point out that lesson materials have been selected from three unique Iowa sources: the University of Iowa Library Archives and the websites for Iowa State University’s Carrie Chapman Catt Center for Women and Politics and the Iowa Women’s Hall of Fame. -

Resolution 1325 and Post Cold-War Feminist Politics

Resolution 1325 and post Cold-War Feminist Politics Paper under review with the International Feminist Journal of Politics – please do not circulate or quote without consulting the author. [email protected] ABSTRACT Social movement scholars credit feminist transnational advocacy networks with putting violence against women on the UN security agenda, as evidenced by resolution 1325 and numerous other UN Security Council statements on gender, peace, and security. Such accounts neglect the significance of super power politics for shaping the aims of women’s bureaucracies and NGOs in the UN system. This article highlights how the fall of the Soviet Union transformed the delineation of ‘women’s issues’ at the United Nations and calls attention to the extent that the new focus upon ‘violence against women’ has been shaped by the post Cold War US global policing practices. Resolution 1325’s call for gender-mainstreaming of peacekeeping operations reflects the tension between feminist advocates’ increased influence in security discourse and continuing reports of peacekeeper perpetrated sexual violence, abuse and exploitation. Key Words: Transnational advocacy networks, Cold War, New Wars, Democratization, Peacekeeping, Human Rights, Feminism, Violence against Women, United Nations. In October 2000, the unanimous passage of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 linked gender, peace, and security and recognized the need to ‘mainstream a gender perspective in peacekeeping operations.’ The Resolution authorizes monitoring of peacekeeping operations by gender experts and condemns military sexual violence. As a policy artifact this Resolution gives evidence of startling tensions in the gender politics of mainstream international security discourse in the final years of the twentieth century.