Self-Reflection Within the Academy: the Absence of Women in Constitutional Jurisprudence Karin Mika

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Illinois State Museum Announces Women'

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE For more information contact: March 23, 2021 Jamila Wicks C: 706-207-7836 [email protected] Illinois State Museum Announces Women's History Series and Trail Walk in the Footsteps of Illinois Women and Listen to Their Stories SPRINGFIELD, Ill. — As part of Women’s History Month, the Illinois State Museum (ISM) today announced the launch of its “In Her Footsteps Series” beginning this March through June. Each program in the series will occur online on the fourth Tuesday of the month from 6:30 p.m. to 7:00 p.m. The series will feature Illinois women and their contributions to history, culture, and society. Its aim is to encourage Illinoisans to learn more about women’s history in their region and perhaps travel, virtually or in person, to learn more about their stories. “The ‘In Her Footsteps Series’ is a chance for the Illinois State Museum to tell stories of women who called Illinois home,” said ISM Director of Interpretation Jennifer Edginton. “We’re focusing on women whom you may have heard of before, but not sure how exactly you heard of them. We’re telling diverse stories that bring to life the dynamic history of Illinois.” Additionally, the Museum will include each of these women and other female historical figures on its new “In Her Footsteps Illinois Women’s History Trail” website scheduled to launch in May. The website will pinpoint locations across the state connected to women who have contributed to Illinois history. It will summarize each woman’s story and provide information on historic sites and markers that the public can visit. -

Circuit Circuit

November 2013 Featured In This Issue The Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals Gets A New Chief Judge, by Brian J. Paul The Changing of the Guard in the Northern District of Illinois, by Jeffrey Cole Address to the Seventh Circuit Bar Association and the Seventh Circuit Judicial Conference Annual Joint TheThe Meeting May 6, 2013, by Senator Richard G. Lugar Through the Eyes of a Juror: A Lawyer's Perspective from Inside the Jury Room, by Karen McNulty Enright The Seventh Circuit Inters "Self-Serving" as an Objection to the Admissibility of Evidence, by Jeffrey Cole My Defining Experience as a Lawyer: Taking a Seventh Circuit Appeal, by Ravi Shankar CirCircuitcuit How 30 Women Changed the Course of the Nation’s Legal and Social History: Commemorating the First National Meeting of Women Lawyers in America, by Gwen Jordan J.D., Ph.D. Common Pleading Deficiencies in RICO Claims, by Andrew C. Erskine You Can Have It Both Ways: Fourth Amendment Standing in the Seventh Circuit, by Christopher Ferro and Marc Kadish RiderRiderT HE J OURNALOFTHE S EVENTH A Life Well Lived, by Steven Lubet C IRCUITIRCUIT B AR A SSOCIATION Significant Amendments to Rule 45, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, to Take Effect on December 1, 2013, by Jeffrey Cole Sealing Portions of the Appellate Record: A Guide for Seventh Circuit Practitioners, by Alexandra L. Newman Changes &Challenges The Circuit Rider In This Issue Letter from the President . .1 The Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals Gets A New Chief Judge, by Brian J. Paul . 2-4 The Changing of the Guard in the Northern District of Illinois, by Jeffrey Cole . -

July 1979 • Volume Iv • Number Vi

THE FASTEST GROWING CHURCH IN THE WORLD by Brother Keith E. L'Hommedieu, D.D. quite safe tosay that ofall the organized religious sects on the current scene, one church in particular stands above all in its unique approach to religion. The Universal LifeChurch is the onlyorganized church in the world withno traditional religious doctrine. Inthe words of Kirby J. Hensley,founder, "The ULC only believes in what is right, and that all people have the right to determine what beliefs are for them, as long as Brother L 'Hommed,eu 5 Cfla,r,nan right ol the Board of Trusteesof the Sa- they do not interferewith the rights ofothers.' cerdotal Orderof the Un,versalL,fe andserves on the Board of O,rec- Reverend Hensley is the leader ofthe worldwide torsOf tOe fnternahOna/ Uns'ersaf Universal Life Church with a membership now L,feChurch, Inc. exceeding 7 million ordained ministers of all religious bileas well as payfor traveland educational expenses. beliefs. Reverend Hensleystarted the church in his NOne ofthese expenses are reported as income to garage by ordaining ministers by mail. During the the IRS. Recently a whole town in Hardenburg. New 1960's, he traveled all across the country appearing York became Universal Life ministers and turned at college rallies held in his honor where he would their homes into religious retreatsand monasteries perform massordinations of thousands of people at a thereby relieving themselves of property taxes, at time. These new ministers were then exempt from least until the state tries to figure out what to do. being inducted into the armed forces during the Churches enjoycertain othertax benefits over the undeclared Vietnam war. -

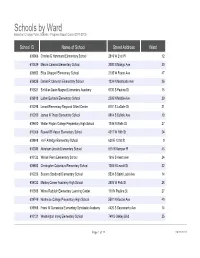

Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012)

Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012) School ID Name of School Street Address Ward 609966 Charles G Hammond Elementary School 2819 W 21st Pl 12 610539 Marvin Camras Elementary School 3000 N Mango Ave 30 609852 Eliza Chappell Elementary School 2135 W Foster Ave 47 609835 Daniel R Cameron Elementary School 1234 N Monticello Ave 26 610521 Sir Miles Davis Magnet Elementary Academy 6730 S Paulina St 15 609818 Luther Burbank Elementary School 2035 N Mobile Ave 29 610298 Lenart Elementary Regional Gifted Center 8101 S LaSalle St 21 610200 James N Thorp Elementary School 8914 S Buffalo Ave 10 609680 Walter Payton College Preparatory High School 1034 N Wells St 27 610056 Roswell B Mason Elementary School 4217 W 18th St 24 609848 Ira F Aldridge Elementary School 630 E 131st St 9 610038 Abraham Lincoln Elementary School 615 W Kemper Pl 43 610123 William Penn Elementary School 1616 S Avers Ave 24 609863 Christopher Columbus Elementary School 1003 N Leavitt St 32 610226 Socorro Sandoval Elementary School 5534 S Saint Louis Ave 14 609722 Manley Career Academy High School 2935 W Polk St 28 610308 Wilma Rudolph Elementary Learning Center 110 N Paulina St 27 609749 Northside College Preparatory High School 5501 N Kedzie Ave 40 609958 Frank W Gunsaulus Elementary Scholastic Academy 4420 S Sacramento Ave 14 610121 Washington Irving Elementary School 749 S Oakley Blvd 25 Page 1 of 28 09/23/2021 Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012) 610352 Durkin Park Elementary School -

The Role of Political Protest

4.12 The Role of Political Protest Standard 4.12: The Role of Political Protest Examine the role of political protest in a democracy. (Massachusetts Curriculum Framework for History and Social Studies) [8.T4.12] FOCUS QUESTION: What are the Different Ways That Political Protest Happens in a Democracy? Building Democracy for All 1 Rosa Parks being fingerprinted by Deputy Sheriff D.H. Lackey after being arrested for boycotting public transportation, Montgomery, Alabama, February, 1956 Public domain photograph from The Plain Dealer newspaper The right to protest is essential in a democracy. It is a means for people to express dissatisfaction with current situations and assert demands for social, political, and economic change. Protests make change happen and throughout the course of United States history it has taken sustained protests over long periods of time to bring about substantive change in governmental policies and the lives of people. Protest takes political courage as well, the focal point of Standard 4.11 in this book. The United States emerged from American protests against England’s colonial rule. Founded in 1765, the Sons of Liberty and the Daughters of Liberty organized protests against what they Building Democracy for All 2 considered to be unfair British laws. In 1770, the Boston Massacre happened when British troops fired on protestors. Then, there was the Boston Tea Party (December 16, 1773) when 60 Massachusetts colonists dumped 342 chests of tea—enough to make 19 million cups—into Boston Harbor. In 1775, there were armed -

The Civil War in the American Ruling Class

tripleC 16(2): 857-881, 2018 http://www.triple-c.at The Civil War in the American Ruling Class Scott Timcke Department of Literary, Cultural and Communication Studies, The University of The West Indies, St. Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago, [email protected] Abstract: American politics is at a decisive historical conjuncture, one that resembles Gramsci’s description of a Caesarian response to an organic crisis. The courts, as a lagging indicator, reveal this longstanding catastrophic equilibrium. Following an examination of class struggle ‘from above’, in this paper I trace how digital media instruments are used by different factions within the capitalist ruling class to capture and maintain the commanding heights of the American social structure. Using this hegemony, I argue that one can see the prospect of American Caesarism being institutionally entrenched via judicial appointments at the Supreme Court of the United States and other circuit courts. Keywords: Gramsci, Caesarism, ruling class, United States, hegemony Acknowledgement: Thanks are due to Rick Gruneau, Mariana Jarkova, Dylan Kerrigan, and Mark Smith for comments on an earlier draft. Thanks also go to the anonymous reviewers – the work has greatly improved because of their contributions. A version of this article was presented at the Local Entanglements of Global Inequalities conference, held at The University of The West Indies, St. Augustine in April 2018. 1. Introduction American politics is at a decisive historical juncture. Stalwarts in both the Democratic and the Republican Parties foresee the end of both parties. “I’m worried that I will be the last Republican president”, George W. Bush said as he recoiled at the actions of the Trump Administration (quoted in Baker 2017). -

Online Media and the 2016 US Presidential Election

Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Faris, Robert M., Hal Roberts, Bruce Etling, Nikki Bourassa, Ethan Zuckerman, and Yochai Benkler. 2017. Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election. Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society Research Paper. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33759251 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA AUGUST 2017 PARTISANSHIP, Robert Faris Hal Roberts PROPAGANDA, & Bruce Etling Nikki Bourassa DISINFORMATION Ethan Zuckerman Yochai Benkler Online Media & the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This paper is the result of months of effort and has only come to be as a result of the generous input of many people from the Berkman Klein Center and beyond. Jonas Kaiser and Paola Villarreal expanded our thinking around methods and interpretation. Brendan Roach provided excellent research assistance. Rebekah Heacock Jones helped get this research off the ground, and Justin Clark helped bring it home. We are grateful to Gretchen Weber, David Talbot, and Daniel Dennis Jones for their assistance in the production and publication of this study. This paper has also benefited from contributions of many outside the Berkman Klein community. The entire Media Cloud team at the Center for Civic Media at MIT’s Media Lab has been essential to this research. -

Important Women in United States History (Through the 20Th Century) (A Very Abbreviated List)

Important Women in United States History (through the 20th century) (a very abbreviated list) 1500s & 1600s Brought settlers seeking religious freedom to Gravesend at New Lady Deborah Moody Religious freedom, leadership 1586-1659 Amsterdam (later New York). She was a respected and important community leader. Banished from Boston by Puritans in 1637, due to her views on grace. In Religious freedom of expression 1591-1643 Anne Marbury Hutchinson New York, natives killed her and all but one of her children. She saved the life of Capt. John Smith at the hands of her father, Chief Native and English amity 1595-1617 Pocahontas Powhatan. Later married the famous John Rolfe. Met royalty in England. Thought to be North America's first feminist, Brent became one of the Margaret Brent Human rights; women's suffrage 1600-1669 largest landowners in Maryland. Aided in settling land dispute; raised armed volunteer group. One of America's first poets; Bradstreet's poetry was noted for its Anne Bradstreet Poetry 1612-1672 important historic content until mid-1800s publication of Contemplations , a book of religious poems. Wife of prominent Salem, Massachusetts, citizen, Parsons was acquitted Mary Bliss Parsons Illeged witchcraft 1628-1712 of witchcraft charges in the most documented and unusual witch hunt trial in colonial history. After her capture during King Philip's War, Rowlandson wrote famous Mary Rowlandson Colonial literature 1637-1710 firsthand accounting of 17th-century Indian life and its Colonial/Indian conflicts. 1700s A Georgia woman of mixed race, she and her husband started a fur trade Trading, interpreting 1700-1765 Mary Musgrove with the Creeks. -

A HISTORICAL COMPARISON of FEMALE POLITICAL INVOLVEMENT in EARLY NATIVE AMERICA and the US O

42838-elo_13 Sheet No. 169 Side B 12/23/2020 10:41:31 SULLIVAN_FINAL (APPROVED).DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 12/21/20 6:54 PM THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING A WOMAN:AHISTORICAL COMPARISON OF FEMALE POLITICAL INVOLVEMENT IN EARLY NATIVE AMERICA AND THE U.S. SPENSER M. SULLIVAN∗ “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”1 I. INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................................................................335 II. REPUBLICAN MOTHERHOOD AND THE “SEPARATE SPHERES” DOCTRINE............................................................................................................................................338 A. Women in the Pre-Revolutionary Era ..............................338 B. The Role of Women in the U.S. Constitution.................339 C. Enlightenment Influences................................................340 D. Republican Mothers.........................................................341 III. WOMEN’S CITIZENSHIP AND THE BARRIERS TO LEGAL EQUALITY....343 A. Defining Female Citizenship in the Founding Era .........343 B. Women’s Ownership of Property–the Feme Covert Conundrum....................................................................344 C. Martin v. Commonwealth: The Rights of the Feme Covert .............................................................................346 D. Bradwell v. Illinois: The Privileges and Immunities of 42838-elo_13 Sheet No. 169 Side B 12/23/2020 -

DVS Commissioner on Women's History Month 2021

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: March 25, 2021 CONTACT: [email protected]; 212-416-5250 Statement from Department of Veterans’ Services Commissioner James Hendon on Women’s History Month 2021 New York City Department of Veterans’ Services Commissioner James Hendon released the following remarks about honoring the contributions of Women in American history. “Every March, we honor the contributions of women throughout our history and the ongoing struggle to achieve equality. In time’s eternal passage, it was barely one century ago that American women obtained the right to vote, and it was only months ago that Kamala Harris, the first woman Vice-President, was sworn into office. Even as women formed our nation’s backbone, they were forced to stand in the shadows of men. Yet, despite this, they were often the ones who agitated for change and who led the charge for continual progress. In their times, Susan B. Anthony, Harriet Tubman, Mother Jones, and Ida B. Wells rowed against the societal grain. They were mocked for their beliefs on suffrage, abolition, worker’s rights, and racial justice. Today, however, we revere them for planting the seeds that have reaped a harvest from which future generations have benefited. The military has also not been immune to the prejudices of the ages. Women have long played an essential role in our nation’s defense. From Concord to Kandahar, from Margaret “Captain Molly” Corbin to General Ann Dunwoody, women patriots have fought for our freedoms even while facing harassment and a deck that was stacked against them. Today, roughly fifteen percent of America’s Active Duty Armed Forces are women. -

![INSTITUTION Pennsylvania State Dept. of Education, Harrisburg. PUB DATE [84] NOTE 104P](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2462/institution-pennsylvania-state-dept-of-education-harrisburg-pub-date-84-note-104p-892462.webp)

INSTITUTION Pennsylvania State Dept. of Education, Harrisburg. PUB DATE [84] NOTE 104P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 253 618 UD 024 065 AUTHOR Waters, Bertha S., Comp. TITLE Women's History Week in Pennsylvania. March 3-9, 1985. INSTITUTION Pennsylvania State Dept. of Education, Harrisburg. PUB DATE [84] NOTE 104p. PUB TYPE Guides - Non-Classroom Use, (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Biographies; tt dV Activities; Disabilities; Elementary Sec adary Education; *Females; *Government (Administrative body); *Leaders; Learning Activities; *Politics; Resour,e Materials; Sex Discrimination; *United States History IDENTIFIERS *National Womens History Week Project; *Pennsylvania ABSTRACT The materials in this resource handbook are for the use of Pennsylvania teachers in developing classroom activities during National Women's History Week. The focus is on womenWho, were notably active in government and politics (primarily, but not necessarily in Pennsylvania). The following women are profiled: Hallie Quinn Brown; Mary Ann Shadd Cary; Minerva Font De Deane; Katharine Drexel (Mother Mary Katharine); Jessie Redmon Fauset; Mary Harris "Mother" Jones; Mary Elizabeth Clyens Lease; Mary Edmonia Lewis; Frieda Segelke Miller; Madame Montour; Gertrude Bustill Mossell; V nnah Callowhill Penn; Frances Perkins; Mary Roberts Rinehart; i_hel Watersr Eleanor Roosevelt (whose profile is accompanied by special activity suggestions and learning materials); Ana Roque De Duprey; Fannie Lou Hamer; Frances Ellen Watkins Harper; Pauli Murray; Alice Paul; Jeanette Rankin; Mary Church Terrell; Henrietta Vinton Davis; Angelina Weld Grimke; Helene Keller; Emma Lazarus; and Anna May Wong. Also provided are a general discussion of important Pennsylvania women in politics and government, brief profiles of Pennsylvania women currently holding Statewide office, supplementary information on women in Federal politics, chronological tables, and an outline of major changes in the lives of women during this century. -

What's the Big Deal About Freedom TRIVIA CARDS

What’s The Big Deal About Freedom TRIVIA CARDS Print, cut out, and fold these trivia cards to quiz your friends or yourself! WHAT’S THE BIG DEAL ABOUT 1 WHAT’S THE BIG DEAL ABOUT 2 Which founding father Which freedoms are wrote his name extra big protected in the first on the Declaration of amendment? Independence? a) Freedom of speech a) George Washington b) Freedom of religion b) James Madison c) Freedom of assembly c) John Hancock d) All of the above d) Alexander Hamilton Ruby Shamir ★ Matt Faulkner Ruby Shamir ★ Matt Faulkner WHAT’S THE BIG DEAL ABOUT 3 WHAT’S THE BIG DEAL ABOUT 4 How many times did Which courageous escaped slave Harriet Tubman return to crisscrossed the country collecting the South after escaping supplies for black Union soldiers from slavery to help other and speaking out against slavery slaves escape to freedom? and for the right of women to vote? a) Sojourner Truth a) Two b) Frederick Douglass b) Six c) Henry “Box” Brown c) Nineteen d) Nat Turner d) None Ruby Shamir ★ Matt Faulkner Ruby Shamir ★ Matt Faulkner ANSWERS: 1) c, 2) d, 3) c, 4) a, 5) b, 6) b, 7) d, 8) c, 9) d, 10) a, 11) b, 12) d What’s The Big Deal About Freedom TRIVIA CARDS Print, cut out, and fold these trivia cards to quiz your friends or yourself! WHAT’S THE BIG DEAL ABOUT 5 WHAT’S THE BIG DEAL ABOUT 6 Which amendment Who led the Uprising of the granted citizenship to 20,000, a strike comprised former slaves? of mostly young women a) Thirteenth workers, when she was 23? b) Fourteenth a) Mother Jones c) Fifteenth b) Clara Lemlich d) Nineteenth c) Susan B.