Circuit Circuit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Self-Reflection Within the Academy: the Absence of Women in Constitutional Jurisprudence Karin Mika

Hastings Women’s Law Journal Volume 9 | Number 2 Article 6 7-1-1998 Self-Reflection within the Academy: The Absence of Women in Constitutional Jurisprudence Karin Mika Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hwlj Recommended Citation Karin Mika, Self-Reflection within the Academy: The Absence of Women in Constitutional Jurisprudence, 9 Hastings Women's L.J. 273 (1998). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hwlj/vol9/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Women’s Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. & Self-Reflection within the Academy: The Absence of Women in Constitutional Jurisprudence Karin Mika* One does not have to be an ardent feminist to recognize that the con tributions of women in our society have been largely unacknowledged by both history and education. l Individuals need only be reasonably attentive to recognize there is a similar absence of women within the curriculum presented in a standard legal education. If one reads Elise Boulding's The Underside of History2 it is readily apparent that there are historical links between the achievements of women and Nineteenth century labor reform, Abolitionism, the Suffrage Movement and the contemporary view as to what should be protected First Amendment speech? Despite Boulding's depiction, treatises and texts on both American Legal History-and those tracing the development of Constitutional Law-present these topics as distinct and without any significant intersection.4 The contributions of women within all of these movements, except perhaps for the rarely men- *Assistant Director, Legal Writing Research and Advocacy Cleveland-Marshall College of Law. -

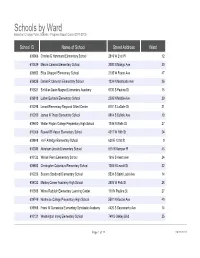

Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012)

Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012) School ID Name of School Street Address Ward 609966 Charles G Hammond Elementary School 2819 W 21st Pl 12 610539 Marvin Camras Elementary School 3000 N Mango Ave 30 609852 Eliza Chappell Elementary School 2135 W Foster Ave 47 609835 Daniel R Cameron Elementary School 1234 N Monticello Ave 26 610521 Sir Miles Davis Magnet Elementary Academy 6730 S Paulina St 15 609818 Luther Burbank Elementary School 2035 N Mobile Ave 29 610298 Lenart Elementary Regional Gifted Center 8101 S LaSalle St 21 610200 James N Thorp Elementary School 8914 S Buffalo Ave 10 609680 Walter Payton College Preparatory High School 1034 N Wells St 27 610056 Roswell B Mason Elementary School 4217 W 18th St 24 609848 Ira F Aldridge Elementary School 630 E 131st St 9 610038 Abraham Lincoln Elementary School 615 W Kemper Pl 43 610123 William Penn Elementary School 1616 S Avers Ave 24 609863 Christopher Columbus Elementary School 1003 N Leavitt St 32 610226 Socorro Sandoval Elementary School 5534 S Saint Louis Ave 14 609722 Manley Career Academy High School 2935 W Polk St 28 610308 Wilma Rudolph Elementary Learning Center 110 N Paulina St 27 609749 Northside College Preparatory High School 5501 N Kedzie Ave 40 609958 Frank W Gunsaulus Elementary Scholastic Academy 4420 S Sacramento Ave 14 610121 Washington Irving Elementary School 749 S Oakley Blvd 25 Page 1 of 28 09/23/2021 Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012) 610352 Durkin Park Elementary School -

A HISTORICAL COMPARISON of FEMALE POLITICAL INVOLVEMENT in EARLY NATIVE AMERICA and the US O

42838-elo_13 Sheet No. 169 Side B 12/23/2020 10:41:31 SULLIVAN_FINAL (APPROVED).DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 12/21/20 6:54 PM THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING A WOMAN:AHISTORICAL COMPARISON OF FEMALE POLITICAL INVOLVEMENT IN EARLY NATIVE AMERICA AND THE U.S. SPENSER M. SULLIVAN∗ “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”1 I. INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................................................................335 II. REPUBLICAN MOTHERHOOD AND THE “SEPARATE SPHERES” DOCTRINE............................................................................................................................................338 A. Women in the Pre-Revolutionary Era ..............................338 B. The Role of Women in the U.S. Constitution.................339 C. Enlightenment Influences................................................340 D. Republican Mothers.........................................................341 III. WOMEN’S CITIZENSHIP AND THE BARRIERS TO LEGAL EQUALITY....343 A. Defining Female Citizenship in the Founding Era .........343 B. Women’s Ownership of Property–the Feme Covert Conundrum....................................................................344 C. Martin v. Commonwealth: The Rights of the Feme Covert .............................................................................346 D. Bradwell v. Illinois: The Privileges and Immunities of 42838-elo_13 Sheet No. 169 Side B 12/23/2020 -

Company Now Generating Its Product

In Memory Of Jacksonville WPD Nabs Teacher Landing Shooting Victims On Drug Counts A3 Herald-THE Advocate HARDEE COUNTY’S HOMETOWN COVERAGE 118th Year No. 40 2 Sections www.TheHeraldAdvocate.com 93¢ Plus 7¢ Sales Tax Thursday, August 30, 2018 It’s Flores; Evers Vs. Horton By CYNTHIA KRAHL the Republican Party’s nomina- was 44 percent to 39.6. chance to go on to November. the November election,” he ily captured Hardee, with 1,885 Of The Herald-Advocate tion with 1,440 votes to Birge’s The third contender, James F. “I would like to thank every- said. votes to Stephen Pincket’s With little more than 31 per- 1,012. Pyle, took 601 of the ballots, or body for their support,” he said In regional races, Hardee 1,295. cent of Hardee County’s regis- And in the battle for the 16.3 percent of the votes. Tuesday night. “This was very County voters favored Melissa Circuit-wide results were not tered voters casting ballots in bench, Ken Evers took an early Flores will go on to fight De- humbling. We still have lots of Gravitt for Group 10 circuit in at press time. the Primary Election, an in- lead, which slipped as returns mocrat Ralph Arce in the Gen- work to do. I hope voters will judge for the 10th Judicial Cir- State races brought some un- cumbent county commissioner continued to come in but held eral Election on Nov. 6, with continue to support me in the cuit, which includes Hardee, expected upsets for Hardee was ousted and a runoff was long enough to put him into a the winner taking the District 2 General Election.” Highlands and Polk counties. -

Some Dumb Girl Syndrome: Challenging and Subverting Destructive Stereotypes of Female Attorneys

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository University of New Hampshire – Franklin Pierce Law Faculty Scholarship School of Law 1-1-2005 Some Dumb Girl Syndrome: Challenging and Subverting Destructive Stereotypes of Female Attorneys Ann Bartow University of New Hampshire School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/law_facpub Part of the Gender and Sexuality Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Law and Gender Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Ann Bartow, "Some Dumb Girl Syndrome: Challenging and Subverting Destructive Stereotypes of Female Attorneys," 11 WM. & MARY J. WOMEN & L. 221 (2005). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of New Hampshire – Franklin Pierce School of Law at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOME DUMB GIRL SYNDROME: CHALLENGING AND SUBVERTING DESTRUCTIVE STEREOTYPES OF FEMALE ATTORNEYS ANN BARTOW* I. INTRODUCTION Almost every woman has had the experience of being trivialized, regarded as if she is just 'some dumb girl,' of whom few productive accomplishments can be expected. When viewed simply as 'some dumb girls,' women are treated dismissively, as if their thoughts or contributions are unlikely to be of value and are unworthy of consideration. 'Some Dumb Girl Syndrome' can arise in deeply personal spheres. A friend once described an instance of this phenomenon: When a hurricane threatened her coastal community, her husband, a military pilot, was ordered to fly his airplane to a base in the Midwest, far from the destructive reach of the impending storm. -

CELEBRATING SIGNIFICANT CHICAGO WOMEN Park &Gardens

Chicago Women’s Chicago Women’s CELEBRATING SIGNIFICANT CHICAGO WOMEN CHICAGO SIGNIFICANT CELEBRATING Park &Gardens Park Margaret T. Burroughs Lorraine Hansberry Bertha Honoré Palmer Pearl M. Hart Frances Glessner Lee Margaret Hie Ding Lin Viola Spolin Etta Moten Barnett Maria Mangual introduction Chicago Women’s Park & Gardens honors the many local women throughout history who have made important contributions to the city, nation, and the world. This booklet contains brief introductions to 65 great Chicago women—only a fraction of the many female Chicagoans who could be added to this list. In our selection, we strived for diversity in geography, chronology, accomplishments, and ethnicity. Only women with substantial ties to the City of Chicago were considered. Many other remarkable women who are still living or who lived just outside the City are not included here but are still equally noteworthy. We encourage you to visit Chicago Women’s Park FEATURED ABOVE and Gardens, where field house exhibitry and the Maria Goeppert Mayer Helping Hands Memorial to Jane Addams honor Katherine Dunham the important legacy of Chicago women. Frances Glessner Lee Gwendolyn Brooks Maria Tallchief Paschen The Chicago star signifies women who have been honored Addie Wyatt through the naming of a public space or building. contents LEADERS & ACTIVISTS 9 Dawn Clark Netsch 20 Viola Spolin 2 Grace Abbott 10 Bertha Honoré Palmer 21 Koko Taylor 2 Jane Addams 10 Lucy Ella Gonzales Parsons 21 Lois Weisberg 2 Helen Alvarado 11 Tobey Prinz TRAILBLAZERS 3 Joan Fujisawa Arai 11 Guadalupe Reyes & INNOVATORS 3 Ida B. Wells-Barnett 12 Maria del Jesus Saucedo 3 Willie T. -

The Heritage of Myra Bradwell's Chicago Legal News Richard H

digitalcommons.nyls.edu Faculty Scholarship Articles & Chapters 2003 A Brief History of Gender Law Journals: The Heritage of Myra Bradwell's Chicago Legal News Richard H. Chused New York Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/fac_articles_chapters Part of the Jurisprudence Commons, Law and Gender Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Columbia Journal of Gender and Law, Vol. 12, Issue 3 (2003), pp. 421-429 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles & Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@NYLS. A BRIEF HISTORY OF GENDER LAW JOURNALS: THE HERITAGE OF MYRA BRADWELL'S CHICAGO LEGAL NEWS RICHARD H CHUSED* In the front of the first issue of the Columbia Journal of Gender and Law published twelve years ago, the members of the staff inserted a brief statement of purpose.' Claiming that their "working job titles confer[red] no greater or lesser power, but serve[d] only to define primary responsibilities," they hoped "to publish legal and interdisciplinary writings on feminism and gender issues and to expand feminist jurisprudence., 2 For its moment in history, this was a fairly radical statement of purpose. Eschewing most aspects of hierarchy and viewing their primary audience as students and academics,3 the members aimed "to promote an expansive view of feminism embracing women and men of different colors, classes, sexual orientations, and cultures. ' 4 A brief comment by Ruth Bader Ginsburg followed immediately after the journal members' statement of purpose.5 She focused not on theoretical and philosophical questions, but on events preceding her rise to a position of power and authority. -

From False Paternalism to False Equality: Judicial Assaults on Feminist Community, Illinois 1869-1895

Michigan Law Review Volume 84 Issue 7 1986 From False Paternalism to False Equality: Judicial Assaults on Feminist Community, Illinois 1869-1895 Frances Olsen University of California at Los Angeles Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Law and Gender Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Frances Olsen, From False Paternalism to False Equality: Judicial Assaults on Feminist Community, Illinois 1869-1895, 84 MICH. L. REV. 1518 (1986). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol84/iss7/8 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FROM FALSE PATERNALISM TO FALSE EQUALITY: JUDICIAL ASSAULTS ON FEMINIST COMMUNITY, ILLINOIS 1869-1895 Frances Olsen* Feminist theorists seem to be obsessed by the question of whether women should emphasize their similarity to men or their differences from men. In discipline after discipline, the issue of sameness and dif ferences has come to center stage. This focus is not a new phenomenon. Early this century, suffrag ists fluctuated between claiming that it was important to let women vote because they were different from men - more sensitive to issues of world peace, the protection of children, and so forth - and claim ing that it was safe to let women vote because they would vote the same way men did. -

Myra Bradwell

The Pioneer Female Lawyer 1: Myra Bradwell by Karen L. Giffen We . who have seen the result of her work in the State of Illinois in shaping and helping carry through . reformatory measures . desire to express our appreciation. .To us,she is the pioneer woman lawyer.2 hese words were spoken in 1894 about This step, if taken by us, would mean that, things, indicates the domestic sphere as that Myra Bradwell, who some believe was in the opinion of this tribunal, every civil which properly belongs to the domain and TAmerica’s first female lawyer.3 office in this State may be filled by women; functions of womanhood. The harmony, not Although the acknowledgement may that it is in harmony with the spirit of our to say identity, of interest and views which seem trite, our license to practice law represents the constitution and laws that women should be belong, or should belong, to the family institu- privilege to speak to the powerful. Remarkably, made governors, judges and sheriffs. This we tion is repugnant to the idea of a woman Bradwell was among those women who demanded are not yet prepared to hold. adopting a distinct and independent career and won the right to speak to the powerful 30 years from that of her husband. .The paramount Bradwell responded to the court’s opinion as follows: before women’s suffrage. destiny and mission of woman are to fulfill What the decision of the Supreme Court of the noble and benign offices of wife and Bradwell began her legal career in 1868 when she the United States in the Dred Scott case was mother. -

Administration of Barack Obama, 2012 Digest of Other White House Announcements December 31, 2012 January 1 January 2 January

Administration of Barack Obama, 2012 Digest of Other White House Announcements December 31, 2012 The following list includes the President's public schedule and other items of general interest announced by the Office of the Press Secretary and not included elsewhere in this Compilation. January 1 In the morning, in Kailua, HI, the President had an intelligence briefing. January 2 In the morning, the President had an intelligence briefing. In the afternoon, the President, Mrs. Obama, and their daughters Sasha and Malia returned to Washington, DC, arriving the following morning. The White House announced that the President will travel to Cleveland, OH, on January 4. January 3 In the morning, in the Oval Office, the President and Vice President Joe Biden had an intelligence briefing. Then, also in the Oval Office, he met with his senior advisers. In the afternoon, in the Private Dining Room, the President and Vice President Biden had lunch. Later, in the Oval Office, they met with Secretary of Defense Leon E. Panetta. January 4 In the morning, in the Oval Office, the President and Vice President Joe Biden had an intelligence briefing. He then traveled to Cleveland, OH. In the afternoon, outside the home of William and Endia Eason, the President greeted Cleveland residents. Later, he returned to Washington, DC. The White House announced that the President will travel to the Pentagon in Arlington, VA, on January 5. The White House announced that the President will welcome the 2011 NBA champion Dallas Mavericks to the White House on January 9. The President announced the recess appointment of Richard A. -

Public Hearing Transcript, Chicago, IL (September 9-10, 2009)

1 1 UNITED STATES SENTENCING COMMISSION 2 PUBLIC HEARING 3 * * * * * * * * 4 WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 9, 2009 5 AND 6 THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 10, 2009 7 * * * * * * * * 8 The public hearing convened in the Hon. James Benton 9 Parsons Ceremonial Courtroom in the Everett McKinley Dirksen United States Courthouse, 219 South Dearborn Street, Chicago, 10 Illinois, at 8:45 a.m. Wednesday, September 9, 2009, and 9:05 a.m. Thursday, September 10, 2009, the Hon. Ricardo H. 11 Hinojosa, Acting Chair, presiding. 12 COMMISSIONERS PRESENT: 13 RICARDO H. HINOJOSA, Acting Chair WILLIAM B. CARR, JR., Vice Chair 14 RUBEN CASTILLO, Vice Chair WILLIAM K. SESSIONS, III, Vice Chair 15 DABNEY L. FRIEDRICH, Commissioner BERYL A. HOWELL, Commissioner 16 JONATHAN J. WROBLEWSKI, Ex-Officio Commissioner 17 STAFF PRESENT: 18 JUDITH W. SHEON, Staff Director BRENT NEWTON, Deputy Staff Director 19 20 21 Court Reporter: 22 KATHLEEN M. FENNELL, CSR, RPR, RMR, FCRR Official Court Reporter 23 United States District Court 219 South Dearborn Street, Suite 2144-A 24 Chicago, Illinois 60604 Telephone: (312) 435-5569 25 www.Kathyfennell.com 2 1 PANELISTS PRESENT: 2 HON. JAMES F. HOLDERMAN, JR., Chief District Judge, Northern District of Illinois 3 HON. JAMES G. CARR, Chief District Judge, Northern District 4 of Ohio 5 HON. GERALD E. ROSEN, Chief District Judge, Eastern District of Michigan 6 HON. JON P. McCALLA, Chief District Judge, Western District of 7 Tennessee 8 HON. KAREN K. CALDWELL, District Judge, Eastern District of Kentucky 9 HON. PHILIP PETER SIMON, District Judge, Northern District of 10 Indiana 11 PHILIP MILLER, Chief Probation Officer, Eastern District of Michigan 12 RICHARD TRACY, Chief Probation Officer, Northern District of 13 Illinois 14 HON. -

Lucy Hargrett Draper Center and Archives for the Study of the Rights

Lucy Hargrett Draper Center and Archives for the Study of the Rights of Women in History and Law Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library Special Collections Libraries University of Georgia Index 1. Legal Treatises. Ca. 1575-2007 (29). Age of Enlightenment. An Awareness of Social Justice for Women. Women in History and Law. 2. American First Wave. 1849-1949 (35). American Pamphlets timeline with Susan B. Anthony’s letters: 1853-1918. American Pamphlets: 1849-1970. 3. American Pamphlets (44) American pamphlets time-line with Susan B. Anthony’s letters: 1853-1918. 4. American Pamphlets. 1849-1970 (47). 5. U.K. First Wave: 1871-1908 (18). 6. U.K. Pamphlets. 1852-1921 (15). 7. Letter, autographs, notes, etc. U.S. & U.K. 1807-1985 (116). 8. Individual Collections: 1873-1980 (165). Myra Bradwell - Susan B. Anthony Correspondence. The Emily Duval Collection - British Suffragette. Ablerta Martie Hill Collection - American Suffragist. N.O.W. Collection - West Point ‘8’. Photographs. Lucy Hargrett Draper Personal Papers (not yet received) 9. Postcards, Woman’s Suffrage, U.S. (235). 10. Postcards, Women’s Suffrage, U.K. (92). 11. Women’s Suffrage Advocacy Campaigns (300). Leaflets. Broadsides. Extracts Fliers, handbills, handouts, circulars, etc. Off-Prints. 12. Suffrage Iconography (115). Posters. Drawings. Cartoons. Original Art. 13. Suffrage Artifacts: U.S. & U.K. (81). 14. Photographs, U.S. & U.K. Women of Achievement (83). 15. Artifacts, Political Pins, Badges, Ribbons, Lapel Pins (460). First Wave: 1840-1960. Second Wave: Feminist Movement - 1960-1990s. Third Wave: Liberation Movement - 1990-to present. 16. Ephemera, Printed material, etc (114). 17. U.S. & U.K.