From False Paternalism to False Equality: Judicial Assaults on Feminist Community, Illinois 1869-1895

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Circuit Circuit

November 2013 Featured In This Issue The Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals Gets A New Chief Judge, by Brian J. Paul The Changing of the Guard in the Northern District of Illinois, by Jeffrey Cole Address to the Seventh Circuit Bar Association and the Seventh Circuit Judicial Conference Annual Joint TheThe Meeting May 6, 2013, by Senator Richard G. Lugar Through the Eyes of a Juror: A Lawyer's Perspective from Inside the Jury Room, by Karen McNulty Enright The Seventh Circuit Inters "Self-Serving" as an Objection to the Admissibility of Evidence, by Jeffrey Cole My Defining Experience as a Lawyer: Taking a Seventh Circuit Appeal, by Ravi Shankar CirCircuitcuit How 30 Women Changed the Course of the Nation’s Legal and Social History: Commemorating the First National Meeting of Women Lawyers in America, by Gwen Jordan J.D., Ph.D. Common Pleading Deficiencies in RICO Claims, by Andrew C. Erskine You Can Have It Both Ways: Fourth Amendment Standing in the Seventh Circuit, by Christopher Ferro and Marc Kadish RiderRiderT HE J OURNALOFTHE S EVENTH A Life Well Lived, by Steven Lubet C IRCUITIRCUIT B AR A SSOCIATION Significant Amendments to Rule 45, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, to Take Effect on December 1, 2013, by Jeffrey Cole Sealing Portions of the Appellate Record: A Guide for Seventh Circuit Practitioners, by Alexandra L. Newman Changes &Challenges The Circuit Rider In This Issue Letter from the President . .1 The Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals Gets A New Chief Judge, by Brian J. Paul . 2-4 The Changing of the Guard in the Northern District of Illinois, by Jeffrey Cole . -

Self-Reflection Within the Academy: the Absence of Women in Constitutional Jurisprudence Karin Mika

Hastings Women’s Law Journal Volume 9 | Number 2 Article 6 7-1-1998 Self-Reflection within the Academy: The Absence of Women in Constitutional Jurisprudence Karin Mika Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hwlj Recommended Citation Karin Mika, Self-Reflection within the Academy: The Absence of Women in Constitutional Jurisprudence, 9 Hastings Women's L.J. 273 (1998). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hwlj/vol9/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Women’s Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. & Self-Reflection within the Academy: The Absence of Women in Constitutional Jurisprudence Karin Mika* One does not have to be an ardent feminist to recognize that the con tributions of women in our society have been largely unacknowledged by both history and education. l Individuals need only be reasonably attentive to recognize there is a similar absence of women within the curriculum presented in a standard legal education. If one reads Elise Boulding's The Underside of History2 it is readily apparent that there are historical links between the achievements of women and Nineteenth century labor reform, Abolitionism, the Suffrage Movement and the contemporary view as to what should be protected First Amendment speech? Despite Boulding's depiction, treatises and texts on both American Legal History-and those tracing the development of Constitutional Law-present these topics as distinct and without any significant intersection.4 The contributions of women within all of these movements, except perhaps for the rarely men- *Assistant Director, Legal Writing Research and Advocacy Cleveland-Marshall College of Law. -

Social Workers and the Development of the NAACP Linda S

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarWorks at WMU The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare Volume 21 Article 11 Issue 1 March March 1994 Social Workers and the Development of the NAACP Linda S. Moore Texas Christian University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jssw Part of the African American Studies Commons, and the Social Work Commons Recommended Citation Moore, Linda S. (1994) "Social Workers and the Development of the NAACP," The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare: Vol. 21 : Iss. 1 , Article 11. Available at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jssw/vol21/iss1/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Social Work at ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Social Workers and the Development of the NAACP LINDA S. MOORE Texas Christian University Social Work Program This article addresses the relationship between African-American leaders and settlement house workers in the development of the NAACP. Using social movement theory and Hasenfeld and Tropman's conceptualframe- work for interorganizationalrelations, it analyzes the linkages developed between voluntary associationsand how they benefitted all involved. This linkage provides lessons for today's struggle for social justice. Introduction This paper discusses the origins of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) including the role played by settlement house workers in the development and ongoing leadership of that organization. Using social move- ment theory and Hasenfeld and Tropman's (1977) conceptual framework for interorganizational relations, it analyzes the way voluntary associations come together to create and maintain linkages which benefit all parties. -

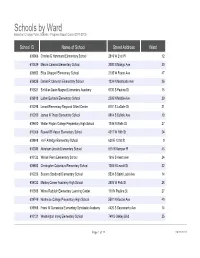

Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012)

Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012) School ID Name of School Street Address Ward 609966 Charles G Hammond Elementary School 2819 W 21st Pl 12 610539 Marvin Camras Elementary School 3000 N Mango Ave 30 609852 Eliza Chappell Elementary School 2135 W Foster Ave 47 609835 Daniel R Cameron Elementary School 1234 N Monticello Ave 26 610521 Sir Miles Davis Magnet Elementary Academy 6730 S Paulina St 15 609818 Luther Burbank Elementary School 2035 N Mobile Ave 29 610298 Lenart Elementary Regional Gifted Center 8101 S LaSalle St 21 610200 James N Thorp Elementary School 8914 S Buffalo Ave 10 609680 Walter Payton College Preparatory High School 1034 N Wells St 27 610056 Roswell B Mason Elementary School 4217 W 18th St 24 609848 Ira F Aldridge Elementary School 630 E 131st St 9 610038 Abraham Lincoln Elementary School 615 W Kemper Pl 43 610123 William Penn Elementary School 1616 S Avers Ave 24 609863 Christopher Columbus Elementary School 1003 N Leavitt St 32 610226 Socorro Sandoval Elementary School 5534 S Saint Louis Ave 14 609722 Manley Career Academy High School 2935 W Polk St 28 610308 Wilma Rudolph Elementary Learning Center 110 N Paulina St 27 609749 Northside College Preparatory High School 5501 N Kedzie Ave 40 609958 Frank W Gunsaulus Elementary Scholastic Academy 4420 S Sacramento Ave 14 610121 Washington Irving Elementary School 749 S Oakley Blvd 25 Page 1 of 28 09/23/2021 Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012) 610352 Durkin Park Elementary School -

The 19Th Amendment

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Women Making History: The 19th Amendment Women The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation. —19th Amendment to the United States Constitution In 1920, after decades of tireless activism by countless determined suffragists, American women were finally guaranteed the right to vote. The year 2020 marks the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. It was ratified by the states on August 18, 1920 and certified as an amendment to the US Constitution on August 26, 1920. Developed in partnership with the National Park Service, this publication weaves together multiple stories about the quest for women’s suffrage across the country, including those who opposed it, the role of allies and other civil rights movements, who was left behind, and how the battle differed in communities across the United States. Explore the complex history and pivotal moments that led to ratification of the 19th Amendment as well as the places where that history happened and its continued impact today. 0-31857-0 Cover Barcode-Arial.pdf 1 2/17/20 1:58 PM $14.95 ISBN 978-1-68184-267-7 51495 9 781681 842677 The National Park Service is a bureau within the Department Front cover: League of Women Voters poster, 1920. of the Interior. It preserves unimpaired the natural and Back cover: Mary B. Talbert, ca. 1901. cultural resources and values of the National Park System for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this work future generations. -

A HISTORICAL COMPARISON of FEMALE POLITICAL INVOLVEMENT in EARLY NATIVE AMERICA and the US O

42838-elo_13 Sheet No. 169 Side B 12/23/2020 10:41:31 SULLIVAN_FINAL (APPROVED).DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 12/21/20 6:54 PM THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING A WOMAN:AHISTORICAL COMPARISON OF FEMALE POLITICAL INVOLVEMENT IN EARLY NATIVE AMERICA AND THE U.S. SPENSER M. SULLIVAN∗ “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”1 I. INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................................................................335 II. REPUBLICAN MOTHERHOOD AND THE “SEPARATE SPHERES” DOCTRINE............................................................................................................................................338 A. Women in the Pre-Revolutionary Era ..............................338 B. The Role of Women in the U.S. Constitution.................339 C. Enlightenment Influences................................................340 D. Republican Mothers.........................................................341 III. WOMEN’S CITIZENSHIP AND THE BARRIERS TO LEGAL EQUALITY....343 A. Defining Female Citizenship in the Founding Era .........343 B. Women’s Ownership of Property–the Feme Covert Conundrum....................................................................344 C. Martin v. Commonwealth: The Rights of the Feme Covert .............................................................................346 D. Bradwell v. Illinois: The Privileges and Immunities of 42838-elo_13 Sheet No. 169 Side B 12/23/2020 -

Anne Henrietta Martin Papers BANC MSS P-G 282

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf1t1n993s No online items Anne Henrietta Martin Papers BANC MSS P-G 282 Processed by The Bancroft Library staff The Bancroft Library The Bancroft Library University of California Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 (510) 642-6481 [email protected] Anne Henrietta Martin Papers BANC MSS P-G 282 1 BANC MSS P-G 282 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: The Bancroft Library Title: Anne Henrietta Martin Papers creator: Martin, Anne, 1875-1951 Identifier/Call Number: BANC MSS P-G 282 Physical Description: Linear feet: 25Boxes: 19; Cartons: 10; Volumes: 12 Date (inclusive): 1834-1951 Date (bulk): 1900-1951 Abstract: Papers pertaining to Martin's activities for woman suffrage, feminism, social hygiene, and pacificism. Also included are materials relating to her U.S. Senate campaigns in Nevada in 1918 and 1920. Correspondents include: Dean Acheson, Jane Addams, Gertrude Atherton, Mary Austin, Mary Ritter Beard, Carrie Chapman Catt, Katherine Fisher, Henry Ford, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Herbert Hoover, Cordell Hull, Belle La Follette, Henry Cabot Lodge, Margaret Long, H.L. Mencken, Francis G. Newlands, Alice Paul, Key Pittman, Jenette Rankin, Theodore Roosevelt, Upton Sinclair, Margaret Chase Smith, Lincoln Steffens, Dorothy Thompson, Mabel Vernon, Charles Erskine, Scott Wood, Margaret Wood, and Maud Younger. The correspondence is supplemented by a large bulk of manuscripts and notes, pamphlets, magazine and newspaper clippings, campaign miscellany, suffrage material, personalia, and scrapbooks. Language of Material: English For current information on the location of these materials, please consult the Library's online catalog. Publication Rights Materials in this collection may be protected by the U.S. -

How the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Began, 1914 Reissued 1954

How the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Began By MARY WHITE OVINGTON NATIONAL AssociATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT oF CoLORED PEOPLE 20 WEST 40th STREET, NEW YORK 18, N. Y. MARY DUNLOP MACLEAN MEMORIAL FUND First Printing 1914 HOW THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE BEGAN By MARY WHITE OVINGTON (As Originally printed in 1914) HE National Association for the studying the status of the Negro in T Advancement of Colored People New York. I had investigated his hous is five years old-old enough, it is be ing conditions, his health, his oppor lieved, to have a history; and I, who tunities for work. I had spent many am perhaps its first member, have months in the South, and at the time been chosen as the person to recite it. of Mr. Walling's article, I was living As its work since 1910 has been set in a New York Negro tenement on a forth in its annual reports, I shall Negro street. And my investigations and make it my task to show how it came my surroundings led me to believe with into existence and to tell of its first the writer of the article that "the spirit months of work. of the abolitionists must be revived." In the summer of 1908, the country So I wrote to Mr. Walling, and after was shocked by the account of the race some time, for he was in the West, we riots at Springfield, Illinois. Here, in met in New York in-the first week of the home of Abraham Lincoln, a mob the year 1909. -

SAINT JANE and The

"f/Vhen Jane Addams opc11ed Hull- House .for Chicago's im1m:~rants, she began asking q1testions a local politician preferred not to answer SAINT JANE and the By ANNE FIROR SCOTT Powers: the boss, and not eager to quit. f Alderman .John Powers of Chicago's teeming had some hand in nearly every corrupt ordinance nineLee11Lh ward had been prescient, he might passed by the council during his years in oflice. ln a have foreseen Lrouble when two young ladies not single year, 1 895, he was Lo help to sell six important I long out of the female semin;1ry in Rockford, ciLy franchises. \\7hen the mayor vetoed Powers' meas Illinois, moved into a dilapidated old house on Hal ures, a silent but sign i fica 11 t two-thirds vote appeared sLed StreeL in Sep tern ber, 1889, and announced Lhem to override the veto. selves "al home" LO Lite neighbors. The ladies, however, Ray Stannard Baker, who chanced to observe Powers were nol very noisy about it, and it is doubtful if in the late nineties, recorded that he was shrewd and Powers was aware of their existence. The nineteenth silent, letting other men make the speeches and bring ward was well supplied with people already- grm1·ing upon their heads the abuse of the public. Powers was numbers of Italians, Poles, Russians, lrish, and oLher a short, swcky man, Baker said, "\\'ith a flaring gray immigrants- and two more would hardly be noticed. pompadour, a smooth-shaven face [sic], rather heavy Johnny Powers was the prototype of the ward boss features, and a resLless eye." One observer remarked who was coming to be an increasingly decisive figure that "the shadow of sympathetic gloom is always about on the American political scene. -

Some Dumb Girl Syndrome: Challenging and Subverting Destructive Stereotypes of Female Attorneys

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository University of New Hampshire – Franklin Pierce Law Faculty Scholarship School of Law 1-1-2005 Some Dumb Girl Syndrome: Challenging and Subverting Destructive Stereotypes of Female Attorneys Ann Bartow University of New Hampshire School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/law_facpub Part of the Gender and Sexuality Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Law and Gender Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Ann Bartow, "Some Dumb Girl Syndrome: Challenging and Subverting Destructive Stereotypes of Female Attorneys," 11 WM. & MARY J. WOMEN & L. 221 (2005). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of New Hampshire – Franklin Pierce School of Law at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOME DUMB GIRL SYNDROME: CHALLENGING AND SUBVERTING DESTRUCTIVE STEREOTYPES OF FEMALE ATTORNEYS ANN BARTOW* I. INTRODUCTION Almost every woman has had the experience of being trivialized, regarded as if she is just 'some dumb girl,' of whom few productive accomplishments can be expected. When viewed simply as 'some dumb girls,' women are treated dismissively, as if their thoughts or contributions are unlikely to be of value and are unworthy of consideration. 'Some Dumb Girl Syndrome' can arise in deeply personal spheres. A friend once described an instance of this phenomenon: When a hurricane threatened her coastal community, her husband, a military pilot, was ordered to fly his airplane to a base in the Midwest, far from the destructive reach of the impending storm. -

CELEBRATING SIGNIFICANT CHICAGO WOMEN Park &Gardens

Chicago Women’s Chicago Women’s CELEBRATING SIGNIFICANT CHICAGO WOMEN CHICAGO SIGNIFICANT CELEBRATING Park &Gardens Park Margaret T. Burroughs Lorraine Hansberry Bertha Honoré Palmer Pearl M. Hart Frances Glessner Lee Margaret Hie Ding Lin Viola Spolin Etta Moten Barnett Maria Mangual introduction Chicago Women’s Park & Gardens honors the many local women throughout history who have made important contributions to the city, nation, and the world. This booklet contains brief introductions to 65 great Chicago women—only a fraction of the many female Chicagoans who could be added to this list. In our selection, we strived for diversity in geography, chronology, accomplishments, and ethnicity. Only women with substantial ties to the City of Chicago were considered. Many other remarkable women who are still living or who lived just outside the City are not included here but are still equally noteworthy. We encourage you to visit Chicago Women’s Park FEATURED ABOVE and Gardens, where field house exhibitry and the Maria Goeppert Mayer Helping Hands Memorial to Jane Addams honor Katherine Dunham the important legacy of Chicago women. Frances Glessner Lee Gwendolyn Brooks Maria Tallchief Paschen The Chicago star signifies women who have been honored Addie Wyatt through the naming of a public space or building. contents LEADERS & ACTIVISTS 9 Dawn Clark Netsch 20 Viola Spolin 2 Grace Abbott 10 Bertha Honoré Palmer 21 Koko Taylor 2 Jane Addams 10 Lucy Ella Gonzales Parsons 21 Lois Weisberg 2 Helen Alvarado 11 Tobey Prinz TRAILBLAZERS 3 Joan Fujisawa Arai 11 Guadalupe Reyes & INNOVATORS 3 Ida B. Wells-Barnett 12 Maria del Jesus Saucedo 3 Willie T. -

The Heritage of Myra Bradwell's Chicago Legal News Richard H

digitalcommons.nyls.edu Faculty Scholarship Articles & Chapters 2003 A Brief History of Gender Law Journals: The Heritage of Myra Bradwell's Chicago Legal News Richard H. Chused New York Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/fac_articles_chapters Part of the Jurisprudence Commons, Law and Gender Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Columbia Journal of Gender and Law, Vol. 12, Issue 3 (2003), pp. 421-429 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles & Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@NYLS. A BRIEF HISTORY OF GENDER LAW JOURNALS: THE HERITAGE OF MYRA BRADWELL'S CHICAGO LEGAL NEWS RICHARD H CHUSED* In the front of the first issue of the Columbia Journal of Gender and Law published twelve years ago, the members of the staff inserted a brief statement of purpose.' Claiming that their "working job titles confer[red] no greater or lesser power, but serve[d] only to define primary responsibilities," they hoped "to publish legal and interdisciplinary writings on feminism and gender issues and to expand feminist jurisprudence., 2 For its moment in history, this was a fairly radical statement of purpose. Eschewing most aspects of hierarchy and viewing their primary audience as students and academics,3 the members aimed "to promote an expansive view of feminism embracing women and men of different colors, classes, sexual orientations, and cultures. ' 4 A brief comment by Ruth Bader Ginsburg followed immediately after the journal members' statement of purpose.5 She focused not on theoretical and philosophical questions, but on events preceding her rise to a position of power and authority.