Map. Timor-Leste in Southeast Asia. Map Created by “Hariboneagle927,” Adapted by the Authors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Trajectories of the Early-Modern Kingdoms in Eastern Indonesia: Comparative Perspectives

Trajectories of the early-modern kingdoms in eastern Indonesia: Comparative perspectives Hans Hägerdal Introduction The king grew increasingly powerful. His courage indeed resembled that of a lion. He wisely attracted the hearts of the people. The king was a brave man who was sakti and superior in warfare. In fact King Waturenggong was like the god Vishnu, at times having four arms. The arms held the cakra, the club, si Nandaka, and si Pañcajania. How should this be understood? The keris Ki Lobar and Titinggi were like the club and cakra of the king. Ki Tandalanglang and Ki Bangawan Canggu were like Sangka Pañcajania and the keris si Nandaka; all were the weapons of the god Vishnu which were very successful in defeating ferocious enemies. The permanent force of the king was called Dulang Mangap and were 1,600 strong. Like Kalantaka it was led by Kriyan Patih Ularan who was like Kalamretiu. It was dispatched to crush Dalem Juru [king of Blambangan] since Dalem Juru did not agree to pass over his daughter Ni Bas […] All the lands submitted, no-one was the equal to the king in terms of bravery. They were all ruled by him: Nusa Penida, Sasak, Sumbawa, and especially Bali. Blambangan until Puger had also been subjugated, all was lorded by him. Only Pasuruan and Mataram were not yet [subjugated]. These lands were the enemies (Warna 1986: 78, 84). Thus did a Balinese chronicler recall the deeds of a sixteenth-century ruler who supposedly built up a mini-empire that stretched from East Java to Sumbawa. -

8Th Euroseas Conference Vienna, 11–14 August 2015

book of abstracts 8th EuroSEAS Conference Vienna, 11–14 August 2015 http://www.euroseas2015.org contents keynotes 3 round tables 4 film programme 5 panels I. Southeast Asian Studies Past and Present 9 II. Early And (Post)Colonial Histories 11 III. (Trans)Regional Politics 27 IV. Democratization, Local Politics and Ethnicity 38 V. Mobilities, Migration and Translocal Networking 51 VI. (New) Media and Modernities 65 VII. Gender, Youth and the Body 76 VIII. Societal Challenges, Inequality and Conflicts 87 IX. Urban, Rural and Border Dynamics 102 X. Religions in Focus 123 XI. Art, Literature and Music 138 XII. Cultural Heritage and Museum Representations 149 XIII. Natural Resources, the Environment and Costumary Governance 167 XIV. Mixed Panels 189 euroseas 2015 . book of abstracts 3 keynotes Alarms of an Old Alarmist Benedict Anderson Have students of SE Asia become too timid? For example, do young researchers avoid studying the power of the Catholic Hierarchy in the Philippines, the military in Indonesia, and in Bangkok monarchy? Do sociologists and anthropologists fail to write studies of the rising ‘middle classes’ out of boredom or disgust? Who is eager to research the very dangerous drug mafias all over the place? How many track the spread of Western European, Russian, and American arms of all types into SE Asia and the consequences thereof? On the other side, is timidity a part of the decay of European and American universities? Bureaucratic intervention to bind students to work on what their state think is central (Terrorism/Islam)? -

4. Old Track, Old Path

4 Old track, old path ‘His sacred house and the place where he lived,’ wrote Armando Pinto Correa, an administrator of Portuguese Timor, when he visited Suai and met its ruler, ‘had the name Behali to indicate the origin of his family who were the royal house of Uai Hali [Wehali] in Dutch Timor’ (Correa 1934: 45). Through writing and display, the ruler of Suai remembered, declared and celebrated Wehali1 as his origin. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the Portuguese increased taxes on the Timorese, which triggered violent conflict with local rulers, including those of Suai. The conflict forced many people from Suai to seek asylum across the border in West Timor. At the end of 1911, it was recorded that more than 2,000 East Timorese, including women and children, were granted asylum by the Dutch authorities and directed to settle around the southern coastal plain of West Timor, in the land of Wehali (La Lau 1912; Ormelling 1957: 184; Francillon 1967: 53). On their arrival in Wehali, displaced people from the village of Suai (and Camenaça) took the action of their ruler further by naming their new settlement in West Timor Suai to remember their place of origin. Suai was once a quiet hamlet in the village of Kletek on the southern coast of West Timor. In 1999, hamlet residents hosted their brothers and sisters from the village of Suai Loro in East Timor, and many have stayed. With a growing population, the hamlet has now become a village with its own chief asserting Suai Loro origin; his descendants were displaced in 1911. -

The Portuguese Colonization and the Problem of East Timorese Nationalism

Ivo Carneiro de SOUSA, Lusotopie 2001 : 183-194 The Portuguese Colonization and the Problem of East Timorese Nationalism hen we speak about East Timor, what precisely are we talking about ? Half an island located on the easternmost tip of the Archipelago of the Lesser Sunda Islands, near Australia and New W 2 Guinea, 19 000 km in area, a fifth of the size of Portugal, with approximately 800,000 inhabitants. The territory’s process of decolonization was brutally interrupted in 1975 by a prolonged and violent colonial occupation by Indonesia, which was definitively rejected and dissolved by the referendum of August 1999. It was then followed by brutal violence, terminating with the intervention of the United Nations, which came to administer the transition process to independence, still undeclared but increasingly a reality with the recent elections for the Constituent Assembly, clearly won by Fretilin. Unquestionably, East Timor has became an important issue in political discourse, particularly in Portugal. All expressions of solidarity, with their groups and influences, each with their own motivations and causes, have revealed a growing interest in the East Timorese problem. Consequently, the territory became the object of concern for international politics and solidarities. However, research in social sciences has been lacking. Scientific studies in the fields of history, sociology, anthropology or economics are extremely rare, something which can be largely explained by the difficulty in obtaining free access to the territory of East Timor during the period of the Indonesian occupation, a situation which has yet to be overcome because of the enormous difficulties in organising the reconstruction of a devastated and disorganised territory, confronted with international aid which transports economies, inflation and even social behaviours practically unknown to the local populations. -

The Making of Middle Indonesia Verhandelingen Van Het Koninklijk Instituut Voor Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde

The Making of Middle Indonesia Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde Edited by Rosemarijn Hoefte KITLV, Leiden Henk Schulte Nordholt KITLV, Leiden Editorial Board Michael Laffan Princeton University Adrian Vickers Sydney University Anna Tsing University of California Santa Cruz VOLUME 293 Power and Place in Southeast Asia Edited by Gerry van Klinken (KITLV) Edward Aspinall (Australian National University) VOLUME 5 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/vki The Making of Middle Indonesia Middle Classes in Kupang Town, 1930s–1980s By Gerry van Klinken LEIDEN • BOSTON 2014 This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution‐ Noncommercial 3.0 Unported (CC‐BY‐NC 3.0) License, which permits any non‐commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. The realization of this publication was made possible by the support of KITLV (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies). Cover illustration: PKI provincial Deputy Secretary Samuel Piry in Waingapu, about 1964 (photo courtesy Mr. Ratu Piry, Waingapu). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Klinken, Geert Arend van. The Making of middle Indonesia : middle classes in Kupang town, 1930s-1980s / by Gerry van Klinken. pages cm. -- (Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, ISSN 1572-1892; volume 293) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-26508-0 (hardback : acid-free paper) -- ISBN 978-90-04-26542-4 (e-book) 1. Middle class--Indonesia--Kupang (Nusa Tenggara Timur) 2. City and town life--Indonesia--Kupang (Nusa Tenggara Timur) 3. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

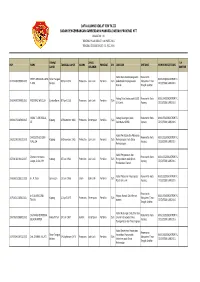

Data Alumni Diklat Pim Tk.Iii Badan Pengembangan Sumberdaya

DATA ALUMNI DIKLAT PIM TK.III BADAN PENGEMBANGAN SUMBERDAYA MANUSIA DAERAH PROVINSI NTT ANGKATAN : 09 TANGGAL MULAI DIKLAT : 14 MARE 2016 TANGGAL SELESAI DIKLAT: 01 JULI 2016 TEMPAT JENIS TLP NIP NAMA TANGGAL LAHIR AGAMA PANGKAT GOL JABATAN INSTANSI NOMOR REGISTRASI LAHIR KELAMIN KANTOR Kabid Data dan Kepangkatan Pemerintah AFRET APRIANUS LOPO, Timor Tengah 00001548/DIKLATPIM TK. 197204091999031009 09 April 1972 Protestan Laki-Laki Pembina IV/a pada Badan Kepegawaian Kabupaten Timor S.SOS Selatan III/53/5300/LAN/2016 Daerah Tengah Selatan Kabag Tata Usaha pada RSUD Pemerintah Kota 00001549/DIKLATPIM TK. 196504071999031002 ANDERIAS WOLI,SH Sumba Barat 07 April 2016 Protestan Laki-Laki Pembina IV/a S.K.Lerik Kupang III/53/5300/LAN/2016 ANIKA T.LENI BELLA, Kabag Keuangan pada Pemerintah Kota 00001550/DIKLATPIM TK. 196811251995032005 Kupang 25 November 1968 Protestan Perempuan Pembina IV/a SE Sekretariat DPRD Kupang III/53/5300/LAN/2016 Kabid Penataan dan Pelayanan DAVIDZON EDISON Pemerintah Kota 00001551/DIKLATPIM TK. 196312081985121005 Kupang 08 Desember 1962 Protestan Laki-Laki Pembina IV/a Perhubungan Pada Dinas PUAS,SH Kupang III/53/5300/LAN/2016 Perhubungan Kabid Pengawasan dan Djarmes Herminus Pemerintah Kota 00001552/DIKLATPIM TK. 197001022001121007 Kupang 05 Juni 1968 Protestan Laki-Laki Pembina IV/a Pengendalian pada Dinas Lango, S.Sos,.MM Kupang III/53/5300/LAN/2016 Pendapatan Daerah Kabid Pelayanan Medis pada Pemerintah Kota 00001553/DIKLATPIM TK. 196806152002121005 dr. M.Ihsan Lamongan 15 Juni 1968 Islam Laki-Laki Pembina IV/a RSUD SK Lerik Kupang III/53/5300/LAN/2016 Pemerintah dr.R.A.KAROLINA Kepala Rumah Sakit Umum 00001554/DIKLATPIM TK. -

Customary Law Toward Matamusan Determination

CUSTOMARY LAW TOWARD MATAMUSAN DETERMINATION TO CUSTOM SOCIETY AT WEWIKU WEHALI, BELU, NTT Roswita Nelviana Bria (Corresponing Author) Departement of Language and Letters, Kanjuruhan University of Malang Jl. S Supriyadi 48 Malang, East Java, Indonesia Phone: (+62) 813 365 182 51 E-mail: [email protected] Sujito Departement of Language and Letters, Kanjuruhan University of Malang Jl. S Supriyadi 48 Malang, East Java, Indonesia Phone: (+62) 817 965 77 89 E-mail: [email protected] Maria G.Sriningsih English Literature Facultyof Languageand Literature Kanjuruhan University of Malang Jl. S. Supriyadi No. 48 Malang 65148, East Java, Indonesia Phone: (+62) 85 933 033 177 E-mail: ABSTRACT Customary law is the law or unwritten rule that grow and thrive in a society that is only obeyed bycostom society in Belu. One of the most important customary law in Belu is the marriage law. Matrilineality system in 94 south Belunese descent is traced through the mother and maternal ancestors.However, in this matrilineal system, there is still a customary law that maintains the father‘s lineage based on customary law by adopting which called matamusanwhich is really ineresting because it is dfferent with matrilineal system in Minangkabau as the most popular matrilineal society. The research design of this thesis is descriptive qualitative research. It is intended to describe about matamusan as customary adoption system, chronological step of matamusan determination, the development of matamusan implementation, factors influencing the development of matamusan determination, and the effectiveness of customarylaw toward matamusandetermination.From the result of this study, it was clear that customary law is still effective in handle the violation of matamusan determination. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/25/2021 08:57:46PM Via Free Access | Lords of the Land, Lords of the Sea

3 Traditional forms of power tantalizing shreds of evidence It has so far been shown how external forces influenced the course of events on Timor until circa 1640, and how Timor can be situated in a regional and even global context. Before proceeding with an analysis of how Europeans established direct power in the 1640s and 1650s, it will be necessary to take a closer look at the type of society that was found on the island. What were the ‘traditional’ political hierarchies like? How was power executed before the onset of a direct European influence? In spite of all the travel accounts and colonial and mission- ary reports, the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century source material for this region is not rich in ethnographic detail. The aim of the writers was to discuss matters related to the execution of colonial policy and trade, not to provide information about local culture. Occasionally, there are fragments about how the indigenous society functioned, but in order to progress we have to compare these shreds of evidence with later source material. Academically grounded ethnographies only developed in the nineteenth century, but we do possess a certain body of writing from the last 200 years carried out by Western and, later, indigenous observers. Nevertheless, such a comparison must be applied with cau- tion. Society during the last two centuries was not identical to that of the early colonial period, and may have been substantially different in a number of respects. Although Timorese society was low-technology and apparently slow-changing until recently, the changing power rela- tions, the dissemination of firearms, the introduction of new crops, and so on, all had an impact – whether direct or indirect – on the struc- ture of society. -

Guidelines on Dealing with Collections from Colonial Contexts

Guidelines on Dealing with Collections from Colonial Contexts Guidelines on Dealing with Collections from Colonial Contexts Imprint Guidelines on Dealing with Collections from Colonial Contexts Publisher: German Museums Association Contributing editors and authors: Working Group on behalf of the Board of the German Museums Association: Wiebke Ahrndt (Chair), Hans-Jörg Czech, Jonathan Fine, Larissa Förster, Michael Geißdorf, Matthias Glaubrecht, Katarina Horst, Melanie Kölling, Silke Reuther, Anja Schaluschke, Carola Thielecke, Hilke Thode-Arora, Anne Wesche, Jürgen Zimmerer External authors: Veit Didczuneit, Christoph Grunenberg Cover page: Two ancestor figures, Admiralty Islands, Papua New Guinea, about 1900, © Übersee-Museum Bremen, photo: Volker Beinhorn Editing (German Edition): Sabine Lang Editing (English Edition*): TechniText Translations Translation: Translation service of the German Federal Foreign Office Design: blum design und kommunikation GmbH, Hamburg Printing: primeline print berlin GmbH, Berlin Funded by * parts edited: Foreword, Chapter 1, Chapter 2, Chapter 3, Background Information 4.4, Recommendations 5.2. Category 1 Returning museum objects © German Museums Association, Berlin, July 2018 ISBN 978-3-9819866-0-0 Content 4 Foreword – A preliminary contribution to an essential discussion 6 1. Introduction – An interdisciplinary guide to active engagement with collections from colonial contexts 9 2. Addressees and terminology 9 2.1 For whom are these guidelines intended? 9 2.2 What are historically and culturally sensitive objects? 11 2.3 What is the temporal and geographic scope of these guidelines? 11 2.4 What is meant by “colonial contexts”? 16 3. Categories of colonial contexts 16 Category 1: Objects from formal colonial rule contexts 18 Category 2: Objects from colonial contexts outside formal colonial rule 21 Category 3: Objects that reflect colonialism 23 3.1 Conclusion 23 3.2 Prioritisation when examining collections 24 4. -

Pahlawan-Pahlawan Suku Timor

TIDAK DIPERJUALBELIKAN Proyek Bahan Pustaka Lokal Konten Berbasis Etnis Nusantara Perpustakaan Nasional, 2011 PAHLAWAN-PAHLAWAN SUKU TIMOR oleh I.H. DOKO Perpustakaan Nasional Balai Pustaka R e p u b l i k I n d o n e s i a Penerbit dan Percetakan PN BALAI PUSTAKA BPNo. 2847 Hak pengarang dilindungi Undang-undang Cetakan pertama 1981 Gambar kulit: B.L. Bambang Prasodjo. KATAPENGANTAR Bahwa perjuangan menentang kaum penjajah di Timor sudah ada sejak bangsa asing berusaha berkuasa di bagian Tanah Air kita ini, mungkin belum banyak yang mengetahuinya. Bacaan yang memperkenalkan para pahlawan bangsa kita yang ada di wilayah ini dapat dikatakan tidak ada. Kalau pun ada mungkin hanya terbatas di Pulau Timor dan sekitarnya saja. Kami sajikan pada kesempatan ini episode-episode perjuangan para pahlawan kita di Timor dan dilengkapi pula dengan ilustrasi-ilustrasi historis. Kami yakin bacaan ini akan sangat besar artinya bagi para remaja dan masyarakat umumnya di seluruh Tanah Air kita. Taktik serta strategi perjuangan dapat berbeda-beda, tetapi yang jelas sama ialah: Setiap suku bangsa kita sejak dulu menolak segala bentuk penjajahan oleh siapa pun. PN Balai Pustaka PENDAHULUAN Ahli sejarah J. Toynbcc menyatakan bahwa dengan mempelajari jalan sejarah, kita akan lebih memahami keadaan kita sekarang dan masalah kita yang akan datang. Memang tepat sekali ucapan itu, karena tidak ada hari esok tanpa melalui hari ini dan demikian pula tidak ada hari ini tanpa melewati hari kemarin. Di dorong oleh keyakinan inilah, maka buku mengenai "Para Pahlawan Suku Timor" ini disusun sebagai bahan bacaan untuk masyarakat umum, khususnya untuk para siswa dan pemuda bangsa kita di daerah Nusa Tenggara Timur, yang pasti ingin lebih banyak mengetahui tentang kisah kehidupan dan perjuangan tokoh-tokoh di daerahnya, sebagai bagian mutlak dari perjuangan Bangsa Indonesia dalam mencapai Kemerdekaan Tanah Air dan Bangsa. -

Inventory of the Oriental Manuscripts of the Library of the University of Leiden

INVENTORIES OF COLLECTIONS OF ORIENTAL MANUSCRIPTS INVENTORY OF THE ORIENTAL MANUSCRIPTS OF THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF LEIDEN VOLUME 7 MANUSCRIPTS OR. 6001 – OR. 7000 REGISTERED IN LEIDEN UNIVERSITY LIBRARY IN THE PERIOD BETWEEN MAY 1917 AND 1946 COMPILED BY JAN JUST WITKAM PROFESSOR OF PALEOGRAPHY AND CODICOLOGY OF THE ISLAMIC WORLD IN LEIDEN UNIVERSITY INTERPRES LEGATI WARNERIANI TER LUGT PRESS LEIDEN 2007 © Copyright by Jan Just Witkam & Ter Lugt Press, Leiden, The Netherlands, 2006, 2007. The form and contents of the present inventory are protected by Dutch and international copyright law and database legislation. All use other than within the framework of the law is forbidden and liable to prosecution. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the author and the publisher. First electronic publication: 17 September 2006. Latest update: 30 July 2007 Copyright by Jan Just Witkam & Ter Lugt Press, Leiden, The Netherlands, 2006, 2007 2 PREFACE The arrangement of the present volume of the Inventories of Oriental manuscripts in Leiden University Library does not differ in any specific way from the volumes which have been published earlier (vols. 5, 6, 12, 13, 14, 20, 22 and 25). For the sake of brevity I refer to my prefaces in those volumes. A few essentials my be repeated here. Not all manuscripts mentioned in the present volume were viewed by autopsy. The sheer number of manuscripts makes this impossible.