IT Decision Making and the Business Manager Edward G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Entrepreneur's Guide to Doing Business in the Music Industry

THE ENTREPRENEUR’S GUIDE TO DOING BUSINESS IN THE MUSIC INDUSTRY by Gian Fiero Copyright 2005 by Gian Fiero All rights reserved. No part of this guide may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing by the author. ii iii Acknowledgements To all of my clients and the artists I’ve represented over the past 10 years: Thanks for choosing me when you have so many choices. I never forget that your trust in me is more valuable than any service I could ever offer. To my associates in Northern & Southern California: Thanks for the inspiration, encouragement, and support. iv v TABLE OF CONTENTS The Purpose of This Guide ...................................................................................... 1 Definition & Overview of This Guide....................................................................... 5 The Real Cash Cows of the Music Industry .........................................................11 Advice for the Potential Record Label Owner.......................................................15 Advice for Music Producers ...................................................................................19 Playing a Different Tune as a Music Artist ..........................................................23 Taking the Right Angle to Get a Deal ...................................................................29 Approaching Investors ...........................................................................................33 -

Position Description

Position Description Position Title: Business Manager Reports to: Chief Executive Officer Position Status: Full Time (Contract) Location: 95 Drummond Street, Carlton, VIC. 3053 ABOUT PENINGTON INSTITUTE Penington Institute advances health and community safety by connecting substance use research to practical action. Our activities: Enhance awareness of the health, social and economic drivers of drug-related harm. Promote rational, integrated approaches to reduce the burden of death, disease and social problems related to problematic substance use. Build and share knowledge to empower individuals, families and the community to take charge of substance use issues. Better equip front-line workers to respond effectively to the needs of those with problematic drug use. Our purpose is framed by our knowledge that we need to look at more effective, cost-efficient and compassionate ways to prevent and respond to problematic drug use in our community. Penington Institute acknowledges the importance of individual responsibility in relation to substance use, as well as the role of government and community to address the risks that contribute to problematic use of licit and illicit drugs and alcohol. Penington Institute is a non-partisan, registered charitable organisation. Our values Productivity: We support actions that deliver the best health, social and economic returns. Integrity: Drug use is a complex issue. We advocate fair, evidence-based systems that improve the health and wellbeing of individuals, families and communities. Compassion: We do not condone drug use, but work to protect people from drug-related harm when at their most vulnerable. Feasible and accessible options are needed to help reduce the risks associated with the use of different types of drugs, including pharmaceuticals, alcohol and nicotine. -

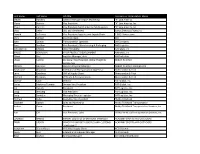

First Name Last Name Job Title Company Or Organization Name

First name Last name Job title Company or Organization Name Steven Hawkins General Manager Import Marketing "K" Line America Maria Bodnar Vice President "K" Line America, Inc. Shaun Gannon Vice President North America Field Logistics "K" Line America, Inc. Chas Deller CEO and CHAIRMAN 10XOCEANSOLUTIONS,INC Donald La France Vice President Logistics and Supply Chain 1-800-Flowers.com Chris McNeil Sourcing Agent 3M John Ladwig Transportation Specialist 3M Company Russ Boullion Vice President - Warehousing & Packaging A&R Logistics XIANGMING CHENG CEO/ PRESIDENT AAmetals, Inc BRUCE FERGUSON VP OF PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT AAmetals, Inc Eileen Wei Logistics Manager, Asia AB Electrolux Ulises Carrillo Divisional Vice President, Global Freight & Abbott Nutrition Distribution William Gaiennie Logistics Program Manager Abbott Nutrition International Sarah Jane Chapman International Transportation Supervisor Abercrombie & Fitch Larry Grischow GVP of Supply Chain Abercrombie & Fitch Michael Sherman VP Trade & Transportation Abercrombie & Fitch Gunnar Gose Director ABF Global, Inc. Carlos Martinez-Tomatis Division Vice President ABF Global, Inc. Jim Ingram President ABF Logistics, Inc. Doug Riesberg Vice President ABF Logistics, Inc. Craig Sandefur Managing Director Logistics ABF Logistics, Inc. Michael Kelso Executive Vice President Ability Tri-Modal Elizabeth Gaston Sales and Marketing Ability Tri-Modal Transportation Joshua Owen President Ability Tri-Modal Transportation Services, Inc. Ron Gill Vice President, Sales Ability/Tri-Modal Transportation Services, -

Retail Banking and Asset Management 20 Corporate and Investment Banking 32 Staff and Welfare Report 42 Our Share, Strategy and Outlook 48 Risk Report 54

annual report 2004 highlights of Commerzbank group 2004 2003 Income statement Operating profit (€ m) 1,043 559 Operating profit per share (€) 1.76 1.03 Pre-tax profit/loss (€ m) 828 –1,980 Net profit/loss (€ m) 393 –2,320 Net profit/loss per share (€) 0.66 –4.26 Operating return on equity (%) 10.2 4.9 Cost/income ratio in operating business (%) 70.4 73.3 Pre-tax return on equity (%) 8.1 –17.4 31.12.2004 31.12.2003 Balance sheet Balance-sheet total (€ bn) 424.9 381.6 Risk-weighted assets according to BIS (€ bn) 139.7 140.8 Equity as shown in balance sheet (€ bn) 9.8 9.1 Own funds as shown in balance sheet (€ bn) 19.9 19.7 BIS capital ratios Core capital ratio, excluding market-risk position (%) 7.8 7.6 Core capital ratio, including market-risk position (%) 7.5 7.3 Own funds ratio (%) 12.6 13.0 Commerzbank share Number of shares issued (million units) 598.6 597.9 Share price (€, 1.1.–31.12.) high 16.49 17.58 low 12.65 5.33 Book value per share*) (€) 18.53 17.37 Market capitalization (€ bn) 9.1 9.3 Customers 7,880,000 6,840,000 Staff Germany 25,417 25,426 Abroad 7,403 6,951 Total 32,820 32,377 Short/long-term rating Moody’s Investors Service, New York P-1/A2 P-1/A2 Standard & Poor’s, New York A-2/A- A-2/A- Fitch Ratings, London F2/A- F2/A- *) excluding cash flow hedges structure of commerzbank group Board of Managing Directors Corporate Divisions Group Retail Banking and Corporate and Services Management Asset Management Investment Banking Staff Banking Service departments departments departments G Accounting and Taxes G Asset Management -

Business Manager

THE COUNTY OF STANISLAUS DISTRICT ATTORNEY’S OFFICE Business Manager Manager I Manager II Manager III $57,803.20 - $86,715.20 $64,896.00 - $97,344.00 $73,382.40 - $110,073.60 Apply by November 24, 2020 Interviews are tentatively scheduled for the week of December 7th Business Manager The County of Stanislaus, District Attorney’s office seven Divisions with staff housed in several invites applications from qualified candidates for the locations and has approximately 147 employees and vacancy of a Business Manager. is comprised of full-time, part-time and contract employees. About the Community Stanislaus County is located in Central California The Position within 90 minutes of the San Francisco Bay Area, The District Attorney’s office is seeking an the Silicon Valley, Sacramento, the Sierra Nevada experienced, knowledgeable, and public service Mountains and California’s Central Coast. With an orientated Business Manager. The position is a estimated 545,267 people calling this area home, block-budgeted Manager I/II/III which reports directly the community reflects a region rich in diversity with to the District Attorney. The Business Manager is a strong sense of community. Two of responsible for managing the Departments’ California’s major north-south transportation routes operational, budget, and human resources (Interstate 5 and Highway 99) intersect the area and functions. the County has quickly become one of the dominant logistics center locations on the west Typical Duties and Responsibilities coast. • Advise department personnel on best practices in managing human resources; The County is home to a vibrant arts community with • Administer employee training programs, the world-class Gallo Center for the Arts, a including conducting annual training needs symphony orchestra, and abundant visual and assessment and coordinating course content and performing arts. -

Participant List

Participant List 10/20/2020 12:59:08 PM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jamal Aazizi Chargé de la logistique Association Tazghart Morocco Luz Abayan Program Officer Child Rights Coalition Asia Philippines Babak Abbaszadeh President And Chief Toronto Centre For Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership In Financial Supervision Amr Abdallah Director, Gulf Programs Education for Employment - United States EFE Ziad Abdel Samad Executive Director Arab NGO Network for Lebanon Development TAZI Abdelilah Président Associaion Talassemtane pour Morocco l'environnement et le développement ATED Abla Abdellatif Executive Director and The Egyptian Center for Egypt Director of Research Economic Studies Nabil Abdo MENA Senior Policy Oxfam International Lebanon Advisor Baako Abdul-Fatawu Executive Director Centre for Capacity Ghana Improvement for the Wellbeing of the Vulnerable (CIWED) Maryati Abdullah Director/National Publish What You Pay Indonesia Coordinator Indonesia Dr. Abel Executive Director Reach The Youth Uganda Switzerland Mwebembezi (RTY) Suchith Abeyewickre Ethics Education Arigatou International Sri Lanka me Programme Coordinator Diam Abou Diab Fellow Arab NGO Network for Lebanon Development Hayk Abrahamyan Community Organizer for International Accountability Armenia South Caucasus and Project Central Asia Aliyu Abubakar Secretary General Kano State Peace and Conflict Nigeria Resolution Association Sunil Acharya Regional Advisor, Climate Practical Action Nepal and Resilience Salim Adam Public Health -

Recently Closed Or Completed Positions Enquiries? Please Contact Us on 08 8212 0999 Or at [email protected]

Recently Closed or Completed Positions Enquiries? Please contact us on 08 8212 0999 or at [email protected] ▪ Graphic Designer (current assignment) ▪ Executive Assistant ▪ Executive Director (current assignment) ▪ Finance Manager ▪ Policy and Research Officer (current assignment) ▪ Marketing Manager ▪ Customer Service Officer (current assignment) ▪ Researcher ▪ Chief Executive Officer (current assignment) ▪ Procurement Officer ▪ Manager, Business Development (current assignment) ▪ Chief Executive Officer ▪ General Manager, Independent Living (current assignment) ▪ Chief Executive ▪ QES Systems Manager ▪ Chief Executive Officer ▪ Director, Corporate and Customer Service ▪ Business Transformation and Team Lead ▪ Project Architect ▪ IT Change and Project Manager ▪ Chief Operating Officer ▪ Supply Chain Manager ▪ Chief Financial Officer ▪ Senior Manager, Member Insurance and Account Services ▪ Senior Manager, Governance and Risk ▪ General Manager, Operations ▪ Business Development Executive ▪ Marketing and Events Officer ▪ Commercial Analyst ▪ General Manager Sales and Operations ▪ Director, Strategic Policy and Projects ▪ Dealership Financial Controller ▪ Marketing Specialist ▪ HSE Manager ▪ Human Resource Manager ▪ Project Scheduler ▪ Chief Executive Officer ▪ Control Centre Technician ▪ Dispute Resolution Officer ▪ Dispute Resolution Officer ▪ Chief Executive Officers – Six Regional Local Health Networks ▪ Architects ▪ Registered Psychologist ▪ Chief Information Officer ▪ Distribution Centre Supervisor ▪ Distribution Engineer -

Guy Morrow: Regulating Artist Managers

8 International Journal of Music Business Research, October 2013, vol. 2 no. 2 Regulating artist managers: An insider's perspective Guy Morrow1 Abstract It is problematic that artist managers in the international popular music industry are not currently subject to consistent regulatory frameworks, particularly given the increasing centralisation of responsibility with this role. This article examines the following research question: Can artist management practices be consistently regu- lated? In addition, it will address the following sub-research questions: What are the pitfalls that belie attempts to regulate for the betterment of musicians and the music industry? Is self-regulation a viable alternative? Keywords: Artist management, regulation, code of conduct Acknowledgement Many individuals have assisted and encouraged me throughout my research and work in artist management. I gratefully acknowledge the assistance of my co- manager, Rowan Brand, as well as the Boy & Bear band members: Killian Gavin, Ja- cob Tarasenko, David Hosking, Jon Hart and Tim Hart; without their support com- pletion of this article would not have been possible. Dr. Catherine Moore at New York University and Michael McMartin of Melody Management also provided valu- able advice and feed back. Furthermore, I received a Macquarie University New Staff Grant in 2009 that enabled me to travel and conduct research interviews and New York University graciously hosted me as a visiting scholar in 2010. 1 Guy Morrow was a visiting scholar at New York University where he studied artist management practices in the global economy with the International Music Managers' Forum and he currently has a Macquarie University Research Development Grant to research career development strategies within the new music industries. -

The Mechanics of Mecca: the Technopolitics of the Late Ottoman Hijaz and the Colonial Hajj

The Mechanics of Mecca: The Technopolitics of the Late Ottoman Hijaz and the Colonial Hajj Michael Christopher Low Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2015 © 2015 Michael Christopher Low All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The Mechanics of Mecca: The Technopolitics of the Late Ottoman Hijaz and the Colonial Hajj Michael Christopher Low Drawing on Ottoman and British archival sources as well as published materials in Arabic and modern Turkish, this dissertation analyzes how the Hijaz and the hajj to Mecca simultaneously became objects of Ottoman modernization, global public health, international law, and inter-imperial competition during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. I argue that from the early 1880s onward, Ottoman administrators embarked on an ambitious redefinition of the empire’s Arab tribal frontiers. Through modern engineering, technology, medicine, and ethnography, they set out to manage human life and the resources needed to sustain it, transform Bedouins into proper subjects, and gradually replace autonomous political life with more rigorous forms of territorial power. At the same time, with the advent of the steamship colonial regimes identified Mecca as the source of a “twin infection” of sanitary and security threats. Repeated outbreaks of cholera marked steamship-going pilgrimage traffic as a dangerous form of travel and a vehicle for the globalization of epidemic diseases. European, especially British Indian, officials feared that lengthy sojourns in Arabia might expose their Muslim subjects to radicalizing influences from diasporic networks of anti-colonial dissidents and pan-Islamic activists. -

Business Manager

Business Manager Position Summary: Under the supervision of the CEO, the Business Manager is responsible for all aspects of the business and office functions of the Y. The manager is responsible for leading and/or managing the operating functions to include: accounting, human resources, safety, budgeting, technology and administrative support for the Executive Director/CEO. Qualifications: • Must be a Cause-Driven Leader (focused on the mission and service to others) • Must have strong interpersonal, human relations and customer service skills. • Must have strong listening skills, coaching, and an ability to put people and relationships first. • Ability to relate effectively to diverse groups of people from all social and economic segments of the community. • Must be able to work autonomously within the Y’s core values of Caring, Honesty, Respect and Responsibility. • An understanding of the business transaction cycles: 1) point of sale to final collection, 2) purchase requisition to vendor payment, 3) employment hiring through payroll. • Must have excellent written and oral communication skills. • Must have effective conflict resolution skills and ability to maintain confidentiality. • Ability to respond to safety and emergency situations. • Demonstrated skills in planning, time management, flexibility, organization and independent work proficiency. • Excellent personal computer skills and experience with standard business software. • Ability to develop and use spreadsheets and standard systems at an intermediate level. • Bachelor’s degree in related field preferred or equivalent. • Experience with the Y or other not-for-profit organization preferred. • Ability to attend trainings and meetings as required even if scheduled outside normal working or regular scheduled hours. • Current CPR/AED certification or ability to become certified within first 60 days. -

Synergy ECP Corporate Overview

Corporate Overview January 2016 AGENDA Who we are • Organization Chart • NAICS Codes • Core Competencies • Contracts and Past Performance • Staff Certifications Our Synergetic Purpose Contact info Organization SYNERGY ECP Bruce Howard – CEO Dave Wisniewski – President Larry Hein Jim Howard Director of Business Development Information Technology Manager Laura Bodway Business Development Capital & Northern Regions Vern Lundskow Jason Augustino Business Development Director of Finance Southern Region Andrew Williams Director of Talent Acquisition Lindsay Cox Financial Analyst Jon Gallo Recruiter Jaime Wisniewski Business Manager Robin Greenberg Office Manager Larry Hein Laura Bodway Director of Cyber Advisory Division Director of Cyber Implementation Division Vacant Carlton Jackson Troy Scogland Steve Jordan Kevin Flint Section Manager Section Manager Section Manager Section Manager Section Manager Contractors Contractors Contractors Contractors Contractors NAICS Codes NAICS Code Description Size Standard 488119 Other Airport Operations $32.5M 488190 Other Support Activities for Air Transportation $32.5M 517919 All Other Telecommunications $32.5M 518210 Data Processing, Hosting and Related Services $32.5M 541219 Other Accounting Services $20.5M 541330 Engineering Services $15.0M/$38.5M 541430 Graphic Design Services $7.5M 541490 Other Specialized Design Services $7.5M 541511 Custom Computer Programming Services $27.5M 541512 Computer Systems Design Services $27.5M 541513 Computer Facilities Management Services $27.5M 541519 Other Computer -

(HR) Business Operations Manager Is Responsible

HUMAN RESOURCES BUSINESS OPERATIONS MANAGER Position Summary The Human Resources (HR) Business Operations Manager is responsible for the effective and consistent coordination and implementation of HR business processes, functions and procedures and monitors HR projects and workflow. On a regular and continuous basis, exercises administrative judgment on establishing departmental operation goals, standards, policies and procedures. Supervisory Relationship This position reports to the Director of Human Resources and interacts with other departments, administrators and staff District-wide. This position coordinates the work produced by HR Generalists, Specialists and other department staff in order to ensure completion of projects. Essential Functions Plans, organizes, and coordinates the operations and activities related to the Human Resources (HR) operations and functions on a District-wide level. Supports HR staff to resolve human resource problems, interpret HR policies and procedures and recommends effective courses of action. Provides leadership in coordinating the activities of the HR Department to ensure compliance with all applicable laws, policies, regulations and collective bargaining agreements. Works closely with Payroll and other HR staff in developing, implementing and evaluating ongoing HR/Payroll programs, functions and activities. Provides consistent interpretation/application of HR policies and procedures across the District. Identifies optimal solutions that meet the needs of the HR functions by recommending process