Volume 2, No 2, October 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DT MAIN FILE 1/25/99 7:51 PM Page 1

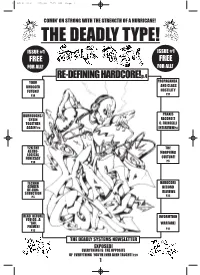

DT MAIN FILE 1/25/99 7:51 PM Page 1 COMINÕ ON STRONG WITH THE STRENGTH OF A HURRICANE! THE DEADLY TYPE! ISSUE #1 ISSUE #1 FREE FREE FOR ALL!L FOR ALL!L RE-DEFINING HARDCORE!p.4 YOUR PROPAGANDA DRUGGED AND CLASS FUTURE! HOSTILITY P.14 P.11 BURROUGHS/ PRAXIS GYSIN RECORD'S TOGETHER C. FRINGELLI AGAIN! P.6 INTERVIEWP.8 Y2K:THE THE ASTRO- MORPHING LOGICAL FORECAST CULTURE! P.10 P.5 TECHNO HARDCORE GENDER RECORD DE-CON- STRUCTION REVIEWS P.5 P.16 READ BEFORE INFORMTION YOU GO...A "JAIL WARFARE! PRIMER! P.12 P.13 THE DEADLY SYSTEMS NEWSLETTER EXPOSED! EVERYTHING IS THE OPPOSITE OF EVERYTHING YOU'VE EVER BEEN TAUGHT! P.29 1 DT MAIN FILE 1/25/99 7:51 PM Page 2 money. So you could say that the rave scene was truly assimilated on just about all fronts by the mainstream. This WHY THE aggravated a problem of mis-concep- tion for the music itself . Most people being introduced to Hardcore had no idea about the ideas surrounding it-or DEADLY that there even were any! To most peo- ple, even a few making music they claimed was “hardcore”, it was just fast, noizy, and supposed to piss you off. This is retarded. Nothing can be further TYPE? from the truth, and that is why “The Deadly Type” exists today, to re-define Hardcore. Firstly, “RE” as to do it again, -by Deadly Buda as people are not even aware of it’s influences, history or forgot the entire The original reason for this social context. -

The Entrepreneur's Guide to Doing Business in the Music Industry

THE ENTREPRENEUR’S GUIDE TO DOING BUSINESS IN THE MUSIC INDUSTRY by Gian Fiero Copyright 2005 by Gian Fiero All rights reserved. No part of this guide may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing by the author. ii iii Acknowledgements To all of my clients and the artists I’ve represented over the past 10 years: Thanks for choosing me when you have so many choices. I never forget that your trust in me is more valuable than any service I could ever offer. To my associates in Northern & Southern California: Thanks for the inspiration, encouragement, and support. iv v TABLE OF CONTENTS The Purpose of This Guide ...................................................................................... 1 Definition & Overview of This Guide....................................................................... 5 The Real Cash Cows of the Music Industry .........................................................11 Advice for the Potential Record Label Owner.......................................................15 Advice for Music Producers ...................................................................................19 Playing a Different Tune as a Music Artist ..........................................................23 Taking the Right Angle to Get a Deal ...................................................................29 Approaching Investors ...........................................................................................33 -

![COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5125/complete-music-list-by-artist-no-of-tunes-6773-465125.webp)

COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ]

[ COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ] 001 PRODUCTIONS >> BIG BROTHER THEME 10CC >> ART FOR ART SAKE 10CC >> DREADLOCK HOLIDAY 10CC >> GOOD MORNING JUDGE 10CC >> I'M NOT IN LOVE {K} 10CC >> LIFE IS A MINESTRONE 10CC >> RUBBER BULLETS {K} 10CC >> THE DEAN AND I 10CC >> THE THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE 112 >> DANCE WITH ME 1200 TECHNIQUES >> KARMA 1910 FRUITGUM CO >> SIMPLE SIMON SAYS {K} 1927 >> IF I COULD {K} 1927 >> TELL ME A STORY 1927 >> THAT'S WHEN I THINK OF YOU 24KGOLDN >> CITY OF ANGELS 28 DAYS >> SONG FOR JASMINE 28 DAYS >> SUCKER 2PAC >> THUGS MANSION 3 DOORS DOWN >> BE LIKE THAT 3 DOORS DOWN >> HERE WITHOUT YOU {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> KRYPTONITE {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> LOSER 3 L W >> NO MORE ( BABY I'M A DO RIGHT ) 30 SECONDS TO MARS >> CLOSER TO THE EDGE 360 >> LIVE IT UP 360 >> PRICE OF FAME 360 >> RUN ALONE 360 FEAT GOSSLING >> BOYS LIKE YOU 3OH!3 >> DON'T TRUST ME 3OH!3 FEAT KATY PERRY >> STARSTRUKK 3OH!3 FEAT KESHA >> MY FIRST KISS 4 THE CAUSE >> AIN'T NO SUNSHINE 4 THE CAUSE >> STAND BY ME {K} 4PM >> SUKIYAKI 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> DON'T STOP 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> GIRLS TALK BOYS {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> LIE TO ME {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE'S KINDA HOT {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> TEETH 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> WANT YOU BACK 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> YOUNGBLOOD {K} 50 CENT >> 21 QUESTIONS 50 CENT >> AYO TECHNOLOGY 50 CENT >> CANDY SHOP 50 CENT >> IF I CAN'T 50 CENT >> IN DA CLUB 50 CENT >> P I M P 50 CENT >> PLACES TO GO 50 CENT >> WANKSTA 5000 VOLTS >> I'M ON FIRE 5TH DIMENSION -

MUSIC LIST Email: Info@Partytimetow Nsville.Com.Au

Party Time Page: 1 of 73 Issue: 1 Date: Dec 2019 JUKEBOX Phone: 07 4728 5500 COMPLETE MUSIC LIST Email: info@partytimetow nsville.com.au 1 THING by Amerie {Karaoke} 100 PERCENT PURE LOVE by Crystal Waters 1000 STARS by Natalie Bassingthwaighte {Karaoke} 11 MINUTES by Yungblud - Halsey 1979 by Good Charlotte {Karaoke} 1999 by Prince {Karaoke} 19TH NERVIOUS BREAKDOWN by The Rolling Stones 2 4 6 8 MOTORWAY by The Tom Robinson Band 2 TIMES by Ann Lee 20 GOOD REASONS by Thirsty Merc {Karaoke} 21 - GUNS by Greenday {Karaoke} 21 QUESTIONS by 50 Cent 22 by Lilly Allen {Karaoke} 24K MAGIC by Bruno Mars 3 by Britney Spears {Karaoke} 3 WORDS by Cheryl Cole {Karaoke} 3AM by Matchbox 20 {Karaoke} 4 EVER by The Veronicas {Karaoke} 4 IN THE MORNING by Gwen Stefani {Karaoke} 4 MINUTES by Madonna And Justin 40 MILES OF ROAD by Duane Eddy 409 by The Beach Boys 48 CRASH by Suzi Quatro 5 6 7 8 by Steps {Karaoke} 500 MILES by The Proclaimers {Karaoke} 60 MILES AN HOURS by New Order 65 ROSES by Wolverines 7 DAYS by Craig David {Karaoke} 7 MINUTES by Dean Lewis {Karaoke} 7 RINGS by Ariana Grande {Karaoke} 7 THINGS by Miley Cyrus {Karaoke} 7 YEARS by Lukas Graham {Karaoke} 8 MILE by Eminem 867-5309 JENNY by Tommy Tutone {Karaoke} 99 LUFTBALLOONS by Nena 9PM ( TILL I COME ) by A T B A B C by Jackson 5 A B C BOOGIE by Bill Haley And The Comets A BEAT FOR YOU by Pseudo Echo A BETTER WOMAN by Beccy Cole A BIG HUNK O'LOVE by Elvis A BUSHMAN CAN'T SURVIVE by Tania Kernaghan A DAY IN THE LIFE by The Beatles A FOOL SUCH AS I by Elvis A GOOD MAN by Emerson Drive A HANDFUL -

Popular Music, Stars and Stardom

POPULAR MUSIC, STARS AND STARDOM POPULAR MUSIC, STARS AND STARDOM EDITED BY STEPHEN LOY, JULIE RICKWOOD AND SAMANTHA BENNETT Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia ISBN (print): 9781760462123 ISBN (online): 9781760462130 WorldCat (print): 1039732304 WorldCat (online): 1039731982 DOI: 10.22459/PMSS.06.2018 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design by Fiona Edge and layout by ANU Press This edition © 2018 ANU Press All chapters in this collection have been subjected to a double-blind peer-review process, as well as further reviewing at manuscript stage. Contents Acknowledgements . vii Contributors . ix 1 . Popular Music, Stars and Stardom: Definitions, Discourses, Interpretations . 1 Stephen Loy, Julie Rickwood and Samantha Bennett 2 . Interstellar Songwriting: What Propels a Song Beyond Escape Velocity? . 21 Clive Harrison 3 . A Good Black Music Story? Black American Stars in Australian Musical Entertainment Before ‘Jazz’ . 37 John Whiteoak 4 . ‘You’re Messin’ Up My Mind’: Why Judy Jacques Avoided the Path of the Pop Diva . 55 Robin Ryan 5 . Wendy Saddington: Beyond an ‘Underground Icon’ . 73 Julie Rickwood 6 . Unsung Heroes: Recreating the Ensemble Dynamic of Motown’s Funk Brothers . 95 Vincent Perry 7 . When Divas and Rock Stars Collide: Interpreting Freddie Mercury and Montserrat Caballé’s Barcelona . -

Position Description

Position Description Position Title: Business Manager Reports to: Chief Executive Officer Position Status: Full Time (Contract) Location: 95 Drummond Street, Carlton, VIC. 3053 ABOUT PENINGTON INSTITUTE Penington Institute advances health and community safety by connecting substance use research to practical action. Our activities: Enhance awareness of the health, social and economic drivers of drug-related harm. Promote rational, integrated approaches to reduce the burden of death, disease and social problems related to problematic substance use. Build and share knowledge to empower individuals, families and the community to take charge of substance use issues. Better equip front-line workers to respond effectively to the needs of those with problematic drug use. Our purpose is framed by our knowledge that we need to look at more effective, cost-efficient and compassionate ways to prevent and respond to problematic drug use in our community. Penington Institute acknowledges the importance of individual responsibility in relation to substance use, as well as the role of government and community to address the risks that contribute to problematic use of licit and illicit drugs and alcohol. Penington Institute is a non-partisan, registered charitable organisation. Our values Productivity: We support actions that deliver the best health, social and economic returns. Integrity: Drug use is a complex issue. We advocate fair, evidence-based systems that improve the health and wellbeing of individuals, families and communities. Compassion: We do not condone drug use, but work to protect people from drug-related harm when at their most vulnerable. Feasible and accessible options are needed to help reduce the risks associated with the use of different types of drugs, including pharmaceuticals, alcohol and nicotine. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

The True Measure of Success Why David Howe Puts Honesty and Integrity First

JOURNALREAL ESTATE INSTITUTE OF NEW SOUTH WALES | SEP/OCT 2017 VOL 68/05 The true measure of success Why David Howe puts honesty and integrity first PROFESSIONALISM CELEBRATING EXCELLENCE HANDLING A HACK Examining our professional identity Awards for Excellence finalists revealed Be alert and alarmed about cyber crime INSIDE REAL ESTATE JOURNAL The Real Estate Journal is the official magazine of the Real Estate Institute of New South Wales. CONTENTS 30 To terminate or not 30-32 Wentworth Avenue UPFRONT to terminate? Sydney NSW 2000 5 A word from the President (02) 9264 2343 The NSW Small Business [email protected] 6 In brief Commissioner explains the www.reinsw.com.au complexities of managing 8 AGM notice Managing Editor a mixed-use tenancy. Cath Dickinson 8 Board of Directors’ Wordcraft Media election notice 32 Handling a hack: Be alert 0410 330 903 … and alarmed! [email protected] 9 Chapter Committees www.wordcraftmedia.com.au What you can do to minimise nomination notice the risk of your agency falling Advertising (02) 9264 2343 9 Division Committees victim to a cyber attack. [email protected] nomination notice 35 Cyber insurance 10 REINSW Professionalism Art Direction and Design Cyber risk is a major emerging Bird Project Think Tank 0414 332 146 risk for all agencies. Are you [email protected] covered? www.birdproject.com PERSPECTIVES 14 Braving the big chill Printing The annual Real Estate CMMA Digital and Print TRAINING AND www.cmma.com.au Sleep Out saw 180 agents EVENTS raise more than $277,000 36 Novice Auctioneers Photography for charity. -

Mediated Music Makers. Constructing Author Images in Popular Music

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto Laura Ahonen Mediated music makers Constructing author images in popular music Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki in auditorium XII, on the 10th of November, 2007 at 10 o’clock. Laura Ahonen Mediated music makers Constructing author images in popular music Finnish Society for Ethnomusicology Publ. 16. © Laura Ahonen Layout: Tiina Kaarela, Federation of Finnish Learned Societies ISBN 978-952-99945-0-2 (paperback) ISBN 978-952-10-4117-4 (PDF) Finnish Society for Ethnomusicology Publ. 16. ISSN 0785-2746. Contents Acknowledgements. 9 INTRODUCTION – UNRAVELLING MUSICAL AUTHORSHIP. 11 Background – On authorship in popular music. 13 Underlying themes and leading ideas – The author and the work. 15 Theoretical framework – Constructing the image. 17 Specifying the image types – Presented, mediated, compiled. 18 Research material – Media texts and online sources . 22 Methodology – Social constructions and discursive readings. 24 Context and focus – Defining the object of study. 26 Research questions, aims and execution – On the work at hand. 28 I STARRING THE AUTHOR – IN THE SPOTLIGHT AND UNDERGROUND . 31 1. The author effect – Tracking down the source. .32 The author as the point of origin. 32 Authoring identities and celebrity signs. 33 Tracing back the Romantic impact . 35 Leading the way – The case of Björk . 37 Media texts and present-day myths. .39 Pieces of stardom. .40 Single authors with distinct features . 42 Between nature and technology . 45 The taskmaster and her crew. -

Utopian Ecomusicologies and Musicking Hornby Island

WHAT IS MUSIC FOR?: UTOPIAN ECOMUSICOLOGIES AND MUSICKING HORNBY ISLAND ANDREW MARK A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, CANADA August, 2015 © Andrew Mark 2015 Abstract This dissertation concerns making music as a utopian ecological practice, skill, or method of associative communication where participants temporarily move towards idealized relationships between themselves and their environment. Live music making can bring people together in the collective present, creating limited states of unification. We are “taken” by music when utopia is performed and brought to the present. From rehearsal to rehearsal, band to band, year to year, musicking binds entire communities more closely together. I locate strategies for community solidarity like turn-taking, trust-building, gift-exchange, communication, fundraising, partying, education, and conflict resolution as plentiful within musical ensembles in any socially environmentally conscious community. Based upon 10 months of fieldwork and 40 extended interviews, my theoretical assertions are grounded in immersive ethnographic research on Hornby Island, a 12-square-mile Gulf Island between mainland British Columbia and Vancouver Island, Canada. I describe how roughly 1000 Islanders struggle to achieve environmental resilience in a uniquely biodiverse region where fisheries collapsed, logging declined, and second-generation settler farms were replaced with vacation homes in the 20th century. Today, extreme gentrification complicates housing for the island’s vulnerable populations as more than half of island residents live below the poverty line. With demographics that reflect a median age of 62, young individuals, families, and children are squeezed out of the community, unable to reproduce Hornby’s alternative society. -

SYLLABUS Music 15

SYLLABUS Music 15 – Australian Popular Music Winter 2019 Lecture: Thursday 6:30-9:20pm, SOLIS 107 Final Exam: March 19th, 7pm Professor: Fiona Digney – [email protected] Office Hours: Fridays 2:00–5:00pm, or by appointment, CPMC 155 Teaching Assistants: Berk Schneider - [email protected] Sections: A01 (Monday 10:00am CPMC 136) A02 (Monday 11:00am CPMC 136) Office Hours: TBD Barbara Byers - [email protected] Sections: A03 (Wednesday 11:00am, CPMC 136) A04 (Wednesday 12:00pm, CPMC 136) Office Hours: TBD Juliana Gaona - [email protected] Sections: A05 (Friday 10:00am CPMC 145) A06 (Friday 11:00am CPMC 145) Office Hours: TBD Stephen De-Filippo - [email protected] Sections: A07 (Friday 12:00pm CPMC 145) A08 (Friday 1:00pm CPMC 145) Office Hours: TBD General Overview For a very large country with a relatively small population, Australian popular musicians have had great success worldwide. From ACDC, Skyhooks, Midnight Oil, Jimmy Barnes, and Kylie Minogue, to Temper Trap, Pendulum, Tame Impala, Sia, and Vance Joy, Australians have set out to change the history of music. This course will explore the political and social landscapes that made way for, and were created by these artists, including the Whitlam government initiatives, Triple J radio station, pub rock, and the culture of mateship. Prerequisite: None. Assessment 15% Attendance, preparation, and participation Attendance will be taken at all discussion sections. It is expected you have read and listened to all required materials. Arrive prepared to contribute in discussions. 30% Quizzes Three short quizzes are to be completed online through TritonED. They will be administered weeks four (due: February 3rd), six (due: February 17th), and eight (due: March 3rd). -

Ready Player One by Ernest Cline

Ready Player One by Ernest Cline Chapter 1 Everyone my age remembers where they were and what they were doing when they first heard about the contest. I was sitting in my hideout watching cartoons when the news bulletin broke in on my video feed, announcing that James Halliday had died during the night. I’d heard of Halliday, of course. Everyone had. He was the videogame designer responsible for creating the OASIS, a massively multiplayer online game that had gradually evolved into the globally networked virtual reality most of humanity now used on a daily basis. The unprecedented success of the OASIS had made Halliday one of the wealthiest people in the world. At first, I couldn’t understand why the media was making such a big deal of the billionaire’s death. After all, the people of Planet Earth had other concerns. The ongoing energy crisis. Catastrophic climate change. Widespread famine, poverty, and disease. Half a dozen wars. You know: “dogs and cats living together … mass hysteria!” Normally, the newsfeeds didn’t interrupt everyone’s interactive sitcoms and soap operas unless something really major had happened. Like the outbreak of some new killer virus, or another major city vanishing in a mushroom cloud. Big stuff like that. As famous as he was, Halliday’s death should have warranted only a brief segment on the evening news, so the unwashed masses could shake their heads in envy when the newscasters announced the obscenely large amount of money that would be doled out to the rich man’s heirs. 2 But that was the rub.