Guy Morrow: Regulating Artist Managers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Entrepreneur's Guide to Doing Business in the Music Industry

THE ENTREPRENEUR’S GUIDE TO DOING BUSINESS IN THE MUSIC INDUSTRY by Gian Fiero Copyright 2005 by Gian Fiero All rights reserved. No part of this guide may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing by the author. ii iii Acknowledgements To all of my clients and the artists I’ve represented over the past 10 years: Thanks for choosing me when you have so many choices. I never forget that your trust in me is more valuable than any service I could ever offer. To my associates in Northern & Southern California: Thanks for the inspiration, encouragement, and support. iv v TABLE OF CONTENTS The Purpose of This Guide ...................................................................................... 1 Definition & Overview of This Guide....................................................................... 5 The Real Cash Cows of the Music Industry .........................................................11 Advice for the Potential Record Label Owner.......................................................15 Advice for Music Producers ...................................................................................19 Playing a Different Tune as a Music Artist ..........................................................23 Taking the Right Angle to Get a Deal ...................................................................29 Approaching Investors ...........................................................................................33 -

Position Description

Position Description Position Title: Business Manager Reports to: Chief Executive Officer Position Status: Full Time (Contract) Location: 95 Drummond Street, Carlton, VIC. 3053 ABOUT PENINGTON INSTITUTE Penington Institute advances health and community safety by connecting substance use research to practical action. Our activities: Enhance awareness of the health, social and economic drivers of drug-related harm. Promote rational, integrated approaches to reduce the burden of death, disease and social problems related to problematic substance use. Build and share knowledge to empower individuals, families and the community to take charge of substance use issues. Better equip front-line workers to respond effectively to the needs of those with problematic drug use. Our purpose is framed by our knowledge that we need to look at more effective, cost-efficient and compassionate ways to prevent and respond to problematic drug use in our community. Penington Institute acknowledges the importance of individual responsibility in relation to substance use, as well as the role of government and community to address the risks that contribute to problematic use of licit and illicit drugs and alcohol. Penington Institute is a non-partisan, registered charitable organisation. Our values Productivity: We support actions that deliver the best health, social and economic returns. Integrity: Drug use is a complex issue. We advocate fair, evidence-based systems that improve the health and wellbeing of individuals, families and communities. Compassion: We do not condone drug use, but work to protect people from drug-related harm when at their most vulnerable. Feasible and accessible options are needed to help reduce the risks associated with the use of different types of drugs, including pharmaceuticals, alcohol and nicotine. -

First Name Last Name Job Title Company Or Organization Name

First name Last name Job title Company or Organization Name Steven Hawkins General Manager Import Marketing "K" Line America Maria Bodnar Vice President "K" Line America, Inc. Shaun Gannon Vice President North America Field Logistics "K" Line America, Inc. Chas Deller CEO and CHAIRMAN 10XOCEANSOLUTIONS,INC Donald La France Vice President Logistics and Supply Chain 1-800-Flowers.com Chris McNeil Sourcing Agent 3M John Ladwig Transportation Specialist 3M Company Russ Boullion Vice President - Warehousing & Packaging A&R Logistics XIANGMING CHENG CEO/ PRESIDENT AAmetals, Inc BRUCE FERGUSON VP OF PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT AAmetals, Inc Eileen Wei Logistics Manager, Asia AB Electrolux Ulises Carrillo Divisional Vice President, Global Freight & Abbott Nutrition Distribution William Gaiennie Logistics Program Manager Abbott Nutrition International Sarah Jane Chapman International Transportation Supervisor Abercrombie & Fitch Larry Grischow GVP of Supply Chain Abercrombie & Fitch Michael Sherman VP Trade & Transportation Abercrombie & Fitch Gunnar Gose Director ABF Global, Inc. Carlos Martinez-Tomatis Division Vice President ABF Global, Inc. Jim Ingram President ABF Logistics, Inc. Doug Riesberg Vice President ABF Logistics, Inc. Craig Sandefur Managing Director Logistics ABF Logistics, Inc. Michael Kelso Executive Vice President Ability Tri-Modal Elizabeth Gaston Sales and Marketing Ability Tri-Modal Transportation Joshua Owen President Ability Tri-Modal Transportation Services, Inc. Ron Gill Vice President, Sales Ability/Tri-Modal Transportation Services, -

Retail Banking and Asset Management 20 Corporate and Investment Banking 32 Staff and Welfare Report 42 Our Share, Strategy and Outlook 48 Risk Report 54

annual report 2004 highlights of Commerzbank group 2004 2003 Income statement Operating profit (€ m) 1,043 559 Operating profit per share (€) 1.76 1.03 Pre-tax profit/loss (€ m) 828 –1,980 Net profit/loss (€ m) 393 –2,320 Net profit/loss per share (€) 0.66 –4.26 Operating return on equity (%) 10.2 4.9 Cost/income ratio in operating business (%) 70.4 73.3 Pre-tax return on equity (%) 8.1 –17.4 31.12.2004 31.12.2003 Balance sheet Balance-sheet total (€ bn) 424.9 381.6 Risk-weighted assets according to BIS (€ bn) 139.7 140.8 Equity as shown in balance sheet (€ bn) 9.8 9.1 Own funds as shown in balance sheet (€ bn) 19.9 19.7 BIS capital ratios Core capital ratio, excluding market-risk position (%) 7.8 7.6 Core capital ratio, including market-risk position (%) 7.5 7.3 Own funds ratio (%) 12.6 13.0 Commerzbank share Number of shares issued (million units) 598.6 597.9 Share price (€, 1.1.–31.12.) high 16.49 17.58 low 12.65 5.33 Book value per share*) (€) 18.53 17.37 Market capitalization (€ bn) 9.1 9.3 Customers 7,880,000 6,840,000 Staff Germany 25,417 25,426 Abroad 7,403 6,951 Total 32,820 32,377 Short/long-term rating Moody’s Investors Service, New York P-1/A2 P-1/A2 Standard & Poor’s, New York A-2/A- A-2/A- Fitch Ratings, London F2/A- F2/A- *) excluding cash flow hedges structure of commerzbank group Board of Managing Directors Corporate Divisions Group Retail Banking and Corporate and Services Management Asset Management Investment Banking Staff Banking Service departments departments departments G Accounting and Taxes G Asset Management -

Barrett Vol 1.Pdf

Introduction usician, psychedelic explorer, eccentric, cult icon – Roger “Syd” Barrett was many things to many people. Created in conjunction with the Barrett family and The Estate of Roger Barrett, who have provided unprece- dented access to family photographs, artworks, and mem- Mories, Barrett offers an intimate portrait of the Syd known only to his family and closest friends. Previously unseen photographs taken on seaside holidays and other family occasions show us a happy and loving young man, smiling energetically in images that map his early life, from childhood through his teenage years. Along with newly available photos from the album cover shoots for The Madcap Laughs and Barrett (taken by Storm Thorgerson and Mick Rock) they reveal the positive energy of a grinning Syd as he fools about in front of the camera. We are offered a rare glimpse of one who was immensely popular among friends and contemporaries. Also contained within these pages are recently unearthed images of Pink Floyd in which we see Syd practising handstands, making muscle-man poses, and having fun. The other members of Floyd lark about too – a fledgling young band enjoying itself with a sense of real camaraderie. The images transport one back in time to 166–67: the London Free School gigs, the launch of International Times at the Roundhouse, the UFO club, the band’s first European dates. There are photos of Syd and Floyd at numerous locations and events, giving a real sense of what it must have been like to be there as the infant light shows, experimentation, and collective spirit of the time emerged, grew, and flourished in the psychedelic hothouse that was the late 160s. -

Full Recording History Of

Why Are We Sleeping Joy Of A Toy The Recording Sessions WAWS is indebted to DAVID PARKER for a detailed and previously unpublished insight into the 1969 Abbey Road recording sessions that culminated in the now familiar masterpiece. This was originally planned as a ‘Why Are We Sleeping’ Special issue but the right moment and the required energy were running on parallel lines destined never to meet……………. Until now Stop that train To celebrate the imminent reissue of the Harvest classic, these details are intended to make your enjoyment complete. MW April 2003 The ‘Joy of a Toy’ Recording Sessions It was all a bit of a mistake on my part really. I had started the long-winded process of chronicling the recording sessions of my hero Syd Barrett, for an article or two in ‘Chapter 24’; a dull, forbidding read of a fanzine put out by myself and John Kelly. At some, now long forgotten, point I was introduced to the wonderful world of WAWS; a fanzine, which resembles what ‘Chapter 24’ would probably be like if our hero still did gigs, played an occasional radio session, wrote songs and released new recordings. In one of those rare and dangerous moments of bonhomie that come back to haunt one later in life, I suggested to Martin that I might be able to find the time to knock up a short piece about Mr Ayer’s recording sessions at Abbey Road. Little did I know what I was letting myself in for! Still, here is the first chunk, and I hope you find it interesting. -

Business Manager

THE COUNTY OF STANISLAUS DISTRICT ATTORNEY’S OFFICE Business Manager Manager I Manager II Manager III $57,803.20 - $86,715.20 $64,896.00 - $97,344.00 $73,382.40 - $110,073.60 Apply by November 24, 2020 Interviews are tentatively scheduled for the week of December 7th Business Manager The County of Stanislaus, District Attorney’s office seven Divisions with staff housed in several invites applications from qualified candidates for the locations and has approximately 147 employees and vacancy of a Business Manager. is comprised of full-time, part-time and contract employees. About the Community Stanislaus County is located in Central California The Position within 90 minutes of the San Francisco Bay Area, The District Attorney’s office is seeking an the Silicon Valley, Sacramento, the Sierra Nevada experienced, knowledgeable, and public service Mountains and California’s Central Coast. With an orientated Business Manager. The position is a estimated 545,267 people calling this area home, block-budgeted Manager I/II/III which reports directly the community reflects a region rich in diversity with to the District Attorney. The Business Manager is a strong sense of community. Two of responsible for managing the Departments’ California’s major north-south transportation routes operational, budget, and human resources (Interstate 5 and Highway 99) intersect the area and functions. the County has quickly become one of the dominant logistics center locations on the west Typical Duties and Responsibilities coast. • Advise department personnel on best practices in managing human resources; The County is home to a vibrant arts community with • Administer employee training programs, the world-class Gallo Center for the Arts, a including conducting annual training needs symphony orchestra, and abundant visual and assessment and coordinating course content and performing arts. -

May Newsletter MASTER.Indd

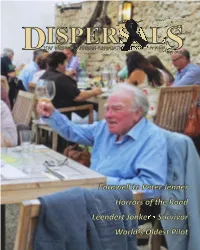

2nd TACTICAL AIR FORCE MEDIUM BOMBERS ASSOCIATION Incorporating 88, 98, 107, 180, 226, 305, 320, & 342 Squadrons 137 & 139 Wings, 2 Group RAF MBA Canada Executive Chairman/Newsletter Editor David Poissant 1980 Imperial Way, #402, Burlington, ON L7L 0E7 Telephone: 905-331-3038 E-mail: [email protected] Secretary/Treasurer Susan MacKenzie 406 Devine Street, Sarnia, ON N7T 1V5 Telephone: 519-332-2765 E-mail: [email protected] Western Representative Lynda Lougheed PO Box 54 Spruce View, AB T0M 1V0 Telephone: 403-728-2333 E-mail: [email protected] Eastern Representative Darrell Bing 75 Baroness Close, Hammond Plains, NS B4B 0B4 Telephone: 902-463-7419 E-mail: [email protected] MBA United Kingdom Executive Chairman/Liason To Be Announced Secretary/Archivist Russell Legross 15 Holland Park Drive, Hedworth Estate, Jarrow, Tyne & Wear NE32 4LL Telephone: 0191 4569840 E-mail: [email protected] Treasurer Frank Perriam 3a Farm Way, Worcester Park, Surrey KT4 8RU Telephone: 07587 366371 E-mail: [email protected] Registrar John D. McDonald 35 Mansted Gardens, Chadwell Heath, Romford, Essex RM6 4ED Telephone: 020 8590 2524 E-mail: [email protected] Newsletter Editor To Be Announced Contact Sectretary (Russell Legross) in interim. MBA Executive - Australia Secretary Tricia Williams PO Box 304, Brighton 3186, Australia Telephone: +61 422 581 028 E-mail: [email protected] DISPERSALS is published February Ɣ May Ɣ August Ɣ November On our cover: Peter Jenner toasts tablemates at dinner in Vienna with family and friends. Photo by Tricia Williams (2TAF MBA Secretary, Australia) CHAIRMAN’S NOTES • MAY 2016 This issue of Dispersals marks the passing of two Second Tactical Air Force Medium Bombers Association stalwarts: George Smith and Peter Jenner. -

Allmusic ((( the Pink Floyd and Syd Barrett Story > Overview

allmusic ((( The Pink Floyd and Syd Barrett Story > Overview ))) http://www.allmusic.com/cg/amg.dll?p=amg&token=&sql=10:h9fyxq8sldae You know your music - so do we. THE ALLMUSIC BLOG » New Releases » Editors' Choice » Music Videos » Writers' Bloc » Top Searches » Whole Note » Classical Corner » Artist Spotlight » Top Composers » Classical Reviews Artist/Group 6 You are not logged in. Login or Register Overview Review Credits Chart & Awards Buy Send to The Pink Floyd and Syd Barrett Story Friend Pink Floyd & Syd Barrett Review by Richie Unterberger In a couple important respects, Syd Barrett is a difficult documentary subject, as there isn't much film of him either performing or being interviewed. The 50-minute film (originally broadcast on the BBC) that's the main feature of this DVD, however, does an excellent job of summarizing the key aspects of his life and music. Its most important strength is its interviews with his close associates, scoring the hard-to-believe coup of first-hand talks with all four of Barrett's Pink Floyd bandmates (Roger Waters, Nick Mason, Rick Wright, and David Gilmour). Making briefer but meaningful contributions are such interesting figures as Bob Klose, Pink Floyd's original guitarist; early Barrett girlfriend Libby Chisman; early Pink Floyd co-manager Peter Jenner; and Mike Leonard, who worked on the group's early lighting Available On: effects. Mixed with those interviews are small but significant snippets of '60s footage Priced from $10.48 to $29.99 See all 6 sellers showing Barrett in performance with Pink Floyd, live and in the studio, as well as excerpts from home movies and the "Arnold Layne" promotional video; there's even a bit of the Album Browser legendary unreleased Floyd/Barrett song "Vegetable Man" on the soundtrack. -

Pink Floyd Sogni E Visioni Stellari Anselmo Patacchini

Pink Floyd Sogni e visioni stellari Anselmo Patacchini rassegna domenicale The Spontaneous Underground organizzata dal duo Steve Stollman e da John Hopkins. I Pink Floyd si cimentarono in lunghe e sconvolgenti versioni di Roadrunner e di altri pezzi di Chuck Berry, divertendosi, inoltre, a sovrapporre strati di feedback a volume altissimo. Peter Jenner (professore alla London School Of Economics) e l'amico Andrew King rimasero inebriati da quelle sonorità fuori dagli schemi e decisero di puntare su quei quattro talentuosi ragazzi a tal punto da formare assieme a loro la Blackhill Enterprises, società che avrebbe curato il management. Il 15 ottobre i Pink Floyd, o meglio, la Pink Floyd Steel Band - così annunciavano le locandine dell'epoca - assieme ai Soft Machine «Il sole splende sul mio cuscino/più Questo articolo, che riporta le fasi - gruppo di punta - si cimentarono salienti della lunga carriera dei mitici alla Roundhouse (una vecchia soffice di un piumino.../Vorrei che il Pink Floyd dagli esordi sino al 1969, stazione ferroviaria londinese in salice piangente agitasse intorno i vuole essere un doveroso omaggio disuso) che festeggiava con uno rami.../Sogno Julia/la sogno regina, alla figura di Syd Barrett, il geniale scatenato All Night-Rave la nascita artista passato a miglior vita lo dell'International Times (IT), la regina di tutti i miei sogni...» scorso 7 luglio. Ci piace ancora prima rivista underground nel ricordarlo come autore Regno Unito. Oltre duemila persone (Syd Barrett da Julia Dream) d’incantesimi stravolgenti, adornato si accalcarono all'interno del locale. da pantaloni a zampa d’elefante, Gente comune e bizzarra mischiata camicie sgargianti e una folta a personaggi famosi come il regista chioma che gli scendeva sulle Michelangelo Antonioni spalle, tra boccoli di capelli arruffati, accompagnato da Monica Vitti o con quei suoi occhi spaesati a Paul McCartney che si presentò costruire idealmente spazi vestito da arabo con tanto di tunica immaginari e infinite dimensioni. -

Participant List

Participant List 10/20/2020 12:59:08 PM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jamal Aazizi Chargé de la logistique Association Tazghart Morocco Luz Abayan Program Officer Child Rights Coalition Asia Philippines Babak Abbaszadeh President And Chief Toronto Centre For Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership In Financial Supervision Amr Abdallah Director, Gulf Programs Education for Employment - United States EFE Ziad Abdel Samad Executive Director Arab NGO Network for Lebanon Development TAZI Abdelilah Président Associaion Talassemtane pour Morocco l'environnement et le développement ATED Abla Abdellatif Executive Director and The Egyptian Center for Egypt Director of Research Economic Studies Nabil Abdo MENA Senior Policy Oxfam International Lebanon Advisor Baako Abdul-Fatawu Executive Director Centre for Capacity Ghana Improvement for the Wellbeing of the Vulnerable (CIWED) Maryati Abdullah Director/National Publish What You Pay Indonesia Coordinator Indonesia Dr. Abel Executive Director Reach The Youth Uganda Switzerland Mwebembezi (RTY) Suchith Abeyewickre Ethics Education Arigatou International Sri Lanka me Programme Coordinator Diam Abou Diab Fellow Arab NGO Network for Lebanon Development Hayk Abrahamyan Community Organizer for International Accountability Armenia South Caucasus and Project Central Asia Aliyu Abubakar Secretary General Kano State Peace and Conflict Nigeria Resolution Association Sunil Acharya Regional Advisor, Climate Practical Action Nepal and Resilience Salim Adam Public Health -

Recently Closed Or Completed Positions Enquiries? Please Contact Us on 08 8212 0999 Or at [email protected]

Recently Closed or Completed Positions Enquiries? Please contact us on 08 8212 0999 or at [email protected] ▪ Graphic Designer (current assignment) ▪ Executive Assistant ▪ Executive Director (current assignment) ▪ Finance Manager ▪ Policy and Research Officer (current assignment) ▪ Marketing Manager ▪ Customer Service Officer (current assignment) ▪ Researcher ▪ Chief Executive Officer (current assignment) ▪ Procurement Officer ▪ Manager, Business Development (current assignment) ▪ Chief Executive Officer ▪ General Manager, Independent Living (current assignment) ▪ Chief Executive ▪ QES Systems Manager ▪ Chief Executive Officer ▪ Director, Corporate and Customer Service ▪ Business Transformation and Team Lead ▪ Project Architect ▪ IT Change and Project Manager ▪ Chief Operating Officer ▪ Supply Chain Manager ▪ Chief Financial Officer ▪ Senior Manager, Member Insurance and Account Services ▪ Senior Manager, Governance and Risk ▪ General Manager, Operations ▪ Business Development Executive ▪ Marketing and Events Officer ▪ Commercial Analyst ▪ General Manager Sales and Operations ▪ Director, Strategic Policy and Projects ▪ Dealership Financial Controller ▪ Marketing Specialist ▪ HSE Manager ▪ Human Resource Manager ▪ Project Scheduler ▪ Chief Executive Officer ▪ Control Centre Technician ▪ Dispute Resolution Officer ▪ Dispute Resolution Officer ▪ Chief Executive Officers – Six Regional Local Health Networks ▪ Architects ▪ Registered Psychologist ▪ Chief Information Officer ▪ Distribution Centre Supervisor ▪ Distribution Engineer