Aquatic Adaptation of a Laterally Acquired Pectin Degradation Pathway in Marine Gammaproteobacteria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sulfite Dehydrogenases in Organotrophic Bacteria : Enzymes

Sulfite dehydrogenases in organotrophic bacteria: enzymes, genes and regulation. Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades des Doktors der Naturwissenschaften (Dr. rer. nat.) an der Universität Konstanz Fachbereich Biologie vorgelegt von Sabine Lehmann Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 10. April 2013 1. Referent: Prof. Dr. Bernhard Schink 2. Referent: Prof. Dr. Andrew W. B. Johnston So eine Arbeit wird eigentlich nie fertig, man muss sie für fertig erklären, wenn man nach Zeit und Umständen das möglichste getan hat. (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Italienische Reise, 1787) DANKSAGUNG An dieser Stelle möchte ich mich herzlich bei folgenden Personen bedanken: . Prof. Dr. Alasdair M. Cook (Universität Konstanz, Deutschland), der mir dieses Thema und seine Laboratorien zur Verfügung stellte, . Prof. Dr. Bernhard Schink (Universität Konstanz, Deutschland), für seine spontane und engagierte Übernahme der Betreuung, . Prof. Dr. Andrew W. B. Johnston (University of East Anglia, UK), für seine herzliche und bereitwillige Aufnahme in seiner Arbeitsgruppe, seiner engagierten Unter- stützung, sowie für die Übernahme des Koreferates, . Prof. Dr. Frithjof C. Küpper (University of Aberdeen, UK), für seine große Hilfsbereitschaft bei der vorliegenden Arbeit und geplanter Manuskripte, als auch für die mentale Unterstützung während der letzten Jahre! Desweiteren möchte ich herzlichst Dr. David Schleheck für die Übernahme des Koreferates der mündlichen Prüfung sowie Prof. Dr. Alexander Bürkle, für die Übernahme des Prüfungsvorsitzes sowie für seine vielen hilfreichen Ratschläge danken! Ein herzliches Dankeschön geht an alle beteiligten Arbeitsgruppen der Universität Konstanz, der UEA und des SAMS, ganz besonders möchte ich dabei folgenden Personen danken: . Dr. David Schleheck und Karin Denger, für die kritische Durchsicht dieser Arbeit, der durch und durch sehr engagierten Hilfsbereitschaft bei Problemen, den zahlreichen wissenschaftlichen Diskussionen und für die aufbauenden Worte, . -

Dissimilation of Cysteate Via 3-Sulfolactate Sulfo-Lyase and a Sulfate Exporter in Paracoccus Pantotrophus NKNCYSA

Microbiology (2005), 151, 737–747 DOI 10.1099/mic.0.27548-0 Dissimilation of cysteate via 3-sulfolactate sulfo-lyase and a sulfate exporter in Paracoccus pantotrophus NKNCYSA Ulrike Rein,1 Ronnie Gueta,1 Karin Denger,1 Ju¨rgen Ruff,1 Klaus Hollemeyer2 and Alasdair M. Cook1 Correspondence 1Department of Biology, The University, D-78457 Konstanz, Germany Alasdair Cook 2Institute of Biochemical Engineering, Saarland University, Box 50 11 50, D-66041 [email protected] Saarbru¨cken, Germany Paracoccus pantotrophus NKNCYSA utilizes (R)-cysteate (2-amino-3-sulfopropionate) as a sole source of carbon and energy for growth, with either nitrate or molecular oxygen as terminal electron acceptor, and the specific utilization rate of cysteate is about 2 mkat (kg protein)”1. The initial degradative reaction is catalysed by an (R)-cysteate : 2-oxoglutarate aminotransferase, which yields 3-sulfopyruvate. The latter was reduced to 3-sulfolactate by an NAD-linked sulfolactate dehydrogenase [3?3 mkat (kg protein)”1]. The inducible desulfonation reaction was not detected initially in cell extracts. However, a strongly induced protein with subunits of 8 kDa (a) and 42 kDa (b) was found and purified. The corresponding genes had similarities to those encoding altronate dehydratases, which often require iron for activity. The purified enzyme could then be shown to convert 3-sulfolactate to sulfite and pyruvate and it was termed sulfolactate sulfo-lyase (Suy). A high level of sulfite dehydrogenase was also induced during growth with cysteate, and the organism excreted sulfate. A putative regulator, OrfR, was encoded upstream of suyAB on the reverse strand. Downstream of suyAB was suyZ, which was cotranscribed with suyB. -

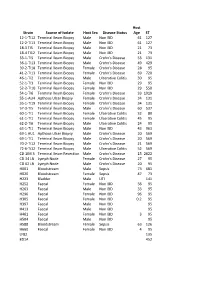

Strain Source of Isolate Host Sex Disease Status Host Age ST

Host Strain Source of Isolate Host Sex Disease Status Age ST 12-1-TI12 Terminal Ileum Biopsy Male Non IBD 61 127 12-2-TI13 Terminal Ileum Biopsy Male Non IBD 61 127 18-3 TI5 Terminal Ileum Biopsy Male Non IBD 21 73 18-4 TI12 Terminal Ileum Biopsy Male Non IBD 21 73 33-1-TI5 Terminal Ileum Biopsy Male Crohn's Disease 53 131 36-1-TI13 Terminal Ileum Biopsy Male Crohn's Disease 49 429 39-2-TI18 Terminal Ileum Biopsy Female Crohn's Disease 28 95 41-2-TI13 Terminal Ileum Biopsy Female Crohn's Disease 69 720 46-1-TI2 Terminal Ileum Biopsy Male Ulcerative Colitis 30 95 52-1-TI3 Terminal Ileum Biopsy Female Non IBD 29 95 52-2-TI10 Terminal Ileum Biopsy Female Non IBD 29 550 54-1-TI6 Terminal Ileum Biopsy Female Crohn's Disease 33 1919 55-1-AU4 Apthous Ulcer Biopsy Female Crohn's Disease 34 131 55-1-TI19 Terminal Ileum Biopsy Female Crohn's Disease 34 131 57-3-TI5 Terminal Ileum Biopsy Male Crohn's Disease 60 537 60-1-TI1 Terminal Ileum Biopsy Female Ulcerative Colitis 32 80 61-1-TI1 Terminal Ileum Biopsy Female Ulcerative Colitis 45 95 62-2-TI6 Terminal Ileum Biopsy Male Ulcerative Colitis 24 95 63-1-TI1 Terminal Ileum Biopsy Male Non IBD 43 963 69-1 AU1 Apthous Ulcer Biopsy Male Crohn's Disease 20 569 69-1-TI1 Terminal Ileum Biopsy Male Crohn's Disease 20 569 70-2-TI12 Terminal Ileum Biopsy Male Crohn's Disease 21 569 72-6-Ti12 Terminal Ileum Biopsy Male Ulcerative Colitis 52 569 CD 1IM 3 Terminal Ileum Resection Male Crohn's Disease 15 2622 CD 34 LN Lymph Node Female Crohn's Disease 27 95 CD 62 LN Lymph Node Male Crohn's Disease 20 95 H001 -

Novel Non-Phosphorylative Pathway of Pentose Metabolism from Bacteria

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Novel non-phosphorylative pathway of pentose metabolism from bacteria Received: 22 March 2018 Seiya Watanabe1,2,3, Fumiyasu Fukumori4, Hisashi Nishiwaki1,2, Yasuhiro Sakurai5, Accepted: 30 September 2018 Kunihiko Tajima5 & Yasuo Watanabe1,2 Published: xx xx xxxx Pentoses, including D-xylose, L-arabinose, and D-arabinose, are generally phosphorylated to D-xylulose 5-phosphate in bacteria and fungi. However, in non-phosphorylative pathways analogous to the Entner-Dodorof pathway in bacteria and archaea, such pentoses can be converted to pyruvate and glycolaldehyde (Route I) or α-ketoglutarate (Route II) via a 2-keto-3-deoxypentonate (KDP) intermediate. Putative gene clusters related to these metabolic pathways were identifed on the genome of Herbaspirillum huttiense IAM 15032 using a bioinformatic analysis. The biochemical characterization of C785_RS13685, one of the components encoded to D-arabinonate dehydratase, difered from the known acid-sugar dehydratases. The biochemical characterization of the remaining components and a genetic expression analysis revealed that D- and L-KDP were converted not only to α-ketoglutarate, but also pyruvate and glycolate through the participation of dehydrogenase and hydrolase (Route III). Further analyses revealed that the Route II pathway of D-arabinose metabolism was not evolutionally related to the analogous pathway from archaea. Te breakdown of D-glucose is central for energy and biosynthetic metabolism throughout all domains of life. Te most common glycolytic routes in bacteria are the Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas, the Entner-Doudorof (ED), and the oxidative pentose phosphate pathways. Te distinguishing diference between the two former glyco- lytic pathways lies in the nature of the 6-carbon metabolic intermediates that serve as substrates for aldol cleav- age. -

Within-Host Diversity of Multidrug-Resistant Escherichia Coli in the Gut and Bladder Sofiya G. Shevchenko a Dissertation Submitt

Within-host Diversity of Multidrug-Resistant Escherichia coli in the Gut and Bladder Sofiya G. Shevchenko A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2019 Reading committee: Evgeni Sokurenko, Chair John Mittler Kevin Hybiske Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Microbiology ©Copyright 2019 Sofiya G. Shevchenko University of Washington Abstract Within-host Diversity of Escherichia coli in the Gut and Bladder Sofiya G. Shevchenko Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Evgeni V. Sokurenko Department of Microbiology Uropathogenic E. coli are paradoxically able to both cause disease in the urinary tract, and reside there asymptomatically. The pandemic, multi-drug resistant E. coli subclone ST131-H30 (H30) is of special interest, as it has been found to persist in the gut and bladder of healthy people. In order to understand this persistence, we investigated whether H30 is competitive in these niches and thus able to persist by excluding other E. coli, as well as whether H30 may persist via within-host adaptation. In order to assess the E. coli clonal landscape, we developed a novel method based on deep sequencing of two loci, along with an algorithm for analysis of resulting data. Using this method, we assessed fecal and urinary samples from healthy women carrying H30, and found that even in the absence of antibiotic use, H30 could completely dominate the gut and, especially, urine of healthy carriers. In order to ascertain whether H30 adapts within- host, we employed population-level whole genome sequencing, and determined that H30 undergoes changes in genes affecting respiration in the gut, similar to commensal gut E. -

POLSKIE TOWARZYSTWO BIOCHEMICZNE Postępy Biochemii

POLSKIE TOWARZYSTWO BIOCHEMICZNE Postępy Biochemii http://rcin.org.pl WSKAZÓWKI DLA AUTORÓW Kwartalnik „Postępy Biochemii” publikuje artykuły monograficzne omawiające wąskie tematy, oraz artykuły przeglądowe referujące szersze zagadnienia z biochemii i nauk pokrewnych. Artykuły pierwszego typu winny w sposób syntetyczny omawiać wybrany temat na podstawie możliwie pełnego piśmiennictwa z kilku ostatnich lat, a artykuły drugiego typu na podstawie piśmiennictwa z ostatnich dwu lat. Objętość takich artykułów nie powinna przekraczać 25 stron maszynopisu (nie licząc ilustracji i piśmiennictwa). Kwartalnik publikuje także artykuły typu minireviews, do 10 stron maszynopisu, z dziedziny zainteresowań autora, opracowane na podstawie najnow szego piśmiennictwa, wystarczającego dla zilustrowania problemu. Ponadto kwartalnik publikuje krótkie noty, do 5 stron maszynopisu, informujące o nowych, interesujących osiągnięciach biochemii i nauk pokrewnych, oraz noty przybliżające historię badań w zakresie różnych dziedzin biochemii. Przekazanie artykułu do Redakcji jest równoznaczne z oświadczeniem, że nadesłana praca nie była i nie będzie publikowana w innym czasopiśmie, jeżeli zostanie ogłoszona w „Postępach Biochemii”. Autorzy artykułu odpowiadają za prawidłowość i ścisłość podanych informacji. Autorów obowiązuje korekta autorska. Koszty zmian tekstu w korekcie (poza poprawieniem błędów drukarskich) ponoszą autorzy. Artykuły honoruje się według obowiązujących stawek. Autorzy otrzymują bezpłatnie 25 odbitek swego artykułu; zamówienia na dodatkowe odbitki (płatne) należy zgłosić pisemnie odsyłając pracę po korekcie autorskiej. Redakcja prosi autorów o przestrzeganie następujących wskazówek: Forma maszynopisu: maszynopis pracy i wszelkie załączniki należy nadsyłać w dwu egzem plarzach. Maszynopis powinien być napisany jednostronnie, z podwójną interlinią, z marginesem ok. 4 cm po lewej i ok. 1 cm po prawej stronie; nie może zawierać więcej niż 60 znaków w jednym wierszu nie więcej niż 30 wierszy na stronie zgodnie z Normą Polską. -

Regulatory Role of Plar (Yiaj) for Plant Utilization in Escherichia Coli K-12

www.nature.com/scientificreports Corrected: Author Correction OPEN Regulatory Role of PlaR (YiaJ) for Plant Utilization in Escherichia coli K-12 Tomohiro Shimada 1,2*, Yui Yokoyama3, Takumi Anzai1, Kaneyoshi Yamamoto3 & Akira Ishihama2,3* Outside a warm-blooded animal host, the enterobacterium Escherichia coli K-12 is also able to grow and survive in stressful nature. The major organic substance in nature is plant, but the genetic system of E. coli how to utilize plant-derived materials as nutrients is poorly understood. Here we describe the set of regulatory targets for uncharacterized IclR-family transcription factor YiaJ on the E. coli genome, using gSELEX screening system. Among a total of 18 high-afnity binding targets of YiaJ, the major regulatory target was identifed to be the yiaLMNOPQRS operon for utilization of ascorbate from fruits and galacturonate from plant pectin. The targets of YiaJ also include the genes involved in the utilization for other plant-derived materials as nutrients such as fructose, sorbitol, glycerol and fructoselysine. Detailed in vitro and in vivo analyses suggest that L-ascorbate and α-D-galacturonate are the efector ligands for regulation of YiaJ function. These fndings altogether indicate that YiaJ plays a major regulatory role in expression of a set of the genes for the utilization of plant-derived materials as nutrients for survival. PlaR was also suggested to play protecting roles of E. coli under stressful environments in nature, including the formation of bioflm. We then propose renaming YiaJ to PlaR (regulator of plant utilization). Bacteria constantly monitor environmental conditions, and respond for adaptation and survival by modulating the expression pattern of their genomes. -

1471-2164-6-174-S4.PDF (299.1Kb)

Sup_Table_2. Comparison of the whole genomes in Fig. 3A. Segment 1- Conserved in Bm, Bp, and Bt to Bp to Bt Gene Description % length % identity % length % identity BMA0001 chromosomal replication initiator protein DnaA 100 99 100 96 BMA0002 DNA polymerase III, beta subunit 100 100 100 99 BMA0003 DNA gyrase, B subunit 100 100 100 99 BMA0006 carboxymuconolactone decarboxylase family protein 100 98 100 99 BMA0010 hypothetical protein 100 99 100 92 BMA0011 hypothetical protein 100 100 100 91 BMA0014.1 hypothetical protein 100 99 96 94 BMA0018 hypothetical protein 100 99 100 95 BMA0019 FHA domain protein 100 100 100 94 BMA0020 protein kinase domain protein 100 99 100 90 BMA0023 conserved hypothetical protein 100 99 100 90 BMA0024 aldolase, class II 100 98 100 91 BMA0027 polysaccharide biosynthesis family protein 100 100 100 96 BMA0028 glycosyl transferase, group 1 family protein 100 99 100 94 BMA0029 mannose-1-phosphate guanylyltransferase/mannose-6-phosphate isomerase 100 99 100 92 BMA0030 ElaA family protein 100 99 100 90 BMA0032 glycosyl transferase, group 1 family protein 100 99 100 93 BMA0037 sigma-54 dependent transcriptional regulator 100 99 100 97 BMA0039 beta-mannosidase-related protein 100 99 100 91 BMA0040 conserved hypothetical protein 100 100 100 94 BMA0041 conserved hypothetical protein 100 99 100 95 BMA0042 acyl-CoA dehydrogenase domain protein 100 99 100 96 BMA0043 acyl carrier protein, putative 100 100 100 95 BMA0044 conserved hypothetical protein 100 99 100 96 BMA0045 conserved hypothetical protein 100 100 100 98 BMA0046 -

Microbially Mediated Transformation of Dissolved Nitrogen in Aquatic Environments a Dissertation Submitted to Kent State Univers

Microbially Mediated Transformation of Dissolved Nitrogen in Aquatic Environments A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Xinxin Lu (Lucy) May 2015 © Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published material Dissertation written by Xinxin Lu (Lucy) B.S., Jimei University, 2005 M.S., Ocean University of China, 2008 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2015 Approved by _______________________________________________________________ Xiaozhen Mou, Associate Professor, Ph.D., Department of Biological Sciences _______________________________________________________________ Laura G. Leff, Professor, Ph.D., Department of Biological Sciences _______________________________________________________________ Darren L. Bade, Assistant Professor, Ph.D., Department of Biological Sciences _______________________________________________________________ Joseph D. Ortiz, Professor, Ph.D., Department of Geology _______________________________________________________________ Scott Sheridan, Professor, Ph.D., Department of Geography Accepted by _______________________________________________________________ Laura G. Leff, Professor, Ph.D., Chair, Department of Biological Sciences _______________________________________________________________ James L. Blank, Professor, Ph.D., Dean, College of Arts and Sciences TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS………………………………………………………………………...iii LIST OF FIGURES……………………………………………………………………………....vi LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………………………..xi -

All Enzymes in BRENDA™ the Comprehensive Enzyme Information System

All enzymes in BRENDA™ The Comprehensive Enzyme Information System http://www.brenda-enzymes.org/index.php4?page=information/all_enzymes.php4 1.1.1.1 alcohol dehydrogenase 1.1.1.B1 D-arabitol-phosphate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.2 alcohol dehydrogenase (NADP+) 1.1.1.B3 (S)-specific secondary alcohol dehydrogenase 1.1.1.3 homoserine dehydrogenase 1.1.1.B4 (R)-specific secondary alcohol dehydrogenase 1.1.1.4 (R,R)-butanediol dehydrogenase 1.1.1.5 acetoin dehydrogenase 1.1.1.B5 NADP-retinol dehydrogenase 1.1.1.6 glycerol dehydrogenase 1.1.1.7 propanediol-phosphate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.8 glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (NAD+) 1.1.1.9 D-xylulose reductase 1.1.1.10 L-xylulose reductase 1.1.1.11 D-arabinitol 4-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.12 L-arabinitol 4-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.13 L-arabinitol 2-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.14 L-iditol 2-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.15 D-iditol 2-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.16 galactitol 2-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.17 mannitol-1-phosphate 5-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.18 inositol 2-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.19 glucuronate reductase 1.1.1.20 glucuronolactone reductase 1.1.1.21 aldehyde reductase 1.1.1.22 UDP-glucose 6-dehydrogenase 1.1.1.23 histidinol dehydrogenase 1.1.1.24 quinate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.25 shikimate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.26 glyoxylate reductase 1.1.1.27 L-lactate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.28 D-lactate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.29 glycerate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.30 3-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.31 3-hydroxyisobutyrate dehydrogenase 1.1.1.32 mevaldate reductase 1.1.1.33 mevaldate reductase (NADPH) 1.1.1.34 hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA reductase (NADPH) 1.1.1.35 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2015/0240226A1 Mathur Et Al

US 20150240226A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2015/0240226A1 Mathur et al. (43) Pub. Date: Aug. 27, 2015 (54) NUCLEICACIDS AND PROTEINS AND CI2N 9/16 (2006.01) METHODS FOR MAKING AND USING THEMI CI2N 9/02 (2006.01) CI2N 9/78 (2006.01) (71) Applicant: BP Corporation North America Inc., CI2N 9/12 (2006.01) Naperville, IL (US) CI2N 9/24 (2006.01) CI2O 1/02 (2006.01) (72) Inventors: Eric J. Mathur, San Diego, CA (US); CI2N 9/42 (2006.01) Cathy Chang, San Marcos, CA (US) (52) U.S. Cl. CPC. CI2N 9/88 (2013.01); C12O 1/02 (2013.01); (21) Appl. No.: 14/630,006 CI2O I/04 (2013.01): CI2N 9/80 (2013.01); CI2N 9/241.1 (2013.01); C12N 9/0065 (22) Filed: Feb. 24, 2015 (2013.01); C12N 9/2437 (2013.01); C12N 9/14 Related U.S. Application Data (2013.01); C12N 9/16 (2013.01); C12N 9/0061 (2013.01); C12N 9/78 (2013.01); C12N 9/0071 (62) Division of application No. 13/400,365, filed on Feb. (2013.01); C12N 9/1241 (2013.01): CI2N 20, 2012, now Pat. No. 8,962,800, which is a division 9/2482 (2013.01); C07K 2/00 (2013.01); C12Y of application No. 1 1/817,403, filed on May 7, 2008, 305/01004 (2013.01); C12Y 1 1 1/01016 now Pat. No. 8,119,385, filed as application No. PCT/ (2013.01); C12Y302/01004 (2013.01); C12Y US2006/007642 on Mar. 3, 2006. -

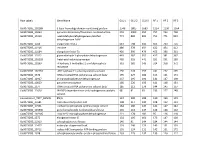

Row Labels Gene Name GLU 1 GLU 2 GLU 3 RF 1 RF 2 RF 3

Row Labels Gene Name GLU 1 GLU 2 GLU 3 RF 1 RF 2 RF 3 Ga0073285_102189 S-layer homology domain-containing protein 1549 1805 1683 1214 1230 1364 Ga0073285_10263 pyruvate-ferredoxin/flavodoxin oxidoreductase 901 1003 950 757 754 738 Ga0073285_14010 acetaldehyde dehydrogenase /alcohol 774 880 805 751 771 823 dehydrogenase AdhE Ga0073285_1166 chaperonin GroEL 663 798 645 563 703 716 Ga0073285_11916 enolase 486 378 459 422 454 412 Ga0073285_11684 elongation factor Tu 426 390 479 453 396 361 Ga0073285_11912 glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase 443 382 352 417 381 367 Ga0073285_101203 ketol-acid reductoisomerase 465 555 441 251 251 280 Ga0073285_10199 4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl diphosphate 361 382 343 314 358 372 reductase Ga0073285_102163 ATP synthase F1 subcomplex beta subunit 256 228 255 241 272 295 Ga0073285_1376 DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit beta' 195 227 186 155 161 171 Ga0073285_12917 D-3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase 237 195 192 142 147 138 Ga0073285_10829 pyruvate carboxylase 185 226 195 141 148 151 Ga0073285_1377 DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit beta 185 212 179 144 145 157 Ga0073285_11620 NAD(P)-dependent iron-only hydrogenase catalytic 98 91 93 233 227 248 subunit Contaminant_TRYP_BOVIN #N/A 157 200 188 130 150 149 Ga0073285_11681 LSU ribosomal protein L4P 198 217 190 108 122 131 Ga0073285_11561 carbamoyl-phosphate synthase large subunit 184 186 149 141 147 142 Ga0073285_101306 polyribonucleotide nucleotidyltransferase 165 164 147 128 146 162 Ga0073285_102105 inosine-5'-monophosphate dehydrogenase 221 178 182 95 116