The Physiology of Pigmented Nevi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Critical Evaluation of the So-Called “Junction Nevus”

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector CRITICAL EVALUATION OF THE SO-CALLED "JUNCTION NEVUS* S. WILLIAM BECKER, MS., M.D. The serious study of pigmented nevi was undertaken by many workers in the closing years of the 19th Century. All recognized that the microscopic picture of nevi differed from anything seen in other organs. The presence of nevus cells in both the epidermis and dermis led to concepts of origin at one or the other site, or at both sites. Dermal Origin: Demieville (1) believed that the nevus cells arose from adven- titial and endothelial cells of blood vessels. Bauer (2) and vonRecklinghausen (3) thought that the origin was from endothelium of lymph vessels rather than of blood vessels. Epidermal Origin: According to Abesser (4), Duranti, in 1871, was the first to suggest an epidermal origin of nevus cells. Kromayer (5) stated that the endo- thelium-like cells originate in the basal portion of the epidermis as "Bläschen- zellen", migrate to the dermis and develop connective tissue and elastic fibers, a change which he called "desmoplasia". Abesser (4) agreed that the cells origi- ated in the epithelium and lost their intercellular bridges, but migrated into the dermis as epithelium-like cells, and remained such. Unna (6) advanced the concept that the epithelial cells changed by losing their intercellular bridges and multiplied in groups, a process which he called "Ab- sonderung", then migrated as groups to the dermis, which he called "Abtrop- fung", thus forming pigmented nevi. -

Atypical Mole Syndrome and Dysplastic Nevi: Identification of Populations at Risk for Developing Melanoma - Review Article

CLINICS 2011;66(3):493-499 DOI:10.1590/S1807-59322011000300023 REVIEW Atypical mole syndrome and dysplastic nevi: identification of populations at risk for developing melanoma - review article Juliana Hypo´ lito Silva,I Bianca Costa Soares de Sa´,II Alexandre Leon Ribeiro de A´ vila,II Gilles Landman,III Joa˜ o Pedreira Duprat NetoII I Oncology School Celestino Bourroul - Hospital AC Camargo, Sa˜ o Paulo, SP, Brazil. II Skin Oncology Department - Hospital AC Camargo - Sa˜ o Paulo, SP, Brazil. III Pathology Department - Hospital AC Camargo - Sa˜ o Paulo, SP, Brazil. Atypical Mole Syndrome is the most important phenotypic risk factor for developing cutaneous melanoma, a malignancy that accounts for about 80% of deaths from skin cancer. Because the diagnosis of melanoma at an early stage is of great prognostic relevance, the identification of Atypical Mole Syndrome carriers is essential, as well as the creation of recommended preventative measures that must be taken by these patients. KEYWORDS: Dysplastic Nevus Syndrome; dysplastic nevi; melanoma; early diagnosis; Risk Factors. Silva JH, de Sa´ BC, Avila ALR, Landman G, Duprat Neto JP. Atypical mole syndrome and dysplastic nevi: identification of populations at risk for developing melanoma - review article. Clinics. 2011;66(3):493-499. Received for publication on November 23, 2010; First review completed on November 24, 2010; Accepted for publication on November 24, 2010 E-mail: [email protected] Tel.: 55 11 2189-5135 INTRODUCTION Several studies have shown that the presence of dysplas- tic nevi considerably increases the risk of developing The incidence of cutaneous melanoma has increased melanoma, which demonstrates that these lesions, aside rapidly worldwide.1-5 Although it corresponds to only 4% of 4 from being precursors to disease are also important risk all skin cancers, it accounts for 80% of skin cancer deaths. -

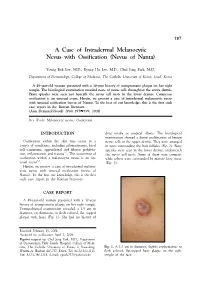

A Case of Intradermal Melanocytic Nevus with Ossification (Nevus of Nanta)

197 A Case of Intradermal Melanocytic Nevus with Ossification (Nevus of Nanta) Young Bok Lee, M.D., Kyung Ho Lee, M.D., Chul Jong Park, M.D. Department of Dermatology, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea A 49-year-old woman presented with a 30-year history of asymptomatic plaque on her right temple. The histological examination revealed nests of nevus cells throughout the entire dermis. Bony spicules were seen just beneath the nevus cell nests in the lower dermis. Cutaneous ossification is an unusual event. Herein, we present a case of intradermal melanocytic nevus with unusual ossification (nevus of Nanta). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first such case report in the Korean literature. (Ann Dermatol (Seoul) 20(4) 197∼199, 2008) Key Words: Melanocytic nevus, Ossification INTRODUCTION drug intake or medical illness. The histological examination showed a dense proliferation of benign Ossification within the skin may occur in a nevus cells in the upper dermis. They were arranged variety of conditions, including pilomatricoma, basal in nests surrounding the hair follicles (Fig. 2). Bony cell carcinoma, appendageal and fibrous prolifera- spicules were seen in the lower dermis, underneath 1,2 tion, inflammation and trauma . The occurrence of the nevus cell nests. Some of them were compact ossification within a melanocytic nevus is an un- while others were surrounded by mature fatty tissue 3-5 usual event . (Fig. 3). Herein, we present a case of intradermal melano- cytic nevus with unusual ossification (nevus of Nanta). To the best our knowledge, this is the first such case report in the Korean literature. -

Short Course 11 Pigmented Lesions of the Skin

Rev Esp Patol 1999; Vol. 32, N~ 3: 447-453 © Prous Science, SA. © Sociedad Espafiola de Anatomfa Patol6gica Short Course 11 © Sociedad Espafiola de Citologia Pigmented lesions of the skin Chairperson F Contreras Spain Ca-chairpersons S McNutt USA and P McKee, USA. Problematic melanocytic nevi melanin pigment is often evident. Frequently, however, the lesion is solely intradermal when it may be confused with a fibrohistiocytic RH. McKee and F.R.C. Path tumor, particularly epithelloid cell fibrous histiocytoma (4). It is typi- cally composed of epitheliold nevus cells with abundant eosinophilic Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, cytoplasm and large, round, to oval vesicular nuclei containing pro- USA. minent eosinophilic nucleoli. Intranuclear cytoplasmic pseudoinclu- sions are common and mitotic figures are occasionally present. The nevus cells which are embedded in a dense, sclerotic connective tis- Whether the diagnosis of any particular nevus is problematic or not sue stroma, usually show maturation with depth. Less frequently the nevus is composed solely of spindle cells which may result in confu- depends upon a variety of factors, including the experience and enthusiasm of the pathologist, the nature of the specimen (shave vs. sion with atrophic fibrous histiocytoma. Desmoplastic nevus can be distinguished from epithelloid fibrous histiocytoma by its paucicellu- punch vs. excisional), the quality of the sections (and their staining), larity, absence of even a focal storiform growth pattern and SiQO pro- the hour of the day or day of the week in addition to the problems relating to the ever-increasing range of histological variants that we tein/HMB 45 expression. -

Digital Epiluminescence Microscopy Monitoring of High-Risk Patients

STUDY Digital Epiluminescence Microscopy Monitoring of High-Risk Patients June K. Robinson, MD; Brian J. Nickoloff, MD, PhD Objective: To examine the outcome of digital epilumi- dence in and comfort with dermatologic surveillance and nescence microscopic (DELM) surveillance of atypical skin self-examination performance were assessed. nevi in a high-risk population for 4 years. Results: During annual surveillance with DELM, 5.5% of Design: Atypical, flat melanocytic lesions in 100 pa- the lesions changed. Among the 193 excisional biopsy speci- tients at high risk of developing melanoma were fol- mens there were 4 melanomas in situ, 169 dysplastic nevi, lowed annually with DELM. Pigmentary changes or an and 20 common nevi. Confidence in and comfort with sur- increase in DELM diameter of 1 mm or greater was an veillance and skin self-examination improved after DELM. indication to perform an excisional biopsy. Conclusions: The criteria applied to detect substantial Setting: Cardinal Bernardin Cancer Center Melanoma DELM changes were an increase in DELM diameter of 1 Program, Loyola University Health System, Maywood. mm or greater and pigmentary changes, including ra- dial streaming, focal enlargement, peripheral black dots, Patients: A consecutive sample of 3482 lesions from 100 and “clumping” within the irregular pigment network. patients (aged 18-65 years) with at least 2 images of the Use of DELM enhanced confidence in and comfort with same lesion. care, which extended to performing more extensive skin self-examination. Main Outcome Measures: -

Oral Pathology

Oral Pathology Palatal blue nevus in a child Catherine M. Flaitz DDS, MS Georgeanne McCandless DDS Dr. Flaitz is professor, Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology and Pediatric Dentistry, Department of Stomatology, University of Texas at Houston Health Science Center Dental Branch; Dr. McCandless has a private practice in The Woodlands, TX. Correspond with Dr. Flaitz at [email protected] Abstract The intraoral blue nevus occurs infrequently in children. This by the labial mucosa (1). Intraoral lesions have a predilection case report describes the clinical features of an acquired blue ne- for females in the third and fourth decades, in contrast to cu- vus in a 7 year-old girl that involved the palatal mucosa. A taneous lesions that normally develop in children. In large differential diagnosis and justification for surgical excision of this biopsy series, only 2% of the oral blue nevi are diagnosed in oral lesion are discussed. (Pediatr Dent 23:354-355, 2001) children and adolescents (1). Similar to their cutaneous coun- terpart, most oral lesions are acquired; however, there are ith the exception of vascular entities, neoplastic isolated reports of congenital examples. lesions with a blue discoloration are an unusual find Clinically, most lesions present as a solitary blue, gray or Wing in children. Although the blue nevus is a blue-black macule or slightly raised nodule that measures less relatively common finding of the skin in the pediatric popula- than 6 mm in size. The margins are often regular but indis- tion, only a few intraoral examples are documented in the tinct and the surface is smooth. -

Identification of HRAS Mutations and Absence of GNAQ Or GNA11

Modern Pathology (2013) 26, 1320–1328 1320 & 2013 USCAP, Inc All rights reserved 0893-3952/13 $32.00 Identification of HRAS mutations and absence of GNAQ or GNA11 mutations in deep penetrating nevi Ryan P Bender1, Matthew J McGinniss2, Paula Esmay1, Elsa F Velazquez3,4 and Julie DR Reimann3,4 1Caris Life Sciences, Phoenix, AZ, USA; 2Genoptix Medical Laboratory, Carlsbad, CA, USA; 3Dermatopathology Division, Miraca Life Sciences Research Institute, Newton, MA, USA and 4Department of Dermatology, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA HRAS is mutated in B15% of Spitz nevi, and GNAQ or GNA11 is mutated in blue nevi (46–83% and B7% respectively). Epithelioid blue nevi and deep penetrating nevi show features of both blue nevi (intradermal location, pigmentation) and Spitz nevi (epithelioid morphology). Epithelioid blue nevi and deep penetrating nevi can also show overlapping features with melanoma, posing a diagnostic challenge. Although epithelioid blue nevi are considered blue nevic variants, no GNAQ or GNA11 mutations have been reported. Classification of deep penetrating nevi as blue nevic variants has also been proposed, however, no GNAQ or GNA11 mutations have been reported and none have been tested for HRAS mutations. To better characterize these tumors, we performed mutational analysis for GNAQ, GNA11, and HRAS, with blue nevi and Spitz nevi as controls. Within deep penetrating nevi, none demonstrated GNAQ or GNA11 mutations (0/38). However, 6% revealed HRAS mutation (2/32). Twenty percent of epithelioid blue nevi contained a GNAQ mutation (2/10), while none displayed GNA11 or HRAS mutation. Eighty-seven percent of blue nevi contained a GNAQ mutation (26/30), 4% a GNA11 mutation (1/28), and none an HRAS mutation. -

Melanomas Are Comprised of Multiple Biologically Distinct Categories

Melanomas are comprised of multiple biologically distinct categories, which differ in cell of origin, age of onset, clinical and histologic presentation, pattern of metastasis, ethnic distribution, causative role of UV radiation, predisposing germ line alterations, mutational processes, and patterns of somatic mutations. Neoplasms are initiated by gain of function mutations in one of several primary oncogenes, typically leading to benign melanocytic nevi with characteristic histologic features. The progression of nevi is restrained by multiple tumor suppressive mechanisms. Secondary genetic alterations override these barriers and promote intermediate or overtly malignant tumors along distinct progression trajectories. The current knowledge about pathogenesis, clinical, histological and genetic features of primary melanocytic neoplasms is reviewed and integrated into a taxonomic framework. THE MOLECULAR PATHOLOGY OF MELANOMA: AN INTEGRATED TAXONOMY OF MELANOCYTIC NEOPLASIA Boris C. Bastian Corresponding Author: Boris C. Bastian, M.D. Ph.D. Gerson & Barbara Bass Bakar Distinguished Professor of Cancer Biology Departments of Dermatology and Pathology University of California, San Francisco UCSF Cardiovascular Research Institute 555 Mission Bay Blvd South Box 3118, Room 252K San Francisco, CA 94158-9001 [email protected] Key words: Genetics Pathogenesis Classification Mutation Nevi Table of Contents Molecular pathogenesis of melanocytic neoplasia .................................................... 1 Classification of melanocytic neoplasms -

A Search for CDKN2A/P16ink4a Mutations in Melanocytic Nevi from Patients with Melanoma and Spouse Controls by Use of Laser-Captured Microdissection

STUDY A Search for CDKN2A/p16INK4a Mutations in Melanocytic Nevi From Patients With Melanoma and Spouse Controls by Use of Laser-Captured Microdissection Hao Wang, MD, PhD; Richard B. Presland, PhD; Michael Piepkorn, MD, PhD Objective: To determine the frequency at which the CDKN2A were observed in any of the melanocytic CDKN2A coding region is mutated in the atypical nevi nevi. of persons with sporadic melanoma. Conclusions: Point mutations in CDKN2A are an un- Design: DNA samples, isolated by laser-captured mi- common event in the atypical nevi of persons with mela- crodissection of atypical nevi from 10 patients with newly noma. As such, the data may support a hypothesis of incident cases of sporadic melanoma and their spouses melanocytic nevus histogenesis, in which the melano- as matched controls, were used as templates for nested cytic nevus and malignant melanoma represent sepa- polymerase chain reaction amplification of CDKN2A rate, pleiotropic pathways resulting from common stimuli, exons 1 and 2. such as genomic damage from UV radiation. Results: No point mutations in the coding region of Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:177-180 ONCEPTUAL MODELS OF messenger RNA are expressed at seem- melanoma development ingly normal levels in atypical as well as ba- and progression incorpo- nal nevi, but at significantly reduced lev- rate common and atypi- els in many melanomas, including the cal (dysplastic) nevi as po- earliest recognizable stage, melanoma in Ctential stages in the evolution of the situ.3-5 Moreover, the phenotype of mul- malignant phenotype in melanocytic sys- tiple and/or enlarged nevi does not geneti- tems.1 Support for this hypothesis can be cally segregate with, nor readily link by found, among other lines of evidence, in the polymorphic markers to, the CDKN2A lo- 6,7 spatial coexistence of melanoma and nevi cus. -

Genomic Copy Number Analysis of a Spectrum of Blue Nevi Identifies

Modern Pathology (2016) 29, 227–239 © 2016 USCAP, Inc All rights reserved 0893-3952/16 $32.00 227 Genomic copy number analysis of a spectrum of blue nevi identifies recurrent aberrations of entire chromosomal arms in melanoma ex blue nevus May P Chan1,2, Aleodor A Andea1,2, Paul W Harms1,2, Alison B Durham2, Rajiv M Patel1,2, Min Wang1, Patrick Robichaud2, Gary J Fisher2, Timothy M Johnson2 and Douglas R Fullen1,2 1Department of Pathology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA and 2Department of Dermatology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA Blue nevi may display significant atypia or undergo malignant transformation. Morphologic diagnosis of this spectrum of lesions is notoriously difficult, and molecular tools are increasingly used to improve diagnostic accuracy. We studied copy number aberrations in a cohort of cellular blue nevi, atypical cellular blue nevi, and melanomas ex blue nevi using Affymetrix’s OncoScan platform. Cases with sufficient DNA were analyzed for GNAQ, GNA11, and HRAS mutations. Copy number aberrations were detected in 0 of 5 (0%) cellular blue nevi, 3 of 12 (25%) atypical cellular blue nevi, and 6 of 9 (67%) melanomas ex blue nevi. None of the atypical cellular blue nevi displayed more than one aberration, whereas complex aberrations involving four or more regions were seen exclusively in melanomas ex blue nevi. Gains and losses of entire chromosomal arms were identified in four of five melanomas ex blue nevi with copy number aberrations. In particular, gains of 1q, 4p, 6p, and 8q, and losses of 1p and 4q were each found in at least two melanomas. -

Nevus of Ota in Children

PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY Series Editor: Camila K. Janniger, MD Nevus of Ota in Children Smeeta Sinha, MD; Philip J. Cohen, MD; Robert A. Schwartz, MD, MPH Nevus of Ota, synonymously termed oculodermal seen most commonly in individuals of Japanese melanosis, is an uncommon dermal melanosis descent, and is less likely to present in individuals most commonly seen at birth in children of of Chinese or Korean descent, though individuals Japanese descent, though it can affect individu- descending from the Indian subcontinent, Africa, als of any age or ethnicity. The disease tends to and Europe also may be affected.7 In early sur- persist and extend locally, becoming increasingly veys of Japanese patients at dermatology clinics, prominent with age, puberty, and postmenopausal the incidence of nevus of Ota was determined to state. Treatment should begin early after diagno- be 0.4% (110/27,500).4 Cowan and Balistocky8 sis using multiple sessions of laser photother- calculated the incidence of oculodermal melano- molysis to avoid darkening and extension of the cytosis in black patients to be 0.016%. A study of lesion. Important associated disorders include 2914 Chinese children in Calgary, Alberta, Canada, ipsilateral glaucoma; intracranial melanocyto- reported an incidence of oculodermal melanocytosis sis; and rarely cutaneous, ocular, or intracranial of 0.034% (1/2914).9 melanoma. Recommendations are discussed for managing nevus of Ota in children. Clinical Manifestation Cutis. 2008;82:25-29. The typical nevus of Ota is a unilateral facial dis- coloration that is macular, speckled, and bluish gray or brown, with edges that blend with bordering skin evus of Ota is a rare disorder characterized (Figure).10 The dermatomal distribution of pigment by melanocytic pigmentation of the sclera characterizes this diagnosis in most cases. -

Blue Nevi and Melanomas Natural Blue BLUE NEVUS Blue Nevus (BN)

KJ Busam, M.D. Paris, 2017 Blue Nevi and Melanomas Natural Blue BLUE NEVUS Blue Nevus (BN) • Spectrum of blue nevi – Common, Sclerosing, Epithelioid, Cellular, Plaque type blue nevi • Differential diagnosis – Melanoma ex BN or simulating BN – BN vs other tumors – Biphenotypic/collision lesions Common Blue Nevus Clinical: - Circumscribed small bluish macule/papule - Preferred sites: Scalp, wrist, foot Pathology: - Predominantly reticular dermal lesion - Pigmented fusiform and dendritic cells - Admixed melanophages - Bland cytology Common Blue Nevus Blue Nevus Sclerosing Blue Nevus Pigm BN Cellular Blue Nevus - 49 yo woman - Buttock nodule CBN Cellular Blue Nevus Thrombi and stromal edema Multinucleated giant melanocytes Cellular Blue Nevus Hemorrhagic cystic (“aneurysmal”) change Amelanotic Cellular Blue Nevus 19 yo man with buttock lesion Atypical CBN Plaque-Type Blue Nevus Plaque-type Blue Nevus Plaque Type Blue Nevus Mucosal Blue Nevus Conjunctival Blue Nevus Nodal Blue Nevus Combined epithelioid BN Blue Nevus • M Tieche 1906; Virchow Arch Pathol Anat “Blaue Naevus” • B Upshaw 1947; Surgery “Extensive Blue Nevus” (plaque-type BN) • A Allen 1949; Cancer “ Cellular Blue Nevus” Blue Nevus – Mutation Analysis Type of Lesion GNAQ GNA11 Number Common BN 6.7% 65% 60 Cellular BN 8.3% 72.2% 36 Amelanotic BN 0% 70% 10 Nevus of Ota 5% 10% 20 Nevus of Ito 16.7% 0% 7 TOTAL 6.5% 55% 139 Van Raamsdonk et al NEJM 2010; 2191-9 Blue Nevus – Mutation Analysis Type of Blue Nevus GNAQ Number Common Blue Nevus 40% 4/10 Cellular Blue Nevus 44% 4/9 Hypomelanotic