The American People and the Centennial of 1876 Walter Nugent*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Relief Programs in the 19Th Century: a Reassessment

The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare Volume 19 Issue 3 September Article 8 September 1992 Federal Relief Programs in the 19th Century: A Reassessment Frank M. Loewenberg Bar-Ilan University, Israel Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jssw Part of the Social History Commons, Social Work Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Loewenberg, Frank M. (1992) "Federal Relief Programs in the 19th Century: A Reassessment," The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare: Vol. 19 : Iss. 3 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jssw/vol19/iss3/8 This Article is brought to you by the Western Michigan University School of Social Work. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Federal Relief Programs in the 19th Century: A Reassessment FRANK M. LOEWENBERG Bar-Ilan University Israel School of Social Work The American model of the welfare state, incomplete as it may be, was not plucked out of thin air by the architects of the New Deal in the 1930s. Instead it is the product and logical evolution of a long histori- cal process. 19th century federal relief programsfor various population groups, including veterans, native Americans, merchant sailors, eman- cipated slaves, and residents of the District of Columbia, are examined in order to help better understand contemporary welfare developments. Many have argued that the federal government was not in- volved in social welfare matters prior to the 1930s - aside from two or three exceptions, such as the establishment of the Freed- man's Bureau in the years after the Civil War and the passage of various federal immigration laws that attempted to stem the flood of immigrants in the 1880s and 1890s. -

Visuality and the Theatre in the Long Nineteenth Century #19Ctheatrevisuality

Visuality and the Theatre in the Long Nineteenth Century #19ctheatrevisuality Henry Emden, City of Coral scene, Drury Lane, pantomime set model, 1903 © V&A Conference at the University of Warwick 27—29 June 2019 Organised as part of the AHRC project, Theatre and Visual Culture in the Long Nineteenth Century, Jim Davis, Kate Holmes, Kate Newey, Patricia Smyth Theatre and Visual Culture in the Long Nineteenth Century Funded by the AHRC, this collaborative research project examines theatre spectacle and spectatorship in the nineteenth century by considering it in relation to the emergence of a wider trans-medial popular visual culture in this period. Responding to audience demand, theatres used sophisticated, innovative technologies to create a range of spectacular effects, from convincing evocations of real places to visions of the fantastical and the supernatural. The project looks at theatrical spectacle in relation to a more general explosion of imagery in this period, which included not only ‘high’ art such as painting, but also new forms such as the illustrated press and optical entertainments like panoramas, dioramas, and magic lantern shows. The range and popularity of these new forms attests to the centrality of visuality in this period. Indeed, scholars have argued that the nineteenth century witnessed a widespread transformation of conceptions of vision and subjectivity. The project draws on these debates to consider how far a popular, commercial form like spectacular theatre can be seen as a site of experimentation and as a crucible for an emergent mode of modern spectatorship. This project brings together Jim Davis and Patricia Smyth from the University of Warwick and Kate Newey and Kate Holmes from the University of Exeter. -

Billy the Kid and the Lincoln County War 1878

Other Forms of Conflict in the West – Billy the Kid and the Lincoln County War 1878 Lesson Objectives: Starter Questions: • To understand how the expansion of 1) We have many examples of how the the West caused other forms of expansion into the West caused conflict with tension between settlers, not just Plains Indians – can you list three examples conflict between white Americans and of conflict and what the cause was in each Plains Indians. case? • To explain the significance of the 2) Can you think of any other groups that may Lincoln County War in understanding have got into conflict with each other as other types of conflict. people expanded west and any reasons why? • To assess the significance of Billy the 3) Why was law and order such a problem in Kid and what his story tells us about new communities being established in the law and order. West? Why was it so hard to stop violence and crime? As homesteaders, hunters, miners and cattle ranchers flooded onto the Plains, they not only came into conflict with the Plains Indians who already lived there, but also with each other. This was a time of robberies, range wars and Indian wars in the wide open spaces of the West. Gradually, the forces of law and order caught up with the lawbreakers, while the US army defeated the Plains Indians. As homesteaders, hunters, miners and cattle ranchers flooded onto the Plains, they not only came into conflict with the Plains Indians who already lived there, but also with each other. -

The Political History of Nineteenth Century Portugal1

The Political History of Nineteenth Century Portugal1 Paulo Jorge Fernandes Autónoma University of Lisbon [email protected] Filipe Ribeiro de Meneses National University of Ireland [email protected] Manuel Baiôa CIDEHUS-University of Évora [email protected] Abstract The political history of nineteenth-century Portugal was, for a long time, a neglected subject. Under Salazar's New State it was passed over in favour of earlier periods from which that nationalist regime sought to draw inspiration; subsequent historians preferred to concentrate on social and economic developments to the detriment of the difficult evolution of Portuguese liberalism. This picture is changing, thanks to an awakening of interest in both contemporary topics and political history (although there is no consensus when it comes to defining political history). The aim of this article is to summarise these recent developments in Portuguese historiography for the benefit of an English-language audience. Keywords Nineteenth Century, History, Bibliography, Constitutionalism, Historiography, Liberalism, Political History, Portugal Politics has finally begun to carve out a privileged space at the heart of Portuguese historiography. This ‘invasion’ is a recent phenomenon and can be explained by the gradual acceptance, over the course of two decades, of political history as a genuine specialisation in Portuguese academic circles. This process of scientific and pedagogical renewal has seen a clear focus also on the nineteenth century. Young researchers concentrate their efforts in this field, and publishers are more interested in this kind of works than before. In Portugal, the interest in the 19th century is a reaction against decades of ignorance. Until April 1974, ideological reasons dictated the absence of contemporary history from the secondary school classroom, and even from the university curriculum. -

1790S 1810S 1820S 1830S 1860S 1870S 1880S 1950S 2000S

Robert Fulton (1765-1815) proposes plans for steam-powered vessels to the 1790s U.S. Government. The first commercial steamboat completes its inaugural journey in 1807 in New York state. Henry Shreve (1785-1851) creates two new types of steamboats: the side-wheeler and the 1810s stern-wheeler. These boats are well suited for the shallow, fast-moving rivers in Arkansas. The first steamboat to arrive in Arkansas, March 31, 1820 Comet, docks at the Arkansas Post. Steamboats traveled the Arkansas, Black, Mississippi, Ouachita, and White Rivers, carrying passengers, raw 1820s materials, consumer goods, and mail to formerly difficult-to-reach communities. Steamboats, or steamers, were used during From the earliest days of the 19th Indian Removal in the1830s for both the shipment 1830s of supplies and passage of emigrants along the century, steamboats played a vital role Arkansas, White, and Ouachita waterways. in the history of Arkansas. Prior to the advent of steamboats, Arkansans were at the mercy of poor roads, high carriage Quatie, wife of Cherokee Chief John Ross, dies aboard Victoria on its way to Indian costs, slow journeys, and isolation. February 1, 1839 Territory and is buried in Little Rock Water routes were the preferred means of travel due to faster travel times and During the Civil War, Arkansas’s rivers offered the only reliable avenue upon which either Confederate or Union fewer hardships. While water travel was 1860s forces could move. Union forces early established control preferable to overland travel, it did not over the rivers in Arkansas. In addition to transporting supplies, some steamers were fitted with armor and come without dangers. -

The Kinney Gang in 1873, 25-Year Old John Kinney Mustered out of the U.S

This is a short biography of outlaw John Kinney, submitted to SCHS by descendant Troy Kelly of Johnson City, NY. John W. Kinney was born in Hampshire, Massachusetts in 1847 (other sources say 1848 or 1853). He and his family moved to Iowas shortly after John was born. On April 13, 1867, Kinney enlisted in the U.S. Army at Chicago, Illinois. On April 13, 1873, at the rank of sergeant, Kinney was mustered out of the U.S. Army at Fort McPherson, Nebraska. Kinney chose not to stay around Nebraska, and he went south to New Mexico Territory. Kinney took up residence in Dona Ana County. He soon became a rustler and the leader of a gang of about thirty rustlers, killers, and thieves. By 1875, the John Kinney Gang was the most feared band of rustler in the territory. They rustled cattle, horses, and mules throughout New Mexico, Arizona, Texas, and Mexico. However, the headquarters for the gang was around the towns of La Mesilla and Las Cruces, both of them located in Dona Ana County. Kinney himself was a very dangerous gunslinger. His apprentice in the gang was Jessie Evants. On New Year's Even in 1875, Kinney, Jessie Evans, and two other John Kinney Gang members name Jim McDaniels and Pony Diehl, got into a bar-room brawl in Las Cruces with some soldiers from nearby Fort Seldon [sic]. The soldiers beat the four rusterls in the fight, and the outlaws were tossed out of the establishment. Kinney himself was severely injured during the fight. Later that night, Kinney, Evans, McDaniels, and Diehl took to the street of Las Cruces and went in front of the saloon they had recently been tossed out of. -

BROTHERS OR ENEMIES the Ukrainian National Movement And

BROTHERS OR ENEMIES The Ukrainian National Movement and Russia, from the 1840s to the 1870s “Moskal.” Mykola Hatchuk, Ukrainska abetka. Moscow: Universytetska dru- karnia, 1861. Courtesy of the National Library of Finland, Slavic collection. JOHANNES REMY Brothers or Enemies The Ukrainian National Movement and Russia, from the 1840s to the 1870s UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS Toronto Buffalo London © University of Toronto Press 2016 Toronto Buffalo London www.utppublishing.com Printed in the U.S.A. ISBN 978-1-4875-0046-7 ♾ Printed on acid-free, 100% post-consumer recycled paper with vegetable-based inks. _________________________________________________________________ Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Remy, Johannes, 1962–, author Brothers or enemies : the Ukrainian national movement and Russia, from the 1840s to the 1870s / Johannes Remy. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4875-0046-7 (cloth) 1. Nationalism – Ukraine – History − 19th century. 2. Ukrainian literature – Censorship – History − 19th century. 3. Imperialism − History − 19th century. 4. Ukraine – History − 19th century. 5. Ukraine − Politics and government − 19th century. 6. Ukraine – Relations − Russia – History − 19th century. 7. Russia – Relations – Ukraine − History − 19th century. I. Title. DK508.772.R44 2016 947.708 C2016-904895-0 _________________________________________________________________ This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences, through the Awards to Scholarly Publica- tions Program, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. The Kowalsky Program for the Study of Eastern Ukraine at Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies has assisted the publication of this book. University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council, an agency of the Government of Ontario. -

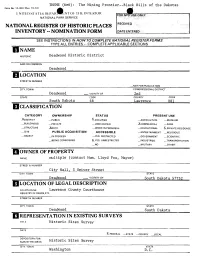

Iowner of Property

THEME (6e6): The Mining Frontier Black Hills of the Dakotas Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) ^^ UNITED STATES DHPARwIiNT OF THH INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY « NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Deadwood Historic District AND/OR COMMON Deadwood LOCATION STREET & NUMBER _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Deadwood _ VICINITY OF 2nd STATE CODE COUNTY CODE South Dakota 46 Lawrence 081 Q CLA SSIFI C ATI ON CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE ^DISTRICT _PUBLIC ^-OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _ BUILDING(S) _PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED -X.COMMERCIAL —PARK _ STRUCTURE _XBOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X_PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS _OBJECT ._IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _BEING CONSIDERED X_YES. UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: IOWNER OF PROPERTY NAME multiple (contact Hon. Lloyd Fox, Mayor) STREEF& NUMBER City Hall, 5 Seiver Street CITY, TOWN STATE Deadwood VICINITY OF South Dakota 57732 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, Lawrence County Courthouse REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Deadwood South Dakota I REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic Sites Survey DATE ^.FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORYSURVEY RECORDS FOR HistoricTT . Sites-, . Survey„ CITY, TOWN STATF. Washington D.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED ^ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD _RUINS XXALTERED MOVED DATF _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Deadwood was a boom town created in 1875 during the Black Hills gold rush. The district is situated in the central area of the town of Deadwood and lies in a steep and narrow valley. -

Chapter 5: Vectors of Settlement

Chapter 5: Vectors of Settlement By the time Mexican soldiers killed Victorio and his followers in the mountains of northern Mexico in October 1880, the Guadalupe Mountains and the trans-Pecos region had already acquired a new sedentary population. An increasing number of Anglo-American and Hispano settlers lived within the boundaries of the Mescalero homeland. To the west, the fertile Mesilla valley had long been a stronghold of Hispano livestock farmers, some of whom grazed animals in the various mountain ranges during the summers; later they explored opportunities to ranch or farm in the region. Finding land expensive and rare along the Rio Grande, still more sought to try their hand at ranching or farming outside the confines of the fertile valley. Others trickled south from Las Vegas, New Mexico, and the Mora area, initially trailing sheep and sometimes a few cows. Some settled along the rivers and streams that passed through the region. Few in the trans-Pecos expected to find wealth in agriculture; only the most savvy, creative, and entrepreneurial stood a chance at achieving such a goal even in the lucrative industry of ranching during its military-supported heyday in the 1860s and 1870s. Other opportunities drew Anglo-Americans to the trans-Pecos. To the north of the Guadalupe Mountains, the two military forts — Stanton and Sumner — became magnets for people who sought to provide the Army with the commodities it needed to feed, clothe, and shelter soldiers and to fill its obligations to reservation Indians. Competition for such contracts provided one of the many smouldering problems that played a part in initiating the Lincoln County War of 1878. -

Review of Seth Bullock: Black Hills Lawman by David A. Wolff Christopher J

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for Spring 2010 Review of Seth Bullock: Black Hills Lawman by David A. Wolff Christopher J. Steinke University of New Mexico Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the American Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, and the United States History Commons Steinke, Christopher J., "Review of Seth Bullock: Black Hills Lawman by David A. Wolff" (2010). Great Plains Quarterly. 2580. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/2580 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Seth Bullock: Black Hills Lawman. By David A. Wolff. Pierre: South Dakota State Historical Society Press, 2009. x + 206 pp. Photographs, notes, bibliography, index. $12.95 paper. In this short biography of Seth Bullock, the first sheriff of Deadwood, South Dakota, 228 GREAT PLAINS QUARTERLY, SUMMER 2010 David A. Wolff challenges a few of the myths of Bullock," but it is not the most rounded surrounding a former frontier icon. Bullock portrait of him, either. Bullock's family life did not in fact "clean up" Deadwood, Wolff is largely missing; his wife Martha receives concludes, nor did he single-handedly prevent only a few paragraphs, even though Wolff skirmishes with nearby Lakotas. His role in makes clear she was actively involved in the establishing Yellowstone National Park was "a Deadwood community, and his children are greatly exaggerated part of his legend." And his scarcely mentioned. -

The Nineteenth-Century Home Theatre: Women and Material Space

The Nineteenth-Century Home Theatre: Women and Material Space Ann Margaret Mazur Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania B.S. Mathematics and English, University of Notre Dame, 2007 M.A. English and American literature, University of Notre Dame, 2009 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English University of Virginia May, 2014 © 2014 Ann M. Mazur Table of Contents Acknowledgments…………...…………………………………………………………..…..……i Dedication…………...……………………………………………………………………………ii Chapter 1 Introduction: The Home Theatre in Context……………………………………...………………1 Chapter 2 A Parlour Education: Reworking Gender and Domestic Space in Ladies’ and Children’s Theatricals...........................63 Chapter 3 Beyond the Home (Drama): Imperialism, Painting, and Adaptation in the Home Theatrical………………………………..126 Chapter 4 Props in Victorian Parlour Plays: the Periperformative, Private Objects, and Restructuring Material Space……………………..206 Chapter 5 Victorian Women, the Home Theatre, and the Cultural Potency of A Doll’s House……….….279 Works Cited………………………………………………………………………………....…325 Acknowledgements I am deeply grateful to the American Association of University Women for my 2013-2014 American Dissertation Fellowship, which provided valuable time as well as the financial means to complete The Nineteenth-Century Home Theatre: Women and Material Space over the past year. I wish to thank my dissertation director Alison Booth, whose support and advice has been tremendous throughout my entire writing process, and who has served as a wonderful mentor during my time as a Ph.D. student at the University of Virginia. My dissertation truly began during an Independent Study on women in the Victorian theatre with Alison during Spring 2011. Karen Chase and John O’Brien, the two supporting members of what I have often called my dream dissertation committee, offered timely encouragement, refreshing insight on chapter drafts, and supported my vision for this genre recovery project. -

Deadwood's Chinatown

Copyright © 1975 by the South Dakota State Historical Society. All Rights Reserved. Deadwood's Chinatown GRANT K. ANDERSON In 1874 General George A. Custer's confirmation that gold existed in Dakota's Black Hills touched off the last great gold rush in the continental United States. The region, once reserved for the SioLix Indians, was quickly overrun by prospectors seeking their fortunes in this newest Eldorado.' The discovery of gold along Whitewood Creek made Deadwood the metropolis of the Black Hills. Almost overnight, it matured from a hastily constructed mining camp to a permanent center of the gold mining industry. During the mining bonanza of the 1870s and 1880s Deadwood boasted more saloons than churches, claimed Wild Bill Hickok and Calamity Jane as residents, and contained the largest Chinatown of any city east of San Francisco. Although largely ignored by historians, the Chinese were among early Deadwood's most colorful inhabitants. The Orientals arrived on the trans-Mississippi West mining frontier during the California gold rush of the 1850s. Their unusual customs and traditions, coupled with their low standard of living, caused them to be looked upon as inferior by the white miners. Unable to understand their economic system or clannish ways, white miners developed a prejudice that 1. Watson Parker, Gold in the Black Hills (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1966), pp. 38-53; Herbert S. ScheU, History of South Dakota (Uncoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1961), pp. 125-30. Copyright © 1975 by the South Dakota State Historical Society. All Rights Reserved. Deadwood's Chinatown 267 excluded Orientals from mining in most gold camps until after the boom period passed.^ This feeling persisted although the number of Chinese was never large—one writer estimates that eight hundred lived in the Montana camps in 1869.^ The patience and industry of the Chinese miners enabled them to make seemingly worthless claims pay.