The Nineteenth-Century Home Theatre: Women and Material Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Relief Programs in the 19Th Century: a Reassessment

The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare Volume 19 Issue 3 September Article 8 September 1992 Federal Relief Programs in the 19th Century: A Reassessment Frank M. Loewenberg Bar-Ilan University, Israel Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jssw Part of the Social History Commons, Social Work Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Loewenberg, Frank M. (1992) "Federal Relief Programs in the 19th Century: A Reassessment," The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare: Vol. 19 : Iss. 3 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jssw/vol19/iss3/8 This Article is brought to you by the Western Michigan University School of Social Work. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Federal Relief Programs in the 19th Century: A Reassessment FRANK M. LOEWENBERG Bar-Ilan University Israel School of Social Work The American model of the welfare state, incomplete as it may be, was not plucked out of thin air by the architects of the New Deal in the 1930s. Instead it is the product and logical evolution of a long histori- cal process. 19th century federal relief programsfor various population groups, including veterans, native Americans, merchant sailors, eman- cipated slaves, and residents of the District of Columbia, are examined in order to help better understand contemporary welfare developments. Many have argued that the federal government was not in- volved in social welfare matters prior to the 1930s - aside from two or three exceptions, such as the establishment of the Freed- man's Bureau in the years after the Civil War and the passage of various federal immigration laws that attempted to stem the flood of immigrants in the 1880s and 1890s. -

“America” on Nineteenth-Century Stages; Or, Jonathan in England and Jonathan at Home

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by D-Scholarship@Pitt PLAYING “AMERICA” ON NINETEENTH-CENTURY STAGES; OR, JONATHAN IN ENGLAND AND JONATHAN AT HOME by Maura L. Jortner BA, Franciscan University, 1993 MA, Xavier University, 1998 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2005 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by It was defended on December 6, 2005 and approved by Heather Nathans, Ph.D., University of Maryland Kathleen George, Ph.D., Theatre Arts Attilio Favorini, Ph.D., Theatre Arts Dissertation Advisor: Bruce McConachie, Ph.D., Theatre Arts ii Copyright © by Maura L. Jortner 2005 iii PLAYING “AMERICA” ON NINETEENTH-CENTURY STAGES; OR, JONATHAN IN ENGLAND AND JONATHAN AT HOME Maura L. Jortner, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2005 This dissertation, prepared towards the completion of a Ph.D. in Theatre and Performance Studies at the University of Pittsburgh, examines “Yankee Theatre” in America and London through a post-colonial lens from 1787 to 1855. Actors under consideration include: Charles Mathews, James Hackett, George Hill, Danforth Marble and Joshua Silsbee. These actors were selected due to their status as iconic performers in “Yankee Theatre.” The Post-Revolutionary period in America was filled with questions of national identity. Much of American culture came directly from England. American citizens read English books, studied English texts in school, and watched English theatre. They were inundated with English culture and unsure of what their own civilization might look like. -

A Bibliographr of the LIFE - AND:DRAMATIC AET OFDIGH BGUGICAULT5

A bibliography of the life and dramatic art of Dion Boucicault; with a handlist of plays Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Livieratos, James Nicholas, 1923- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 29/09/2021 23:28:54 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/318894 A BiBLIOGRAPHr OF THE LIFE - AND:DRAMATIC AET OFDIGH BGUGICAULT5 ■w i t h A M i d l i s t of pla ys v :': . y '- v ■ V; - , ■■ : ■ \.." ■ .' , ' ' „ ; James H 0 Livieratos " ###*##* " A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPART1#!NT OF DRAMA : ^ : Z; In;Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements ... ■ ' For the Degree : qT :.. y , : ^■ . MASTER OF ARTS : •/ : In the Graduate College ■ / UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA ; 1 9 6 0 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfill ment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in The University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable with out special permission, provided that accurate acknowledg ment of source is made. Requests for permission for ex tended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in their judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. -

Visuality and the Theatre in the Long Nineteenth Century #19Ctheatrevisuality

Visuality and the Theatre in the Long Nineteenth Century #19ctheatrevisuality Henry Emden, City of Coral scene, Drury Lane, pantomime set model, 1903 © V&A Conference at the University of Warwick 27—29 June 2019 Organised as part of the AHRC project, Theatre and Visual Culture in the Long Nineteenth Century, Jim Davis, Kate Holmes, Kate Newey, Patricia Smyth Theatre and Visual Culture in the Long Nineteenth Century Funded by the AHRC, this collaborative research project examines theatre spectacle and spectatorship in the nineteenth century by considering it in relation to the emergence of a wider trans-medial popular visual culture in this period. Responding to audience demand, theatres used sophisticated, innovative technologies to create a range of spectacular effects, from convincing evocations of real places to visions of the fantastical and the supernatural. The project looks at theatrical spectacle in relation to a more general explosion of imagery in this period, which included not only ‘high’ art such as painting, but also new forms such as the illustrated press and optical entertainments like panoramas, dioramas, and magic lantern shows. The range and popularity of these new forms attests to the centrality of visuality in this period. Indeed, scholars have argued that the nineteenth century witnessed a widespread transformation of conceptions of vision and subjectivity. The project draws on these debates to consider how far a popular, commercial form like spectacular theatre can be seen as a site of experimentation and as a crucible for an emergent mode of modern spectatorship. This project brings together Jim Davis and Patricia Smyth from the University of Warwick and Kate Newey and Kate Holmes from the University of Exeter. -

Brotherton Library Nineteenth-Century Playbills Handlist of Playbills of the Nineteenth Century Given to the Library by Mrs Blan

Brotherton Library Nineteenth-Century Playbills Handlist of playbills of the nineteenth century given to the Library by Mrs Blanche Legat Leigh (died 194 5) and Professor P.H. Sawyer. The collection is shelved in Special Collections: Theatre: Playbills Contents Pages 1-7: 1-65: Given by Mrs Leigh Pages 8-9: 66-75: Given by Professor Sawyer Pages 10-2 9: Index of Authors, Titles and actors 1 -65: Playbills given by Mrs Leigh 1. 7th Feb. 1806. Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. The Travellers; or, Music's Fascination, by Andrew Cherry (17 62 -1812). Three Weeks after Marriage, by Arthur Murphy (1727-1805), 2. 14th Feb. 1807. Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. The Jealous Wife, by George Colman the elder (1732-94); Tekeli; or, The Siege of Montgatz, by Theodore Edward Hook (17 88-1841). 3. 10th Nov. 1808. Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. The Siege of St. Quintin; or, Spanish Heroism, by T . E. Hook; : The Spoil'd Child, by Isaac Bickerstaffe (173 5-1812), 4. 24th July, 1810. Lyceum Theatre, English Opera. The Duenna, by Richard Brinsley Sheridan (1751- 1816); Twenty Years Ago! by Isaac Pocock (17 82 -183 5). 5. 1st April, 1811. King's Theatre, Haymarket. The Earl of Warwick. .6. 10th Oct. 1812. Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. Hamlet, Prince, of Denmark, by William Shakespeare (1564 -1616); The Devil to Pay; or, The Wives Metamorphosed, by Charles Coffey (d.1745) and John Mottley (1692-1750). 7. 25th May, 1813. Theatre Royal, Covent Garden. The Gameste; by Mrs Susannah Centlivre (1667-1723); The Devil to Pay, by C. Coffey and J. -

Billy the Kid and the Lincoln County War 1878

Other Forms of Conflict in the West – Billy the Kid and the Lincoln County War 1878 Lesson Objectives: Starter Questions: • To understand how the expansion of 1) We have many examples of how the the West caused other forms of expansion into the West caused conflict with tension between settlers, not just Plains Indians – can you list three examples conflict between white Americans and of conflict and what the cause was in each Plains Indians. case? • To explain the significance of the 2) Can you think of any other groups that may Lincoln County War in understanding have got into conflict with each other as other types of conflict. people expanded west and any reasons why? • To assess the significance of Billy the 3) Why was law and order such a problem in Kid and what his story tells us about new communities being established in the law and order. West? Why was it so hard to stop violence and crime? As homesteaders, hunters, miners and cattle ranchers flooded onto the Plains, they not only came into conflict with the Plains Indians who already lived there, but also with each other. This was a time of robberies, range wars and Indian wars in the wide open spaces of the West. Gradually, the forces of law and order caught up with the lawbreakers, while the US army defeated the Plains Indians. As homesteaders, hunters, miners and cattle ranchers flooded onto the Plains, they not only came into conflict with the Plains Indians who already lived there, but also with each other. -

FRENCH INFLUENCES on ENGLISH RESTORATION THEATRE a Thesis

FRENCH INFLUENCES ON ENGLISH RESTORATION THEATRE A thesis submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University In partial fulfillment of A the requirements for the Degree 2oK A A Master of Arts * In Drama by Anne Melissa Potter San Francisco, California Spring 2016 Copyright by Anne Melissa Potter 2016 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read French Influences on English Restoration Theatre by Anne Melissa Potter, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master of Arts: Drama at San Francisco State University. Bruce Avery, Ph.D. < —•— Professor of Drama "'"-J FRENCH INFLUENCES ON RESTORATION THEATRE Anne Melissa Potter San Francisco, California 2016 This project will examine a small group of Restoration plays based on French sources. It will examine how and why the English plays differ from their French sources. This project will pay special attention to the role that women played in the development of the Restoration theatre both as playwrights and actresses. It will also examine to what extent French influences were instrumental in how women develop English drama. I certify that the abstract rrect representation of the content of this thesis PREFACE In this thesis all of the translations are my own and are located in the footnote preceding the reference. I have cited plays in the way that is most helpful as regards each play. In plays for which I have act, scene and line numbers I have cited them, using that information. For example: I.ii.241-244. -

Harvey Study Guide

STUDY GUIDE SHOW SYNOPSIS HARVEY, the classic Pulitzer Prize-winning Broadway and Hollywood comedy, pulls laughter out of the hat at every turn. Elwood P. Dowd is charming and kind with one character flaw: an unwa- vering friendship with a 6-foot-tall, invisible white rabbit named Harvey. When Elwood starts to introduce his friend to guests at a society party, his sister Veta can't take it anymore. In order to save the family's social reputation, Elwood's sister takes him to the local sanatorium. But when the doctor mistakenly commits his anxiety-ridden sister, Elwood and Harvey slip out of the hospital unbothered, setting off a hilarious whirlwind of confusion and chaos as everyone in town tries to catch a man and his invisible rabbit. DISCUSSION QUESTIONS BEFORE THE SHOW AFTER THE SHOW Has anyone ever been to a live play before? How was Did you enjoy this performance? What was your it different from television or a movie? favorite part? What is the difference between a play and a musical? Who was your favorite character? Why? Why do you think some of the characters, Have you ever seen the movie Harvey? particularly Elwood, can see Harvey and others Did you have an imaginary friend as a young kid? can’t? What do you remember about them? Do you think Veta made the right decision in not allowing her brother to receive the medicine? Why Could you imagine still having an imaginary friend or why not? as an adult? How do you think others would respond Do you think Harvey is imaginary? Why or why to you in this situation? not? THEATRE 101 Ever wondered how to put on a play? ACTORS The actors are the people that perform the show There are many different elements that go into putting a show onstage. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

TV & Radio Script

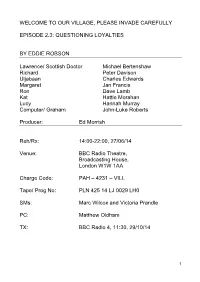

WELCOME TO OUR VILLAGE, PLEASE INVADE CAREFULLY EPISODE 2.3: QUESTIONING LOYALTIES BY EDDIE ROBSON Lawrence/ Scottish Doctor Michael Bertenshaw Richard Peter Davison Uljabaan Charles Edwards Margaret Jan Francis Ron Dave Lamb Kat Hattie Morahan Lucy Hannah Murray Computer / Graham John-Luke Roberts Producer: Ed Morrish Reh/Rx: 14:00-22:00, 27/06/14 Venue: BBC Radio Theatre, Broadcasting House, London W1W 1AA Charge Code: PAH – 4231 – VILL Tape/ Prog No: PLN 425 14 LJ 0029 LH0 SMs: Marc Wilcox and Victoria Prandle PC: Matthew Oldham TX: BBC Radio 4, 11:30, 29/10/14 1 1 GRAMS SWARM OF EVIL (UNDER) 2 INTRO: Welcome To Our Village, Please Invade Carefully, by Eddie Robson. Episode three: Questioning Loyalties. 3 GRAMS OUT 2 SCENE 1 EXT. PARK 1 F/X: LAWRENCE, THE PARK KEEPER (40s), JANGLES HIS KEYS AS HE PREPARES TO UNLOCK A SHED. 2 KATRINA: Lawrence! Don’t open that shed! 3 LAWRENCE: Hello Katrina. How’s your mum and dad? 4 KATRINA: Normal. Just like everything else. Completely normal. 5 LAWRENCE: Must be a bit funny, living with them again, staying in your old bedroom, now you’re 34! 6 KATRINA: Yes, it’s hilarious. In fact it’s one of the most amusing things about being trapped in a village that’s been invaded by aliens and cut off from the outside world. 7 LAWRENCE: Isn’t it strange how life turns out. 8 KATRINA: It’s stranger than I expected, I’ll grant you that. 9 LAWRENCE: I need to get on and mow this grass, so if you could just let me get into the shed – 10 KATRINA: Don’t look in the shed! 11 LAWRENCE: Why not? 3 1 KATRINA: Take a break. -

ONWARD and UPWARD Opportunity Comes in Many Forms and Two Colors, Blue and Gold

NURSING’S ACCESS WEATHERSPOON’S NANCY ADAMS, P.2 FOR VETERANS P. 24 BIG BANG P. 28 AHEAD OF HER TIME FOR ALUMNI AND FRIENDS SPRING 2016 Volume 17, No. 2 MAGAZINE ONWARD AND UPWARD Opportunity comes in many forms and two colors, blue and gold. PG. 12 SHOW AND TELL Students in Professor Jo Leimenstoll’s interior architecture class had the opportunity to do prospective design work for a historic downtown building. Best of all, they had the chance to speak with and learn from developers, city officials and consultants 12 such as alumna Megan Sullivan (far right in picture) as they presented their creative work. UNCG’s undergraduate program was rated No. 4 nationally in a DesignIntelligence Magazine survey of deans and department heads. See more opportunity-themed stories and photos in the Golden Opportunity feature. PHOTOGRAPHY BY MARTIN W. KANE. KANE. PHOTOGRAPHY BY MARTIN W. contents news front 2 University and alumni news and notes out take 8 Purple reigns in Peabody Park the studio 10 Arts and entertainment 12 Golden Opportunity UNCG provides the chance to strive for dreams and prepare to make your mark on the world. Some alumni and students share their tales of transformation. Weatherspoon’s Big Bang 24 Gregory Ivy arrived to create an art department, and ultimately de Kooning’s “Woman” was purchased as part of the Weatherspoon collection. Ahead of Her Time 28 Nancy Adams ’60, ’77 MS didn’t set out to be a pioneer. But with Dean Eberhart’s help, she became North Carolina’s first genetic counselor. -

"Woman.Life.Song" by Judith Weir Heather Drummon Cawlfield

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Dissertations Student Research 5-1-2015 Study and analysis of "woman.life.song" by Judith Weir Heather Drummon Cawlfield Follow this and additional works at: http://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Cawlfield, Heather Drummon, "Study and analysis of "woman.life.song" by Judith Weir" (2015). Dissertations. Paper 14. This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © 2015 HEATHER DRUMMOND CAWLFIELD ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School STUDY AND ANALYSIS OF woman.life.song BY JUDITH WEIR A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Arts Heather Drummond Cawlfield College of Performing and Visual Arts School of Music Music Performance May 2015 This Dissertation by: Heather Drummond Cawlfield Entitled: Study and Analysis of “woman.life.song” by Judith Weir has been approved as meeting the requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Arts in College of Performing Arts in School of Music, Program of Vocal Performance Accepted by the Doctoral Committee ______________________________________________________ Melissa Malde, D.M.A., Research Advisor ______________________________________________________ Brian Luedloff, M.F.A., Co-Research Advisor (if applicable) _______________________________________________________ Robert Ehle, Ph.D., Committee Member _______________________________________________________ Susan Collins, Ph.D., Committee Member Date of Dissertation Defense _________________________________________ Accepted by the Graduate School _________________________________________________________ Linda L. Black, Ed.D.