Chapter 5: Vectors of Settlement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3Rd Quarter 2017

Stagecoach Property Owners Association Stagecoach Express A Quarterly Newsletter www.Stage-Coach.com № 3rd Quarter • 2017 President’s Message Meet the Association’s New Membership Survey 2017 Property Valuations Stagecoach Real Estate Board Members on Potential Covenant Activity Amendments Page 1-2 Page 2 Page 3-4 Page 5 Page 6 Out with the old, in with the Wildfire Mitigation - Now Common Area Trail Construction Board Meeting Minutes new... you see it, now you don’t... Improvements... Continues... May 13, 2017 Page 7 Page 8 Page 9 Page 10 Page 13-19 Board Meeting Minutes July 1, 2017 Page 20-26 While there are still many unknowns, this is a critical issue for all members of the Association. The Board and the President’s Association’s legal counsel are closely monitoring events and communications on this issue and we have been in contact Message with the State, County and district officials regarding our concerns. By John Troka You can find more information about this issue on our website at www.Stage-coach.com. We will also post additional information and updates on the website as appropriate. I As fall begins in Stagecoach, we look forward to the encourage each of you to actively engage in understanding changing colors and cooler, and hopefully, wetter days ahead. and participate with the Association in seeking a positive Unfortunately this year the change in seasons may also bring resolution of this matter with it a significant challenge for our members whose lots are In other Association news, the Association’s annual not currently served by the centralized water and sanitation membership meeting was held in July. -

Federal Relief Programs in the 19Th Century: a Reassessment

The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare Volume 19 Issue 3 September Article 8 September 1992 Federal Relief Programs in the 19th Century: A Reassessment Frank M. Loewenberg Bar-Ilan University, Israel Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jssw Part of the Social History Commons, Social Work Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Loewenberg, Frank M. (1992) "Federal Relief Programs in the 19th Century: A Reassessment," The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare: Vol. 19 : Iss. 3 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jssw/vol19/iss3/8 This Article is brought to you by the Western Michigan University School of Social Work. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Federal Relief Programs in the 19th Century: A Reassessment FRANK M. LOEWENBERG Bar-Ilan University Israel School of Social Work The American model of the welfare state, incomplete as it may be, was not plucked out of thin air by the architects of the New Deal in the 1930s. Instead it is the product and logical evolution of a long histori- cal process. 19th century federal relief programsfor various population groups, including veterans, native Americans, merchant sailors, eman- cipated slaves, and residents of the District of Columbia, are examined in order to help better understand contemporary welfare developments. Many have argued that the federal government was not in- volved in social welfare matters prior to the 1930s - aside from two or three exceptions, such as the establishment of the Freed- man's Bureau in the years after the Civil War and the passage of various federal immigration laws that attempted to stem the flood of immigrants in the 1880s and 1890s. -

Dangerously Free: Outlaws and Nation-Making in Literature of the Indian Territory

DANGEROUSLY FREE: OUTLAWS AND NATION-MAKING IN LITERATURE OF THE INDIAN TERRITORY by Jenna Hunnef A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of English University of Toronto © Copyright by Jenna Hunnef 2016 Dangerously Free: Outlaws and Nation-Making in Literature of the Indian Territory Jenna Hunnef Doctor of Philosophy Department of English University of Toronto 2016 Abstract In this dissertation, I examine how literary representations of outlaws and outlawry have contributed to the shaping of national identity in the United States. I analyze a series of texts set in the former Indian Territory (now part of the state of Oklahoma) for traces of what I call “outlaw rhetorics,” that is, the political expression in literature of marginalized realities and competing visions of nationhood. Outlaw rhetorics elicit new ways to think the nation differently—to imagine the nation otherwise; as such, I demonstrate that outlaw narratives are as capable of challenging the nation’s claims to territorial or imaginative title as they are of asserting them. Borrowing from Abenaki scholar Lisa Brooks’s definition of “nation” as “the multifaceted, lived experience of families who gather in particular places,” this dissertation draws an analogous relationship between outlaws and domestic spaces wherein they are both considered simultaneously exempt from and constitutive of civic life. In the same way that the outlaw’s alternately celebrated and marginal status endows him or her with the power to support and eschew the stories a nation tells about itself, so the liminality and centrality of domestic life have proven effective as a means of consolidating and dissenting from the status quo of the nation-state. -

Three Library Speakers Series

THREE LIBRARY SPEAKERS SERIES ARDEN-DIMICK LIBRARY SPEAKERS SERIES OFF CAMPUS, DROP-IN, NO REGISTRATION REQUIRED All programs are on Mondays, 10:00 a.m. to 11:30 a.m. Because the location is a public library, the meetings are open to the public. 891 Watt Avenue, Sacramento 95864 NOTE: Community Room doors on north side open at 9:45 a.m. Leader: Carolyn Martin, [email protected] March 9 How Women Finally Got the Right to Vote – Carolyn Martin The frequently frustrating suffrage struggle celebrated the California victory in 1911. It was an innovative and invigorating campaign. Learn about our State’s leadership, the movement’s background and ultimately national victory in 1920. March 16 Sacramento’s Hidden Art Deco Treasures – Bruce Marwick The Preservation Chair of the Sacramento Art Deco Society will share images of buildings, paintings and sculptures that typify the beautiful art deco period. Sacramento boasts a high concentration of WPA (Works Progress Administration) 1930s projects. His special interest, murals by artists Maynard Dixon, Ralph Stackpole and Millard Sheets will be featured. March 23 Origins of Western Universities – Ed Sherman Along with libraries and museums, our universities act as memory for Western Civilization. How did this happen? March 30 The Politics of Food and Drink – Steve and Susie Swatt Historic watering holes and restaurants played important roles in the temperance movement, suffrage, and the outrageous shenanigans of characters such as Art Samish, the powerful lobbyist for the alcoholic beverage industry. New regulations have changed both the drinking scene and Capitol politics. April 6 Communication Technology and Cultural Change - Phil Lane Searching for better communication has evolved from written language to current technological developments. -

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

Mining Kit Teacher Manual Contents

Mining Kit Teacher Manual Contents Exploring the Kit: Description and Instructions for Use……………………...page 2 A Brief History of Mining in Colorado ………………………………………page 3 Artifact Photos and Descriptions……………………………………………..page 5 Did You Know That…? Information Cards ………………………………..page 10 Ready, Set, Go! Activity Cards ……………………………………………..page 12 Flash! Photograph Packet…………………………………………………...page 17 Eureka! Instructions and Supplies for Board Game………………………...page 18 Stories and Songs: Colorado’s Mining Frontier ………………………………page 24 Additional Resources…………………………………………………………page 35 Exploring the Kit Help your students explore the artifacts, information, and activities packed inside this kit, and together you will dig into some very exciting history! This kit is for students of all ages, but it is designed to be of most interest to kids from fourth through eighth grades, the years that Colorado history is most often taught. Younger children may require more help and guidance with some of the components of the kit, but there is something here for everyone. Case Components 1. Teacher’s Manual - This guidebook contains information about each part of the kit. You will also find supplemental materials, including an overview of Colorado’s mining history, a list of the songs and stories on the cassette tape, a photograph and thorough description of all the artifacts, board game instructions, and bibliographies for teachers and students. 2. Artifacts – You will discover a set of intriguing artifacts related to Colorado mining inside the kit. 3. Information Cards – The information cards in the packet, Did You Know That…? are written to spark the varied interests of students. They cover a broad range of topics, from everyday life in mining towns, to the environment, to the impact of mining on the Ute Indians, and more. -

Re-Imagining Indians: the Counter-Hegemonic Represenations of Victor Masayesva and Chris Eyre

Re-Imagining Indians: The Counter-Hegemonic Represenations of Victor Masayesva and Chris Eyre Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Cassadore, Edison Duane Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 02/10/2021 09:39:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/195409 RE-IMAGINING INDIANS: THE COUNTER-HEGEMONIC REPRESENTATIONS OF VICTOR MASAYESVA AND CHRIS EYRE by Edison Duane Cassadore _______________________ Copyright © Edison Duane Cassadore 2007 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF COMPARATIVE CULTURAL AND LITERARY STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 7 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Edison Cassadore entitled Re-Imagining Indians: The Counter-Hegemonic Representations of Victor Masayesva and Chris Eyre and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________________________________________________________________ Date: September 23, 2005 Barbara Babcock _______________________________________________________________________ -

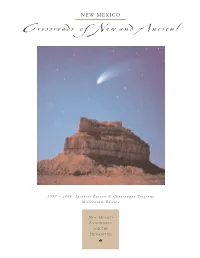

Crossroads of Newand Ancient

NEW MEXICO Crossroads of NewandAncient 1999 – 2000 Speakers Bureau & Chautauqua Programs Millennium Edition N EW M EXICO E NDOWMENT FOR THE H UMANITIES ABOUT THE COVER: AMATEUR PHOTOGRAPHER MARKO KECMAN of Aztec captures the crossroads of ancient and modern in New Mexico with this image of Comet Hale-Bopp over Fajada Butte in Chaco Culture National Historic Park. Kecman wanted to juxtapose the new comet with the butte that was an astronomical observatory in the years 900 – 1200 AD. Fajada (banded) Butte is home to the ancestral Puebloan sun shrine popularly known as “The Sun Dagger” site. The butte is closed to visitors to protect its fragile cultural sites. The clear skies over the Southwest led to discovery of Hale-Bopp on July 22-23, 1995. Alan Hale saw the comet from his driveway in Cloudcroft, New Mexico, and Thomas Bopp saw the comet from the desert near Stanfield, Arizona at about the same time. Marko Kecman: 115 N. Mesa Verde Ave., Aztec, NM, 87410, 505-334-2523 Alan Hale: Southwest Institute for Space Research, 15 E. Spur Rd., Cloudcroft, NM 88317, 505-687-2075 1999-2000 NEW MEXICO ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES SPEAKERS BUREAU & CHAUTAUQUA PROGRAMS Welcome to the Millennium Edition of the New Mexico Endowment for the Humanities (NMEH) Resource Center Programming Guide. This 1999-2000 edition presents 52 New Mexicans who deliver fascinating programs on New Mexico, Southwest, national and international topics. Making their debuts on the state stage are 16 new “living history” Chautauqua characters, ranging from an 1840s mountain man to Martha Washington, from Governor Lew Wallace to Capitán Rafael Chacón, from Pat Garrett to Harry Houdini and Kit Carson to Mabel Dodge Luhan. -

Visuality and the Theatre in the Long Nineteenth Century #19Ctheatrevisuality

Visuality and the Theatre in the Long Nineteenth Century #19ctheatrevisuality Henry Emden, City of Coral scene, Drury Lane, pantomime set model, 1903 © V&A Conference at the University of Warwick 27—29 June 2019 Organised as part of the AHRC project, Theatre and Visual Culture in the Long Nineteenth Century, Jim Davis, Kate Holmes, Kate Newey, Patricia Smyth Theatre and Visual Culture in the Long Nineteenth Century Funded by the AHRC, this collaborative research project examines theatre spectacle and spectatorship in the nineteenth century by considering it in relation to the emergence of a wider trans-medial popular visual culture in this period. Responding to audience demand, theatres used sophisticated, innovative technologies to create a range of spectacular effects, from convincing evocations of real places to visions of the fantastical and the supernatural. The project looks at theatrical spectacle in relation to a more general explosion of imagery in this period, which included not only ‘high’ art such as painting, but also new forms such as the illustrated press and optical entertainments like panoramas, dioramas, and magic lantern shows. The range and popularity of these new forms attests to the centrality of visuality in this period. Indeed, scholars have argued that the nineteenth century witnessed a widespread transformation of conceptions of vision and subjectivity. The project draws on these debates to consider how far a popular, commercial form like spectacular theatre can be seen as a site of experimentation and as a crucible for an emergent mode of modern spectatorship. This project brings together Jim Davis and Patricia Smyth from the University of Warwick and Kate Newey and Kate Holmes from the University of Exeter. -

Interview No. 282

University of Texas at El Paso ScholarWorks@UTEP Combined Interviews Institute of Oral History 12-1976 Interview no. 282 George E. Barnhart Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.utep.edu/interviews Part of the Oral History Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Interview with George E. Barnhart by Carlos Tapia, 1976, "Interview no. 282," Institute of Oral History, University of Texas at El Paso. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute of Oral History at ScholarWorks@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Combined Interviews by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITYOFTEXAS AT EL PASC INSTITUTEOFOR.AL HISTORY II.ITERVIEIdEE: GeorqeE. Barnhart INTERVIEI.IER: CarlosTaPia PROJECT: Class proiect DATEOF II'ITERVIEI'I: DecemberI 976 TERI''6OF USE: Unrestricted TAPENO.: 282 T:IAI'ISCRIPTI.iO.: 282 TRAIISCRISER: DATETRA|'ISCRIBED: BIOGRAPHICALSYiiOPSIS OF INTERVIEI'IEE: 01d-time E] Pasoresident. SUI{I}trRYOF I|'ITER\IIEI,I: j I ett and BioqraPhy;the MexicanRevol ution; Prohbi tion ; J'imGi JudgeRoy Bean' John|.lesleY Hardin; tf," O.pt.ssion; Worldl'lar II; 50 minutes I4 pages 'interview { Oral History with Mr- GeorgeE. Barnhart, interviewedby Carlos Tapia in December1976" ) T: Mr. Barnhar{wherewere you born and when? B: hlestBends, Okl ahoma. T: Whatwas the date? B: We]l, it's supposedto be February24, 1896. Theydidn't keepany records back in themdays. I had to checkback and I got two or three different [dates, but] that's the one I usedto look for a job. -

Gold Fever! Seattle Outfits the Klondike Gold Rush. Teaching with Historic Places

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 442 682 SO 031 322 AUTHOR Blackburn, Marc K. TITLE Gold Fever! Seattle Outfits the Klondike Gold Rush. Teaching with Historic Places. INSTITUTION National Register of Historic Places, Washington, DC. Interagency Resources Div. PUB DATE 1999-00-00 NOTE 28p. AVAILABLE FROM Teaching with Historic Places, National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service, 1849 C Street, NW, Suite NC400, Washington, DC 20240. For full text: http://www.cr.nps.gov/nr/twhp/wwwlps/lessons/55klondike/55 Klondike.htm PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Foreign Countries; Historic Sites; *Local History; Primary Sources; Secondary Education; Social Studies; *United States History; *Urban Areas; *Urban Culture IDENTIFIERS Canada; *Klondike Gold Rush; National Register of Historic Places; *Washington (Seattle); Westward Movement (United States) ABSTRACT This lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places registration file, "Pioneer Square Historic District," and other sources about Seattle (Washington) and the Klondike Gold Rush. The lesson helps students understand how Seattle exemplified the prosperity of the Klondike Gold Rush after 1897 when news of a gold strike in Canada's Yukon Valley reached Seattle and the city's face was changed dramatically by furious commercial activity. The lesson can be used in units on western expansion, late 19th-century commerce, and urban history. It is divided into the following sections: "About This Lesson"; "Setting the Stage: Historical -

In the Shadow of Billy the Kid: Susan Mcsween and the Lincoln County War Author(S): Kathleen P

In the Shadow of Billy the Kid: Susan McSween and the Lincoln County War Author(s): Kathleen P. Chamberlain Source: Montana: The Magazine of Western History, Vol. 55, No. 4 (Winter, 2005), pp. 36-53 Published by: Montana Historical Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4520742 . Accessed: 31/01/2014 13:20 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Montana Historical Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Montana: The Magazine of Western History. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 142.25.33.193 on Fri, 31 Jan 2014 13:20:15 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions In the Shadowof Billy the Kid SUSAN MCSWEEN AND THE LINCOLN COUNTY WAR by Kathleen P. Chamberlain S C.4 C-5 I t Ia;i - /.0 I _Lf Susan McSween survivedthe shootouts of the Lincoln CountyWar and createda fortunein its aftermath.Through her story,we can examinethe strugglefor economic control that gripped Gilded Age New Mexico and discoverhow women were forced to alter their behavior,make decisions, and measuresuccess againstthe cold realitiesof the period. This content downloaded from 142.25.33.193 on Fri, 31 Jan 2014 13:20:15 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions ,a- -P N1878 southeastern New Mexico declared war on itself.