Download Vol. 22, No. 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dominican Republic Endemics of Hispaniola II 1St February to 9Th February 2021 (9 Days)

Dominican Republic Endemics of Hispaniola II 1st February to 9th February 2021 (9 days) Palmchat by Adam Riley Although the Dominican Republic is perhaps best known for its luxurious beaches, outstanding food and vibrant culture, this island has much to offer both the avid birder and general naturalist alike. Because of the amazing biodiversity sustained on the island, Hispaniola ranks highest in the world as a priority for bird protection! This 8-day birding tour provides the perfect opportunity to encounter nearly all of the island’s 32 endemic bird species, plus other Greater Antillean specialities. We accomplish this by thoroughly exploring the island’s variety of habitats, from the evergreen and Pine forests of the Sierra de Bahoruco to the dry forests of the coast. Furthermore, our accommodation ranges from remote cabins deep in the forest to well-appointed hotels on the beach, each with its own unique local flair. Join us for this delightful tour to the most diverse island in the Caribbean! RBL Dominican Republic Itinerary 2 THE TOUR AT A GLANCE… THE ITINERARY Day 1 Arrival in Santo Domingo Day 2 Santo Domingo Botanical Gardens to Sabana del Mar (Paraiso Caño Hondo) Day 3 Paraiso Caño Hondo to Santo Domingo Day 4 Salinas de Bani to Pedernales Day 5 Cabo Rojo & Southern Sierra de Bahoruco Day 6 Cachote to Villa Barrancoli Day 7 Northern Sierra de Bahoruco Day 8 La Placa, Laguna Rincon to Santo Domingo Day 9 International Departures TOUR ROUTE MAP… RBL Dominican Republic Itinerary 3 THE TOUR IN DETAIL… Day 1: Arrival in Santo Domingo. -

The Journal of Caribbean Ornithology

THE J OURNAL OF CARIBBEAN ORNITHOLOGY SOCIETY FOR THE C ONSERVATION AND S TUDY OF C ARIBBEAN B IRDS S OCIEDAD PARA LA C ONSERVACIÓN Y E STUDIO DE LAS A VES C ARIBEÑAS ASSOCIATION POUR LA C ONSERVATION ET L’ E TUDE DES O ISEAUX DE LA C ARAÏBE 2005 Vol. 18, No. 1 (ISSN 1527-7151) Formerly EL P ITIRRE CONTENTS RECUPERACIÓN DE A VES M IGRATORIAS N EÁRTICAS DEL O RDEN A NSERIFORMES EN C UBA . Pedro Blanco y Bárbara Sánchez ………………....................................................................................................................................................... 1 INVENTARIO DE LA A VIFAUNA DE T OPES DE C OLLANTES , S ANCTI S PÍRITUS , C UBA . Bárbara Sánchez ……..................... 7 NUEVO R EGISTRO Y C OMENTARIOS A DICIONALES S OBRE LA A VOCETA ( RECURVIROSTRA AMERICANA ) EN C UBA . Omar Labrada, Pedro Blanco, Elizabet S. Delgado, y Jarreton P. Rivero............................................................................... 13 AVES DE C AYO C ARENAS , C IÉNAGA DE B IRAMA , C UBA . Omar Labrada y Gabriel Cisneros ……………........................ 16 FORAGING B EHAVIOR OF T WO T YRANT F LYCATCHERS IN T RINIDAD : THE G REAT K ISKADEE ( PITANGUS SULPHURATUS ) AND T ROPICAL K INGBIRD ( TYRANNUS MELANCHOLICUS ). Nadira Mathura, Shawn O´Garro, Diane Thompson, Floyd E. Hayes, and Urmila S. Nandy........................................................................................................................................ 18 APPARENT N ESTING OF S OUTHERN L APWING ON A RUBA . Steven G. Mlodinow................................................................ -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

The Relationships of the Starlings (Sturnidae: Sturnini) and the Mockingbirds (Sturnidae: Mimini)

THE RELATIONSHIPS OF THE STARLINGS (STURNIDAE: STURNINI) AND THE MOCKINGBIRDS (STURNIDAE: MIMINI) CHARLESG. SIBLEYAND JON E. AHLQUIST Departmentof Biologyand PeabodyMuseum of Natural History,Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06511 USA ABSTRACT.--OldWorld starlingshave been thought to be related to crowsand their allies, to weaverbirds, or to New World troupials. New World mockingbirdsand thrashershave usually been placed near the thrushesand/or wrens. DNA-DNA hybridization data indi- cated that starlingsand mockingbirdsare more closelyrelated to each other than either is to any other living taxon. Some avian systematistsdoubted this conclusion.Therefore, a more extensiveDNA hybridizationstudy was conducted,and a successfulsearch was made for other evidence of the relationshipbetween starlingsand mockingbirds.The resultssup- port our original conclusionthat the two groupsdiverged from a commonancestor in the late Oligoceneor early Miocene, about 23-28 million yearsago, and that their relationship may be expressedin our passerineclassification, based on DNA comparisons,by placing them as sistertribes in the Family Sturnidae,Superfamily Turdoidea, Parvorder Muscicapae, Suborder Passeres.Their next nearest relatives are the members of the Turdidae, including the typical thrushes,erithacine chats,and muscicapineflycatchers. Received 15 March 1983, acceptedI November1983. STARLINGS are confined to the Old World, dine thrushesinclude Turdus,Catharus, Hylocich- mockingbirdsand thrashersto the New World. la, Zootheraand Myadestes.d) Cinclusis -

The Journal of the Geological Society of Jamaica Bauxite /Alumina Symposium 1971

I THE JOURNAL OF THE GEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF JAMAICA BAUXITE /ALUMINA SYMPOSIUM 1971 LIBRARY 01' ISSUE '/// <°* PREFACE The recent Bauxite/Alumina Industry Symposium, which was sponsored by the Geo logical Society of Jamaica, was an attempt to bring together scientists and engineers to discuss the many problems relating to the industry. Ihe use of a multi-dicipli- nary approach has the advantage of permitting different lines of attack on the same problems, and thereby increasing the likelihood of finding solutions to them. Also, the interaction of people from the University, industry and Government greatly facilitates communication and allows problems to be evaluated and examined from different points of view. The bauxite/alumina industry was selected for discussion because of its significance in the economy of Jamaica. It contributed about 16% of the country's total Gross Domestic Product in 1970, and is the economic sector with the greatest potential for growth. Jamaica's present viable mineral industry only dates back to 19S2 when Reynolds Jamaica Mines, Limited started the export of kiln dried metallurgical grade bauxite ore. This was followed shortly by the production and export of alumina by the then Alumina Jamaica Limited (now Alcan Jamaica, Limited), a subsidiary of the Aluminium Company of Canada. The commencement of this new and major industry followed a successful exploration and development programme which resulted largely from the keen perception and perseverance of two men. First, Mr. R.F. Innis observed that some of the cattle lands on the St. Ann plateau were potential sources of aluminium ore, and then Sir Alfred DaCosta persisted in attempts to interest aluminium companies in undertaking exploration work here. -

Rural Enterprise Development Initiative – Tourism Sector July 14, 2009

Jamaica Social Investment Fund Rural Enterprise Development Initiative – Tourism Sector July 14, 2009 Jamaica Social Investment Fund Rural Enterprise Development Initiative – Tourism Sector Rural Enterprise Development Initiative – Tourism Sector July 14, 2009 © PA Knowledge Limited 2009 PA Consulting Group 4601 N. Fairfax Drive Prepared by: Suite 600 Arlington, VA 22203 Tel: +1-571-227-9000 Fax: +1-571-227-9001 www.paconsulting.com Version: 1.0 Jamaica Social Investment Fund 7/14/09 FOREWORD This report is the compilation of deliverables under the Jamaica Social Investment Fund (JSIF) contract with PA Consulting Group (PA) to provide input in the design of the tourism sector elements of the Second National Community Development Project (NCDP2). Rural poverty is a major challenge for Jamaica, with the rural poverty rate twice the level of the urban areas. There is large potential for rural development, especially through closer linkages with the large and expanding tourism sector which offers numerous opportunities that are yet to be tapped. Improvements in productivity and competitiveness are key to realizing the potential synergies between tourism and small farmer agriculture. The objective of the proposed NCDP2 is to increase income and jobs in poor communities in targeted rural areas. Because of the focus on productive, income generating initiatives, the NCDP 2 project was named Rural Enterprise Development Initiative (REDI). The project l builds on the success of the community-based development approach utilized under NCDP1. The focus of income generation interventions will be supported by rural-based tourism development, agricultural technology improvements in small and medium farms, and the linkages between agriculture and tourism. -

Appendix, French Names, Supplement

685 APPENDIX Part 1. Speciesreported from the A.O.U. Check-list area with insufficient evidencefor placementon the main list. Specieson this list havebeen reported (published) as occurring in the geographicarea coveredby this Check-list.However, their occurrenceis considered hypotheticalfor one of more of the following reasons: 1. Physicalevidence for their presence(e.g., specimen,photograph, video-tape, audio- recording)is lacking,of disputedorigin, or unknown.See the Prefacefor furtherdiscussion. 2. The naturaloccurrence (unrestrained by humans)of the speciesis disputed. 3. An introducedpopulation has failed to becomeestablished. 4. Inclusionin previouseditions of the Check-listwas basedexclusively on recordsfrom Greenland, which is now outside the A.O.U. Check-list area. Phoebastria irrorata (Salvin). Waved Albatross. Diornedeairrorata Salvin, 1883, Proc. Zool. Soc. London, p. 430. (Callao Bay, Peru.) This speciesbreeds on Hood Island in the Galapagosand on Isla de la Plata off Ecuador, and rangesat seaalong the coastsof Ecuadorand Peru. A specimenwas takenjust outside the North American area at Octavia Rocks, Colombia, near the Panama-Colombiaboundary (8 March 1941, R. C. Murphy). There are sight reportsfrom Panama,west of Pitias Bay, Dari6n, 26 February1941 (Ridgely 1976), and southwestof the Pearl Islands,27 September 1964. Also known as GalapagosAlbatross. ThalassarchechrysosWma (Forster). Gray-headed Albatross. Diornedeachrysostorna J. R. Forster,1785, M6m. Math. Phys. Acad. Sci. Paris 10: 571, pl. 14. (voisinagedu cerclepolaire antarctique & dansl'Ocean Pacifique= Isla de los Estados[= StatenIsland], off Tierra del Fuego.) This speciesbreeds on islandsoff CapeHorn, in the SouthAtlantic, in the southernIndian Ocean,and off New Zealand.Reports from Oregon(mouth of the ColumbiaRiver), California (coastnear Golden Gate), and Panama(Bay of Chiriqu0 are unsatisfactory(see A.O.U. -

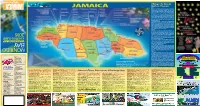

MONTEGO Identified

Things To Know Before You Go JAMAICA DO’S: At the airport: Use authorised pick up points for rented cars, taxis and buses. Use authorised transportation services and representatives. Transportation providers licensed by the Jamaica Tourist Board (JTB) bear a JTB sticker on the wind- screen. If you rent a car: Use car rental companies licensed by the Jamaica Tourist Board. Get directions before leaving the airport and rely on your map during your journey. Lock your car doors. Go to a service station or other well-lit public place if, while driving at night, you become lost or require as- sistance. Check your vehicle before heading out on the road each day. If problems develop, stop at the nearest service station and call to advise your car rental company. They will be happy to assist you. On the road: Remember to drive on the left. Observe posted speed limits and traffic signs. Use your seat belts. Always use your horn when approaching a blind corner on our nar- row and winding country roads. Try to travel with a group at night. While shopping: Carry your wallet discreetly. Use credit cards or traveller’s cheques for major purchases, if possible. In your hotel: Store valuables in a safety deposit box. Report suspicious-looking persons or activity to the front desk per- sonnel. Always lock your doors securely. DONT’S: At the airport: Do not Pack valuables (cash, jewellery, etc.) in 6 1 0 2 your luggage. Leave baggage unattended. If you rent a car: Do not Leave your engine running unattended. -

Distribution, Ecology, and Life History of the Pearly-Eyed Thrasher (Margarops Fuscatus)

Adaptations of An Avian Supertramp: Distribution, Ecology, and Life History of the Pearly-Eyed Thrasher (Margarops fuscatus) Chapter 6: Survival and Dispersal The pearly-eyed thrasher has a wide geographical distribution, obtains regional and local abundance, and undergoes morphological plasticity on islands, especially at different elevations. It readily adapts to diverse habitats in noncompetitive situations. Its status as an avian supertramp becomes even more evident when one considers its proficiency in dispersing to and colonizing small, often sparsely The pearly-eye is a inhabited islands and disturbed habitats. long-lived species, Although rare in nature, an additional attribute of a supertramp would be a even for a tropical protracted lifetime once colonists become established. The pearly-eye possesses passerine. such an attribute. It is a long-lived species, even for a tropical passerine. This chapter treats adult thrasher survival, longevity, short- and long-range natal dispersal of the young, including the intrinsic and extrinsic characteristics of natal dispersers, and a comparison of the field techniques used in monitoring the spatiotemporal aspects of dispersal, e.g., observations, biotelemetry, and banding. Rounding out the chapter are some of the inherent and ecological factors influencing immature thrashers’ survival and dispersal, e.g., preferred habitat, diet, season, ectoparasites, and the effects of two major hurricanes, which resulted in food shortages following both disturbances. Annual Survival Rates (Rain-Forest Population) In the early 1990s, the tenet that tropical birds survive much longer than their north temperate counterparts, many of which are migratory, came into question (Karr et al. 1990). Whether or not the dogma can survive, however, awaits further empirical evidence from additional studies. -

Distribution, Probable Evolution, and Fossil Record of West Indian Woodpeckers (Family Picidae)

DISTRIBUTION, PROBABLE EVOLUTION, AND FOSSIL RECORD OF WEST INDIAN WOODPECKERS (FAMILY PICIDAE) ALEXANDER CRUZ Department of Biology University of Colorado Boulder, Colorado 80302 R ESUMEN : La familia Picidae (carpinteros) esta representada en la fauna de las Antillas por dote especies vivientes y dos especies fosiles. Las primeras estan comprendidas en dos generos endemicos y seis generos de distribution mas amplia. Las segundas constan de un genero conocido y otro especimen de afinidad desconocida. Los carpinteros estan mejor representados en Cuba, donde hay cinco especies residentes en comparacion con las Antillas Menores, a excepcion de la Guadalupe, donde no hay especies residences. Durante la epoca glacial del Pleistocene el nivel del agua era inferior al actual y muchas zonas fueron expuestas. Durante esta epoca y posiblemente antes (Plioceno), la mayoria de la avifauna de las Antillas se derivo de las regiones continentals cercanas. Los carpinteros de las Antillas probablemente se originaron en tres diferentes regiones: Norte America, Centro America, y Sur America. HE family Picidae, whose fossil history Cayman, Gran Bahama, Abaco, and T dates back to the Lower Pliocene of Watling’s Island), Centurus radiolatus North America (Brodkorb, 1970) is re- (Jamaica), Centurus striatus (Hispaniola), presented in the West Indian faunal region Melanerpes portoricensis (Puerto Rico and (Fig. 1) by twelve living species, eleven Vieques), Melanerpes herminiero (Guada- resident and one migratory. These com- loupe), Colaptes auratus (Cuba and Grand prise two endemic genera (Nesoctites and Cayman), Colaptes (Nesoceleus) fernandi- Xiphiodiopicus) and six genera of a greater nae (Cuba), Xiphiodiopicus percussus (Cuba distribution (Colaptes, Melanerpes, Centu- and the Isle of Pines), Dendrocopos villosus rus, Sphyrapicus, Dendrocopos, and Cam- (New Providence, Andros, Grand Bahama pephilus). -

Appendix S1. List of the 719 Bird Species Distributed Within Neotropical Seasonally Dry Forests (NSDF) Considered in This Study

Appendix S1. List of the 719 bird species distributed within Neotropical seasonally dry forests (NSDF) considered in this study. Information about the number of occurrences records and bioclimatic variables set used for model, as well as the values of ROC- Partial test and IUCN category are provide directly for each species in the table. bio 01 bio 02 bio 03 bio 04 bio 05 bio 06 bio 07 bio 08 bio 09 bio 10 bio 11 bio 12 bio 13 bio 14 bio 15 bio 16 bio 17 bio 18 bio 19 Order Family Genera Species name English nameEnglish records (5km) IUCN IUCN category Associated NDF to ROC-Partial values Number Number of presence ACCIPITRIFORMES ACCIPITRIDAE Accipiter (Vieillot, 1816) Accipiter bicolor (Vieillot, 1807) Bicolored Hawk LC 1778 1.40 + 0.02 Accipiter chionogaster (Kaup, 1852) White-breasted Hawk NoData 11 p * Accipiter cooperii (Bonaparte, 1828) Cooper's Hawk LC x 192 1.39 ± 0.06 Accipiter gundlachi Lawrence, 1860 Gundlach's Hawk EN 138 1.14 ± 0.13 Accipiter striatus Vieillot, 1807 Sharp-shinned Hawk LC 1588 1.85 ± 0.05 Accipiter ventralis Sclater, PL, 1866 Plain-breasted Hawk LC 23 1.69 ± 0.00 Busarellus (Lesson, 1843) Busarellus nigricollis (Latham, 1790) Black-collared Hawk LC 1822 1.51 ± 0.03 Buteo (Lacepede, 1799) Buteo brachyurus Vieillot, 1816 Short-tailed Hawk LC 4546 1.48 ± 0.01 Buteo jamaicensis (Gmelin, JF, 1788) Red-tailed Hawk LC 551 1.36 ± 0.05 Buteo nitidus (Latham, 1790) Grey-lined Hawk LC 1516 1.42 ± 0.03 Buteogallus (Lesson, 1830) Buteogallus anthracinus (Deppe, 1830) Common Black Hawk LC x 3224 1.52 ± 0.02 Buteogallus gundlachii (Cabanis, 1855) Cuban Black Hawk NT x 185 1.28 ± 0.10 Buteogallus meridionalis (Latham, 1790) Savanna Hawk LC x 2900 1.45 ± 0.02 Buteogallus urubitinga (Gmelin, 1788) Great Black Hawk LC 2927 1.38 ± 0.02 Chondrohierax (Lesson, 1843) Chondrohierax uncinatus (Temminck, 1822) Hook-billed Kite LC 1746 1.46 ± 0.03 Circus (Lacépède, 1799) Circus buffoni (Gmelin, JF, 1788) Long-winged Harrier LC 1270 1.61 ± 0.03 Elanus (Savigny, 1809) Document downloaded from http://www.elsevier.es, day 29/09/2021. -

Guide Welcome Irie Isle

GUIDE WELCOME IRIE ISLE Seven Mile Beach Seven Mile Beach KNOWN FOR ITS STUNNING BEAUTY, Did you know? The traditional cooking technique FRIENDLY PEOPLE, LAND OF WOOD AND WATER known as jerk is said to have been invented by the island’s Maroons, VIBRANT CULTURE or runaway slaves. AND RICH HISTORY, Jamaica is a destination so dynamic and multifaceted you could visit hundreds of Negril, Frenchman’s Cove in Portland, Treasure Beach on the South Coast or the times and have a unique experience every single time. unique Dunn’s River Falls and Beach in Ocho Rios, there’s a beach for everyone. THERE’S NO BETTER Home of the legendary Bob Marley, arguably reggae’s most iconic and globally But if lounging on the sand all day is not your style, a visit to Jamaica may be recognised face, the island’s most popular musical export is an eclectic mix of just what the doctor ordered. With hundreds of fitness facilities and countless WORD TO DESCRIBE infectious beats and enchanting — and sometimes scathing — lyrics that can be running and exercise groups, the global thrust towards health and wellness has THE JAMAICAN heard throughout the island. The music is also celebrated through annual festivals spawned annual events such as the Reggae Marathon and the Kingston City such as Reggae Sumfest and Rebel Salute, where you could also indulge in Run. The get-fit movement has also influenced the creation of several health and EXPERIENCE Jamaica’s renowned culinary treats. wellness bars, as well as spa, fitness and yoga retreats at upscale resorts.