Žibuoklė Martinaitytė

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Veronika Vitaitė: Discoveries in Pianism

Veronika Vitaitė: Discoveries in Pianism Summary The book is devoted to the analysis of the performance skills, pedagog- ical and organisational activities of Veronika Vitaitė, a prominent cur- rent piano pedagogue, pianist, promoter of Lithuanian piano culture. Manifestations of the Professor’s personality in different fields of musi- cal activity, the universality of her works influenced the development of Lithuanian piano culture of the past decades: performance skills, a close relationship with Lithuanian composers encouraged the creation of piano duet, inspired the premiers of works of different genres; zeal- ous work, preparation of her students for international competitions yielded several generations of young pianists; intense organisational activities, long-time leadership of the Piano Department of the Lithua- nian Academy of Music and Theatre, constant supervision and care of training of young pianists of the Republic laid strong foundations for a further development of piano excellence. Thus far Veronika Vitaitė’s intense and multi-faceted activities have not been thoroughly discussed and properly assessed. Whereby the present monograph it is sought to fill the existing gap. In preparing the book, the following works by Lithuanian researchers were used: col- lections of articles compiled by Kęstutis Grybauskas (1984), Veronika Vitaitė (1993), studies of the development of the art of piano by Mariam Azizbekova (1991, 1998, 1999), Liucija Drąsutienė (1996, 2004, 2015), Eugenijus Ignatonis (1997, 2003, 2010), Rita Aleknaitė-Bieliauskienė (2003, 2014, 2017), Ramunė Kryžauskienė (2004, 2007), scientific in- sights of Leonidas Melnikas (2006, 2007), Lina Navickaitė-Martinelli (2013). To discuss Veronika Vitaitė’s artistic activities, we drew on the reviews of her concerts, and to analyse general principles of her teach- ing methods, reminiscences of her former students and a questionnaire survey were used, lessons of the experienced pedagogue, as well as workshops and master classes that she conducted were attended. -

19 September 2020

19 September 2020 12:01 AM Johann Strauss II (1825-1899) Spanischer Marsch Op 433 ORF Radio Symphony Orchestra, Peter Guth (conductor) ATORF 12:06 AM Jose Marin (c.1618-1699) No piense Menguilla ya Montserrat Figueras (soprano), Rolf Lislevand (baroque guitar), Pedro Estevan (percussion), Arianna Savall (harp) ATORF 12:12 AM Arcangelo Corelli (1653-1713) Sonata da Chiesa in B flat major, Op 1 no 5 London Baroque DEWDR 12:19 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) Symphony no 4 in D major, K.19 BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, Osmo Vanska (conductor) GBBBC 12:32 AM Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849) From 24 Preludes for piano, Op 28: Nos. 4-11, 19 and 17 Sviatoslav Richter (piano) PLPR 12:48 AM Henryk Wieniawski (1835-1880) Violin Concerto no 2 in D minor, Op 22 Mariusz Patyra (violin), Polish Radio Orchestra, Wojciech Rajski (conductor) PLPR 01:12 AM Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) 4 Songs for women's voices, 2 horns and harp, Op 17 Danish National Radio Choir, Leif Lind (horn), Per McClelland Jacobsen (horn), Catriona Yeats (harp), Stefan Parkman (conductor) DKDR 01:27 AM Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) Suite in E major BWV.1006a Konrad Junghanel (lute) DEWDR 01:48 AM Franz Schubert (1797-1828), Friedrich Schiller (author) Sehnsucht ('Longing') (D.636) - 2nd setting Christoph Pregardien (tenor), Andreas Staier (pianoforte) DEWDR 01:52 AM Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) Concerto for 2 trumpets and orchestra in C major, RV.537 Anton Grcar (trumpet), Stanko Arnold (trumpet), RTV Slovenia Symphony Orchestra, Marko Munih (conductor) SIRTVS 02:01 AM Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Piano Concerto no 1 in C major, Op 15 Martin Stadtfeld (piano), NDR Radio Philharmonic Orchestra, Andrew Manze (conductor) DENDR 02:35 AM George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) Will the sun forget to streak, from 'Solomon, HWV.67', arr. -

Beata Adamczyk Cultural Cooperation Between Nations As an Important

Beata Adamczyk Cultural cooperation between nations as an important factor of sustainable social development of the region of Central and Eastern Europe in the European Union : (for instance Poland and Lithuania) Studia Ecologiae et Bioethicae 5, 225-267 2007 Beata ADAMCZYK UW Warszawa Cultural cooperation between nations as an important factor of sustainable social development of the region of Central and Eastern Europe in the European Union (for instance Poland and Lithuania) Motto: So that the spirits of the dead leave us in peace... (Aby duchy umarłych zostawiły nas w spokoju...) CZESŁAW MIŁOSZA Cultural cooperation between nations is mainly based on pacts entered by the government of the Republic of Poland and the government of the Republic of Lithuania, on cooperation between academies and cultural facilities, and on collaboration of all nations living in the given area with respect to issues important to local communities, ^ e message of cultural cooperation is social and cultural integration. Cultural and social co-operation among nations lived in East and Central Europe has been sprung up over many centuries. In the 20th century, the nations of the part of Europe were subjected to an attempt to standardise their national cultures by means of introducing the socialist realist culture. According to purposes of contemporary authorities culture was created only officially. In language of the contemporary system, social issues were taken into account mainly in the mass aspect. ^ e author of article is a graduate of the Institute of Librarianship and Information Science at Warsaw University and because of it in the article mainly she treats of bookseller’s and publishing connected with Vilnius. -

Balys DVARIONAS (1904-1972) Complete Works for Violin and Piano Sonata-Ballade • Pezzo Elegiaco • Three Pieces

Balys DVARIONAS (1904-1972) Complete Works for Violin and Piano Sonata-Ballade • Pezzo elegiaco • Three Pieces Justina Auškelytė, Violin • Cesare Pezzi, Piano Balys Dvarionas (1904-1972) Complete Works for Violin and Piano Balys Dvarionas was one of the most prominent figures in Igor Stravinsky and Sergey Prokofiev, among others. The pianist, and his son, the violinist. There can be little doubt Sonata was meant to be a one-movement composition the field of Lithuanian (and indeed Baltic) musical culture. last time Dvarionas appeared on stage was on May 12, as to why Dvarionas’ instrumental chamber works are with the main theme reprised in the recapitulation. During A polymath, he excelled as a pianist, conductor, 1972 at the Lithuanian National Philharmonic in Vilnius, said to possess an especially personal quality. In the creative process each musical idea inspired the next, composer and pedagogue. Dvarionas was born in the where together with the Lithuanian Chamber Orchestra composing music for his children, the composer and so the work can be viewed as one constantly evolving Latvian harbour city of Liepaja. His father was a Roman he played Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 1 in D major, inadvertently developed a particularly original chamber beautiful episodic sequence. A colleague of the composer Catholic church organist, and as a result the young K.107 and conducted Schubert’s Mass No. 2 in G major music idiom, where the interplay between parts relies on once described the work in the following terms: “…when Dvarionas received his first music lessons at home. He D.167. an uninhibited bond between performers. -

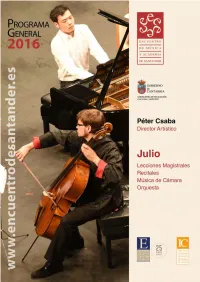

Programa2016.Pdf

l Encuentro de Música y Academia cumple un año más el reto de superarse a sí mismo. La programación de 2016 combina a la perfección la academia, la experiencia y el virtuosismo de los más grandes, como el maestro Krzysztof Penderecki, con la frescura, las ganas y el entusiasmo de los jóvenes músicos Eparticipantes en esta cita ineludible cada verano en Cantabria. Más de 50 conciertos en los escenarios del Palacio de Festivales de Cantabria, en el Palacio de La Magdalena y en otras 22 localidades acercarán la Música con mayúsculas a todos los rincones de la Comunidad Autónoma para satisfacer a un público exigente y siempre ávido de manifestaciones culturales. Para esta tierra, es un privilegio la oportunidad de engrandecer su calendario cultural con un evento de tanta relevancia nacional e internacional. Así pues, animo a todos los cántabros y a quienes nos visitan en estas fechas estivales a disfrutar al máximo de los grandes de la música y a aportar con su presencia la excelente programación que, un verano más, nos ofrece el Encuentro de Música y Academia. Miguel Ángel Revilla Presidente del Gobierno de Cantabria esde hace ya 16 años, el Encuentro de Música y Academia de Santander sigue fielmente las líneas maestras que lo han convertido en un elemento muy prestigioso del verano musical europeo. En Santander —que es una delicia en el mes de julio— se reúnen jóvenes músicos seleccionados uno a uno mediante audición en las escuelas de mayor prestigio Dde Europa, incluida, naturalmente, la Reina Sofía de Madrid. Comparten clases magistrales, ensayos y conciertos con una serie igualmente extraordinaria de profesores, los más destacados de cada instrumento en el panorama internacional. -

Dvarionas Vadim Gluzman Residentie Orkest Den Haag Neeme Järvi

Erich Wolfgang Korngold © Korngold Family Estate KORNGOLD · DVARIONAS VADIM GLUZMAN RESIDENTIE ORKEST DEN HAAG NEEME JÄRVI Balys Dvarionas Photo kindly provided by the Lithuanian Music Information and Publishing Centre BIS-CD-1822 BIS-CD-1822_f-b.indd 1 10-05-17 10.55.23 KORNGOLD, Erich Wolfgang (1897–1957) Concerto in D major for Violin and Orchestra 24'59 Op. 35 (1945) (Schott) 1 I. Moderato nobile 9'08 2 II. Romance. Andante 8'39 3 III. Finale. Allegro assai vivace 6'59 DVARIONAS, Balys (1904–72) · 4 Pezzo elegiaco ‘Prie ežerelio’ (‘By the lake’) 5'18 (1946–47) for violin and orchestra (Karthause-Schmülling) Concerto in B minor for Violin and Orchestra 29'44 (1948) (Karthause-Schmülling) 5 I. Andante semplice – Allegro strepitoso 15'31 6 II. Andante molto sostenuto 8'36 7 III. Vivo 5'23 TT: 60'55 Vadim Gluzman violin Residentie Orkest Den Haag Neeme Järvi conductor 2 his programme features three works for violin and orchestra composed in the three years following the end of World War II, by two composers whose Tfates were very different. One is world-famous, at least for his film music – the other known, outside his native land, only to a few cognoscen ti; one was an exile from his homeland – the other an ‘internal exile’ within his homeland, his music celebrating his people’s national aspirations under a suc ces sion of over bear - ing foreign powers. But the two are united in their music’s heartfelt and unabashed romanticism. Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s early career resembles that of Mozart, with whom he shared one of his forenames. -

Landsbergis, Vytautas

LIETUVOS NACIONALINĖ MARTYNO MAŽVYDO BIBLIOTEKA VADOVYBĖS INFORMACIJOS SKYRIUS Tel. 239 8558 0BVYTAUTO LANDSBERGIO KNYGŲ BIBLIOGRAFIJA 1963 – 2012 m. Landsbergis, Vytautas. Kaip muzika atspindi gamtą / Vytautas Landsbergis. - Vilnius : [s.n.], 1963. - 24 p. - Antr. p. viršuje: Lietuvos TSR polit. ir moksl. žinių skleidimo draugija ir Lietuvos TSR kompozitorių s-ga. - Rankraščio teisėmis. Landsbergis, Vytautas. Muzika ir literatūra : (medžiaga lektoriui) / Vytautas Landsbergis. - Vilnius : [s.n.], 1964. - 2 t. - Antr. p. viršuje: Lietuvos TSR "Žinijos draugija. Lietuvos TSR Kompozitorių sąjunga. Meno mokslo-metodinė taryba. Landsbergis, Vytautas. M.K. Čiurlionis ir jo muzikos kūriniai = М.К. Чюрленис и его музыкальные произведения = M.K. Čiurlionis and his musical work : [M.K. Čiurlionio 90-jų gimimo metinėms skirtas leidinys] / [V. Landsbergis ; apipavidalino dail. Arūnas Tarabilda]. - Vilnius : [s.n.], 1965. - 23, [1] p., įsk. virš. : iliustr., nat. - Aut. nurodytas str. gale. - Virš. antr.: M.K. Čiurlionis. Landsbergis, Vytautas. Pavasario sonata / Vytautas Landsbergis. - Vilnius : Vaga, 1965 (Kaunas : Valst. K. Poželos sp.). - 351, [1] p., [10] iliustr. lap. : nat., iliustr. - Vertimai: Соната весны. Ленинград : Музыка, 1971. Čiurlionis, Mikalojus Konstantinas. Zodiako ženklai : [reprodukcijos] / M.K. Čiurlionis. - Vilnius : Vaga, 1967. - 1 apl. (19 p., 12 iliustr. lap.). - Santr. rus., angl., pranc., vok. Kn. taip pat: Įž. str. / V. Landsbergis. Landsbergis, Vytautas. Соната весны : творчество М.К. Чюрлeниса / В. Ландсбергис. - Ленинград : Музыка, 1971 (Вильнюс : Вайздас). - 327 p., [19] iliustr., portr., nat. lap. : faks., iliustr., nat. - Versta iš: Pavasario sonata. Vilnius : Vaga, 1965. Čiurlionis, Mikalojus Konstantinas. Pasaulio sutvėrimas [Grafika] : [reprodukcijos] / M.K. Čiurlionis. - Vilnius : Vaga, 1972 (Kaunas : K. Poželos sp.). - 1 apl. (13 atvirukų) : spalv. - Gretut. tekstas liet., angl., rus. Leid. taip pat: Pasaulio sutvėrimas / V. -

Regimantas Gudelis DAINŲ ŠVENTĖS IR JUNGTINIO

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Klaipeda University Open Journal Systems 160 RES HUMANITARIAE XIII ISSN 1822-7708 Regimantas Gudelis – Klaipėdos universiteto Chorvedy- bos ir pedagogikos katedros profesorius, socialinių mokslų daktaras, Muzikologijos instituto vyriausiasis mokslinis bendradarbis. Moksliniai interesai: chorinis menas, chorinio meno istorija, dainų šventės. Adresas: Kristijono Donelaičio g. 4, LT-92144 Klaipėda. Tel. (+370 ~ 46) 252 836. El. paštas: [email protected]. Regimantas Gudelis – Ph. D. in Social Sciences, Research Fellow at the Institute of Musicology, Prof. at the De- partment of Conducting and Pedagogics, Faculty of Arts, Klaipėda University (Lithuania). Research interests: choral music, history of choral music, song festival. Address: Kristijono Donelaičio str. 4, LT-92144 Klaipėda. Telephone: (+370 ~ 46) 252 836. E-mail: [email protected]. Regimantas Gudelis Klaipėdos universitetas DAINŲ ŠVENTĖS IR JUNGTINIO CHORO MENINĖS-DVASINĖS ENERGIJOS KLAUSIMU Anotacija Straipsnyje nagrinėjama Lietuvos dainų šventėse pasirodantis jungtinis choras – jo žanrinė specifika bei meninė-dvasinė energija. Pagrindinė tiriamoji medžiaga – tokio choro diri- gentų nuomonės, surinktos interviu metodu. Dainų šventes ir jungtinį chorą dirigentai laiko daugiareikšmiu socialiniu-meniniu fenomenu, vertingu tiek tautos chorinės kultūros, tiek ir tautiškumo aspektais. Choro meninė-dvasinė energija ir jos proveržio intensyvumas priklauso nuo jo meninio atlikimo techninės kokybės, meninės interpretacijos ir atlikėjų sutelktumo. Dirigentas – šių procesų įkvėpėjas ir koordinatorius. PAGRINDINIAI ŽODŽIAI: dainų šventė, jungtinis choras, dirigentas, muzikos interpre- tacija, meninė-dvasinė energija. Abstract The article analysis the joint choir performing in the Song Festival – its genre peculiarity and artistic-spiritual energy. The main research material consists of the interviews with the conductors of such choirs. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE UPDATED January 17, 2017 November 1, 2016 ARTIST and PROGRAM CHANGE Contact: Katherine E. Johnson (212) 875-5718; [email protected]

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE UPDATED January 17, 2017 November 1, 2016 ARTIST AND PROGRAM CHANGE Contact: Katherine E. Johnson (212) 875-5718; [email protected] LONG YU TO CONDUCT CHINA PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA, PRESENTED BY THE NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC PROKOFIEV’s Violin Concerto No. 2 with JULIAN RACHLIN SHOSTAKOVICH’s Symphony No. 5 December 11, 2016 NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC IN SIXTH ANNUAL CHINESE NEW YEAR CONCERT and GALA U.S. PREMIERE of CHEN Qigang’s Joie Éternelle with Trumpet Player ALISON BALSOM PUCCINI’s Selection from Turandot and Traditional Chinese Folk Songs with Soprano SUMI JO SAINT-SAËNS’s Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso with Concertmaster FRANK HUANG January 31, 2017 The New York Philharmonic will present two programs honoring its strong ties to China, both led by Long Yu: the China Philharmonic Orchestra will perform at David Geffen Hall on December 11, 2016, and the New York Philharmonic will perform its sixth annual Chinese New Year Concert and Gala, January 31, 2017. Both programs celebrate the cultural exchange between China and the U.S., particularly the Philharmonic’s connections to China. China Philharmonic Orchestra The New York Philharmonic will present the China Philharmonic Orchestra, led by Long Yu, its Music Director, at David Geffen Hall on December 11, 2016, at 3:00 p.m. The program will feature Prokofiev’s Violin Concerto No. 2, with Julian Rachlin as soloist, and Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 5. Long Yu co-founded the China Philharmonic Orchestra in 2000, and has since served as its artistic director and chief conductor. The orchestra’s appearance at David Geffen Hall, presented by the New York Philharmonic, is part of its 2016 Tour of the Americas. -

Vilde Frang, Violin

VILDE FRANG, VIOLIN Vilde is the recipient of the 2012 Credit Suisse Young Artists Award and will perform with the Vienna Philharmonic and Bernard Haitink at the Lucerne Summer Music Festival in September 2012. Noted particularly for her superb musical expression, as well as her well- developed virtuosity and musicality, Vilde Frang has established herself as one of the leading young violinists of her generation since she was engaged by Mariss Jansons at the age of twelve to debut with Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra. Highlights among her recent and forthcoming engagements include performances with Mahler Chamber Orchestra, Kremerata Baltica, Academy of St. Martin in the Fields, BBC Symphony, Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks, Konzerthausorchester Berlin, HR- Sinfonieorchester Frankfurt, Tonhalle-Orchester Zurich, Russian National Orchestra, Rotterdam Philharmonic, the NHK Symphony in Tokyo and Orchestre Philharmonique de Monte-Carlo, with conductors including Ivan Fischer, Paavo Järvi, Vladimir Ashkenazy, Mariss Jansons, David Zinman, Vassily Sinaisky, Esa-Pekka Salonen and Gianandrea Noseda. She appears as a recitalist and chamber musician at festivals in Schleswig- Holstein, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Rheingau, Lockenhaus, Gstaad, Verbier and Lucerne. Amongst her collaborators were Gidon Kremer, Yuri Bashmet, Martha Argerich, Julian Rachlin, Leif Ove Andsnes and Maxim Vengerov, and together with Anne-Sophie Mutter she has toured in Europe and the US, playing Bach's Double Concerto with Camerata Salzburg. After her 2007 debut with London Philharmonic Orchestra, Vilde was immediately re-engaged for a concert with the orchestra and Vladimir Nordic Artists Management / Denmark VAT number: DK29514143 http://nordicartistsmanagement.com Jurowski at the Royal Festival Hall in the 2009 season, followed by a recital at Wigmore Hall. -

Jansen/Maisky/ Argerich Trio Tuesday 6 February 2018 7.30Pm, Hall

Jansen/Maisky/ Argerich Trio Tuesday 6 February 2018 7.30pm, Hall Beethoven Cello Sonata in G minor, Op 5 No 2 Shostakovich Piano Trio No 2 in E minor, Op 67 interval 20 minutes Schumann Violin Sonata No 1 in A minor, Op 105 Mendelssohn Piano Trio No 1 in D minor, Op 49 Janine Jansen violin Mischa Maisky cello Martha Argerich piano Adriano Heitman Adriano Part of Barbican Presents 2017–18 Programme produced by Harriet Smith; printed by Trade Winds Colour Printers Ltd; advertising by Cabbell (tel. 020 3603 7930) Confectionery and merchandise including organic ice cream, quality chocolate, nuts and nibbles are available from the sales points in our foyers. Please turn off watch alarms, phones, pagers etc during the performance. Taking photographs, capturing images or using recording devices during a performance is strictly prohibited. If anything limits your enjoyment please let us know The City of London during your visit. Additional feedback can be given Corporation is the founder and online, as well as via feedback forms or the pods principal funder of located around the foyers. the Barbican Centre Welcome Tonight we are delighted to welcome three friend Ivan Sollertinsky, an extraordinarily musicians so celebrated that they need no gifted man in many different fields. introduction. Martha Argerich and Mischa Maisky have been performing together We begin with Beethoven, and his Second for more than four decades, while Janine Cello Sonata, a work that is groundbreaking Jansen is a star of the younger generation. for treating string instrument and piano equally and which ranges from sheer Together they present two vastly different wit to high drama. -

Strategy Academy 2020–2030

STRATEGY 2020–2030 OF THE LITHUANIAN ACADEMY OF MUSIC AND THEATRE Approved by Resolution No 6-TS of the LAMT Council of 19 December 2019 Table of contents 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 3 2. LAMT TODAY ................................................................................................................................ 4 2.1. STUDIES ................................................................................................................................................ 4 2.2. ART ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 2.3. RESEARCH ............................................................................................................................................. 7 2.4. OTHER ACTIVITIES ................................................................................................................................ 8 2.5. INFRASTRUCTURE ................................................................................................................................. 8 2.6. FINANce ................................................................................................................................................ 9 2.7. PARTNESHIPS AND COOPERATION ...................................................................................................... 9 3. COMPETITIVE ENVIRONMENT IN