Jansen/Maisky/ Argerich Trio Tuesday 6 February 2018 7.30Pm, Hall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Voice Types in Opera

Voice Types in Opera In many of Central City Opera’s educational programs, we spend some time explaining the different voice types – and therefore character types – in opera. Usually in opera, a voice type (soprano, mezzo soprano, tenor, baritone, or bass) has as much to do with the SOUND as with the CHARACTER that the singer portrays. Composers will assign different voice types to characters so that there is a wide variety of vocal colors onstage to give the audience more information about the characters in the story. SOPRANO: “Sopranos get to be the heroine or the princess or the opera star.” – Eureka Street* “Sopranos always get to play the smart, sophisticated, sweet and supreme characters!” – The Great Opera Mix-up* A soprano is a woman’s voice type. There are many different kinds of sopranos within the general category: coloratura, lyric, and spinto are a few. Coloratura soprano: Diana Damrau as The Queen of the Night in The Magic Flute (Mozart): https://youtu.be/dpVV9jShEzU Lyric soprano: Mirella Freni as Mimi in La bohème (Puccini): https://youtu.be/yTagFD_pkNo Spinto soprano: Leontyne Price as Aida in Aida (Verdi): https://youtu.be/IaV6sqFUTQ4?t=1m10s MEZZO SOPRANO: “There are also mezzos with a lower, more exciting woman’s voice…We get to be magical or mythical characters and sometimes… we get to be boys.” – Eureka Street “Mezzos play magnificent, magical, mysterious, and miffed characters.” – The Great Opera Mix-up A mezzo soprano is a woman’s voice type. Just like with sopranos, there are different kinds of mezzo sopranos: coloratura, lyric, and dramatic. -

Roman Simovic Violin

Roman Simovic violin Roman Simovic's brilliant virtuosity and seemingly-inborn musicality, fueled by a limitless imagination, has taken him throughout all continents performing on many of world's leading stages including the Carnegie Hall, Bolshoi Hall of the Tchaikovsky Conservatory, Mariinsky Hall in St. Petersburg, Grand Opera House in Tel-Aviv, Victoria Hall in Geneva, Rudolfinum Hall in Prague, Barbican Hall in London, Art Centre in Seoul, Grieg Hall in Bergen, Rachmaninov Hall in Moscow, to name a few. Roman Simovic has been awarded prizes at numerous international competitions among which are: "Premio Rodolfo Lipizer" (Italy, first prize winner and winner of 12 Audience prizes), Sion-Valais (Switzerland), Yampolsky Violin Competition (Russia) and the Henryk Wieniawski Violin Competition (Poland), placing him among the foremost violinists of his generation. As soloist, Roman has appeared with the world leading orchestras: London Symphony Orchestra, Mariinsky Theatre Symphony Orchestra, Teatro Regio Torino, Symphony Nova Scotia (Canada), Franz Liszt Chamber Orchestra (Hungary), Camerata Bern (Switzerland), Camerata Salzburg (Austria), CRR Chamber Orchestra (Turkey), Poznan Philharmonia, Prague Philharmonia, North Brabant (Holland)...with conductors like: Valery Gergiev, Antonio Pappano, Daniel Harding, Gianandrea Noseda, Kristian Jarvi, Jiri Belohlavek, Pablo Heras Casado, Nikolai Znaider. In 2021 Roman will appear as a soloist with the Quebec Symphony Orchestra (Canada) and the conductor Fabien Gabel, RTVE Symphony Orchestra (Spain) where Roman will be playing and directing Prokofiev Violin Concerto No.2, I Pomeriggi Musicali (Italy) and conductor Alessandro Cadario, Braunschweig Staatsorchester and conductor Srba Dinić (Germany), Ulster Orchestra and conductor Daniele Rustioni (Northern Ireland), Malta Philarmonic Orchestra and conductor Sergey Smbatyan (Malta), Kristiansand Chamber Orchestra playing and directing (Norway), London Symphony Orchestra and conductor Sir Simon Rattle playing Miklos Rosza Violin Concerto, among others. -

Emphasis on Female Conductors and Composers the Royal Concertgebouw Presents Its Programme for the 2018-2019 Season

Press release Emphasis on female conductors and composers The Royal Concertgebouw presents its programme for the 2018-2019 season Amsterdam, 26th February 2018 – For its programme for the 2018-2019 season, The Royal Concertgebouw has decided to put an emphasis on female conductors and composers. Together with the LUDWIG music collective, Barbara Hannigan is set to return to conduct her first opera, The Rake’s Progress by Stravinsky. For her Royal Concertgebouw debut, Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla will be bringing with her the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, of which she is chief conductor. Susanna Mälkki will also be heading her ‘very own’ Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra. It will also be the first time that The Royal Concertgebouw welcomes a female composer in residence, Tansy Davies, from Great Britain. She will reside in Amsterdam for a few months to, among other things, compose new works for Asko|Schönberg. In the Rising Stars series, the audience will hear commissioned works by Roxanna Panufnik and Camille Pépin, with attention also being paid to female composers such as Alma Mahler, Clara Schumann and Fanny Mendelssohn. The Italian composer and violinist Alba Rosa Viëtor will take centre stage during the one-day festival Alba Rosa Viva!. Her works will be supported by the works of Henriëtte Bosmans, Cécile Chaminade and Rosy Wertheim. Three female ‘Sharp thinkers’ are also set to make an appearance: Petra Stienen, Griet Op de Beeck and Aaltje van Zweden. Violinist Janine Jansen will display her versatility with three concerts in the Main Hall: in a recital together with pianist Alexander Gavrylyuk, and as a soloist with the Swedish Radio Orchestra and the Chamber Orchestra of Europe. -

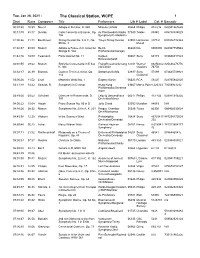

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Tue, Jan 26, 2021 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 10:39 Mozart Adagio in B minor, K. 540 Mitsuko Uchida 00264 Philips 412 616 028941261625 00:13:3945:17 Dvorak Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. du Pre/Swedish Radio 07040 Teldec 85340 685738534029 104 Symphony/Celibidache 01:00:2631:11 Beethoven String Quartet No. 9 in C, Op. Tokyo String Quartet 04508 Harmonia 807424 093046742362 59 No. 3 Mundi 01:32:3708:09 Mozart Adagio & Fugue in C minor for Berlin 06660 DG 0005830 028947759546 Strings K. 546 Philharmonic/Karajan 01:42:1618:09 Telemann Paris Quartet No. 11 Kuijken 04867 Sony 63115 074646311523 Bros/Leonhardt 02:01:5529:22 Mozart Sinfonia Concertante in E flat, Frang/Rysanov/Arcang 12341 Warner 08256462 825646276776 K. 364 elo/Cohen Classics 76776 02:32:1726:39 Brahms Clarinet Trio in A minor, Op. Stoltzman/Ax/Ma 02937 Sony 57499 074645749921 114 Classical 03:00:2611:52 Liszt Mephisto Waltz No. 1 Evgeny Kissin 06623 RCA 58420 828765842020 03:13:1834:42 Strauss, R. Symphony in D minor Hong Kong 03667 Marco Polo 8.220323 73009923232 Philharmonic/Scherme rhorn 03:49:0009:52 Schubert Overture to Rosamunde, D. Leipzig Gewandhaus 00217 Philips 412 432 028941243225 797 Orchestra/Masur 04:00:2215:04 Haydn Piano Sonata No. 50 in D Julia Cload 02053 Meridian 84083 N/A 04:16:2628:32 Mozart Symphony No. 29 in A, K. 201 Prague Chamber 05596 Telarc 80300 089408030024 Orch/Mackerras 04:45:58 12:20 Webern In the Summer Wind Philadelphia 10424 Sony 88725417 887254172024 Orchestra/Ormandy 202 04:59:4806:23 Lehar Merry Widow Waltz Richard Hayman 08261 Naxos 8.578041- 747313804177 Symphony 42 05:07:11 21:52 Rachmaninoff Rhapsody on a Theme of Entremont/Philadelphia 04207 Sony 46541 07464465412 Paganini, Op. -

Download Booklet

559199 bk Helps US 12/01/2004 11:54 am Page 8 Robert HELPS AMERICAN CLASSICS (1928-2001) ROBERT HELPS Shall We Dance Piano Quartet • Postlude • Nocturne Spectrum Concerts Berlin 8.559199 8 559199 bk Helps US 12/01/2004 11:54 am Page 2 Robert Helps (1928-2001) ROBERT HELPS (1928-2001) Shall We Dance • Piano Quartet • Postlude • Nocturne • The Darkened Valley (John Ireland) 1 Shall We Dance for Piano (1994) 11:09 Robert Helps was Professor of Music at the University of Minneapolis, and elsewhere. His later concerts included Piano Quartet for Piano, Violin, Viola and Cello (1997) 25:55 South Florida, Tampa, and the San Francisco memorial solo recitals of the music of renowned Conservatory of Music. He was a recipient of awards in American composer Roger Sessions at both Harvard and 2 I. Prelude 10:24 composition from the National Endowment for the Arts, Princeton Universities, an all-Ravel recital at Harvard, 3 II. Intermezzo 2:24 the Guggenheim, Ford, and many other foundations, and and a solo recital in Town Hall, NY. His final of a 1976 Academy Award from the Academy of Arts compositions include Eventually the Carousel Begins, for 4 III. Scherzo 3:02 and Letters. His orchestral piece Adagio for Orchestra, two pianos, A Mixture of Time for guitar and piano, which 5 IV. Postlude 8:12 which later became the middle movement of his had its première in San Francisco in June 1990 by Adam 6 V. Coda – The Players Gossip 1:53 Symphony No. 1, won a Fromm Foundation award and Holzman and the composer, The Altered Landscape was premièred by Leopold Stokowski and the Symphony (1992) for organ solo and Shall We Dance (1994) for 7 Postlude for Horn, Violin and Piano (1964) 9:11 of the Air (formerly the NBC Symphony) at the piano solo, Piano Trio No. -

19 September 2020

19 September 2020 12:01 AM Johann Strauss II (1825-1899) Spanischer Marsch Op 433 ORF Radio Symphony Orchestra, Peter Guth (conductor) ATORF 12:06 AM Jose Marin (c.1618-1699) No piense Menguilla ya Montserrat Figueras (soprano), Rolf Lislevand (baroque guitar), Pedro Estevan (percussion), Arianna Savall (harp) ATORF 12:12 AM Arcangelo Corelli (1653-1713) Sonata da Chiesa in B flat major, Op 1 no 5 London Baroque DEWDR 12:19 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) Symphony no 4 in D major, K.19 BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, Osmo Vanska (conductor) GBBBC 12:32 AM Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849) From 24 Preludes for piano, Op 28: Nos. 4-11, 19 and 17 Sviatoslav Richter (piano) PLPR 12:48 AM Henryk Wieniawski (1835-1880) Violin Concerto no 2 in D minor, Op 22 Mariusz Patyra (violin), Polish Radio Orchestra, Wojciech Rajski (conductor) PLPR 01:12 AM Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) 4 Songs for women's voices, 2 horns and harp, Op 17 Danish National Radio Choir, Leif Lind (horn), Per McClelland Jacobsen (horn), Catriona Yeats (harp), Stefan Parkman (conductor) DKDR 01:27 AM Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) Suite in E major BWV.1006a Konrad Junghanel (lute) DEWDR 01:48 AM Franz Schubert (1797-1828), Friedrich Schiller (author) Sehnsucht ('Longing') (D.636) - 2nd setting Christoph Pregardien (tenor), Andreas Staier (pianoforte) DEWDR 01:52 AM Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) Concerto for 2 trumpets and orchestra in C major, RV.537 Anton Grcar (trumpet), Stanko Arnold (trumpet), RTV Slovenia Symphony Orchestra, Marko Munih (conductor) SIRTVS 02:01 AM Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Piano Concerto no 1 in C major, Op 15 Martin Stadtfeld (piano), NDR Radio Philharmonic Orchestra, Andrew Manze (conductor) DENDR 02:35 AM George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) Will the sun forget to streak, from 'Solomon, HWV.67', arr. -

Download the Concert Programme (PDF)

London Symphony Orchestra Living Music Sunday 5 February 2017 7pm Barbican Hall LSO ARTIST PORTRAIT: JANINE JANSEN Sibelius The Oceanides Bernstein Serenade INTERVAL Nielsen Symphony No 4 London’s Symphony Orchestra (‘The Inextinguishable’) Sir Antonio Pappano conductor Janine Jansen violin Concert finishes approx 8.55pm Filmed and broadcast live by Mezzo 2 Welcome 5 February 2017 Welcome Living Music Kathryn McDowell In Brief Welcome to tonight’s LSO concert at the Barbican, LSO 2017/18 SEASON NOW ON SALE which marks the start of this season’s Artist Portrait series, focusing on violin soloist Janine Jansen. The LSO’s inaugural season with Sir Simon Rattle as Music Director is now on sale. Beginning with a ten- The LSO has performed with Janine Jansen regularly day celebration to welcome him in September, the for many years all over the world, and she is a season features concerts to mark 100 years since favourite with our audiences and with the musicians the birth of Bernstein and 100 years since the death of the Orchestra. Across three concerts we will of Debussy, world premieres from British composers, hear her perform a wide range of repertoire, from the beginning of a Shostakovich symphonies cycle, Bernstein’s Serenade tonight to Brahms’ Violin and a performance of Stockhausen’s Gruppen in the Concerto in March, and finally the Berg Violin Concerto Turbine Hall at Tate Modern. in April, showing the many different sides of her celebrated artistry. alwaysmoving.lso.co.uk This evening’s programme is conducted by another good friend of the LSO, Sir Antonio Pappano. -

Rezension Für: Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin

Rezension für: Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin Edition Friedrich Gulda – The early RIAS recordings Ludwig van Beethoven | Claude Debussy | Maurice Ravel | Frédéric Chopin | Sergei Prokofiev | Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart 4CD aud 21.404 Radio Stephansdom CD des Tages, 04.09.2009 ( - 2009.09.04) Aufnahmen, die zwischen 1950 und 1959 entstanden. Glasklar, "gespitzter Ton" und... Full review text restrained for copyright reasons. Neue Musikzeitung 9/2009 (Andreas Kolb - 2009.09.01) Konzertprogramm im Wandel Konzertprogramm im Wandel Full review text restrained for copyright reasons. Piano News September/Oktober 2009, 5/2009 (Carsten Dürer - 2009.09.01) Friedrich Guldas frühe RIAS-Aufnahmen Friedrich Guldas frühe RIAS-Aufnahmen Full review text restrained for copyright reasons. page 1 / 388 »audite« Ludger Böckenhoff • Tel.: +49 (0)5231-870320 • Fax: +49 (0)5231-870321 • [email protected] • www.audite.de DeutschlandRadio Kultur - Radiofeuilleton CD der Woche, 14.09.2009 (Wilfried Bestehorn, Oliver Schwesig - 2009.09.14) In einem Gemeinschaftsprojekt zwischen dem Label "audite" und Deutschlandradio Kultur werden seit Jahren einmalige Aufnahmen aus den RIAS-Archiven auf CD herausgebracht. Inzwischen sind bereits 40 CD's erschienen mit Aufnahmen von Furtwängler und Fricsay, von Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau u. v. a. Die jüngste Produktion dieser Reihe "The Early RIAS-Recordings" enthält bisher unveröffentlichte Aufnahmen von Friedrich Gulda, die zwischen 1950 und 1959 entstanden. Die Einspielungen von Beethoven, Debussy, Ravel und Chopin zeigen den jungen Pianisten an der Schwelle zu internationalem Ruhm. Die Meinung unserer Musikkritiker: Eine repräsentative Auswahl bisher unveröffentlichter Aufnahmen, die aber bereits alle Namen enthält, die für Guldas späteres Repertoire bedeutend werden sollten: Mozart, Beethoven, Debussy, Ravel, Chopin. -

Jerusalem Quartet

The 2019/20 Beethoven Festival Opening Weekend BOOKING DETAILS ENCLOSED JERUSALEM QUARTET BARTÓK EXPLORED THE JERUSALEM QUARTET INTERVIEW SIMON MAJARO MBE SPRING SPECIAL CELEBRATION EMANUEL AX TURNS 70 2019 FRIENDS OF OF FRIENDS INSERT 2019/20 HIGHLIGHTS Beethoven was born in Bonn in December 1770. Throughout the 2019/20 Season, we will celebrate the 250th anniversary of his birth with a festival encompassing almost all of his instrumental and chamber repertoire and, through our Learning department, the influence of his legacy. Given Beethoven’s hearing loss later in times and we are delighted to introduce her life, in the 2019/20 Season we will have to the Wigmore Hall audience in March. Your the opportunity to examine how we listen exceptional financial support enables us to to music individually either as performers, present debut concerts such as this. It also composers or audience members. Included allows us to celebrate significant milestones with this issue of The Score magazine are with established artists such as Emmanuel the details for the exciting opening weekend Ax, in special gala events. celebrations on the 14 and 15 September We are delighted to announce that Kikkas © Kaupo when we present ten concerts in two days, Wigmore Hall is to become the new home placing Beethoven in context through the for CAVATINA’s extraordinary activities ABOVE John Gilhooly works of his predecessors and successors, nationwide. For those of you who don’t and those in the 20th century, and even already know CAVATINA and the story of its In this edition, there is also a very today, who still felt his influence. -

Fall/Winter 2002/2003

PRELUDE, FUGUE News for Friends of Leonard Bernstein RIFFS Fall/ Winter 2002 Bernstein's Mahler: A Personal View @ by Sedgwick Clark n idway through the Adagio £male of Mahler's Ninth M Symphony, the music sub sides from an almost desperate turbulence. Questioning wisps of melody wander throughout the woodwinds, accompanied by mut tering lower strings and a halting harp ostinato. Then, suddenly, the orchestra "vehemently burst[s] out" fortissimo in a final attempt at salvation. Most conductors impart a noble arch and beauty of tone to the music as it rises to its climax, which Leonard Bernstein did in his Vienna Philharmonic video recording in March 1971. But only seven months before, with the New York Philharmonic, His vision of the music is neither Nearly all of the Columbia cycle he had lunged toward the cellos comfortable nor predictable. (now on Sony Classical), taped with a growl and a violent stomp Throughout that live performance I between 1960 and 1974, and all of on the podium, and the orchestra had been struck by how much the 1980s cycle for Deutsche had responded with a ferocity I more searching and spontaneous it Grammophon, are handily gath had never heard before, or since, in was than his 1965 recording with ered in space-saving, budget-priced this work. I remember thinking, as the orchestra. Bernstein's Mahler sets. Some, but not all, of the indi Bernstein tightened the tempo was to take me by surprise in con vidual releases have survived the unmercifully, "Take it easy. Not so cert many times - though not deletion hammerschlag. -

2018–2019 Annual Report

18|19 Annual Report Contents 2 62 From the Chairman of the Board Ensemble Connect 4 66 From the Executive and Artistic Director Digital Initiatives 6 68 Board of Trustees Donors 8 96 2018–2019 Concert Season Treasurer’s Review 36 97 Carnegie Hall Citywide Consolidated Balance Sheet 38 98 Map of Carnegie Hall Programs Administrative Staff Photos: Harding by Fadi Kheir, (front cover) 40 101 Weill Music Institute Music Ambassadors Live from Here 56 Front cover photo: Béla Fleck, Edgar Meyer, by Stephanie Berger. Stephanie by Chris “Critter” Eldridge, and Chris Thile National Youth Ensembles in Live from Here March 9 Daniel Harding and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra February 14 From the Chairman of the Board Dear Friends, In the 12 months since the last publication of this annual report, we have mourned the passing, but equally importantly, celebrated the lives of six beloved trustees who served Carnegie Hall over the years with the utmost grace, dedication, and It is my great pleasure to share with you Carnegie Hall’s 2018–2019 Annual Report. distinction. Last spring, we lost Charles M. Rosenthal, Senior Managing Director at First Manhattan and a longtime advocate of These pages detail the historic work that has been made possible by your support, Carnegie Hall. Charles was elected to the board in 2012, sharing his considerable financial expertise and bringing a deep love and further emphasize the extraordinary progress made by this institution to of music and an unstinting commitment to helping the aspiring young musicians of Ensemble Connect realize their potential. extend the reach of our artistic, education, and social impact programs far beyond In August 2019, Kenneth J. -

Program Note to File

Abstract Title of Dissertation : Dance Based Music on Piano You Sang Kim, Doctor of Musical Art, 2015 Dissertation dirented by: Professor Larissa Dedova School of Music, Piano Division According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, the definition of dance is “to move your body in a way that goes with the rhythm and style of music that is being played.” 1 As you can see in that definition, these two important ways of expressing human feelings, music and dance, are very closely related. Countless pieces of music have been composed for dance, and are still being composed. It is impossible and useless to count how many kinds of dances exist in the world. Different kinds of dances have been developed according to their purposes, cultures, 1 Merriam-Webster Dictionary. “Dance.” http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/dance rhythm and tempo. For this reason, the field of dance-related music necessarily expanded significantly. A great deal of dance music has been written for orchestras, small ensembles, or vocals. Along with them, keyboard music also has a huge repertoire of dance pieces. For example, one of the most famous form in Baroque period was suites. Suites usually include 5 or more dance movements in the same key, such as Minuet, Allemende, Courant, Sarabande, Gigue, Bourree, Gavotte, Passepied, and so on. Nationalistic dances like waltz, polonaise, mazurka, and tarantella, were wonderful sources for composers like Chopin, Brahms, and Tchaikovsky. Dance-based movements were used for Mozart and Beethoven’s piano sonatas, chamber works and concertos. Composers have routinely traveled around the world to collect folk and dance tunes from places they visit.