OWN BRAND Many Great Composers Are Decent Pianists, but Great Pianists Who Write Substantially for Themselves to Perform Tend to Be Taken Less Seriously As Composers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rezension Für: Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin

Rezension für: Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin Edition Friedrich Gulda – The early RIAS recordings Ludwig van Beethoven | Claude Debussy | Maurice Ravel | Frédéric Chopin | Sergei Prokofiev | Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart 4CD aud 21.404 Radio Stephansdom CD des Tages, 04.09.2009 ( - 2009.09.04) Aufnahmen, die zwischen 1950 und 1959 entstanden. Glasklar, "gespitzter Ton" und... Full review text restrained for copyright reasons. Neue Musikzeitung 9/2009 (Andreas Kolb - 2009.09.01) Konzertprogramm im Wandel Konzertprogramm im Wandel Full review text restrained for copyright reasons. Piano News September/Oktober 2009, 5/2009 (Carsten Dürer - 2009.09.01) Friedrich Guldas frühe RIAS-Aufnahmen Friedrich Guldas frühe RIAS-Aufnahmen Full review text restrained for copyright reasons. page 1 / 388 »audite« Ludger Böckenhoff • Tel.: +49 (0)5231-870320 • Fax: +49 (0)5231-870321 • [email protected] • www.audite.de DeutschlandRadio Kultur - Radiofeuilleton CD der Woche, 14.09.2009 (Wilfried Bestehorn, Oliver Schwesig - 2009.09.14) In einem Gemeinschaftsprojekt zwischen dem Label "audite" und Deutschlandradio Kultur werden seit Jahren einmalige Aufnahmen aus den RIAS-Archiven auf CD herausgebracht. Inzwischen sind bereits 40 CD's erschienen mit Aufnahmen von Furtwängler und Fricsay, von Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau u. v. a. Die jüngste Produktion dieser Reihe "The Early RIAS-Recordings" enthält bisher unveröffentlichte Aufnahmen von Friedrich Gulda, die zwischen 1950 und 1959 entstanden. Die Einspielungen von Beethoven, Debussy, Ravel und Chopin zeigen den jungen Pianisten an der Schwelle zu internationalem Ruhm. Die Meinung unserer Musikkritiker: Eine repräsentative Auswahl bisher unveröffentlichter Aufnahmen, die aber bereits alle Namen enthält, die für Guldas späteres Repertoire bedeutend werden sollten: Mozart, Beethoven, Debussy, Ravel, Chopin. -

Interpreting Tempo and Rubato in Chopin's Music

Interpreting tempo and rubato in Chopin’s music: A matter of tradition or individual style? Li-San Ting A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales School of the Arts and Media Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences June 2013 ABSTRACT The main goal of this thesis is to gain a greater understanding of Chopin performance and interpretation, particularly in relation to tempo and rubato. This thesis is a comparative study between pianists who are associated with the Chopin tradition, primarily the Polish pianists of the early twentieth century, along with French pianists who are connected to Chopin via pedagogical lineage, and several modern pianists playing on period instruments. Through a detailed analysis of tempo and rubato in selected recordings, this thesis will explore the notions of tradition and individuality in Chopin playing, based on principles of pianism and pedagogy that emerge in Chopin’s writings, his composition, and his students’ accounts. Many pianists and teachers assume that a tradition in playing Chopin exists but the basis for this notion is often not made clear. Certain pianists are considered part of the Chopin tradition because of their indirect pedagogical connection to Chopin. I will investigate claims about tradition in Chopin playing in relation to tempo and rubato and highlight similarities and differences in the playing of pianists of the same or different nationality, pedagogical line or era. I will reveal how the literature on Chopin’s principles regarding tempo and rubato relates to any common or unique traits found in selected recordings. -

Chopin: Poet of the Piano

GOING BEHIND THE NOTES: EXPLORING THE GREAT PIANO COMPOSERS AN 8-PART LECTURE CONCERT SERIES CHOPIN: POET OF THE PIANO Dr. George Fee www.dersnah-fee.com Performance: Nocturne in E Minor, Op. 72, No. 1 (Op. Posth.) Introduction Early Life Performance: Polonaise in G minor (1817) Paris and the Polish Community in Paris Performance: Mazurkas in G-sharp Minor and B Minor, Op. 33, Nos. 1 and 4 Scherzo in C-sharp Minor, Op. 39 The Man Chopin (1810-1849) Parisian Society and Chopin as Teacher Chopin’s Performing and More on his Personality Performance: Waltz in A-flat Major, Op. 42 10 MINUTE BREAK Chopin’s Playing Performance: Nocturne in D-flat Major, Op. 27, No. 2 Chopin’s Music Performance: Mazurka in C-sharp Minor, Op. 50, No. 3 Chopin’s Teaching and Playing Chopin Today Chopin’s Relationship with Aurore Dupin (George Sand) Final Years Performance: Mazurka in F Minor, Op .68 No.4 Polonaise in A-flat Major Op. 53 READING ON CHOPIN Atwood, William G. The Parisian Worlds of Frédéric Chopin. Yale University Press, 1999. Eigeldinger, Jean-Jacques. Chopin: pianist and teacher as seen by his pupils. Cambridge University Press, 1986. Marek, George R. Chopin. Harper and Row, 1978. Methuen-Campbell, James. Chopin Playing: From the Composer to the Present Day. Taplinger Publishing Co., 1981. Siepmann, Jeremy. Chopin: The Reluctant Romanic. Victor Gollancz, 1995. Szulc, Tad. Chopin in Paris: The Life and Times of the Romantic Composer. Da Capo Press, 1998. Walker, Alan. Fryderyk Chopin: A Life and Times. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2018. -

Review of “22 Chopin Studies” by Leopold Godowsky by OPUS KLASSIEK , Published on 25 February 2013

Review of “22 Chopin Studies” by Leopold Godowsky by OPUS KLASSIEK , published on 25 February 2013 Leopold Godowsky (Zasliai, Litouwen 1870 - New York 1938) was sailing with the tide around 1900: the artistic and culturally rich turn of the century was a golden age for pianists. They were given plenty of opportunities to expose their pianistic and composing virtuosity (if they didn't demand the opportunities outright), both on concert stages as well as in the many music salons of the wealthy. Think about such giants as Anton Rubinstein, Jan Paderewski, Josef Hoffmann, Theodor Leschetizky, Vladimir Horowitz, Sergei Rachmaninoff, Ferruccio Busoni and Ignaz Friedman. The era of that other great piano virtuoso, Franz Liszt, was actually not even properly past. Liszt, after all, only returned from his last, very successful, but long and exhausting concert tour in the summer of 1886. The tour, through England and France, most likely did him in. (He died shortly afterwards, on the 31st of July 1886, at the age of seventy-four). Leopold Godowsky Godowsky's contemporaries called him the 'Buddha' of the piano, and he left a legacy of more than four hundred compositions, which make it crystal-clear that he knew the piano inside and out. Even more impressive, he shows in his compositions that as far as the technique of playing he had more mastery than his great contemporary Rachmaninoff, which clearly means something! It was by the way the very same Rachmaninoff who saw in Godowsky the only musician that made a lasting contribution to the development of the piano. -

Professor Doctor FRIEDRICH GULDA Called to the Waiter, Member to Qualify for the Final Eliminations

DOWN BEAT, august 1966 VIENNESE COOKING written by Willis Conover Professor Doctor FRIEDRICH GULDA called to the waiter, member to qualify for the final eliminations. Then he'd have to "Dry martini!'' The waiter, thinking he said "Drei martini|'' go through it all again. brought three drinks. It's the only time Gulda's wishes have The jurors were altoist Cannonball Adderley, trombonist J. J. ever been unclear or unsatisfied. Johnson, fluegelhornist Art Farmer, pianist Joe Zawinul, The whole city of Vienna, Austria snapped to attention when drummer Mel Lewis and bassist Ron Carter. The jury Gulda, the local Leonard Bernstein decided to run an chairman who wouldn't vote except in a tie, was critic Roman international competition for modern jazz. Waschko. The jury's refreshments were mineral water, king- For patrons he got the Minister of Foreign Affair, the Minister size cokes, and Viennese coffee. For three days that was all of Education, the Lord Mayor of Vienna and the they drank from 9:30 am till early evening. The jury took la Amtsfuhrender fur Kultur, Volksbildung und Schulverwaltung duties seriously. der Bundeshauptstadt Wien. For his committee of honor he A dialog across the screen might go like this. enlisted the diplomatic representatives of 20 countries, the Young lady in the organization (escorting contestant): "Mr. directors of 28 music organizations, and Duke Ellington. For Watschko?" expenses he obtained an estimated $80,000. For contestants Watschko: "Yes?" he got close to 100 young jazz musicians from 19 countries- Young lady: "Candidate No. 14 " some as distant as Uruguay and Brazil. -

Giovanni Sollima Violoncello Enrico Maria Baroni Clarinetto

Stagione 2019-2020 osn.rai.it Auditorium Rai “Arturo Toscanini”, Torino 1 1 Venerdì 11 ottobre 2019, 20.00 11–12/10 Sabato 12 ottobre 2019, 20.30 ConcertoJAMES diCONLON Carnevale direttore FUORIMARIANGELA ABBONAMENTO VACATELLO pianoforte ROBERTO RANFALDI violino Venerdì 21 febbraio 2020, 20.30 JOHNBeethoven AXELROD direttore GIOVANNIMendelssohn-Bartholdy SOLLIMA violoncello ENRICOŠostakovič MARIA BARONI clarinetto Bernstein Offenbach Ellington Gulda Gershwin CONCERTO DI CARNEVALE VENERDÌ 21 FEBBRAIO 2020 ore 20.30 John Axelrod direttore Giovanni Sollima violoncello Enrico Maria Baroni clarinetto Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) Prelude, fugue and riffs, per clarinetto e jazz ensemble (1949-1952) Prelude for the Brass - Fugue for the Saxes - Riffs for Everyone Durata: 10’ ca. Ultima esecuzione Rai a Torino: 30 novembre 2012 William Eddins, Enrico Maria Baroni. Friedrich Gulda (1930-2000) Concerto per violoncello, fiati e batteria (1980) Ouverture Idylle Cadenza Minuetto Finale. Alla marcia Durata: 32’ ca. Ultima esecuzione Rai a Torino: 11 novembre 2011 Gürer Aykal, Massimo Macrì Jacques Offenbach (1819-1880) Etude n. 11 da 12 Etudes op. 78 per violoncello solo (1855) Durata: 3’ ca. __________ George Gershwin (1898-1937) Cuban Overture (1932) Il concerto Durata: 10’ ca. è trasmesso in diretta su Radio3 Prima esecuzione Rai a Torino per Il Cartellone di Radio3 Suite. Duke Ellington (1899-1974) Harlem (1950) (orchestrazione di Luther Henderson) Nella foto Concerto del pianista Durata: 20’ ca. e compositore Friedrich Gulda - Ultima esecuzione Rai a Torino: Milano, 1962 20 maggio 2011 William Eddins New York Follies «New York aveva tutta l’iridescenza del principio del mondo», scrive Francis Scott Fitzgerald inL’età del jazz, ricordando il suo incontro con la metropoli all’inizio degli anni Venti. -

A YEAR of TOURING H ARTUR RUBINSTEIN ANTWERP, BELGIUM BRUSSELS

<; :■ ARTUR RUBINSTEIN Exclusive Management: HUROK ARTISTS, Inc. 711 Fifth Avenue, New York 22, N. Y. ARTUR RUBINSTEIN ‘THE MAN AND HIS MUSIC ENRICH THE LIVES OF PEOPLE EVERYWHERE' By HOWARD TAUBMAN Music Editor of the New York Times \ rtur Rubinstein is a complete artist because as an artist and admired as a man all over the Ahe is a whole man. It does not matter whether world. In his decades as a public performer he /—\ those who go to his concerts are ear-minded has appeared, it has been estimated, in every or eye-minded — or both. His performances are country except Tibet. He has not played in Ger a comfort to, and an enlargement of, all the many since the First World War, but that is faculties in the audience. And he has the choice because of his own choice. He felt then that the gift of being able to convey musical satisfaction Germans had forfeited a large measure of their —even exaltation—to all conditions of listeners right to be regarded as civilized, and he saw from the most highly trained experts to the most nothing in the agonized years of the Thirties and innocent of laymen. Forties which would cause him to change his mind about Germany. The reason for this is that you cannot separate Artur Rubinstein the man from Artur Rubinstein The breadth of Rubinstein's sympathies are in the musician. Man and musician are indivisible, escapable in the concert hall. He plays music of as they must be in all truly great and integrated all periods and lands, and to each he gives its due. -

S Twenty-Fourth Caprice, Op. 1 by Busoni, Friedman, and Muczynski

AN ANALYTICAL STUDY OF THE VARIATIONS ON THE THEME OF PAGANINI’S TWENTY-FOURTH CAPRICE, OP. 1 BY BUSONI, FRIEDMAN, AND MUCZYNSKI, A LECTURE RECITAL, TOGETHER WITH THREE RECITALS OF SELECTED WORKS BY BACH, BEETHOVEN, CHOPIN, DEBUSSY, HINDEMITH, KODÁLY, PROKOFIEV, SCRIABIN, AND SILOTI Kwang Sun Ahn, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2000 APPROVED: Joseph Banowetz, Major Professor Gene J. Cho, Minor Professor Steven Harlos, Committee Member Adam J. Wodnicki, Committee Member William V. May, Dean of the College of Music C. Neal Tate, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Ahn, Kwang Sun, An Analytical Study of the Variations on the Theme of Paganini’s Twenty-fourth Caprice, Op. 1 by Busoni, Friedman, and Muczynski. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2000, 94 pp., 66 examples, 9 tables, bibliography, 71 titles. The purpose of this study is to analyze sets of variations on Paganini’s theme by three twentieth-century composers: Ferruccio Busoni, Ignaz Friedman, and Robert Muczynski, in order to examine, identify, and trace different variation techniques and their applications. Chapter 1 presents the purpose and scope of this study. Chapter 2 provides background information on the musical form “theme and variations” and the theme of Paganini’s Twenty-fourth Caprice, Op. 1. Chapter 2 also deals with the question of which elements have made this theme so popular. Chapters 3,4, and 5 examine each of the three sets of variations in detail using the following format: theme, structure of each variation, harmony and key, rhythm and meter, tempo and dynamics, motivic development, grouping of variations, and technical problems. -

Decca - Wiener Philharmoniker

DECCA - WIENER PHILHARMONIKER Vienna Holiday, Hans Knappertsbusch New Year Concert 1951, Hilde Gueden (soprano), Clemens Krauss, Josef Krips Overtures of Old Vienna, Willi Boskovsky New Year Concert 1979, Willi Boskovsky Adam: Giselle, Herbert von Karajan Bartók: Two Portraits Op. 5, The Miraculous Mandarin, Op. 19, Sz. 73 (complete ballet), Erich Binder (violin), Christoph von Dohnányi Beethoven: Symphony No. 1 in C major, Op. 21, Pierre Monteux Beethoven: Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 36, Hans Schmidt-Isserstedt Beethoven: Symphony No. 4 in B flat major, Op. 60, Hans Schmidt-Isserstedt Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 in E flat major, Op. 55 'Eroica', Erich Kleiber Beethoven: Leonore Overture No. 2, Op. 72a, Leonore Overture No. 3, Op. 72b, Erich Kleiber Beethoven: Fidelio Overture Op. 72c, Clemens Krauss Beethoven: Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67, Sir Georg Solti, Beethoven: Symphony No. 7 in A major, Op. 92,. Sir Georg Solti Beethoven: Symphony No. 8 in F major, Op. 93, Claudio Abbado Beethoven: Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125 'Choral', Joan Sutherland (soprano), Marilyn Horne (contralto), James King (tenor), Martti Talvela (bass), Hans Schmidt- Isserstedt Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 1 in C Major, Op. 15, Friedrich Gulda (piano), Karl Böhm Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 2 in B flat major, Op. 19, Vladimir Ashkenazy (piano), Zubin Mehta Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 3 in C minor, Op. 37, Friedrich Gulda (piano), Horst Stein Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 4 in G major, Op. 58, Friedrich Gulda (piano), Horst Stein Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 5 in E flat major, Op. 73 'Emperor', Clifford Curzon (piano), Hans Knappertsbusch Beethoven: String Quartet No. -

Jansen/Maisky/ Argerich Trio Tuesday 6 February 2018 7.30Pm, Hall

Jansen/Maisky/ Argerich Trio Tuesday 6 February 2018 7.30pm, Hall Beethoven Cello Sonata in G minor, Op 5 No 2 Shostakovich Piano Trio No 2 in E minor, Op 67 interval 20 minutes Schumann Violin Sonata No 1 in A minor, Op 105 Mendelssohn Piano Trio No 1 in D minor, Op 49 Janine Jansen violin Mischa Maisky cello Martha Argerich piano Adriano Heitman Adriano Part of Barbican Presents 2017–18 Programme produced by Harriet Smith; printed by Trade Winds Colour Printers Ltd; advertising by Cabbell (tel. 020 3603 7930) Confectionery and merchandise including organic ice cream, quality chocolate, nuts and nibbles are available from the sales points in our foyers. Please turn off watch alarms, phones, pagers etc during the performance. Taking photographs, capturing images or using recording devices during a performance is strictly prohibited. If anything limits your enjoyment please let us know The City of London during your visit. Additional feedback can be given Corporation is the founder and online, as well as via feedback forms or the pods principal funder of located around the foyers. the Barbican Centre Welcome Tonight we are delighted to welcome three friend Ivan Sollertinsky, an extraordinarily musicians so celebrated that they need no gifted man in many different fields. introduction. Martha Argerich and Mischa Maisky have been performing together We begin with Beethoven, and his Second for more than four decades, while Janine Cello Sonata, a work that is groundbreaking Jansen is a star of the younger generation. for treating string instrument and piano equally and which ranges from sheer Together they present two vastly different wit to high drama. -

Steinway Society 17-18 Program

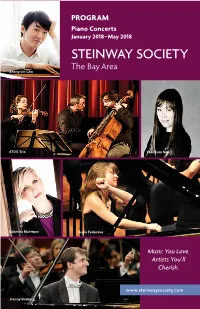

PROGRAM Piano Concerts January 2018–May 2018 Steinway Society The Bay Area Seong-Jin Cho ATOS Trio Yeol Eum Son Gabriela Martinez Anna Fedorova Music You Love. Artists You’ll Cherish. www.steinwaysociety.com Kenny Broberg Steinway Society - The Bay Area Letter from the President Depends Upon Your Support Dear Patron, Steinway Society – The Bay Area is led by volunteers who love piano and In his book, What Makes It Great: Short Masterpieces, classical music, and we are always looking for like-minded people. Here Great Composers, conductor Rob Kapilow asks what are a few ways you can help bring international concert pianists, in- makes a piece of classical music great. His answer: school educational experiences, master classes, and student performance memorable melody, rich harmonies, addictive opportunities to our community. rhythm, influence on other composers, and the work’s role in one’s life. Buy a Season or Series-4 Subscription Your subscription provides extended support while giving you the gift of Steinway Society is honored to present great music, works created beautiful music. over the centuries, performed by international artists who grace these works with sublime interpretation and dramatic virtuosity. Become a Donor Ticket sales cover only about 60% of our costs. Your gifts are crucial for Our season’s second half features six artists judged “best” by everything we do, and are greatly appreciated. Please consider a legacy prestigious international competitions, by key critics and by gift such as a recital series in your name that will help continue bringing enthusiastic audiences. In January 2018, Cliburn Silver Medalist magnificent classical music to future generations. -

Download Booklet

110690 bk Friedman3 EC 5|12|02 3:35 PM Page 5 Ignaz Friedman 8 Mazurka, Op. 7, No. 2 in A minor 2:30 Appendix: ADD Complete Recordings, Volume 3 ( Friedman speaks on Chopin 5:11 English Columbia 1928-1930 9 Mazurka, Op. 33, No. 2 in D major 2:04 Recorded November 1940 Great Pianists • Friedman 8.110690 Recorded 13th September 1930 New Zealand Radio transcription disc 1928 Matrix 5211-5 (Catalogue LX99) Gluck/Brahms: Discographic information taken from 1 Gavotte 2:47 0 Mazurka, Op. 33, No. 4 in B minor 4:08 “Ignaz Friedman: A Discography, Part 1”, Recorded 9th February 1928 Recorded 13th September 1930 compiled by D.H. Mason and Gregor Benko. CHOPIN Matrix WA6943-1 (Catalogue D1651) Matrix 5209-5 (Catalogue LX100) Please thank: Donald Manildi and Gluck/Friedman: ! Mazurka, Op. 24, No. 4 in B flat major 3:44 Raymond Edwards. Mazurkas 2 Menuet (Judgement of Paris) 2:55 Recorded 13th September 1930 Recorded 10th February 1928 Matrix 5208-6 (Catalogue LX100) Polonaise in B flat Matrix WA6945-2 (Catalogue D1640) @ Mazurka, Op. 41, No. 1 in C sharp minor 3:02 Schubert/Liszt: Recorded 10th October 1929 3 Hark, hark, the lark 2:55 Matrix 5207-2 Recorded 10th February 1928 (issued only in U.S. Catalogue 67950) SCHUBERT Matrix WA6947-1 (Catalogue D1636) # Mazurka, Op. 41, No. 1 in C sharp minor 3:00 Hark, hark the lark Schubert/Friedman: Recorded 17th September 1930 4 Alt Wien 7:08 Matrix 5207-9 (Catalogue LX101) Recorded 2nd March 1928 Alt Wien Matrix WAX3341-1, 3342-2 (Catalogue L2107) $ Mazurka, Op.