***MARCH 2012** Revised LSE PHD W Minor Corrections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Muslim Nationalism, State Formation and Legal Representations of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan

Politics of Exclusion: Muslim Nationalism, State Formation and Legal Representations of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan by Sadia Saeed A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Sociology) in The University of Michigan 2010 Doctoral Committee: Professor George P. Steinmetz, Chair Professor Howard A. Kimeldorf Associate Professor Fatma Muge Gocek Associate Professor Genevieve Zubrzycki Professor Mamadou Diouf, Columbia University © Sadia Saeed 2010 2 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my parents with my deepest love, respect and gratitude for the innumerable ways they have supported my work and choices. ii Acknowledgements I would like to begin by acknowledging the immense support my parents have given me every step of the way during my (near) decade in graduate school. I have dedicated this dissertation to them. My ammi and baba have always believed in my capabilities to accomplish not only this dissertation but much more in life and their words of love and encouragement have continuously given me the strength and the will to give my research my very best. My father‘s great enthusiasm for this project, his intellectual input and his practical help and advice during the fieldwork of this project have been formative to this project. I would like to thank my dissertation advisor George Steinmetz for the many engaged conversations about theory and methods, for always pushing me to take my work to the next level and above all for teaching me to recognize and avoid sloppiness, caricatures and short-cuts. It is to him that I owe my greatest intellectual debt. -

Political Development, the People's Party of Pakistan and the Elections of 1970

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1973 Political development, the People's Party of Pakistan and the elections of 1970. Meenakshi Gopinath University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Gopinath, Meenakshi, "Political development, the People's Party of Pakistan and the elections of 1970." (1973). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2461. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/2461 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FIVE COLLEGE DEPOSITORY POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT, THE PEOPLE'S PARTY OF PAKISTAN AND THE ELECTIONS OF 1970 A Thesis Presented By Meenakshi Gopinath Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS June 1973 Political Science POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT, THE PEOPLE'S PARTY OF PAKISTAN AND THE ELECTIONS OF 1970 A Thesis Presented By Meenakshi Gopinath Approved as to style and content hy: Prof. Anwar Syed (Chairman of Committee) f. Glen Gordon (Head of Department) Prof. Fred A. Kramer (Member) June 1973 ACKNOWLEDGMENT My deepest gratitude is extended to my adviser, Professor Anwar Syed, who initiated in me an interest in Pakistani poli- tics. Working with such a dedicated educator and academician was, for me, a totally enriching experience. I wish to ex- press my sincere appreciation for his invaluable suggestions, understanding and encouragement and for synthesizing so beautifully the roles of Friend, Philosopher and Guide. -

![South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 22 | 2019, “Student Politics in South Asia” [Online], Online Since 15 December 2019, Connection on 24 March 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0491/south-asia-multidisciplinary-academic-journal-22-2019-student-politics-in-south-asia-online-online-since-15-december-2019-connection-on-24-march-2021-510491.webp)

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 22 | 2019, “Student Politics in South Asia” [Online], Online Since 15 December 2019, Connection on 24 March 2021

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal 22 | 2019 Student Politics in South Asia Jean-Thomas Martelli and Kristina Garalyté (dir.) Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/samaj/5852 DOI: 10.4000/samaj.5852 ISSN: 1960-6060 Publisher Association pour la recherche sur l'Asie du Sud (ARAS) Electronic reference Jean-Thomas Martelli and Kristina Garalyté (dir.), South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal, 22 | 2019, “Student Politics in South Asia” [Online], Online since 15 December 2019, connection on 24 March 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/samaj/5852; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/samaj. 5852 This text was automatically generated on 24 March 2021. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Generational Communities: Student Activism and the Politics of Becoming in South Asia Jean-Thomas Martelli and Kristina Garalytė Student Politics in British India and Beyond: The Rise and Fragmentation of the All India Student Federation (AISF), 1936–1950 Tom Wilkinson A Campus in Context: East Pakistan’s “Mass Upsurge” at Local, Regional, and International Scales Samantha Christiansen Crisis of the “Nehruvian Consensus” or Pluralization of Indian Politics? Aligarh Muslim University and the Demand for Minority Status Laurence Gautier Patronage, Populism, and Protest: Student Politics in Pakistani Punjab Hassan Javid The Spillovers of Competition: Value-based Activism and Political Cross-fertilization in an Indian Campus Jean-Thomas Martelli Regional Charisma: The Making of a Student Leader in a Himalayan Hill Town Leah Koskimaki Performing the Party. National Holiday Events and Politics at a Public University Campus in Bangladesh Mascha Schulz Symbolic Boundaries and Moral Demands of Dalit Student Activism Kristina Garalytė How Campuses Mediate a Nationwide Upsurge against India’s Communalization. -

A Stranger in My Own Country East Pakistan 1969-1974

A Stranger in Ny Own Contry East Pakistan, 1969-1971 repreoduced by Sani H. Panhwar A Stra nger inm yow n c ountry Ea stPa kista n, 1969-1971 Ma jor Genera l (Retd) Kha dim Hussa inRa ja Reproducedb y Sa niH. Pa nhw a r C O N TEN TS Introduction By Muhammad Reza Kazimi .. .. .. .. .. 1 Chapter 1 The Brewing Storm .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 6 Chapter 2 Prelude to the 1970 Elections .. .. .. .. .. .. 13 Chapter 3 The Rising Sun of the Awami League .. .. .. .. .. 22 Chapter 4 The Devastating Cyclone of November 1970 .. .. .. .. 26 Chapter 5 A No-Win Situation .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 28 Chapter 6 The Crisis Deepens .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 32 Chapter 7 Lt. Gen. Tikka Khan in Action .. .. .. .. .. .. 42 Chapter 8 Operation Searchlight .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 50 Chapter 9 Last Words . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 63 Appendix A .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 70 Appendix B .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 71 Appendix C .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 78 Introduction B y M uham m adReza Kazim i History, it is often said, 'is written by victors'. In the case of East Pakistan, it has been written by the losers. One general,1 one lieutenant general,2 four major generals,3 and two brigadiers4 have given their account of the events leading to the secession of East Pakistan. Some of their compatriots, who witnessed or participated in the event, are still reluctant to publish their impressions. The credibility of such accounts depends on whether they were written for self-justification or for introspection. The utility of such accounts depends on whether they are relevant. On both counts, these recollections of the late Major General Khadim Hussain Raja are of definite value. They are candid and revealing; they are also imbued with respect for the opposite point of view. -

Who Is Who in Pakistan & Who Is Who in the World Study Material

1 Who is Who in Pakistan Lists of Government Officials (former & current) Governor Generals of Pakistan: Sr. # Name Assumed Office Left Office 1 Muhammad Ali Jinnah 15 August 1947 11 September 1948 (died in office) 2 Sir Khawaja Nazimuddin September 1948 October 1951 3 Sir Ghulam Muhammad October 1951 August 1955 4 Iskander Mirza August 1955 (Acting) March 1956 October 1955 (full-time) First Cabinet of Pakistan: Pakistan came into being on August 14, 1947. Its first Governor General was Muhammad Ali Jinnah and First Prime Minister was Liaqat Ali Khan. Following is the list of the first cabinet of Pakistan. Sr. Name of Minister Ministry 1. Liaqat Ali Khan Prime Minister, Foreign Minister, Defence Minister, Minister for Commonwealth relations 2. Malik Ghulam Muhammad Finance Minister 3. Ibrahim Ismail Chundrigar Minister of trade , Industries & Construction 4. *Raja Ghuzanfar Ali Minister for Food, Agriculture, and Health 5. Sardar Abdul Rab Nishtar Transport, Communication Minister 6. Fazal-ul-Rehman Minister Interior, Education, and Information 7. Jogendra Nath Mandal Minister for Law & Labour *Raja Ghuzanfar’s portfolio was changed to Minister of Evacuee and Refugee Rehabilitation and the ministry for food and agriculture was given to Abdul Satar Pirzada • The first Chief Minister of Punjab was Nawab Iftikhar. • The first Chief Minister of NWFP was Abdul Qayum Khan. • The First Chief Minister of Sindh was Muhamad Ayub Khuro. • The First Chief Minister of Balochistan was Ataullah Mengal (1 May 1972), Balochistan acquired the status of the province in 1970. List of Former Prime Ministers of Pakistan 1. Liaquat Ali Khan (1896 – 1951) In Office: 14 August 1947 – 16 October 1951 2. -

Reimagining the Role of Mian Muhamad Mumtaz Daultana in Colonial and Post-Colonial Punjab

Journal of the Research Society of Pakistan Volume No. 57, Issue No. 1 (January – June, 2020) Farzanda Aslam * Muhamad Iqbal Chawla ** Zabir Saeed *** Moazzam Wasti **** Forgotten soldier of Pakistan Movement: Reimagining the role of Mian Muhamad Mumtaz Daultana in Colonial and Post-colonial Punjab Abstract Plethora of works have been produced on the colonial and post-colonial history of the Punjab but the role of Mian Muhammad Mumtaz Daultana has been academically overnighted by the historians to date and this paper intends to address it. He was an important leader of the Punjab who remained committed to the Pakistan movement, remained loyal and worked hard under the leadership of Quaid-i-Azam in the creation and consolidation of Pakistan. He was president of the Punjab Muslim League and also the first chief Minister of Pakistani Punjab. Therefore it is of immense importance to understand the role of Mian Muhammad Mumtaz Daultana in the creation and consolidation of Pakistan in the light of primary and secondary sources. Before the inception of Pakistan, his father Ahmad Yar Daultana was a popular politician from the Daultana family in the Punjab region. His house was the focal point for important political activities. Daultana was selected by Quaid-i- Azam to contend on behalf of the Muslim League against the Unionist Party because this party was not in favour of the Muslim League, by looking for the certainty of the Mumtaz Daultana, Quaid-i-Azam made him the individual from the member of Direct-action committee. The other member of the committee was ministers of the Muslim League s’ parliamentary and interim government. -

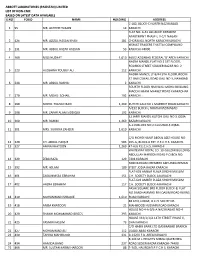

Abbott Laboratories (Pakistan) Limited List of Non-Cnic Based on Latest Data Available S.No Folio Name Holding Address 1 95

ABBOTT LABORATORIES (PAKISTAN) LIMITED LIST OF NON-CNIC BASED ON LATEST DATA AVAILABLE S.NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD 1 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN 14 KARACHI FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE APARTMENT PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN 2 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN 181 CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND 3 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN 53 KARACHI-74000. 4 169 MISS NUZHAT 1,610 469/2 AZIZABAD FEDERAL 'B' AREA KARACHI NAZRA MANZIL FLAT NO 2 1ST FLOOR, RODRICK STREET SOLDIER BAZAR NO. 2 5 223 HUSSAINA YOUSUF ALI 112 KARACHI NADIM MANZIL LY 8/44 5TH FLOOR, ROOM 37 HAJI ESMAIL ROAD GALI NO 3, NAYABAD 6 244 MR. ABDUL RASHID 2 KARACHI FOURTH FLOOR HAJI WALI MOHD BUILDING MACCHI MIANI MARKET ROAD KHARADHAR 7 270 MR. MOHD. SOHAIL 192 KARACHI 8 290 MOHD. YOUSUF BARI 1,269 KUTCHI GALI NO 1 MARRIOT ROAD KARACHI A/192 BLOCK-L NORTH NAZIMABAD 9 298 MR. ZAFAR ALAM SIDDIQUI 192 KARACHI 32 JAFRI MANZIL KUTCHI GALI NO 3 JODIA 10 300 MR. RAHIM 1,269 BAZAR KARACHI A-113 BLOCK NO 2 GULSHAD-E-IQBAL 11 301 MRS. SURRIYA ZAHEER 1,610 KARACHI C/O MOHD HANIF ABDUL AZIZ HOUSE NO. 12 320 CH. ABDUL HAQUE 583 265-G, BLOCK-6 EXT. P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI. 13 327 AMNA KHATOON 1,269 47-A/6 P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI WHITEWAY ROYAL CO. 10-GULZAR BUILDING ABDULLAH HAROON ROAD P.O.BOX NO. 14 329 ZEBA RAZA 129 7494 KARACHI NO8 MARIAM CHEMBER AKHUNDA REMAN 15 392 MR. -

The Other Battlefield Construction And

THE OTHER BATTLEFIELD – CONSTRUCTION AND REPRESENTATION OF THE PAKISTANI MILITARY ‘SELF’ IN THE FIELD OF MILITARY AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL NARRATIVE PRODUCTION Inauguraldissertation an der Philosophisch-historischen Fakultät der Universität Bern zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde vorgelegt von Manuel Uebersax Promotionsdatum: 20.10.2017 eingereicht bei Prof. Dr. Reinhard Schulze, Institut für Islamwissenschaft der Universität Bern und Prof. Dr. Jamal Malik, Institut für Islamwissenschaft der Universität Erfurt Originaldokument gespeichert auf dem Webserver der Universitätsbibliothek Bern Dieses Werk ist unter einem Creative Commons Namensnennung-Keine kommerzielle Nutzung-Keine Bearbeitung 2.5 Schweiz Lizenzvertrag lizenziert. Um die Lizenz anzusehen, gehen Sie bitte zu http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ch/ oder schicken Sie einen Brief an Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California 94105, USA. 1 Urheberrechtlicher Hinweis Dieses Dokument steht unter einer Lizenz der Creative Commons Namensnennung-Keine kommerzielle Nutzung-Keine Bearbeitung 2.5 Schweiz. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ch/ Sie dürfen: dieses Werk vervielfältigen, verbreiten und öffentlich zugänglich machen Zu den folgenden Bedingungen: Namensnennung. Sie müssen den Namen des Autors/Rechteinhabers in der von ihm festgelegten Weise nennen (wodurch aber nicht der Eindruck entstehen darf, Sie oder die Nutzung des Werkes durch Sie würden entlohnt). Keine kommerzielle Nutzung. Dieses Werk darf nicht für kommerzielle Zwecke verwendet werden. Keine Bearbeitung. Dieses Werk darf nicht bearbeitet oder in anderer Weise verändert werden. Im Falle einer Verbreitung müssen Sie anderen die Lizenzbedingungen, unter welche dieses Werk fällt, mitteilen. Jede der vorgenannten Bedingungen kann aufgehoben werden, sofern Sie die Einwilligung des Rechteinhabers dazu erhalten. Diese Lizenz lässt die Urheberpersönlichkeitsrechte nach Schweizer Recht unberührt. -

PRINT CULTURE and LEFT-WING RADICALISM in LAHORE, PAKISTAN, C.1947-1971

PRINT CULTURE AND LEFT-WING RADICALISM IN LAHORE, PAKISTAN, c.1947-1971 Irfan Waheed Usmani (M.Phil, History, University of Punjab, Lahore) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SOUTH ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAMME NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is my original work and it has been written by me in its entirety. I have duly acknowledged all the sources of information which have been used in the thesis. This thesis has also not been submitted for any degree in any university previously. _________________________________ Irfan Waheed Usmani 21 August 2015 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First I would like to thank God Almighty for enabling me to pursue my higher education and enabling me to finish this project. At the very outset I would like to express deepest gratitude and thanks to my supervisor, Dr. Gyanesh Kudaisya, who provided constant support and guidance to this doctoral project. His depth of knowledge on history and related concepts guided me in appropriate direction. His interventions were both timely and meaningful, contributing towards my own understanding of interrelated issues and the subject on one hand, and on the other hand, injecting my doctoral journey with immense vigour and spirit. Without his valuable guidance, support, understanding approach, wisdom and encouragement this thesis would not have been possible. His role as a guide has brought real improvements in my approach as researcher and I cannot measure his contributions in words. I must acknowledge that I owe all the responsibility of gaps and mistakes in my work. I am thankful to his wife Prof. -

3 Who Is Who and What Is What

3 e who is who and what is what Ever Success - General Knowledge 4 Saad Book Bank, Lahore Ever Success Revised and Updated GENERAL KNOWLEDGE Who is who? What is what? CSS, PCS, PMS, FPSC, ISSB Police, Banks, Wapda, Entry Tests and for all Competitive Exames and Interviews World Pakistan Science English Computer Geography Islamic Studies Subjectives + Objectives etc. Abbreviations Current Affair Sports + Games Ever Success - General Knowledge 5 Saad Book Bank, Lahore © ALL RIGHTS RESERVED No part of this book may be reproduced In any form, by photostate, electronic or mechanical, or any other means without the written permission of author and publisher. Composed By Muhammad Tahsin Ever Success - General Knowledge 6 Saad Book Bank, Lahore Dedicated To ME Ever Success - General Knowledge 7 Saad Book Bank, Lahore Ever Success - General Knowledge 8 Saad Book Bank, Lahore P R E F A C E I offer my services for designing this strategy of success. The material is evidence of my claim, which I had collected from various resources. I have written this book with an aim in my mind. I am sure this book will prove to be an invaluable asset for learners. I have tried my best to include all those topics which are important for all competitive exams and interviews. No book can be claimed as prefect except Holy Quran. So if you found any shortcoming or mistake, you should inform me, according to your suggestions, improvements will be made in next edition. The author would like to thank all readers and who gave me their valuable suggestions for the completion of this book. -

Pakistan's Historical Links with the Middle East in the 1970S

Syracuse University SURFACE Theses - ALL May 2019 From the Indian Ocean to the Persian: Pakistan's Historical Links with the Middle East in the 1970s Mohammad Ebad Athar Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/thesis Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Athar, Mohammad Ebad, "From the Indian Ocean to the Persian: Pakistan's Historical Links with the Middle East in the 1970s" (2019). Theses - ALL. 298. https://surface.syr.edu/thesis/298 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT “From the Indian Ocean to the Persian Gulf” assesses Pakistan’s connections to two of the Persian Gulf’s principal actors, Iran and Saudi Arabia from 1971 to 1977. In the aftermath of the 1971 Indo-Pak War, Islamabad began orienting its foreign policy toward the Gulf politically, economically, militarily, and religiously. These relationships in the 1970s established the foundation for Pakistan’s relations with the Gulf in the 1980s and subsequent decades. Utilizing Pakistani news media, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s speeches and statements, memoirs from Pakistani diplomats, and American archival material, I argue that understanding the ways in which Pakistan, Iran, and Saudi Arabia interacted with each other in this period helps to explain the cooperation seen during the Soviet war in Afghanistan and the Iran-Iraq War of the 1980s. Furthermore, this project sheds light on the importance of regional constructions to foreign policy interests. -

Disease and Death: Issues of Public Health Among East Bengali Refugees in 1971 -Utsa Sarmin

Disease and Death: Issues of Public Health Among East Bengali Refugees in 1971 -Utsa Sarmin Introduction: “Because of 'Operation Searchlight', 10 million refugees came to India, most of them living in appalling conditions in the refugee camps. I cannot forget seeing 10 children fight for one chapatti. I cannot forget the child queuing for milk, vomiting, collapsing and dying of cholera. I cannot forget the woman lying in the mud, groaning and giving birth.”1 The situation of East Bengali refugees in 1971 was grim. The Bangladesh liberation war of 1971 witnessed 10 million people from the erstwhile East Pakistan (present Bangladesh), fleeing the persecution by Pakistani soldiers and coming to India seeking refuge2. The sudden influx of refugees created a mammoth humanitarian crisis. At one hand, the refugees were struggling to access food, water, proper sanitation, shelter. On the other hand, their lives were tormented by various health issues. The cholera epidemic of 1971 alone killed over 5,000 refugees.3 Other health concerns were malnutrition, exhaustion, gastronomical diseases. “A randomized survey on refugee health highlights the chief medical challenges in the refugee population as being malnutrition, diarrhoea, vitamin-A deficiency, pyoderma, and tuberculosis.”4 The Indian government was not adequately equipped to deal with a crisis of such level. Even though there was initial sympathies with the refugees, it quickly waned and by May 1971, the then Prime Minister of India, Indira Gandhi characterized it as a “national problem”5 and by July, she described the problem could potentially threaten the peace of South Asia.6 The proposed research paper will look into the public health crisis and the rate of mortality due to the crisis among the refugees of West Bengal in 1971.