Bangladesh's Genocide Debate; a Conscientious Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Veer Naris of 1962 War

December 15, 2012 Volume VII, Issue 12 100/- or US $10 Asia Defence News Asia DefenceAsian News Defence Analyses. Every Month. December 15, 2012 Volume VII, Issue 12 VII, Issue Volume 100/- or US $10 100/- or Veer Naris Of 1962 War Pak On Tenterhooks Will Pakistan Change? 1971 Revisited Trial And Terror The Incredible Army Vets Gravity Of “Bangladeshi” Menace HE DOES THIS FOR YOU. AND WE REPORT HIS SACRIFICES. Reporters risking their lives at the borders News from the skies and the seas 5 languages 120 newspapers subscribing and growing Which other news agency will give you such in-depth coverage of Asian defence news? ADNI ASIA DEFENCE NEWS INTERNATIONAL THE NEWS AGENCY THAT BRINGS YOU DEFENCE SECURITY COVERAGE LIKE NO ONE ELSE www.asiadefenceinternational.com 10-03-12 • LEO BURNETT, (ASIA DEFENCE NEWS: Page Ad) • 12-1445-04-A-SIKORSKY-ADN-UTCIP113 BLEED: 210mm W X 270mm H •TRIM: 180mm W X 240mm H • ISSUE DATE: 10-12-2012 Sikorsky S-70B helicopter Security. One powerful idea. Battle-proven technology. State-of-the-art equipment. The S-70B protects above and below the water with anti-submarine / anti-surface mission solutions. Its array of fi eld-proven capabilities and mission-adaptive systems makes the S-70B the world’s most capable maritime helicopter. Sikorsky: a business unit of United Technologies. TEL: +91 11 40881000 Otis | Pratt & Whitney | Sikorsky | UTC Aerospace Systems | UTC Climate, Controls & Security Contents 24 Special Reports 24 The Malala Factor: Will Pakistan Change? By Cecil Victor 26 Imran Hits Nail On The Head By -

GOVT-PUNJAB Waitinglist Nphs.Pdf

WAITING LIST SUMMARY DATE & TIME 20-04-2021 02:21:11 PM BALLOT CATEGORY GOVT-PUNJAB TOTAL WAITING APPLICANTS 8711 WAITING LIST OF APPLICANTS S No. Receipt ID Applicant Name Father Name CNIC 1 27649520 SHABAN ALI MUHAMMAD ABBAS ADIL 3520106922295 2 27649658 Waseem Abbas Qalab Abbas 3520113383737 3 27650644 Usman Hiader Sajid Abbasi 3650156358657 4 27651140 Adil Baig Ghulam Sarwar 3520240247205 5 27652673 Nadeem Akhtar Muhammad Mumtaz 4220101849351 6 27653461 Imtiaz Hussain Zaidi Shasmshad Hussain Zaidi 3110116479593 7 27654564 Bilal Hussain Malik tasadduq Hussain 3640261377911 8 27658485 Zahid Nazir Nazir Ahmed 3540173750321 9 27659188 Muhammad Bashir Hussain Muhammad Siddique 3520219305241 10 27659190 IFTIKHAR KHAN SHER KHAN 3520226475101 ------------------- ------------------- ------------------- ------------------- Director Housing-XII (LDAC NPA) Director Finance Director IT (I&O) Chief Town Planner Note: This Ballot is conducted by PITB on request of DG LDA. PITB is not responsible for any data Anomalies. Ballot Type: GOVT-PUNJAB Date&time : Tuesday, Apr 20, 2021 02:21 PM Page 1 of 545 WAITING LIST OF APPLICANTS S No. Receipt ID Applicant Name Father Name CNIC 11 27659898 Maqbool Ahmad Muhammad Anar Khan 3440105267405 12 27660478 Imran Yasin Muhammad Yasin 3540219620181 13 27661528 MIAN AZIZ UR REHMAN MUHAMMAD ANWAR 3520225181377 14 27664375 HINA SHAHZAD MUHAMMAD SHAHZAD ARIF 3520240001944 15 27664446 SAIRA JABEEN RAZA ALI 3110205697908 16 27664597 Maded Ali Muhammad Boota 3530223352053 17 27664664 Muhammad Imran MUHAMMAD ANWAR 3520223937489 -

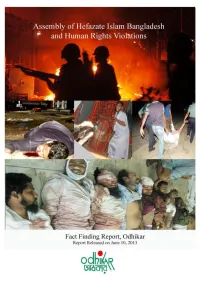

Odhikar's Fact Finding Report/5 and 6 May 2013/Hefazate Islam, Motijheel

Odhikar’s Fact Finding Report/5 and 6 May 2013/Hefazate Islam, Motijheel/Page-1 Summary of the incident Hefazate Islam Bangladesh, like any other non-political social and cultural organisation, claims to be a people’s platform to articulate the concerns of religious issues. According to the organisation, its aims are to take into consideration socio-economic, cultural, religious and political matters that affect values and practices of Islam. Moreover, protecting the rights of the Muslim people and promoting social dialogue to dispel prejudices that affect community harmony and relations are also their objectives. Instigated by some bloggers and activists that mobilised at the Shahbag movement, the organisation, since 19th February 2013, has been protesting against the vulgar, humiliating, insulting and provocative remarks in the social media sites and blogs against Islam, Allah and his Prophet Hazrat Mohammad (pbuh). In some cases the Prophet was portrayed as a pornographic character, which infuriated the people of all walks of life. There was a directive from the High Court to the government to take measures to prevent such blogs and defamatory comments, that not only provoke religious intolerance but jeopardise public order. This is an obligation of the government under Article 39 of the Constitution. Unfortunately the Government took no action on this. As a response to the Government’s inactions and its tacit support to the bloggers, Hefazate Islam came up with an elaborate 13 point demand and assembled peacefully to articulate their cause on 6th April 2013. Since then they have organised a series of meetings in different districts, peacefully and without any violence, despite provocations from the law enforcement agencies and armed Awami League activists. -

Prophet of Islam • Adam Was Created on Juma Day

1 | P a g e A Humble Request I have done my utmost to reproduce maximum number of Questions. To collect them and solve them with accuracy was a difficult task.i have tried my best to do it. However mistakes and erreors may be crept into. I humbly request to the reader of this Soft book to inform me each and every mistake and error they find in this SoftBook. Their cooperation will help me to produce next error free edition of this book. Amshid Ali (BS chemistry) 03122245270 Kohat University, KPK 2 | P a g e 3 | P a g e CONTENTS No Chapter page no 1. Islamiat 5 2. Pak Study 75 3. Geography of Pakistan 136 4. Basic Facts 150 5. History 166 6. General knowledge 175 7. Every Science 301 8. Important MCQs from solved Paper 347 4 | P a g e 5 | P a g e Islam Istalam is kissing of Hajr Aswad. Islam has 2 major sects. There are 5 fundaments of Islam. 2 types of faith. 5 Articles of faith. Tehlil means the recitation of Kalima. Deen-e-Hanif is an old name of Islam. First institution of Islam is Suffah. Haq Mahar in Islam is fixed only 400 misqal. Ijma means ageing upon any subject. Qayas means reasoning by analogy. There are four schools of thought of Islamic Law. Janatul Baki is situated in Madina. Masjid-e-Hanif is located in Mina. JANAT UL MOALA is a graveyard in MECCA. Qazaf: false accusation of adultery punishable with 80 lashes. Lyla-tul-Barrah means the Night of Forgiveness. -

A Matter of Comparison: the Holocaust, Genocides and Crimes Against Humanity an Analysis and Overview of Comparative Literature and Programs

O C A U H O L S T L E A C N O N I T A A I N R L E T L N I A R E E M C E M B R A N A Matter Of Comparison: The Holocaust, Genocides and Crimes Against Humanity An Analysis And Overview Of Comparative Literature and Programs Koen Kluessien & Carse Ramos December 2018 International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance A Matter of Comparison About the IHRA The International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) is an intergovernmental body whose purpose is to place political and social leaders’ support behind the need for Holocaust education, remembrance and research both nationally and internationally. The IHRA (formerly the Task Force for International Cooperation on Holocaust Education, Remembrance and Research, or ITF) was initiated in 1998 by former Swedish Prime Minister Göran Persson. Persson decided to establish an international organisation that would expand Holocaust education worldwide, and asked former president Bill Clinton and former British prime minister Tony Blair to join him in this effort. Persson also developed the idea of an international forum of governments interested in discussing Holocaust education, which took place in Stockholm between 27–29 January 2000. The Forum was attended by the representatives of 46 governments including; 23 Heads of State or Prime Ministers and 14 Deputy Prime Ministers or Ministers. The Declaration of the Stockholm International Forum on the Holocaust was the outcome of the Forum’s deliberations and is the foundation of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance. The IHRA currently has 31 Member Countries, 10 Observer Countries and seven Permanent International Partners. -

American Diplomacy Project: a US Diplomatic Service for the 21St

AMERICAN DIPLOMACY PROJECT A U.S. Diplomatic Service for the 21st Century Ambassador Nicholas Burns Ambassador Marc Grossman Ambassador Marcie Ries REPORT NOVEMBER 2020 American Diplomacy Project: A U.S. Diplomatic Service for the 21st Century Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs Harvard Kennedy School 79 JFK Street Cambridge, MA 02138 www.belfercenter.org Statements and views expressed in this report are solely those of the authors and do not imply endorsement by Harvard University, Harvard Kennedy School, or the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Design and layout by Auge+Gray+Drake Collective Works Copyright 2020, President and Fellows of Harvard College Printed in the United States of America FULL PROJECT NAME American Diplomacy Project A U.S. Diplomatic Service for the 21st Century Ambassador Nicholas Burns Ambassador Marc Grossman Ambassador Marcie Ries REPORT NOVEMBER 2020 Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs | Harvard Kennedy School i ii American Diplomacy Project: A U.S. Diplomatic Service for the 21st Century Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................3 10 Actions to Reimagine American Diplomacy and Reinvent the Foreign Service ........................................................5 Action 1 Redefine the Mission and Mandate of the U.S. Foreign Service ...................................................10 Action 2 Revise the Foreign Service Act ................................. 16 Action 3 Change the Culture .................................................. -

Conceptualising Historical Crimes

Should crimes committed in the course of Conceptualising history that are comparable to genocide, crimes against humanity or war crimes be Historical Crimes referred to as such, whatever the label used at the time?180 This is the question I want to examine below. Let us compare the prob- lems of labelling historical crimes with his- torical and recent concepts, respectively.181 Historical concepts for historical crimes “Historical concepts” are terms used to de- scribe practices by the contemporaries of these practices. Scholars can defend the use of historical concepts with the argu- ment that many practices deemed inadmis- sible today (such as slavery, human sacri- fice, heritage destruction, racism, censor- ship, etc.) were accepted as rather normal and sometimes even as morally and legally right in some periods of the past. Arguably, then, it would be unfaithful to the sources, misleading and even anachronistic to use Antoon De Baets the present, accusatory labels to describe University of Groningen them. This would mean, for example, that one should not call the crimes committed during the Crusades crimes against hu- manity (even if a present observer would have good reason to qualify some of these crimes as such), for such a concept was nonexistent at the time. A radical variant of the latter is the view that not only recent la- bels should be avoided but even any moral judgments of past crimes. This argument, however, can be coun- tered with several objections. First, diverg- ing judgments. It is well known that parties V HISTOREIN OLU M E 11 (2011) involved in violent conflicts label these conflicts differently. -

Birth of Bangladesh: Down Memory Lane

Indian Foreign Affairs Journal Vol. 4, No. 3, July - September, 2009, 102-117 ORAL HISTORY Birth of Bangladesh: Down Memory Lane Arundhati Ghose, often acclaimed for espousing wittily India’s nuclear non- proliferation policy, narrates the events associated with an assignment during her early diplomatic career that culminated in the birth of a nation – Bangladesh. Indian Foreign Affairs Journal (IFAJ): Thank you, Ambassador, for agreeing to share your involvement and experiences on such an important event of world history. How do you view the entire episode, which is almost four decades old now? Arundhati Ghose (AG): It was a long time ago, and my memory of that time is a patchwork of incidents and impressions. In my recollection, it was like a wave. There was a lot of popular support in India for Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his fight for the rights of the Bengalis of East Pakistan, fund-raising and so on. It was also a difficult period. The territory of what is now Bangladesh, was undergoing a kind of partition for the third time: the partition of Bengal in 1905, the partition of British India into India and Pakistan and now the partition of Pakistan. Though there are some writings on the last event, I feel that not enough research has been done in India on that. IFAJ: From India’s point of view, would you attribute the successful outcome of this event mainly to the military campaign or to diplomacy, or to the insights of the political leadership? AG: I would say it was all of these. -

Twir January 21-Feb 13.Pmd

January 21-February 3, 20, (4 & 5), 2013 Editor: Sanjeev Kumar Shrivastav Contributors Gulbin Sultana Sri Lanka, Maldives, Bangladesh Gunajn Singh China Mahtab Alam Rizvi Iran Princy Marine George Syria, Israel, Palestine, Turkey Prashant Pradhan Yemen Amit Kumar Defence Review Shristi Pukhrem Internal Security Review Keerthi Kumar UN Review Review Adviser: S. Kalyanaraman Follow IDSA Facebook Twitter 1, Development Enclave, Rao Tula Ram Marg, New Delhi-110010 Telephone: 91-26717983; Fax: 91-11-26154191 Website: www.idsa.in; Email: [email protected] The Week in Review January 21-February 3, 20, (4 & 5), 2013 CONTENTS In This Issue Page I. COUNTRY REVIEWS A. South Asia 2-8 B. East Asia 8-9 C. West Asia 9-12 II. DEFENCE REVIEW 12-15 III. INTERNAL SECURITY REVIEW 15-20 IV. UN REVIEW 21-22 1 The Week in Review January 21-February 3, 20, (4 & 5), 2013 I. COUNTRY REVIEWS A. South Asia Afghanistan Jan 21-27 l Kunduz Anti terror chief killed by suicide bomber According to reports, a suicide bomber has killed several Afghan officials and civilians in a crowded area of the northeast city of Kunduz, including “the city’s counter terrorism police chief and head of traffic police chief”, the Kunduz provincial governor’s spokesman Enayatullah Khaleeq said.1 Jan 28-Feb 3 l Afghan Defence Minister visits Pakistan; Pakistan’ offer to train Afghan forces being considered According to reports, Afghan Defence Minister Bismillah Khan Mohammadi arrived in Islamabad on January 27, commencing a five-day official trip. Leading a six-member delegation, Mohammadi will begin talks with Pakistan’s civil and military authorities on Monday, including Chief of Army Staff General Ashfaq Parvez Kayani. -

Sasha Paul Final Thesis

PAKISTAN AGAINST ITSELF: THE RISE OF EXTREMISM By Sasha J Paul Bachelor of Arts, Dalhousie University, 1997 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Arts in the Graduate Academic Unit of History Supervisor: David Charters, PhD, Department of History Examining Board: Gary Waite, PhD, Acting Director of Graduate Studies, Chair J. Marc Milner, PhD, Department of History Lawrence Wisniewski, PhD, Department of Sociology This thesis is accepted by the Dean of Graduate Studies THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW BRUNSWICK April 2014 ©Sasha J Paul, 2014 ABSTRACT An analysis of Pakistan’s political, social, institutional and regional history reveals two principal problems facing the state: first, the enmity that developed between Pakistan and India following partition, has morphed into an overwhelming national obsession with India which has supported unbridled growth of Pakistan’s security institutions at the expense of Pakistan’s ability to govern its own people. Second, despite the lofty aims of Mohammad Ali Jinnah to build his country into a modern democratic and secular state, the confluence of certain key factors have prevented Pakistan from ever moving towards this ideal. This study will examine the complex web of factors that have spawned Pakistan’s current situation as a failing nuclear state such as: the outstanding grievances from the partition of colonial India and subsequent conflicts, support of the Mujahedeen in Afghanistan and the social, institutional, and economic domestic factors. Pakistan’s overt and tacit support of extremists is a double-edged sword that undermines at any semblance of stability for this country as it grapples with a growing number of suicide attacks, targeted killings, kidnappings, increased criminal activity and rising drug addiction, yet the status quo continues with little expectation of positive change. -

In East Pakistan (1947-71)

Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bangladesh (Hum.), Vol. 63(1), 2018, pp. 59-89 THE INVISIBLE REFUGEES: MUSLIM ‘RETURNEES’ IN EAST PAKISTAN (1947-71) Anindita Ghoshal* Abstract Partition of India displaced huge population in newly created two states who sought refuge in the state where their co - religionists were in a majority. Although much has been written about the Hindu refugees to India, very less is known about the Muslim refugees to Pakistan. This article is about the Muslim ‘returnees’ and their struggle to settle in East Pakistan, the hazards and discriminations they faced and policy of the new state of Pakistan in accommodating them. It shows how the dream of homecoming turned into disillusionment for them. By incorporating diverse source materials, this article investigates how, despite belonging to the same religion, the returnee refugees had confronted issues of differences on the basis of language, culture and region in a country, which was established on the basis of one Islamic identity. It discusses the process in which from a space that displaced huge Hindu population soon emerged as a ‘gradual refugee absorbent space’. It studies new policies for the rehabilitation of the refugees, regulations and laws that were passed, the emergence of the concept of enemy property and the grabbing spree of property left behind by Hindu migrants. Lastly, it discusses the politics over the so- called Muhajirs and their final fate, which has not been settled even after seventy years of Partition. This article intends to argue that the identity of the refugees was thus ‘multi-layered’ even in case of the Muslim returnees, and interrogates the general perception of refugees as a ‘monolithic community’ in South Asia. -

Merchant/Company Name

Merchant/Company Name Zone Name Outlet Address A R LADIES FASHION HOUSE Adabor Shamoli Square Shopping Mall Level#3,Shop No#341, ,Dhaka-1207 ADIL GENERAL STORE Adabor HOUSE# 5 ROAD # 4,, SHEKHERTEK, MOHAMMADPUR, DHAKA-1207 Archies Adabor Shop no:142,Ground Floor,Japan city Garden,Tokyo square,, Mohammadpur,Dhaka-1207. Archies Gallery Adabor TOKYO SQUARE JAPAN GARDEN CITY, SHOP#155 (GROUND FLOOR) TAJ MAHAL ROAD,RING ROAD, MOHAMMADPUR DHAKA-1207 Asma & Zara Toy Shop Adabor TOKIYO SQUARE, JAPAN GARDEN CITY, LEVEL-1, SHOP-148 BAG GALLARY Adabor SHOP# 427, LEVEL # 4, TOKYO SQUARE SHOPPING MALL, JAPAN GARDEN CITY, BARCODE Adabor HOUSE- 82, ROAD- 3, MOHAMMADPUR HOUSING SOCIETY, MOHAMMADPUR, DHAKA-1207 BARCODE Adabor SHOP-51, 1ST FLOOR, SHIMANTO SHOMVAR, DHANMONDI, DHAKA-1205 BISMILLAH TRADING CORPORATION Adabor SHOP#312-313(2ND FLOOR),SHYAMOLI SQUARE, MIRPUR ROAD,DHAKA-1207. Black & White Adabor 34/1, HAZI DIL MOHAMMAD AVENUE, DHAKA UDDAN, MOHAMMADPUR, DHAKA-1207 Black & White Adabor 32/1, HAZI DIL MOHAMMAD AVENUE, DHAKA UDDAN, MOHAMMADPUR, DHAKA-1207 Black & White Adabor HOUSE-41, ROAD-2, BLOCK-B, DHAKA UDDAN, MOHAMMADPUR, DHAKA-1207 BR.GR KLUB Adabor 15/10, TAJMAHAL ROAD, MOHAMMADPUR, DHAKA-1207 BR.GR KLUB Adabor EST-02, BAFWAA SHOPPING COMPLEX, BAF SHAHEEN COLLEGE, MOHAKHALI BR.GR KLUB Adabor SHOP-08, URBAN VOID, KA-9/1,. BASHUNDHARA ROAD BR.GR KLUB Adabor SHOP-33, BLOCK-C, LEVEL-08, BASHUNDHARA CITY SHOPPING COMPLEX CASUAL PARK Adabor SHOP NO # 280/281,BLOCK # C LEVEL- 2 SHAYMOLI SQUARE COSMETICS WORLD Adabor TOKYO SQUARE,SHOP#139(G,FLOOR)JAPAN GARDEN CITY,24/A,TAJMOHOL ROAD(RING ROAD), BLOCK#C, MOHAMMADPUR, DHAKA-1207 DAZZLE Adabor SHOP#532, LEVEL-5, TOKYO SQUARE SHOPPING COMPLEX, JAPAN GARDEN CITY (RING ROAD) MOHAMMADPUR, DHAKA-1207.